It seems that the fortunes of the cotton crop are turning this year. After posting record-low output in the previous year farmers and ginners are expecting a bumper crop. And on top of that, the commodities market outlook for cotton is looking up after the government assured farmers that a support price of Rs 8500 per maund (around 40 KG).

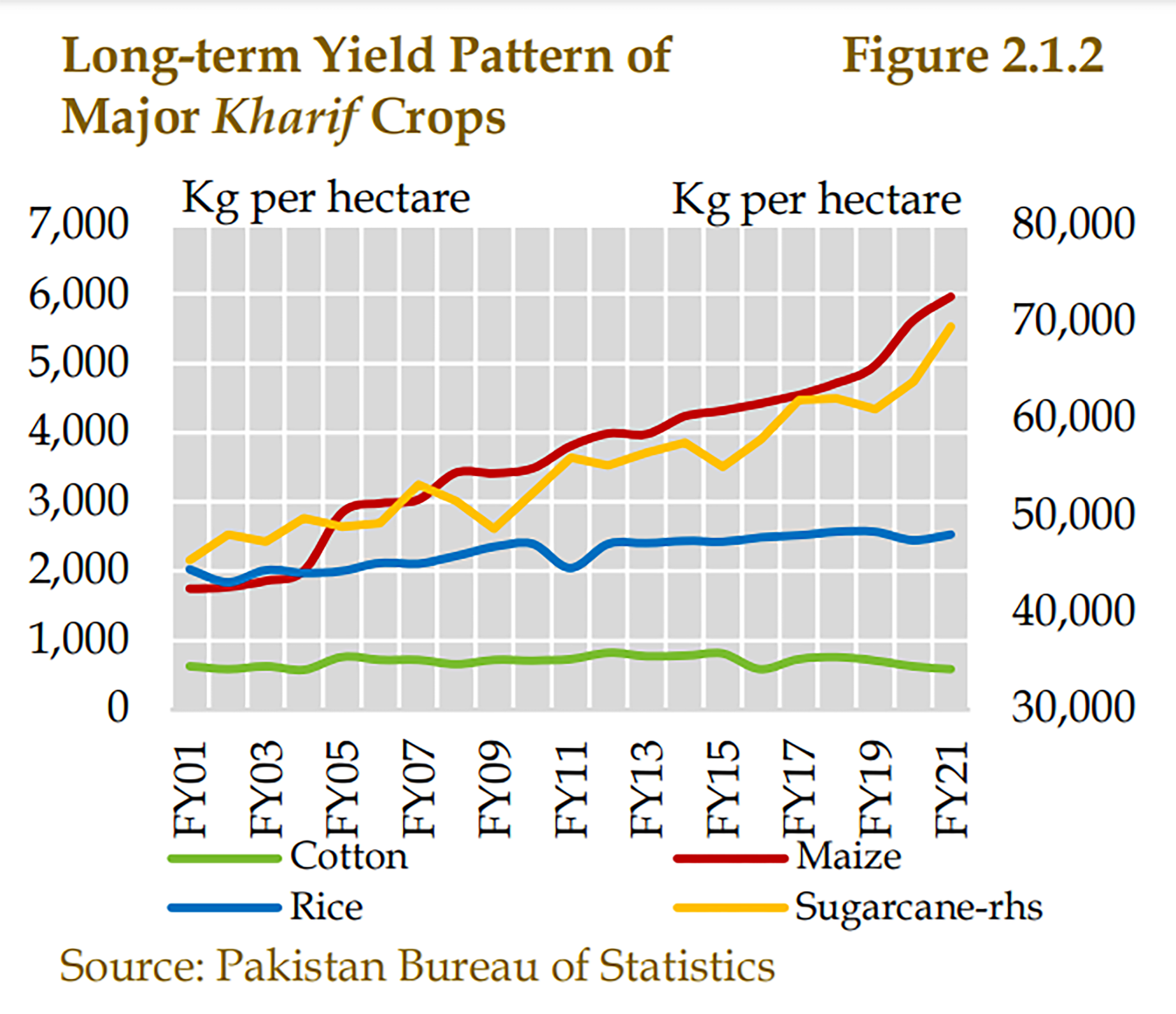

This marks a serious turn in luck for white lint which for the past two decades has been taking blow after blow. But why exactly is cotton’s future bright? Over the years the crop has only made way for more profitable cash crops such as sugarcane. Farmers have abandoned it in droves because cotton seeds in Pakistan are largely uncompetitive compared to cotton producing countries in the rest of the world. And because of these weak and inefficient seeds that have not seen any genetic modification since 2005, the cotton crop is also very susceptible to disease and climate change — two linked factors that have wiped out entire farms over the years.

