The government of Pakistan is getting desperate. But that isn’t exactly the problem. At this point in time, it is actually a good thing that the government is showing desperation. After all, Pakistan’s taxation system is broken.

Most people don’t realise that running a country is a pretty simple equation in the grander scheme of things. Governments need to regulate, provide a secure environment, social protection, and security to their citizens. To do this, they need money. And to provide these services they tax their citizens. For all of this to work, governments need to collect enough tax to spend as per their budget.

Pakistan consistently fails to do this. And they fail to do this by some margin. The reason, of course, is our persistent inability to collect taxes. The reasons for that are long and storied. But it seems rather than widening the tax net and devloving taxation powers beyond the FBR, the government finds new and creative ways to counter the problem.

The latest addition to the list of brilliant ideas, which includes such hits as blocking sims, is the amendment passed making changes to tax appeal laws in Pakistan. On May 6th, the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) published a series of amendments called the Tax Laws (Amendment) Act 2024 in its official gazette. Interestingly, the act had been presented as a bill to the parliament only ten days earlier. This rapid progression raised several questions regarding the bill but the most important question that comes from the passage of this bill is the motivation behind the act. The act is not necessarily bad and could even help in improving recoveries, but it does not address the core issue.

What prompted the swift passage of the bill? What exactly does the Tax Amendment Act, 2024 entail? How will it affect the average Pakistani? And what implications does it hold for the future of businesses in Pakistan?

The Procedure

To understand what the amendments are, we first have to understand what the procedure is. The tax liability of any person or entity is determined by a tax officer. Essentially, there is someone responsible for judging how much tax you as an individual or a company as an organisation owes the government.

An assessment order by a tax officer is a formal determination of a taxpayer’s tax liability for a specific assessment year. This order is issued after reviewing and examining the taxpayer’s filed documents, along with any additional information or documentation requested during the assessment process on any kinds of tax including income tax and sales tax.

The assessment order specifies the amount of tax due, including any additional taxes, penalties, or interest that the taxpayer must pay. It details the taxpayer’s income, deductions, and exemptions, as well as any adjustments or additions made by the tax officer. In the case of income tax, for example, the filer provides these details himself and the tax officer verifies/ signs off on them.

Hence that order includes a final calculation of the taxable income and corresponding tax liability based on applicable tax rates, and it provides payment instructions and information on the taxpayer’s right to appeal if they disagree with the findings.

This is where our story really kicks off. If a taxpayer disagrees with the tax order, they have the right to appeal this. Small claims often go to senior tax officers while larger claims can go into litigation all the way up to the Supreme Court and often take months and years languishing from appeal to appeal. On many occasions, in fact, tax cases can be some of the most complex judicial decisions to exist. Naturally, there are those that misuse this as well, by delaying having to pay taxes by contesting them over and over again.

This is why the appellant has to either provide a bank guarantee or some percentage of the assessed amount and can then appeal against the assessment.

To understand the problem at its core the readers also need to understand certain adjudicating bodies. The Commissioner Inland Revenue (Appeals), for instance, is an official responsible for hearing and deciding on appeals against tax assessments made by tax officers. They handle disputes related to income tax, sales tax, and federal excise within specified monetary limits.

The Appellate Tribunal Inland Revenue (ATIR) is a high-level judicial body that adjudicates appeals against decisions made by the Commissioner Inland Revenue (Appeals). It handles cases involving significant tax disputes, including income tax, sales tax, and federal excise duty. ATIR aims to ensure fair resolution of tax-related conflicts and its decisions can be further appealed to higher courts.

Particularly, one could file a reference/appeal with the Commissioner Inland Revenue (CIR) Appeals, and upon dissatisfaction re-appeal to Appellate Tribunal Inland Revenue, and so on to the respective High Court. But this was the case, until now. From now on, things are about to take a dramatic turn.

The Amendments

When presenting the bill to the parliament, the Federal Minister for Law and Justice Azam Nazeer Tarar revealed that there are pending tax cases amounting to Rs 2,700 billion across various appellate forums. These forums include Commissioner Inland Revenue (Appeals), Appellate Tribunals, High Courts, and the Supreme Court of Pakistan. The amendments hence aim to liquidate a significant number of these pending appeals, thereby freeing up substantial revenue. Over the years, the appellate system has faced issues such as arbitrary constitution of benches, inadequate number of benches, and delays in case fixation and disposal.

