It has been one of the slowest election campaigns in Pakistan’s history. Major political parties did not begin mobilising their workers until a few weeks ago, and major national leaders have addressed a limited number of jalsas and rallies.

Election campaigns usually run for at least a couple of months. Leaders get to tour the country and spread their rhetoric and their opponents get to respond in turn. Battles are waged in the media and in shows of street strength. All of this takes not just effort but investment. And since Pakistan is a parliamentary democracy with 272 electable seats of the national assembly, there are 272 different campaigns taking place within the country during general elections.

In every constituency this massive economic activity is governed by rules and regulations of the Election Commission of Pakistan. The problem is that these regulations are outdated and completely ignored. The ECP says that the campaign spend for a national assembly seat is a maximum of Rs 1 crore while the limit is Rs 40 lakhs for a provincial constituency. The problem is that in many of these constituencies this amount is not even enough to cover transportation costs. In fact, on average, from getting a ticket to ending a campaign large NA campaigns have ended up spending up to Rs 15 crore on a single campaign this year.

So how do they get away with spending this much money? And what exactly are the expenditures of a campaign?

What is the maximum amount of money a candidate is allowed to spend on their election campaign?

Considering the impact of inflation, ECP has revised upwards the expenditure limits for electoral campaigns. This revision marks the seventh instance in the nation’s history where such an increase has been enacted. Now, a candidate contesting for a seat in the National Assembly is permitted to spend as much as Rs 1 crore, while a candidate for the Provincial Assembly is allowed a budget of up to Rs 40 lakhs. In addition, the Commission has introduced a stipulation requiring candidates to maintain a separate bank account specifically for their campaign expenditures. They are also obligated to keep and preserve all expenditure receipts, which must be available for presentation upon request.

A history of campaign financing regulations

Between 2018 and 2023, the average annual inflation rates in the country stood at 5%, 9.4%, 9%, 9.5%, 19.73%, and 33%, in that order. During the 2018 elections, the spending caps for candidates were determined based on the Election Act of 2017. This legislation permitted candidates for the National Assembly to spend a maximum of 4 million rupees, while those running for Provincial Assembly seats were allowed up to 2 million rupees. Reflecting changing economic conditions, the Election Commission has adjusted these campaign expenditure limits on six occasions across the past 10 general elections.

During the 1970 general elections for the National and Provincial Assemblies, the spending limits set by the National and Provincial Assemblies Election Ordinance 1970 allowed candidates to spend up to 25,000 rupees on National Assembly campaigns and 15,000 rupees on Provincial Assembly campaigns. This was an increase from the previous limits of 15,000 rupees for National Assembly and 10,000 rupees for Provincial Assembly candidates.

By the time of the 1977 elections, these limits were raised further: candidates for the National Assembly could spend up to 40,000 rupees, representing a 60% increase, and those for the Provincial Assembly could spend up to 25,000 rupees, a 66% increase. During the non-party elections in 1985, these revised spending limits were maintained.

For the 1988 general elections, the campaign expenditure caps experienced a dramatic increase of 1150%, setting the spending limit at 500,000 rupees for National Assembly candidates and 300,000 rupees for Provincial Assembly candidates. These limits were retained for the 1990 elections. In the 1993 elections, the expenditure limits were again adjusted, this time doubling the allowed spending. National Assembly candidates were permitted to spend up to 1 million rupees, while Provincial Assembly candidates could spend as much as 600,000 rupees.

During the 1997 elections, the Election Commission decided to retain the existing expenditure limits. However, in 2002, with the introduction of the Election Commission Ordinance 2002, these limits were revised upwards. For National Assembly candidates, the limit was increased by 50%, setting it at 1.5 million rupees, and for Provincial Assembly candidates, the limit was raised by 66% to 1 million rupees. These revised expenditure caps were then maintained through the 2013 elections.

In 2017, the Election Commission implemented the Election Act 2017, which significantly raised the campaign expenditure limits. The new regulation marked a 166% increase in the spending cap, allowing National Assembly candidates to allocate up to 4 million rupees for their campaigns, and Provincial Assembly candidates up to 2 million rupees.

Is this limit feasible for the candidates?

The response is unequivocally negative, particularly for candidates affiliated with major political parties. Unfortunately, even after Profit’s attempts to engage in discussions with various candidates, there was no clear consensus on the actual amount of money spent on election campaigns. A National Assembly candidate from the Pakistan Muslim League-N, representing a constituency in Lahore, conveyed to Profit that running and securing a victory in a National Assembly election typically requires a candidate to spend a minimum of 15 to 20 crore rupees. This amount makes the established spending cap of 1 crore rupees seem insignificant, comparable to a mere speck in the grand scheme of things.

The candidate detailed the financial requirements for contesting elections through a political party, explaining that the initial step involves submitting an application. The party evaluates the candidate’s popularity and other factors before deciding whether to issue a ticket. For instance, major political parties, such as the People’s Party, currently require a bank draft of 40,000 rupees for a National Assembly ticket and 30,000 rupees for a Provincial Assembly ticket along with the application. In Balochistan, an underdeveloped province, the Balochistan Awami Party (BAP) has set the application fee at 1.5 lakh rupees for National Assembly and 1 lakh rupees for Provincial Assembly candidates. Similarly, the Muslim League-N requires a fee of 2 lakh rupees for National Assembly tickets and 1 lakh rupees for Provincial Assembly tickets.

