About one in every three cups of tea consumed in Pakistan is using Tapal Tea. As a brand, it is one of the most well-known names in the country, a market leader in a category that touches everyday consumption in virtually every single household in Pakistan.

In a country with a thriving capital market, such a company would either already be public, or its choice to remain private would be an anomaly. In Pakistan, however, Tapal’s decision to remain private is entirely within the norm.

News hit the wires this past week that Pakistan’s equity markets are on the verge of being downgraded by the global benchmark provider MSCI from its Emerging Markets Index to its Frontier Markets Index. This is as opportune a time as any to ask: what is it about the Pakistani capital markets that keeps some of the country’s biggest, most prominent corporate names from becoming publicly listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange.

Unlike most other pieces that will address this question this week, we decided to use a real case study: Tapal, a company that is probably worth a lot of money and, by some admittedly aggressive valuation methodologies, may even be worth more than $1 billion. (Wait, so if we are admitting that Tapal is probably worth less than $1 billion, is the headline just clickbait? Yes. Yes, it is. But now that we have your attention, please do read on.)

What is the story of Tapal and what makes it such an iconic Pakistani brand? What would it be valued at if it decided to list itself on the stock exchange? Why does it choose not to? And how does the decision of companies like Tapal affect Pakistan’s downgrade on the MSCI indices?

The story of Tapal

The tale of this company begins shortly after Partition in Jodia Bazar in Karachi, where the Tapal family began their tea business: importing tea from Sri Lanka and then selling it wholesale in the markets in Karachi. Jodia Bazar is, to this day, one of the largest wholesale markets in Pakistan. It helps that it is located just a few miles from Karachi Port and is located in the city that has the single largest concentration of the Pakistani urban middle class.

The founder of the company was Adam Ali Tapal, grandfather of the current CEO Aftab Tapal. The store in Jodia Bazar soon grew as Karachi went from being a relatively minor city in British India to becoming the largest city in Pakistan. The tea business outgrew the store and began marketing itself far beyond the retailers and occasional consumer buyers who would come to the store.

It took Aftab joining the family business in 1975 after having received a foreign education, however, for Tapal to go from being a thriving mid-sized business to becoming the household brand name it is today. The foreign educated son returning to shake things up in the family business may be a bit of a cliché, but sometimes it really is true, and it certainly seems to be the case for the Tapal family.

The first thing that Aftab noticed and changed was the packaging. When you are competing against the likes of Unilever, with their sophistication and high-quality brand management, you should probably start by at least putting your name on your product, and then maybe making the packaging more appealing to the consumer.

The company began expanding in all sorts of ways. It set up a massive factory in Korangi, one of three major industrial areas in Karachi, to set up a packaging plant. Tapal also went beyond the Ceylon tea that was the norm in Pakistan and introduced tea from Kenya. And the company went after both the major segments of the market: the slightly more affluent urban middle class that preferred granular tea, and the rural market that could only afford the tea dust.

Tapal began to make a name for itself as the third name that Pakistanis knew of when they thought of tea. Unilever was still the big name with Lipton, and then there was the other British company in the tea business: Brooke Bond. For a local company to make its name in that milieu was no mean feat. For them to have continued to hold their ground even after Unilever bought Brooke Bond to become the dominant tea player in Pakistan… well, that just takes a lot more than luck. It takes skill and determination.

So how big is Tapal?