An arbitrary figure, tracking which back could take ages of old case files, led the parliament to pass the bill in a rush, and with an exemplary swiftness, which is testament to Pakistan’s renowned bureaucratic agility, the bill was given the presidential assent and then the status of an act within a week.

At its core, the Tax Amendment Act 2024 proposes significant changes to the handling of tax appeals, particularly focusing on the role and jurisdiction of the Commissioner Inland Revenue (Appeals) and the Appellate Tribunal Inland Revenue (ATIR).

Here, we delve into the details of these amendments only.

The Commissioner Inland Revenue (Appeals) will now only handle income tax appeals involving amounts up to Rs 20 million for income tax, Rs 10 million for Sales Tax, and Rs 5 million for federal excise. For any tax appeal above the aforementioned threshold, the responsibility will shift to the Appellate Tribunal Inland Revenue (ATIR).

The ATIR is supposed to handle all appeals involving amounts above the specified thresholds (Rs20 million for income tax, Rs10 million for sales tax, and Rs 5 million for federal excise duty). The shift, as per the FBR, aims to streamline the appeals process and ensure quicker resolutions for high-value cases. What this means is that the higher the amount, the quicker the resolution and the quicker the realisation.

Unlike before, the time required for the filing of these appeals has also been reduced, from 60 to 30 days in hopes of making this process quicker. With all these big cases now shifted to the ATIR, the ATIR is mandated to decide on these transferred appeals within a six-month period. This is expected to clear the backlog of cases accumulated in tax appeals.

Similarly, all cases currently pending before the Commissioner Inland Revenue (Appeals) that exceed the new monetary limits will be transferred to the ATIR. The ATIR will begin addressing these cases from June 16, 2024, ensuring decisions are made within the stipulated six months.

One may wonder as to where would the ATIR, a small authority tasked with important decisions, run into such processing capabilities. By a careful estimate, this will increase the ATIR’s workload by twice if not more, considering that any disputed decision of the CIR(A) is also the ATIR’s responsibility. In a set of separate amendments, the composition of the ATIR is also going to change, one which will end the distinction between judicial and accountant members of the ATIR.

Moreover, the fee for filing an appeal or reference has been increased by at least 4x and at most 50x for the highest authority.

In other changes, the appeals to the Tribunal and references to the High Court must be filed within 30 days of receiving the order. Moreover, the High Court is required to decide on these references within six months of filing, further ensuring timely resolution. Similarly, all the durations for appeals and stays have been either defined or reduced, making it mandatory to finish one year’s tax appeal within the same year.

Any appeal that hence asks for a stay in the high court is required to pay 30% of the tax determined by the ATIR.

The problems

The goal is to expand the tax base, which is essential for strengthening Pakistan’s economy. However, the amendments under question are only relevant to the set of taxpayers already paying their taxes. The bill applies to all individuals, entities and companies, whereas it has special provisions for State-Owned Entities which, for the purpose of simplicity, will not be discussed in this article.

Now, when the bill was presented in the parliament, the opposition Leader in the National Assembly, Omar Ayub, suggested that the proposed bill should be thoroughly discussed in the Finance Committee. This indicated the need for broader consensus and detailed scrutiny to ensure the amendments effectively address the issues at hand. Ironically, nothing of the sort was done.

The bill was bulldozed, and little to no time was given for technical discussions to be had by the elected representatives of the people. The bill gained the presidential assent on the 3rd of May and was published in the Gazette on the 6th of May, all after being presented in the parliament in the last week of April.

In this process to expedite the taxation process and then to expedite the Act, a few important factors were however overlooked. These anomalies that hence are apparent in these amendments might pose a serious question on their enactment. It gives rise to not just loopholes, but as found out by Profit through a series of interviews, genuine violations of the constitution itself.

Anomalies

The first and foremost problem arises with the dates of publishing and the date of presidential assent. Although this might not appear to be a major problem, tax professionals seem confused on the status of the appeals that were filed before the presidential assent and between the dates of presidential assent and the publication of the law.