The reason behind the better outlook this year is that early in August, the Trading Corporation of Pakistan (TCP) entered the cotton market to stabilize the white lint prices. TCP announced it would purchase one million bales of lint to stabilize the market so that the growers may get the minimum rate of Rs8,500 per maund as promised by the government at the outset of the sowing season to woo the farmers back to the crop.

And that is where the problem starts and the problem ends. The government had promised a support price to cotton growers and TCP had to step in when the value of harvested cotton fell below that support price. Since then, there have been some developments on the agricultural front that have also bolstered cotton. However, this is another example of a temporary upwards blip that took place circumstantially. Once the pride of Southern Punjab and Sindh, the once thriving Kapas belt of the country is now left to relive its glory days through anomalies such as this year. But how did we get here?

This year’s situation

This is what happened this year. For some time now, Pakistan’s local textile industry has been relying on imported cotton. This is a bit counterintuitive since textiles is the country’s largest export oriented sector. So for the sector to first import its raw materials, then process them and export them dents bottom-lines. In comparison, if Pakistani cotton was up to the mark then there would be a situation where profit margins would be much higher.

The relationship between cotton and the textile industry has often been tumultuous, and this year was also another example of that. Up until around 2008 cotton was a major cash-crop in Pakistan. In fact, in 2005, cotton became one of the only crops in Pakistan for which GMO seeds were introduced. According to a 2021 report of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), raw cotton consumption grew at an annual growth rate of 7% between 1982 and 2008 to reach 15.6 million bales in 2007-08 in Pakistan.

This was largely because cotton ginners would buy raw cotton and provide it to the textile mills which were always hungry for more. However, between 2007-08 Pakistan was hit by the global recession. The textile industry faced challenges due to high energy costs, rupee depreciation vis-à-vis the US $ and other currencies, and a high cost of doing business. As a result, there was a reduction in the number of textile mills operating in the country from about 450 units in 2009 to 400 units in 2019. This decrease has simultaneously seen the domestic demand for cotton dip in the country.

Farmers and the textile industry, up until the 2008 financial crisis, had been dependent on each other. Farmers would produce the crop without the fear that demand would fall, and the government did not need to announce a support price either. But when mills started shutting down, suddenly there was more cotton and not enough buyers. After a harsh couple of years, farmers also began going back on cotton and its price fell, resulting in production decreasing. As a result, exports were also affected.

Two decades ago, Pakistan’s cotton was in demand globally. However over those 20 years, countries such as Bangladesh, Vietnam and Cambodia have all used better growing techniques to get ahead of Pakistan. In 2003, when Pakistan’s textile exports were $8.3 billion, Vietnam’s textile exports were $3.87 billion, Bangladesh’s were at $5.5 billion. Now Vietnam is at $36.68 billion and Bangladesh is at $40.96 billion, while Pakistan is struggling to hit $25.3 billion in 2020.

So what happened this year? Essentially, the United States was hit with a low production year. Cotton production in the US in 2022-23 is forecast to fall by 3.7 million bales from the previous marketing year (MY) to 13.8 million bales, the lowest production level in seven years. This will result in US cotton exports for MY 2022-23 to fall at 12.5 million bales, down by 100,000 bales from the previous month’s forecast and 14 per cent lower than MY 2021-22, according to the US department of agriculture (USDA).

US Cotton was facing the same issues as Pakistan — high temperatures and drought in Texas, where 40 percent of US cotton production occurs, have slashed production and exportable supplies. As a result global trade is down by nearly a million bales from the previous month’s forecast.