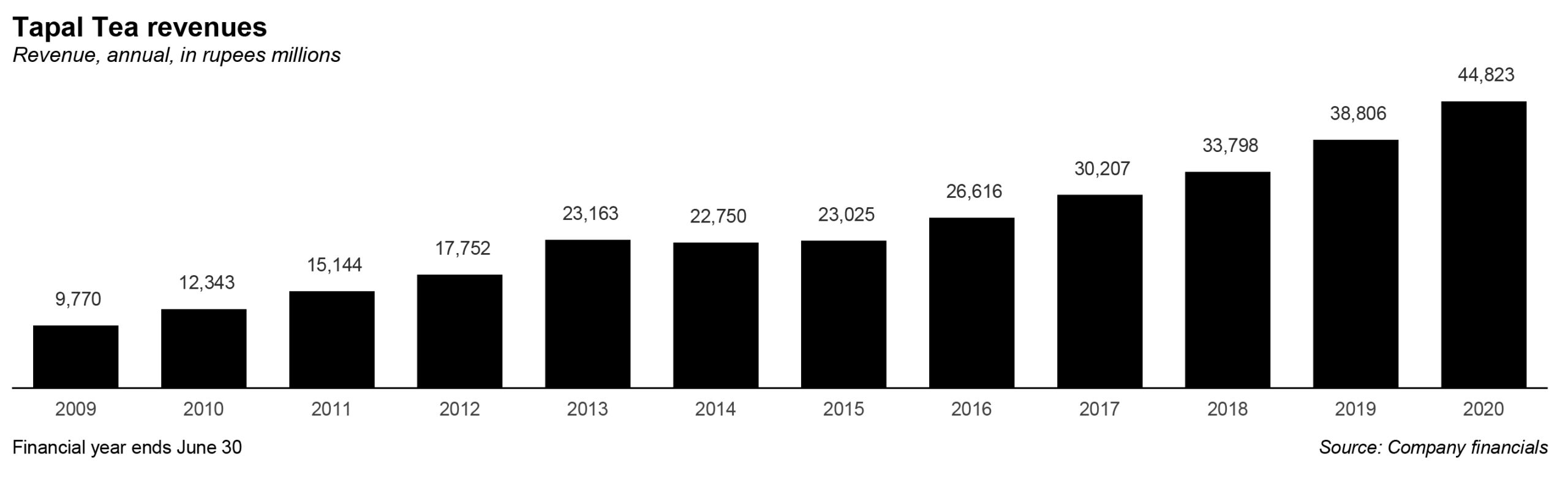

In a phrase, very big. As of the financial year ending June 30, 2020, Tapal had gross revenues just short of Rs56 billion and net revenues (after subtracting trade discounts and sales taxes) of Rs45 billion. This is one of the biggest food and consumer goods companies in Pakistan, bigger than many names that are currently publicly listed.

It has also managed to retain a market leading position in a segment that is still dominated by a well-financed foreign incumbent with all the capital and financial muscle it takes to stay number one. And did we mention that it has managed to not just grow its revenue at a healthy pace, but also increase its profit margins?

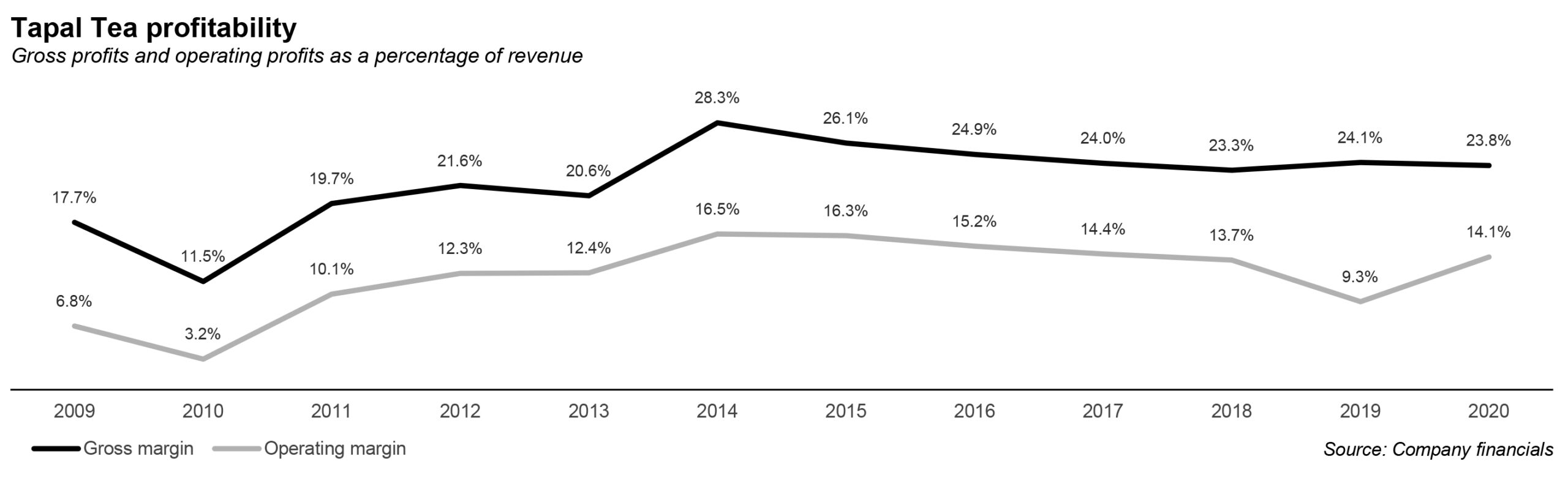

Gross margins have gone from as low as 11.5% in 2010 to around 24% for the past five years, meaning that even in as commoditised a market as tea, Tapal’s brand name ensures that it can command hefty margins. This is especially impressive when one considers the fact that the tea is imported, meaning that the volatility of the rupee is a significant factor that could easily dampen the company’s pricing power.