There is a confusion about the date of operation (effective date) of the Tax Law Amendment Act. One perspective argues it is effective from May 3, 2024, while another viewpoint suggests it is effective from May 6, 2024. If the effective date is May 3, 2024, what recourse is available for taxpayers who filed appeals on May 3, 4, 5, or 6 at the wrong forum or after the specified time in the new law?

One of the problems as pointed out earlier is that of workload for the ATIR, despite the increased fees there is absolutely no “budget” available to track these payments that are to be made to the tax department. Moreover, the composition of the ATIR as given by the amendment is still the 5 members, with a much larger workload and increased number of cases, there are only two ways in which the ATIR can operate. One, by not reviewing the cases in detail and hence clearing the backlog or two by creating an even larger bottleneck, this time concentrated at the level two of the appeals hierarchy.

Another important issue that is pertinent to mention here was raised by renowned tax consultant Sharif ud din Khilji, while talking to Profit. He mentioned that there was an unclarity regarding the availability of a public budget for the increased adjournment and appeal fees. The adjournment fee from the ATIR i.e at least Rs. 50,000 (previously at least Rs. 1,000) and the Appeal fees i.e. Rs 20,000 previously (Rs 5,000) is to be made in the name of the tax department. It is unclear whether any of this amount can be budgeted yet.

There is also the establishment of a political relationship between the government in power and the Chairman of the ATIR. Since the Federal Government will have the authority to dismiss the Chairman of the Appellate Tribunal on the performance committee’s recommendation, it creates a relationship of subordination of the Chairman to the performance review committee and in turn the Federal Government. We will later find out why that is a bad thing.

Violations and Ambiguities

While the last point may seem like an anomaly to some, it can be construed as unconstitutional by many. Say a person has an appeal against the assessment of tax amounting to Rs 20,000. He feels that he does not owe this much and is rather rightfully only liable to pay Rs. 15,000. Then just to file this complaint twice, once with the CIR (A) and once with ATIR, that person will require Rs. 10,000.

Let us assume that due to any personal circumstance he has to adjourn or postpone the hearing, for this reason only, the person will have to pay up at least Rs 50,000. What will this average person do? Simple, he will just not file his taxes. And that is the core of the problem that the FBR has failed to address, the environment of mistrust, and the culture of lack of power with the common man. When another person with a tax liability in excess of 30 million walks scott-free and also gets to keep his money based on his contacts within the ATIR, then why would an average citizen be motivated to file?

Since the cost of getting a stay on any basis requires 30% of the determined tax, this just becomes a violation that has a price tag. Legal experts argue that the excessive fee increases and the 30% upfront payment go against the spirit of the constitution.

