A leading print media outlet recently reported that negotiations between Pakistan and Chinese banks – Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) and Bank of China for a $600 million loan – faced a setback due to new conditions, linking the loan disbursements to the resolution of Pakistan’s debt to Chinese Independent Power Plants (IPP).

As per the reports, these conditions were rejected by the government due to budget concerns and the risk of setting a precedent. However, Chinese officials asserted that the condition of the settlement of Chinese IPP debts is inaccurate and that they are actively collaborating with Pakistani counterparts to resolve the issue.

While speaking to Profit, Dr Ammar A. Malik, senior research scientist at AidData, commented, “This is probably the first time in the history of CPEC that the Chinese are putting this sort of pressure on Pakistan. Of course, the Chinese have denied and said that they are trying to resolve the situation but it looks like the government’s ministry of finance has clearly said that they feel that the Chinese are putting conditions.”

While this situation is unprecedented, are we really surprised?

IPP policy of Pakistan

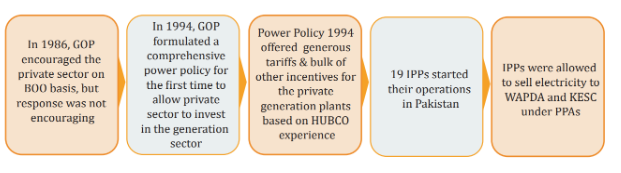

In the early 1990s, Pakistan faced severe electricity shortages due to administrative negligence towards power sector infrastructure. This imbalance between demand and supply resulted in unprecedented electricity outages, creating a crisis for domestic and industrial consumers. Consequently, Pakistan introduced a new power policy in 1994 to address the situation.

Source: Power Sector – An Enigma with No Easy Solution

These policies attracted foreign investment, in other words, independent power producers (IPPs). To incentivise IPPs, a capacity charge was introduced, which covered debt servicing, operation costs, insurance expenses, and the return on equity. Energy price was added on top of it based on energy sold. The government bought electricity from IPPs by paying a power purchase price.

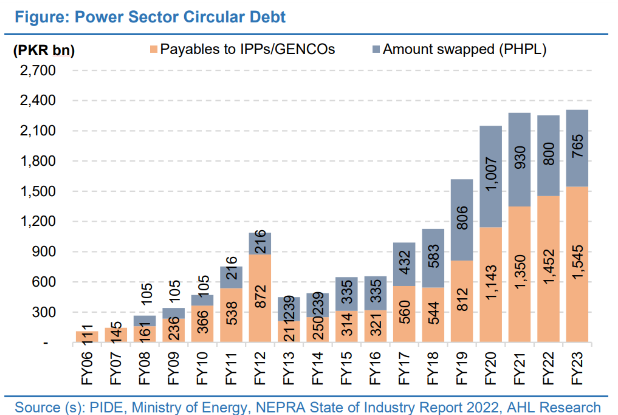

The capacity charge, high tariff offered to IPPs, no incentive for cost reduction and inefficiencies added to the circular debt predicament.

Circular debt is the payment withheld by the Central Power Purchasing Agency (CPPA) due to cash flow deficit leading to cash flow problems for other players in the supply chain.

The main causes of circular debt according to the Arif Habib Pakistan Strategy 2024 report are: “Inadequate sector governance, Delays in tariff determination and notification, Lag in fuel price adjustments, Insufficient revenue recovery from both government and private consumers, High Transmission and Distribution (T&D) losses.”

Poor collections revenue collection of power distribution companies (DISCOs) from private and government customers along with delayed and incomplete tariff differential subsidies (TDS) payment by the government to DISCOs and K-Electric adds to the shortfall in inflows.

This sets in motion a series of outstanding receivables in the books of multiple companies in the supply chain including fuel suppliers, generation companies and transmission companies.

Chinese investment in Pakistan

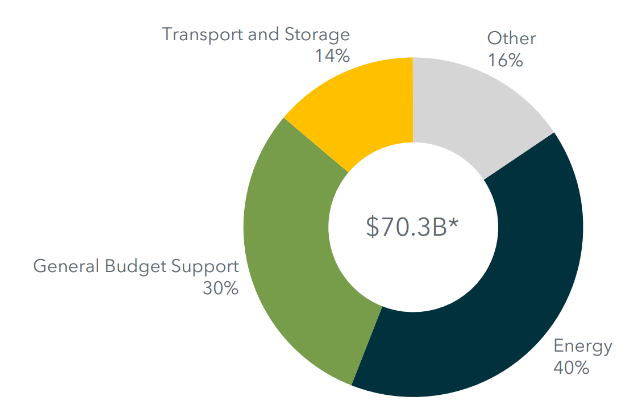

As per data released by AidData, China’s development finance committed to Pakistan between 2000 and 2021 valued at $70.3 billion, out of which 98% was in the form of loans while grants made up for remaining 2%. Of this financing, 8% was official development assistance (grants and highly concessional loans) and 89% was other official sector loans. The average interest rate on loans is 3.72% with 9.84 years maturity and 3.74 years grace period which means a portion of these loans has entered the repayment phase.

In terms of sectoral distribution, the energy sector saw a lion’s share at 40%, amounting to $28.4 billion. A large chunk of it came under the CPEC initiative post 2014. “Currently there are 14 energy projects operational under CPEC which include transmission projects as well as IPPs. There also exists a pipeline of upcoming projects,” remarked Basit Ghauri, an energy markets professional at a think tank in Islamabad.