That does not mean that the company’s product is something people are willing to pay for, even when prices rise sharply. Intuitively, it makes sense, though. Tea is something most Pakistani adults consume every day and for something in such daily use, you want to trust the quality of the product you will be consuming. Tapal’s brand gives them that trust.

One other factor that makes Tapal’s achievement even more impressive: tea used to be categorized by the government as an essential food item and subjected to minimal sales taxes. However, since 2017, tea has been subjected to a full sales tax regime. To have your core product go from facing very little in terms of sales taxes to suddenly having to pay full sales taxes – when you have several informal sector competitors who evade sales taxes – makes the company’s ability to command high margins even more impressive.

Brand-building, however, is not all there is to running a successful business. There are operations, supply chains, distribution, and administrative costs, all of which can start rising rapidly if a business is not managing a tight ship. On that front, too, Tapal appears to be a well-run company.

Operating margins – what is left over after a company is done paying its suppliers, all employees, all rent, utilities, and other expenses – went from a low of 3.2% of net revenues in 2010 to 14.1% in 2020 and have been consistently above double digits for most of the past decade. Tapal is not just a recognizable consumer brand: it is a well-run business that is able to not just maintain its profitability, but grow it as it achieves economies of scale.

If this was a company that was looking for outside investors, it would find them quite easily.

What is Tapal worth?

We want to state categorically: we have absolutely no reason to believe that Tapal is seeking an initial public offering or an equity sale of any kind. Owing to timing issues, we were not able to speak to the company’s management ahead of the publication of this story, but Profit is not in any way implying that Tapal either needs the equity investment or wants it. They most certainly do not, as far as we are aware.

The point of even asking this question is to explore just how valuable one of Pakistan’s best-run private companies could be, as a means of commenting on what is available to public equity investors versus what could be available to investors if the market were deeper, and better functioning. With those caveats aside, let us dig into our rudimentary valuation for Tapal.