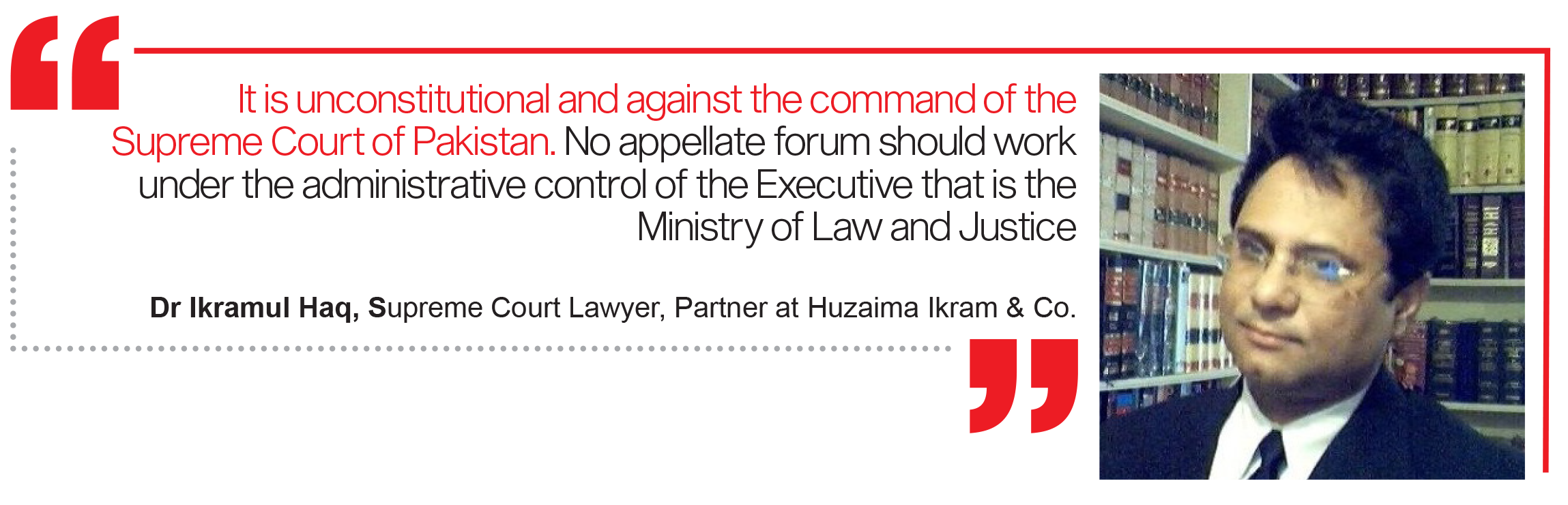

Dr. Ikramul Haq, a Supreme Court Lawyer, and Partner at Huzaima Ikram & Co. talking on the matter stated that “The enormous enhancement in the quantum of fees for filing appeals/references and compulsory payment of 30 percent of disputed demand for stay by High Court are unconstitutional, amounting to denying the fundamental right of free and unfettered access to justice. It goes against the article 10A of the constitution of Pakistan which affords every citizen a fair trial.”

It is a well-established fact in the tax world that mostly harsh, arbitrary and excessive orders are passed to show “performance” and “collection” by adjudicating officers that ultimately are adjudicated on in the Tribunal or by higher courts—only those sustains that are legal and based on reasons and evidence. Others become an opportunity of corruption for the Tribunal officers.

Higher appeal fees also means that the Bureau officers get more leverage to blackmail the taxpayers. Prospective taxpayers, to save themself from the high appeal fees and political judgement process, not to mention the serious toil of the legal process that comes with it, will find it easier to pay “rent” to the tax officers.

This brings us to another legislation that was passed in parallel with these amendments and is called the “Appellate Tribunal Inland Revenue (Appointments, Terms and Conditions of Service) Rules, 2024”. According to these rules not only will the composition of the Tribunal change (increase in number) but the salaries will also increase. So much so that members are now going to make salaries equivalent to those of high court judges, while the chairman will make as much as the salary of the Chief Justice of the High Court. Meanwhile members on deputation get Rs 700,000 in tribunal allowance along with their last drawn salary. Now that is a high incentive to work in the tribunal.