Believing that popularity in your constituency and the financial capability to contest are sufficient for securing a party ticket is a misconception. In reality, every hopeful candidate is expected to contribute a considerable sum as a donation to party officials. This unofficial ‘rate’ for securing a ticket varies across different constituencies, cities, and regions. While some individuals may obtain a ticket due to their political connections, this often comes with the responsibility of covering additional expenses imposed by the party.

Assuming a National Assembly candidate manages to obtain a ticket from a well-known political party, it is likely that the process would cost no less than 5 crore rupees. This is particularly true for parties that are popular and have a higher likelihood of winning. The cost for a ticket can vary significantly depending on the party, with fluctuating rates observed among parties like Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, Muslim League-N, and the People’s Party. Presently, it’s reported that even the ticket prices set by the Balochistan Awami Party (BAP) are exceptionally high.

While the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) has imposed a campaign expenditure cap of 1 crore rupees, candidates often incur expenses between 5 to 6 crore rupees even before the formal campaign begins. National Assembly constituencies cover extensive areas, leading to significant costs. Many individuals working within these constituencies are directly compensated by the candidate. Additional expenses include setting up campaign offices, conducting door-to-door canvassing, and creating visible campaign materials like flexes and banners. The expense of providing food at rallies, processions, and corner meetings can approach 1 crore rupees. In today’s digital age, substantial amounts are also spent on social media campaigns. Furthermore, some candidates engage in vote-buying, which adds to their expenses. On election day, candidates often bear the cost of transporting numerous voters to polling stations.

The candidate questions the practicality of the ECP’s spending limits, pointing out that adherence is rare. He suggests that campaign funds are often channeled through supporters and investors, allowing candidates to maintain a degree of separation from these expenditures. Considering the recent surge in inflation, the candidate estimates that a National Assembly campaign now requires a budget of at least 5 crore rupees. This estimate does not include the spending of independent candidates.

Reflecting on his own experience, the candidate disclosed that in the previous election, his expenditure was around 7 crore rupees. In the current campaign, he has already surpassed this figure, spending over 7 crore rupees, and anticipate that the total cost may reach up to 10 crore rupees.

The perspective of a Provincial Assembly ticket holder from Multan, belonging to a renowned political party, echoes a similar sentiment. This candidate notes that while the expenditure for contesting a Provincial Assembly election is marginally lower compared to a National Assembly election, it significantly exceeds the expenditure cap established by the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP).

The candidate highlighted that typical expenses such as obtaining party tickets, organizing rallies, holding corner meetings, producing printing materials, and covering transportation costs are well-known. Notably, in this election cycle, there has been a marked increase in using social media to promote electoral campaigns and party platforms. Social media has become a crucial tool for political parties to connect with the wider public. In preparation for the 2024 election, political parties and candidates are increasingly turning to social media, investing considerable sums in their online presence. However, the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) lacks a system to monitor and regulate the expenses incurred for social media campaigning. Major political and religious parties, including PML-N, PTI, PPP, Jamaat-e-Islami, JUI, MQM, and others, have developed dedicated social media divisions, allocating millions of rupees for digital campaigning and making extensive use of social media for election activities.

There are two primary strategies for conducting advertising campaigns on social media. The first involves sharing messages, videos, and images on platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube at no cost. The second strategy entails spending money to enhance the reach of these posts. This paid promotion, often known as ‘boosting’ a post, is priced based on the desired reach and the duration of the campaign. The cost for boosting can vary widely, starting from as little as five dollars a day to several thousand dollars, depending on the scale and scope of the campaign.

The Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) has stated that if a supporter or relative of a candidate manages their advertising campaign, the candidate themselves will be accountable for it, and it will be deemed a part of their official campaign activities. Successful candidates are required to report their campaign expenses within 10 days after the election. As a result, many candidates have increased their investment in social media for campaigning. In cases where a candidate establishes a dedicated social media team or conducts their campaign on social media with external funding, particularly if it involves overseas support for a political party or candidate within Pakistan, the ECP currently lacks the means to effectively monitor these activities. Despite this, the estimated expenditure for a Provincial Assembly election campaign is now projected to be in the range of 6 to 7 crore rupees.

Sohail Khan, serving as the spokesperson for the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, has disclosed that a monitoring system is operational at both district and provincial levels. This system is designed to oversee public grievances and any infringements of regulations concerning advertising campaigns conducted by party workers. He noted that while there is no specific legislation governing political campaigns on social media, the ECP is in the process of formulating a relevant policy. This might entail liaising with administrators of platforms like Facebook and other social media networks.

In terms of regulating advertising campaigns on social media, Khan mentioned that the ECP, in coordination with the Federal Investigation Authority and the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority, is equipped to address and act against any unethical content circulating on social media platforms.