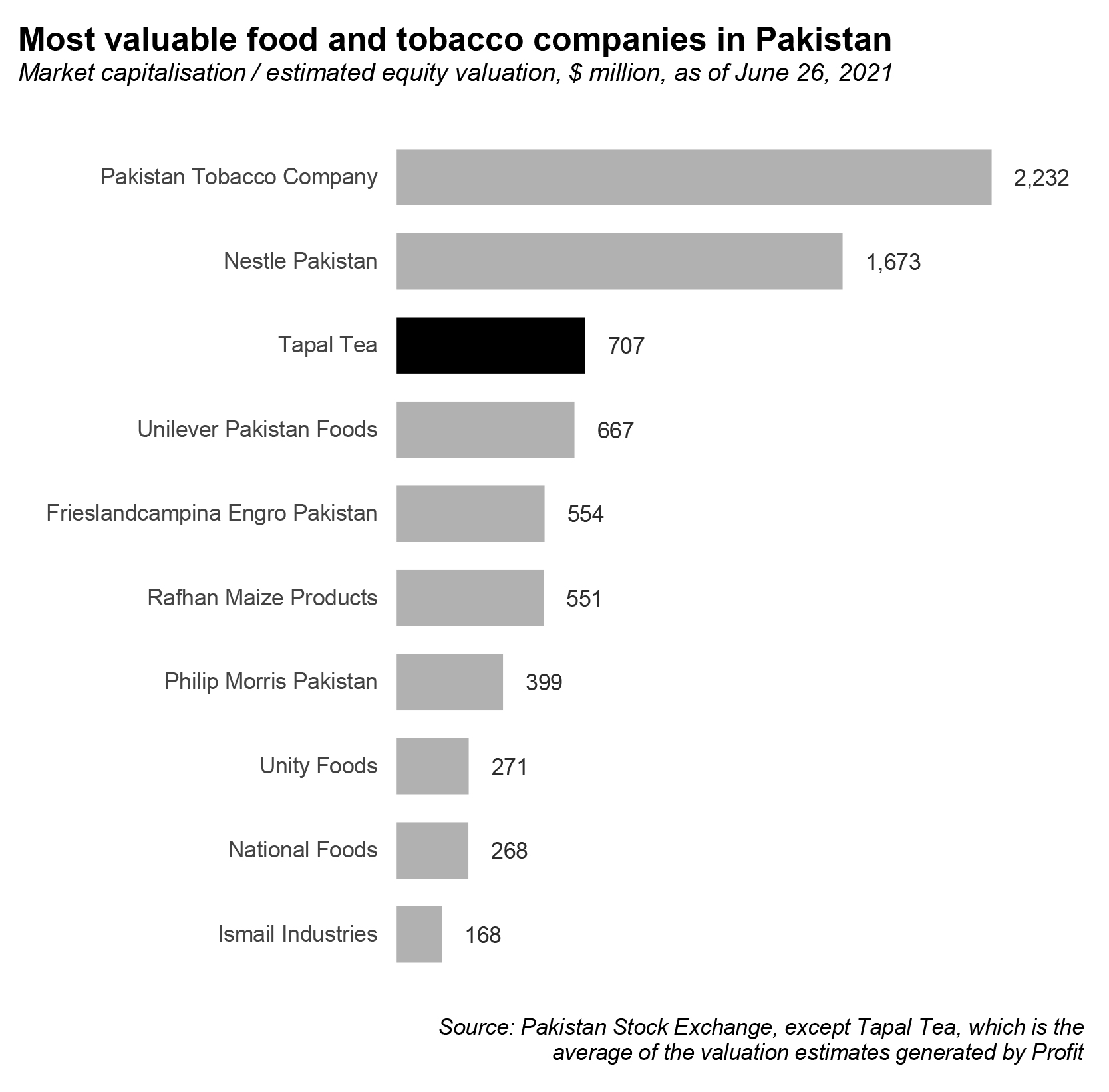

To conduct a valuation of Tapal, we looked at its financial metrics – revenue, profits, etc. – and compared them to those of publicly listed food and tobacco companies of a comparable size. We compiled a list of nine publicly listed companies that appear to be most directly comparable in terms of size. They were Pakistan Tobacco Company, Nestle Pakistan, Unilever Pakistan Foods, Frieslandcampina Engro Pakistan, Rafhan Maize Products, Philip Morris Pakistan, Unity Foods, National Foods, and Ismail Industries.

In an ideal situation, we would have had a tea company to compare directly, but Pakistan’s economy is too small and has too few players in most markets for that to be available, let alone having a directly comparable publicly listed competitor. The broader category is the best we could do, and for the purposes of this analysis, that is probably good enough.

We then looked at those nine companies across five valuation multiples:

- Enterprise value to revenue (EV / Sales)

- Enterprise value to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EV / EBITDA)

- Enterprise value to earnings before interest and taxes (EV / EBIT)

- Price to earnings (P / E)

- Price to book value (P / B)

We looked at the valuation of each of these companies based on those metrics as of their publicly traded prices at the close of trading on June 26, 2021. We then compiled the average for the nine companies in question, and then applied that average multiple to the relevant financial metric for Tapal from financial year 2020 to arrive at an estimated valuation for Tapal.