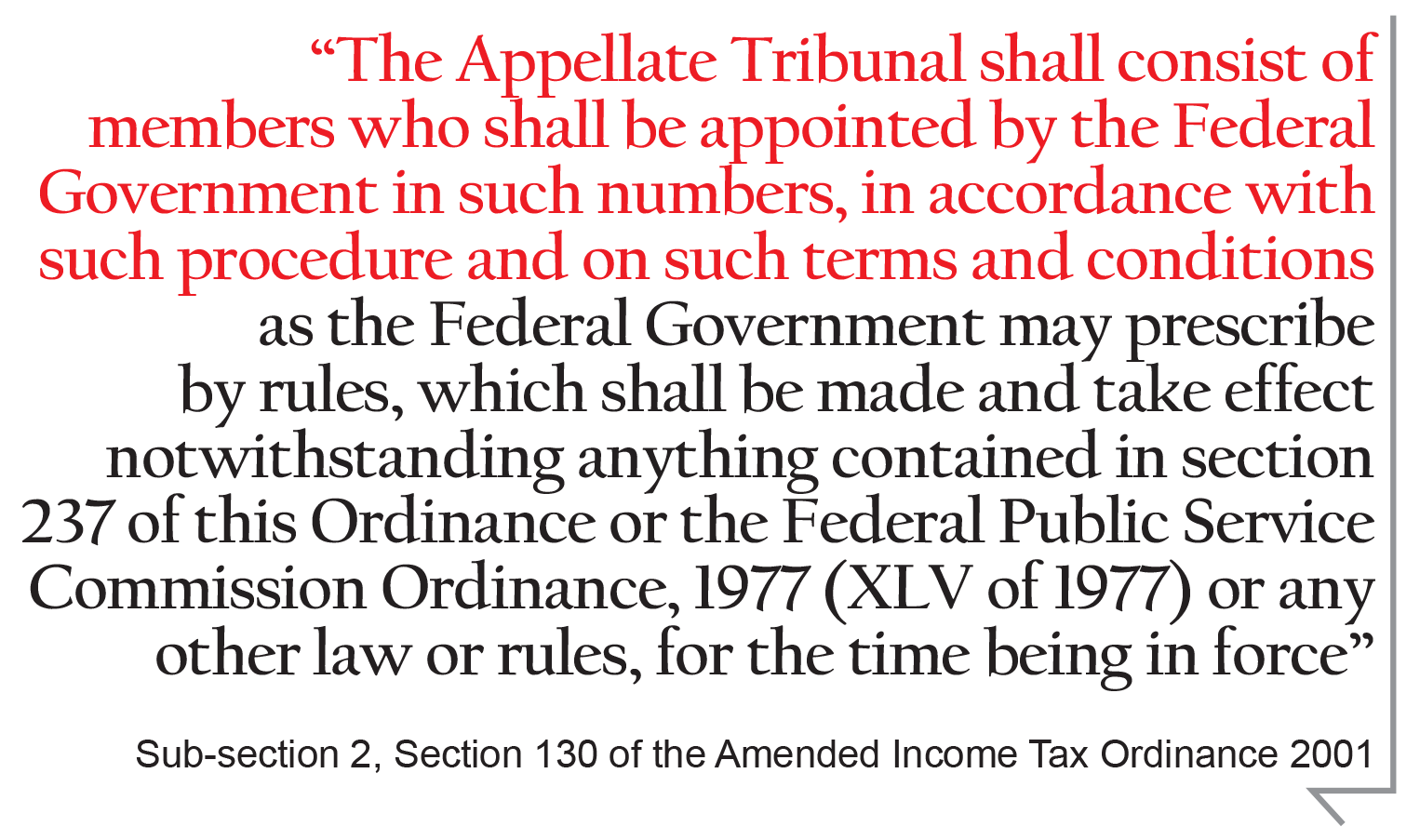

Just looking at the hirings in the last 1 year in Appellate Tribunals in the last two years, one could accuse them of political hirings but now these hirings will no longer be political. Since the new amendment allows for it!

According to the subsection (2) of the substituted section 130 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001: “The Appellate Tribunal shall consist of members who shall be appointed by the Federal Government in such numbers, in accordance with such procedure and on such terms and conditions as the Federal Government may prescribe by rules, which shall be made and take effect notwithstanding anything contained in section 237 of this Ordinance or the Federal Public Service Commission Ordinance, 1977 (XLV of 1977) or any other law or rules, for the time being in force”.

Hence if the government did have any say in the matters of the Public Service Commission, it doesn’t need it anymore as far as tribunal hirings are concerned. With both the stakes and incentives this high, the tribunal is set to take on an allegedly political role. The increased number of hirings is also indicative of that.

Talking about this particular amendment Dr. Ikram states that, “It is unconstitutional and against the command of the Supreme Court of Pakistan. No appellate forum should work under the administrative control of the Executive that is the Ministry of Law and Justice. This principle was laid down by the Supreme Court of Pakistan in Government of Balochistan v Azizullah Memon PLD 1993 SC 31 that separation of judiciary from executive is the cornerstone of independence of judiciary. It is shocking to see how this clear command under Article 189 of the Constitution was ignored by the Ministry of Law and Attorney General of Pakistan, who also briefed the legislators on the importance of this amendment.”

Another factor that was pointed out while talking about these amendments was setting a time limit on the High Court. According to our sources, “Giving directions to the High Court, which is also a constitutional court, is blatant violation of the Constitution, and encroachment on the independence of judiciary. Since there is no mention as to what would happen in case a Court does not decide the reference within six months of the date of its filing, this provision is directory in nature and not mandatory.” This makes the entire process moot, as the appeals are likely to stack up at the high court level if not the ATIL level, and the FBR walks home with 30% of the tax, until the case is resolved, which as it seems is the prerogative of the high court.

It is also worth noting that CIR (A) is not an independent appellate forum yet the CIR (A) has now been made the final fact finding authority. No statutory remedy is now available on the question of fact determined by the CIR (A). This sure does expedite the process of appeals but does it make the process more or less just, remains a question that needs answering. Another problem that was pointed out by officials was the excessive adjournment fees without the provision for a case with genuine hardship.