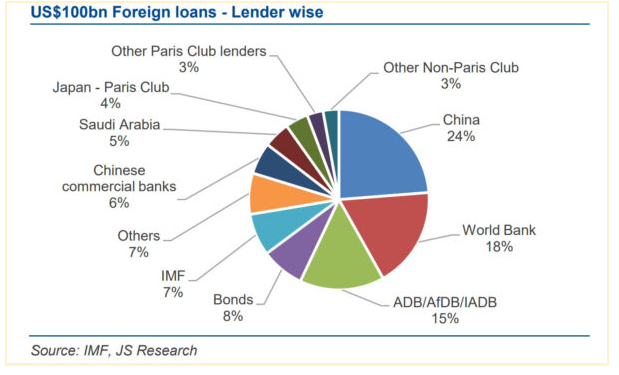

These investments have also elevated China’s position on Pakistan’s debt table, as the country holds around 30% of Pakistan’s external public debt.

China’s shifting its strategy

Beijing is currently grappling with a domestic banking crisis of its own. As AidData’s recent findings, China is faced with the challenge of navigating an unfamiliar and uncomfortable role as the world’s largest official debt collector. Around 55% of its loans to low-and middle-income countries have already entered their principal repayment periods, and this percentage is projected to increase to 75% by 2030.

Additionally, Beijing is finding its footing as an international debt collector at a time when many of its biggest borrowers are illiquid or insolvent. This situation exposes Chinese state-owned policy banks, commercial banks, and enterprises to the risk of default from overseas borrowers.

In December 2023, Moody downgraded its outlook on China’s government credit ratings to negative from stable. Similarly, it downgraded eight Chinese banks from stable to negative. The lenders that were downgraded included the big four Chinese lenders: ICBC, Agricultural Bank of China, Bank of China and China Construction Bank Corporation.

Moody’s linked the downgrade of these banks to a decline in the central government’s rating. Moody’s downgrade reflects concerns over rising debt levels and the impact on broader growth as Beijing resorts to fiscal stimulus to support local governments and contain the spiralling debt crisis.

How circular debt affects Chinese IPPs and banks

The circular debt pertaining to Chinese IPPs has crossed the Rs 400 billion mark, leaving these companies with a severe liquidity problem.

Large infrastructure projects like those in the energy sector usually require substantial financing. “Debt to equity ratio is typically 80:20 or 75:25 for all IPPs,” said Ghauri. This means that IPPs’ 75-80% of capital is funded through loans, and in the case of Chinese IPPs, these loans are from Chinese banks like ICBC and Bank of China. For example, let’s look at the case of Huaneng Shandong Ruyi (Pakistan) Energy (Pvt.) Limited (HSR), a Chinese IPP built under CPEC has established the Sahiwal Coal Power Project. According to a PACRA credit rating report, debt financing constitutes 80% of the project cost which was funded by the Chinese lenders with the consortium led by ICBC and others including Agriculture Bank of China Ltd., China Construction Bank., and Bank of China Ltd.

When receivables are delayed, due to circular debt, IPPs struggle with cash flows to make payments back to the primary lender across the border in China.

Coming back to HSR’s example, as per the PACRA report, outstanding receivables from CPPA increased to Rs 111 billion by June 2023 which has created liquidity concerns for the IPP. “The delays in payments from CPPAG have created liquidity concerns for IPPs. To bridge the working capital gap, as of June 2023, the Company has availed 100% short-term borrowing lines of Rs 49.5 billion to fund its working capital needs,” read the PACRA report.

Why did the Chinese banks set forth such conditions?

Chinese banks’ unprecedented move in Pakistan, noted by Malik, departs from their historical sympathy and frequent bailouts. “But seems like at least these two banks are not in the mood to do that,” added Malik.

This shift reflects actions taken in Ethiopia where ICBC suspended about $67 million worth of disbursements and halted additional loan agreements in response to the government’s loan repayment default. “Bank of China and ICBC appear to now be taking a similar approach with Pakistan”, remarked Bradley C. Parks, executive director at AidData.

Park told Profit that Chinese state-owned policy banks and commercial banks work in concert – as “China, Inc.” – to maximize their leverage over a sovereign borrower to minimise default risk. They also include strategic clauses in lending contracts. “They also withhold the provision of new funds until borrowers honour their repayment obligations,” said Park.

Beijing’s conditions for providing additional balance of payments support (liquidity support loans), as explained by Parks, are linked to the repayment of overdue infrastructure project debts. The failure of a borrower like Pakistan to settle these debts, even after substantial balance of payments support, might have prompted Beijing to reconsider further financial assistance.

Malik emphasised the commercial orientation of these state-owned Chinese banks. “This means that they want their loans back on time.” He underscores the banks’ perception that since Pakistan owes them through the IPP energy projects, they perceive that this is not conducive to extending new loans.

“Furthermore, the current political uncertainty is likely influencing the banks’ decisions as banks like to have more political stability,” added Malik. Pakistan is currently being run by an interim government which is going to be around for less than a month now. Moreover, there is uncertainty around elections even though an election date has been announced.

While the imposed condition is unfavourable for a cash-strapped country, Malik reassures that, given the ongoing IMF program, this is not an existential problem as the IMF is responsible for making sure that the country stays afloat and takes the right decisions to fill its financing gaps.

Pakistan has jumped into American and gulf Arabian ship… nothing new