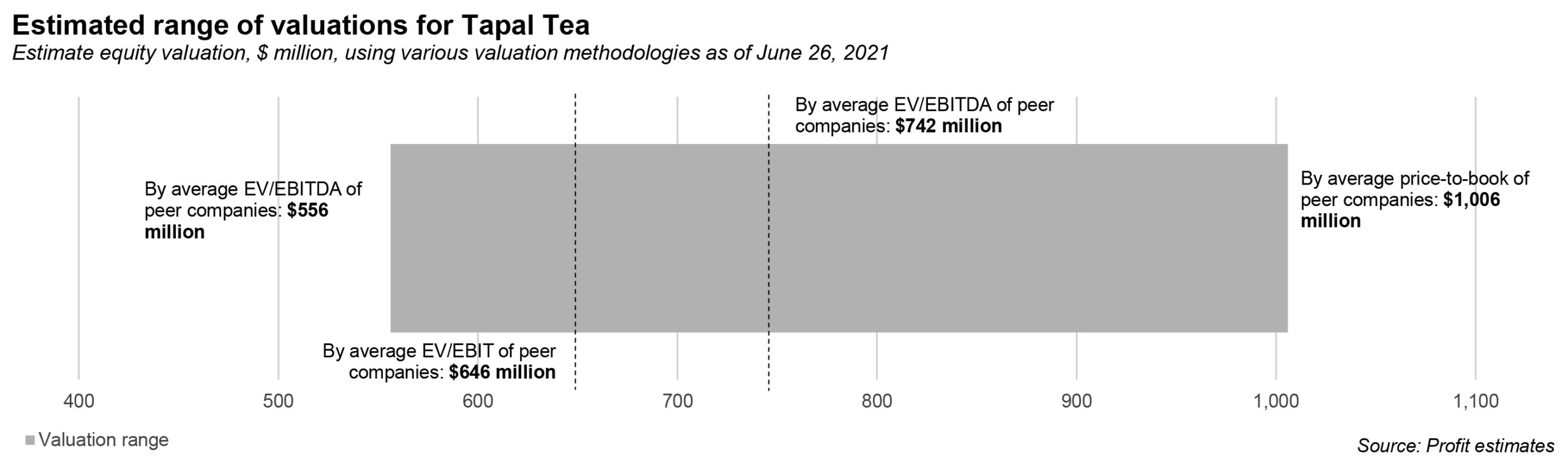

Like any valuation exercise, we got a range of values. The lowest was on the basis of EV / Sales, where the peer group had an average enterprise value multiple of 2.6 times most recent 12-months revenue. By that metric, Tapal is worth approximately $556 million. The highest was through price-to-book value, where the peer group multiple was 9.48 times book value, which resulted in a valuation for Tapal of $1 billion.

If Tapal were to list itself on the public markets, it would likely find its valuation somewhere between those two numbers. It would be one of the most valuable companies listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange and the third most valuable food and consumer goods company, behind only Pakistan Tobacco and Nestle Pakistan. (Yes, it would probably be worth a bit more than Unilever Pakistan Foods and Frieslandcampina Engro Pakistan.)

So is Tapal worth $1 billion? Probably not, but it is close enough to where it will probably cross that threshold within the next three to five years.

The chicken-and-egg problem

So why even talk about the valuation of a company that has no intention of ever being listed publicly or even being sold to other private investors?

Because it represents a core problem that Pakistan’s equity markets face: some of the most attractive businesses in Pakistan remain private and have no intention of ever being publicly listed. And even those that do become publicly listed tend to remain closely held, which means there is often not enough trading volume in those stocks for investors who may want to buy their shares.

It becomes a chicken-and-egg problem: global investors have limited interest in Pakistan because so few of the most promising investments in the country are publicly listed, and so few of them are publicly listed because not enough investors want to come into the market, meaning that the companies that do consider getting themselves publicly listed do not get attractive enough prices to come to market.

Tapal, for instance, is a cash-rich company. Let us assume the hypothetical scenario in which they do decide to come to the market and list 20% of the company’s shares on the Pakistan Stock Exchange. Assume for a minute that the valuation they receive is around $750 million. So in order to sell 20% of those shares, they would get $150 million.

That seems promising enough until you realise that Tapal has very little debt on its balance sheet and that they could raise an equivalent amount in loans from banks while giving away 0% of their ownership. To entice them into the market, the price they would have to receive from it would have to be quite attractive. But in order for that to happen, there would need to be a bidding war for Tapal shares, which means that those with big cheques to write – the international investors – would need to be interested.

In order for enough of them to be interested in Tapal, however, they would first need to be interested in the Pakistani market, but because so many companies like Tapal are not listed (and very few interesting companies are publicly listed), most of the big-cheque international investors stay away.

You see the circularity of the problem?

The index downgrade

This is a problem that came to the fore over the past couple of weeks when the world’s leading equity investing benchmark provider – MSCI, Inc. (formerly known as Morgan Stanley Capital International) – announced that it was reviewing Pakistan’s place in its widely followed Emerging Markets index and will downgrade Pakistan to the lower-prestige (and much less followed) Frontier Markets index.

What does all of that mean? Briefly, investment management companies all around the world that invest in global stocks tend to use the MSCI indices as benchmarks against which to compare their performance. Each country has its own market index, but if you invest outside your own country, especially if you invest across multiple countries, you probably use the MSCI indices as your benchmark.

Why does this matter for Pakistan? Because nearly all of the international investors who invest in Pakistan are the ones who create multi-country investing portfolios and therefore utilise the MSCI indices as their benchmarks. That means that if MSCI suddenly decides that a country no longer falls into one index, investors who benchmark themselves against that index no longer feel the need to buy stocks in that country. Indeed, they may actively seek to sell what they do own there.