The amendments, in general, can be termed extractive and not transformative. Another ironic part of the amendment is the constitution of the adjudicating bodies. It is ironic that it is the same FBR officer who was once a tax officer and quite possibly once the Commissioner (Appeals) who will get promoted to the ATIR as the accountant member. By what logic will he suddenly have a change of heart and knowledge and become eligible to hear a case of a higher monetary threshold than he was before.

According to sources close to the developments in the Appellate Tribunal, more particularly in Punjab, it has been revealed that a lot of devout party workers have been appointed in the various tribunals across Punjab in particular making this another questionable step in a series of questionable steps.

To sum it all up

With the growing concern of revenue shortfall, an amendment to remove the red tape in the appeals process can be seen as mandatory. Pakistan needs to run into some money, and it needs to do that fast. That is one of the reasons why the IMF is onto Pakistan for increasing the tax net, and the FBR is flapping its arms in all directions either by blocking the SIMs of non-filers or by shutting doors on justice seekers when it comes to value assessment. It is very likely that when asked, the FBR, the Federal Government or even the SIFC, present the IMF as a scapegoat for these amendments.

Sources told Profit that this is not the first time something like this will be tried under the guise of the IMF conditions, in fact it has been tried before a couple of decades ago. The only difference was that at that time, Pakistan was under a martial law and an active war.

The current government, contrary to the 18th amendment and the Supreme Court’s directives, instead of freeing the tax tribunals from the control of the executive, is further taming them, bringing them directly under their control.

Experts suggest that a writ petition in the High courts and eventually the Supreme Court with reference to article 199 of the constitution shall be filed and the problematic amendments must be reversed.

By making the appeals expensive, not only has the government tried to close the doors on true assessment of value, but has provided added protection to the state machinery responsible for making these assessments. One could argue that these were necessary steps that needed to be taken, however, the question that is needed is. Does this increase the tax net? Does it bring new people into the net or does it discourage those entities already in the net to get out because they might not get a fair shot? If the latter is true, no service to the national exchequer will be done by putting these amendments in effect.

Beating the same old drum

This is the fourth time we are ending a story on taxation with the exact same point. But we keep repeating the same point over and over again because it is true. No measures of this sort will matter unless Pakistan fixes its taxation philosophy, and fixing it is easy because we are not currently taxing in the spirit of our constitution.

The real problem is that Pakistanis are taxed unfairly and those that should be paying the lion’s share end up paying nothing. Just take a look at Pakistan’s tax structure. Tax structure refers to the share of each tax in total tax revenues. The highest share of tax revenues in Pakistan in 2020 was derived from value added taxes / goods and services tax (39.8%). The second-highest share of tax revenues in 2020 was derived from other taxes (33.3%).

In comparison to Pakistan, countries in the Asia-Pacific region only collect about 23% of their taxation from goods and services taxes — meaning Pakistan’s average is almost double. Why is this the case? The biggest reason of course is that taxation in the country is centralised. The FBR collects almost all taxes (even the ones that should be collected by provinces under the 18th amendment) and then those collections are then given to the provinces in the form of the NFC award leaving the federal government with very little spending money. In an earlier interview former Finance Minister Dr. Hafiz Pasha, while talking to Profit, lamented that, “We as a country have failed to implement the beautiful 18th amendment. The implementation has been slow and weak.”

Since the share of the provincial governments, under the NFC awards, over the last few years has been increased from 40% to around 57%, it has provided the provinces with very little incentive to develop their own revenue sources. Despite having access to the two biggest cash cows, services and agriculture, the share of provincial tax revenue is close to 1% of the GDP. “You would be surprised to know that the corresponding number for Indian provinces is around 6% of the GDP, with similar fiscal powers,” says Dr. Pasha.

The solution of course is right in front of us: devolution. More than just being a third tier of democracy, having a local bodies system means having a new economic process. In essence, it is not just a new administrative stratification, but also involves the dispensation and spending of money. Things such as education and health that people automatically look towards the provincial government for would now be handled by local representatives. Perhaps most crucially, the ability of local governments to collect taxes and release their own schedule of taxation allows them to make their own money and spend it on themselves rather than waiting for the benevolence of the provincial or federal government.