The perfect storm

It is a case of things falling exactly in place. On the one hand US expected output fell significantly. Overall cotton prices improved in the domestic market as textile millers and spinners showed their interest in buying during the last week, while the quality of lint reaching ginning factories also got relatively better due to the end of rains in the cotton belt resulting in reduced moisture in phutti (raw cotton). The buying interest was reinforced by reports that the TCP had prepared a strategy to purchase one million bales and had appointed agents in various cotton districts for the purpose.

In Sindh, the price of lint was reported between Rs17,800 and Rs18,200 per 40kg, and of phutti was Rs7,800 to Rs8,300; in Punjab Rs17,900-Rs18,500 and Rs7,600-Rs9,000; in Balochistan, the price of cotton ranged between Rs17,800 and Rs17,900 and of phutti between Rs7,700 and Rs8,300. The committee of the Karachi Cotton Association increased the spot rate by Rs200 per 40kg to Rs18,235.

Karachi Cotton Brokers Forum chairman Naseem Usman says that cotton prices in the international market have increased on reports that the US cotton production will remain about 2.5 million bales less than the estimates. The New York cotton futures rate stood at 87.89 US cents per pound.

On top of this Pakistan also saw a great agricultural boon. In a good omen to crop output in both current and next cropping season, the country’s two major reservoirs — Tarbela and Mangla — rose to full capacity for the first time in years. Originally, it had been projected that there would be a serious shortage of water in the country. The Kharif season had started in April with 37pc anticipated water shortage with 27pc shortage in early Kharif and about 10pc in late Kharif.

In a stroke of good fortune, the Eastern rivers — Ravi, Beas and Sutlej — flowed with sufficient waters after a gap of more than a decade. Enough water is now available in the system downstream of these rivers, reducing the need for discharges from Mangla dam. The Indian reservoirs on Sutlej and Beas are now again nearing maximum levels at Bhakra and Pong storages.

Earlier this month the government announced that or the first time in over half-a-decade history, the country’s three reservoirs — Mangla, Tarbela dams and Chashma Barrage — attained their maximum capacity on a single day putting total water storage at the highest 13.443 million acre-feet. This has raised hopes for a bumper crop in the coming year according to officials of the Indus River System Authority (Irsa).

The larger problem

Of course this does not solve the larger issue. Years when things fall in place will come and go. A year ago 2022 had proven good for cotton growers as well. Back then the cotton crop that was sown in Pakistan in 2021 and was harvested in 2022 benefited from a peculiarity of international trade caused by Covid-19 that resulted in a bumper crop of cotton.

When the pandemic hit, everything changed and the local industry found that importing cotton was no longer an option. International cotton prices (in rupee terms) during the last year have gone up by almost 30% — from PKR 12,606 on July 1, 2021, to PKR 18,259 by mid-February this year. The ever-dwindling value of the rupee not only doubled the impact of import for Pakistani millers but also made it next to impossible to calculate the final cost of production, rendering import commercially non-feasible for the industry.

On top of this, there were shipping concerns. A report in Dawn from March 2022 chronicled how it takes more than 120 days to ship cotton to Pakistan these days, against the 30-day hiatus in pre-Covid times. These circumstances deflated the textile industry’s claim that it could thrive, even survive, on imported cotton and forced it to value local crops, thus setting the stage for the cotton revival in the country.