Why is the Emerging Markets index a bigger deal than the Frontier Markets index? Let us give you a very simple set of data that will answer that question. There are currently $14.5 trillion worth of assets that use the MSCI indices as their benchmarks. Most of those track developed markets, but about $1.8 trillion of that tracks the MSCI Emerging Markets indices. The equivalent number for the MSCI Frontier Markets index? About $20 billion.

The downgrade, in other words, matters quite a bit. And, embarrassingly for Pakistan, this is not the first time that Pakistan has been downgraded from the Emerging Markets index to the Frontier Markets index. MSCI first started including Pakistan in its indices in 1993, and included Pakistan in the Emerging Markets Index in 1994. However, after the Karachi Stock Exchange stupidly decided to effectively shut down in August 2008 in the face of a market crash, MSCI kicked out Pakistan from its Emerging Markets index in December 2008.

It took nearly a full decade of effort by Pakistan’s capital markets professionals, but by June 2017, MSCI was willing to reclassify Pakistan into the Emerging Markets index. Now, however, it looks like Pakistan’s place in the Emerging Markets index will be short-lived, and the country may get kicked out as soon as September of this year.

The better index?

The downgrade is certainly bad, but there are those who believe there is an upside to this. The most sophisticated of these is Mattias Martinsson, chief investment officer of Tundra Fonder, the Stockholm-based investment management company that is one of only a handful that operates a Pakistan-specific fund.

In a note he published on LinkedIn, Martinsson argued: “Personally, I think it is a good idea. At 2 bps (0.02%) of MSCI EM, Pakistan will continue to be ignored. The theoretical weight in MSCI FM would be 2% but Pakistan would probably become a 6-10% weight given its current liquidity and the theme it represents.”

He went on to suggest that the EM index is too China-dominated for any of the smaller countries to get any interest from global investors.

“Since 2010 China’s weight in MSCI EM has gone from 15% to 40%, killing the interest for smaller emerging markets. Today four markets (China, Taiwan, South Korea and India) make up more than 80% of MSCI EM. The fifth largest market (Brazil) stands at just above 5%. For the active managers generating 6% alpha from the top four is equal to generating 30% on average from the remaining 28 markets. It is a no-brainer where they should focus. Smaller EMs like Philippines, Indonesia, Egypt etc are forgotten. The fact that index funds have become significantly more popular has of course aggravated the focus on the large EMs further. Neither actively managed funds nor index funds (for more obvious reasons) have incentives to become experts in small emerging markets.”

He certainly has the numbers on his side. Even if you look at just the index values alone, the Frontier Markets index looks more attractive for Pakistan. At 0.02% of an index tracked by $1.8 trillion in assets, Pakistan’s share of those assets comes out to a paltry $360 million. MSCI, however, said that if Pakistan moves to the Frontier Markets index, its share of that would be 5.8%. Assume that only $20 billion track the MSCI Frontier Markets index, that puts Pakistan’s share of the global index-linked investing market about $1.16 billion, or about 3.2 times higher.

So, what is better? What would entice companies like Tapal to list themselves on the market? The specialist investors who manage those Frontier Markets funds would certainly appreciate it more, and they can clearly allocate more of their money towards Pakistan to justify a good price.

But ultimately, it will take the trillions sitting in Emerging Markets funds and beyond to get that bidding war going that will offer the truly attractive price to Tapal. The solution, then is to not just make it into the Emerging Markets index, but also have a reasonable weight there. But for that, we would first have to stay in the index, and for now, that looks increasingly difficult.

It’s worth 250 million USD.

Tapal may launch it’s IPO to register in Pakistan Stock Exchange as well to start trading of its shares

Hi Writer,

I would like to know how did you research this and the fact every third cup of tea drank in Pakistan is Tapal ?

A USD 1 Billion ? Splash cold water on your fave, drink some coffee and revise this article.

It is obvious from your comment that you have not read the full article. May i suggest you to get the subscription by paying a few hundred rupees, before suggesting to the writer for a revision.

Being Pakistani, I love to take TAPAL DANEDAR… it’s becoming National Trademark

Most of the large businesses in Pakistan are family dominated.

Tapal sells instant coffee and if they start exporting it along with their tea products, yeah, A billion dollar valuation is very plausible.

isometric projection

movable office walls