However, Azma Zahid Bukhari, a senior leader of PML-N, likened the dynamics of social media to the phrase “spend money, watch the show,” implying that greater financial investment in social media correlates with increased views and broader post reach. She mentioned that PML-N has established teams across various levels, from central to Provincial Assembly constituencies, which include volunteers. PML-N’s policy is to employ social media ethically, focusing on genuine engagement rather than artificially boosting posts or views, and not allocating financial resources for such purposes.

In a similar context, Qaiser Sharif, the spokesperson and central secretary of information for Jamaat-e-Islami, shared that their party set up a social media wing around 10 years ago. This wing now extends to teams operating at the central, provincial, and union council levels. The party’s shura (council) has ratified Standard Operating Procedures for social media use, emphasizing the prohibition of posting or commenting on any content that is indecent or derogatory.

Sharif revealed that approximately three thousand social media workers have been trained under these guidelines. The budget dedicated to the social media wing is modest and is earmarked annually to cover the costs of computers, cameras, internet, production, and drones. The principal social media team of Jamaat-e-Islami consists of over 25 members, including a diverse mix of roles such as women, cameramen, drone operators, nonlinear editors (NLEs), scriptwriters, among others.

Political observers note that the downturn seen in Pakistani politics is multi-dimensional. There was an era when politicians would run their electoral campaigns primarily with funds raised through party donations, making the electoral process less costly. Former political leaders often recalled that their election expenses amounted to just a few thousand rupees. A prominent personality in Pakistan’s political history, Nawabzada Nasrullah Khan, frequently shared in his interviews how he had to sell his ancestral properties to finance his campaigns.

A notable shift in the political landscape occurred following the non-party elections of 1985, boycotted by the major political parties in Pakistan. This boycott led to a vacuum filled by lesser-known and new political aspirants, many of whom spent millions to secure a place in the assembly. This period coincided with the rampant circulation of drug and arms smuggling money within the country. The 1985 elections saw an unprecedented level of campaign spending. The Election Commission of Pakistan, acting as a passive observer, did not intervene, and candidates continued their lavish spending without facing repercussions for surpassing established expenditure limits. This era also marked the beginning of significant financial outlays in elections, a trend that escalated thereafter.

An experienced PML-N leader, who chose to remain anonymous, recounted his own experience. When he applied for a ticket to contest an election in Lahore, he was warned that his potential opponent from the PPP was extremely affluent and prepared to invest heavily in the campaign. This led him to question whether he could match such financial prowess. Ultimately, he decided against running for election, reluctant to deplete his own savings in what he perceived as an uneven financial battle.

Elections in Pakistan have progressively become more costly over time. Instances were reported where candidates spent between 10 to 20 crore rupees for certain seats. A troubling aspect of elections was the alleged buying of votes, where basic necessities like ghee, flour, sugar, rice, and other food items were reportedly distributed as a means to garner votes. The Election Commission, however, appeared to overlook this worrying pattern.

A significant and unfortunate consequence of this trend was the marginalization of the country’s intellectuals, skilled professionals, and individuals sincerely dedicated to national welfare, many of whom belonged to the middle class. Lacking the financial resources to compete in multimillion-rupee election battles, they were effectively excluded from the electoral process. Another disheartening result was the limited presence of educated individuals in the legislative assemblies, as the political landscape became increasingly dominated by those who viewed politics as a financial investment. The prevailing belief emerged that legislators who had invested heavily in their election campaigns would prioritize recouping their expenditures and then focus on accruing even more funds for subsequent elections.

This particular election is being labeled as the most costly in Pakistan’s history, yet it also represents a major economic event. Consider a scenario where all candidates for the 336 National Assembly seats abide by the spending cap, and each constituency has just three candidates. Multiplying the expenditure limit by the total number of candidates, which is 1008 (three for each of the 336 constituencies), yields an astonishing total of 10 billion rupees. Presently, a substantial number of candidates, totaling 22,751, are gearing up to compete for seats in both the National and Provincial Assemblies.

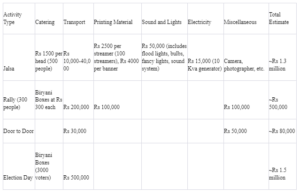

The candidate conveyed to the scribe that each campaign activity incurs a distinct cost. For example, the expenses for door-to-door campaigning differ from the costs associated with holding corner meetings. Below is a chart that illustrates the approximate expenditure of candidates on their election campaigns, providing a clearer understanding of their financial allocation for various campaign activities.

According to the candidate, these costs vary based on the number of participants and the range of activities involved. Consequently, if a candidate is running for a seat in the national assembly, the costs are likely to double due to the significantly larger number of people involved and the increased variety of campaign activities. Therefore, if the election commission sets a spending limit for election campaigns, it becomes challenging for candidates, whether for the national or provincial assemblies, to stay within these financial limits.

Nice topic! Appreciate your selection , very deep and dark , First time i saw such wonderful thing online where campaign cost is boldly post on website, really awesome work, Keep posting