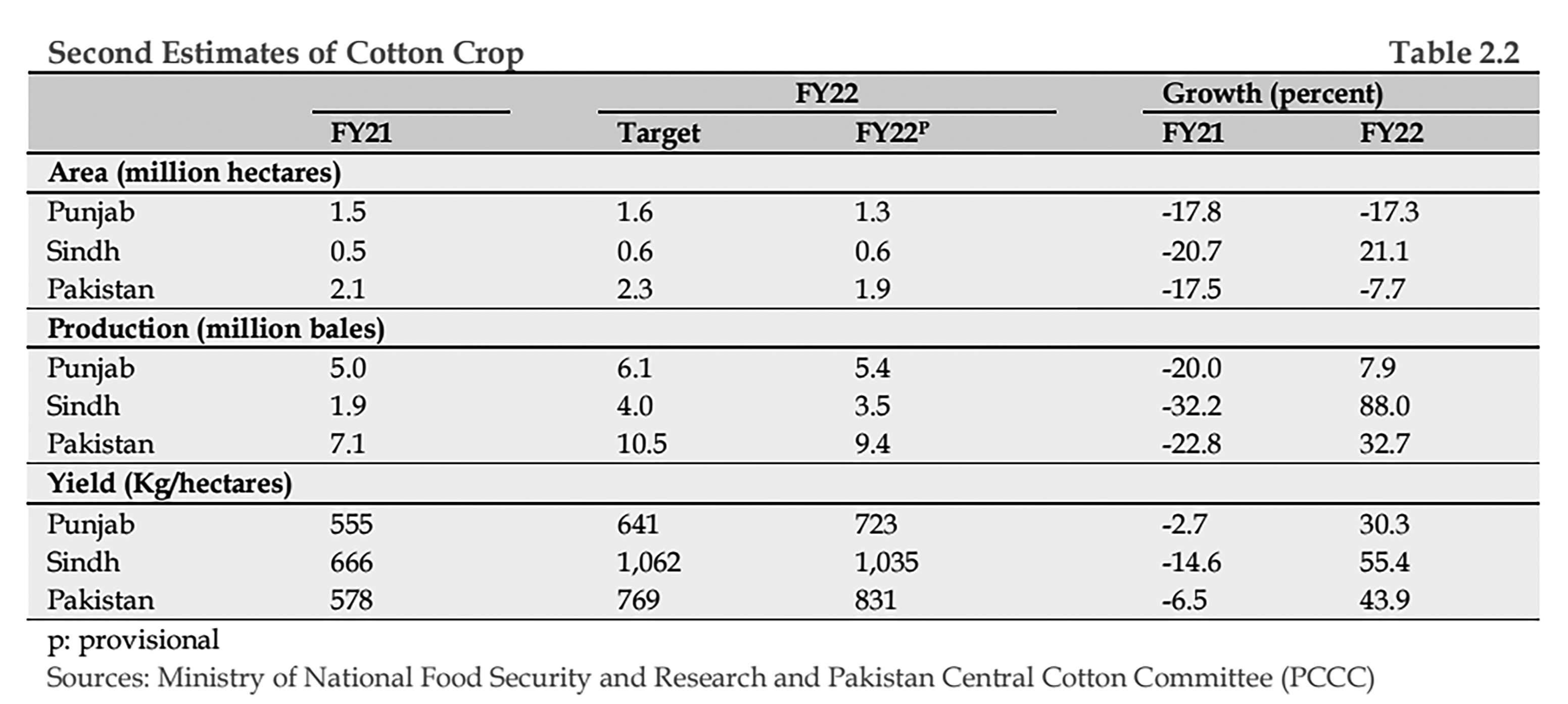

Similarly this year it was the falling fortunes of US cotton that helped Pakistan’s cotton growers. The reality is that cotton has overall seen a serious decline in the country. The story of cotton in Pakistan has been that of an opportunity squandered. Between 2005 and 2020, Pakistan’s production of cotton declined by nearly 35%, from nearly 14 million bales in 2005 to just over 9 million bales in 2020.It further fell to 5.6 million bales in 2021, before making a brief recovery at 7.7 million bales in 2022, and has now fallen to a paltry 4.9 million bales in 2023. This marks an overall decline of 65% in the past 18 years.

The data speaks for itself. Zoom in to cotton production over the past few years and it is a sordid tale. As recently as 2017, Pakistan’s cotton production was high, clocking in at over 10 million bales for the year. The output actually rose by a million bales to 11 million in 2018, before settling again at just over 9 million bales in 2019. The next two years saw a decline. In 2020, only 8 million bales were recorded before a sharp fall to 5.6 million bales in 2021.

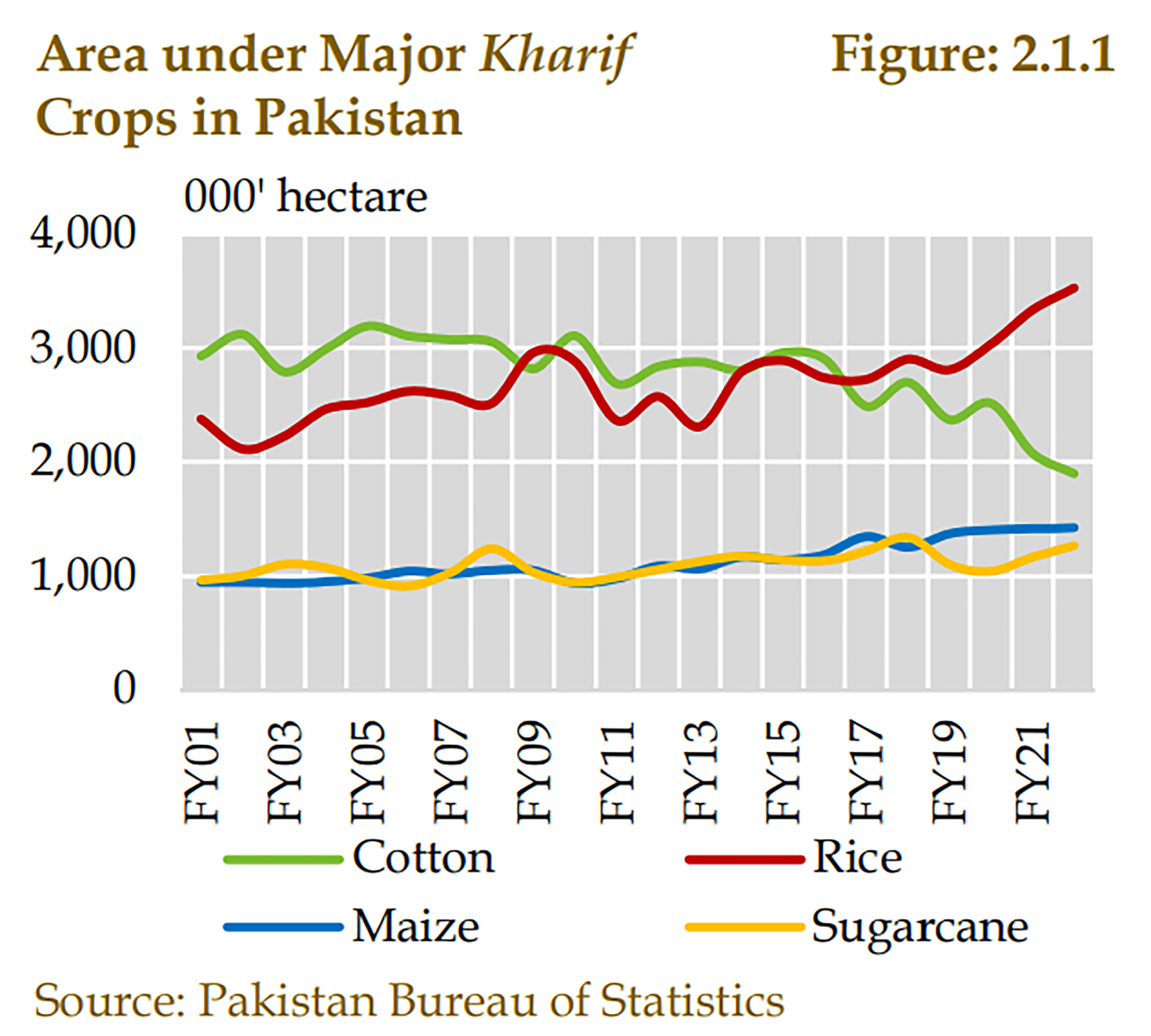

Farmers over the past decade have abandoned cotton in favour of more profitable crops like sugarcane. In 1991, cotton was grown on around 6.6 million acres of land all over Pakistan. It grew to a peak area-under-cultivation level of 7.9 million acres in 2005 but stood at a mere 6.2 million in 2020 showing a serious downward trajectory. Changing climatic conditions have made the cotton seed in Pakistan less resistant and more likely to fail — which means growing it has become a bad business decision for a number of agriculturalists.

As the core issues of the cotton crop remain unaddressed, farmers will continue to abandon this crop and instead grow richer products such as sugarcane which are short term cash crops but bad for agriculture and the climate in the long-run.