There is volatility and then there is madness. What happened in Pakistan’s currency open market in the past two weeks falls squarely in the latter category.

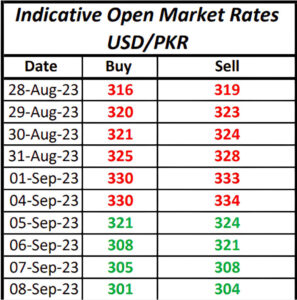

The unprecedented fluctuation saw the dollar go from 319 to 334 in six days and then from there, down to 304 in the following four days. Some quickly attributed this to news of twin $25 billion potential investments, from UAE and Saudi Arabia, over the next 2-5 years. This makes some sense but not enough to explain a Rs 30 appreciation against the US dollar.

Most market experts believe and what is more plausible is that,“danda chal gaya”. There were warnings prior to it, the move was swift, fast and most importantly, clearly very effective.

What problem needed fixing? How was it created, what measures were taken to introduce such a massive correction and what new problems could this create? Who did it? Profit explains.

But before we dig deeper into the issue at hand, it is important to understand the workings of the interbank and open markets and how they are related.

Interbank – The sober compliant one

The interbank is essentially a market exclusively made for and participated in by banks. Each bank, through its treasury department, accesses the interbank market to buy and sell rupees, US dollars and rupee-denominated investment instruments as well. For the purposes of this article, we will only focus on the US dollars.

There are various purposes for which banks would want to use the interbank market. One primary objective would be to fulfil the needs of dollars for the banks’ customers. Let’s say, for example, a textile exporter has received payment of $100,000 against the denim jeans he sold to a customer in the US. The exporter will receive this payment at his bank and as per rules, is now ready to exchange these dollars for rupees.

He will call up his banker and ask for the highest dollar rate possible. The banker gives him the prevailing interbank buying rate, there is some negotiation and an amount of $100,000 in export proceeds is settled at a rate of Rs 305 per dollar. The exporter gets his Rs 3 crore and 5 lacs in his Rupee account with the bank and for all intents and purposes, his transaction is done.

Note that the bank in question has effectively bought $100,000 from the exporter and added these to its dollar position. Depending on the circumstances, the bank can now do one of two things with these recently bought dollars. If there is a pending import payment of an equivalent or larger amount, it will use the amount from the export transaction (inflow) to pay for the import payment of another client (outflow). This means the bank will sell the $100,000 to its client, say a chocolate importer at the interbank selling rate of Rs 305.5 and transmit the dollars to the country from which the chocolates were imported from.

However, if on that day the bank in question does not have any import payment to offset against the export proceeds, the bank will go to the ‘interbank market’ and sell the $100,000 to another bank at the interbank rate. This other bank will buy these dollars because it needs to make an import payment but does not have enough dollars of its own. The reason banks will typically sell this amount to other banks, rather than keep it on their books, is because the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) does not allow banks to do this unless they absolutely have to.

Think of it like this: there is a minimum limit that a bank must have on its foreign exchange book. Anything above that has to be justified; otherwise it should be sold in the interbank. Anything below that and the bank has to go and buy from the interbank to cover the shortfall. Such transactions determine the ‘interbank exchange rate’.

There can be other variations of this. Perhaps a bank has to make a larger import payment for oil of around $1 million. Now, in a market such as ours where dollars are usually in short supply, the interbank foreign exchange desk will start buying dollars in batches in advance, before the payment date.

The bank’s treasury will inform the SBP that there is a pending oil payment for which buying of dollars is being done daily and nothing is being sold back into the interbank market because there is a requirement of $1 million. During such instances the interbank rate tends to go up since supply is being removed from the market.

Major inflows in the interbank market include export proceeds, home remittances, dollar encashments at branches and Foreign Direct Investments (FDI). Major outflows include import payments, outward remittances, profit repatriation of foreign companies and any payments and fees to be paid to foreign companies selling in Pakistan (think payments to Amazon, Netflix and Google or Airlines).

A combination of all these inflows (supply) and outflows (demand) takes place on a daily basis and banks along with the SBP and of late the Finance Ministry do a delicate dance of managing these various transactions to keep the interbank market and the exchange rate generated by the activity in it, in check.

Banks are heavily regulated and treasuries cannot play outside the parameters set by the regulator. They do as they are told; you can’t make money in banking if the regulator is consistently unhappy with you.

Open Market – The rowdy rebellious one

The open market comprises exchange companies (EC) who partake in trading of foreign currencies. The major inflow into the open market is through ‘inward home remittances’ that are transferred by expatriate Pakistanis to foreign currency (FC) accounts that are held by ECs in domestic banks. The other inflow is individuals selling foreign currencies to exchange companies at their brick and mortar locations across the country. These could be travellers coming to Pakistan from abroad etc.

Exchange companies fall into two categories. Those in category A have higher minimum capital requirements of Rs 20 crore and can perform a broader range of functions. Exchange companies in category B have lower minimum capital requirements of Rs 2.5 crore and can only act as money changers.

However, after the recent crackdown, the SBP has ordered all exchange companies to consolidate into a single category with a minimum capital requirement of Rs 50 crore.

One outflow of dollars from ECs is the demand for dollars for physical currency by individual buyers. However, there are many restrictions on the demand side of this market. More on this later.

ECs are also allowed to make outward remittances but only to personal accounts of individuals i.e. personal financial transactions and not those related to an individual’s trade or business requirements. The volume of these transactions cannot exceed 75% of the inward remittance business. Volumes are usually quite low in this regard.

Additionally, there is the option of exporting physical foreign currency, with a restriction on US dollars. This too would therefore not account for any major outflow.

The open market is a much simpler operation than the interbank with much lower volumes with simpler transactions. Theoretically speaking it isn’t big enough to have a major effect on the economy from a fundamentals point of view. An individual buying $20,000 of physical currency from an EC or someone remitting the same to Pakistan is not going to have an effect on inflation or the current account deficit.

Why all the fuss then?

Mind the gap

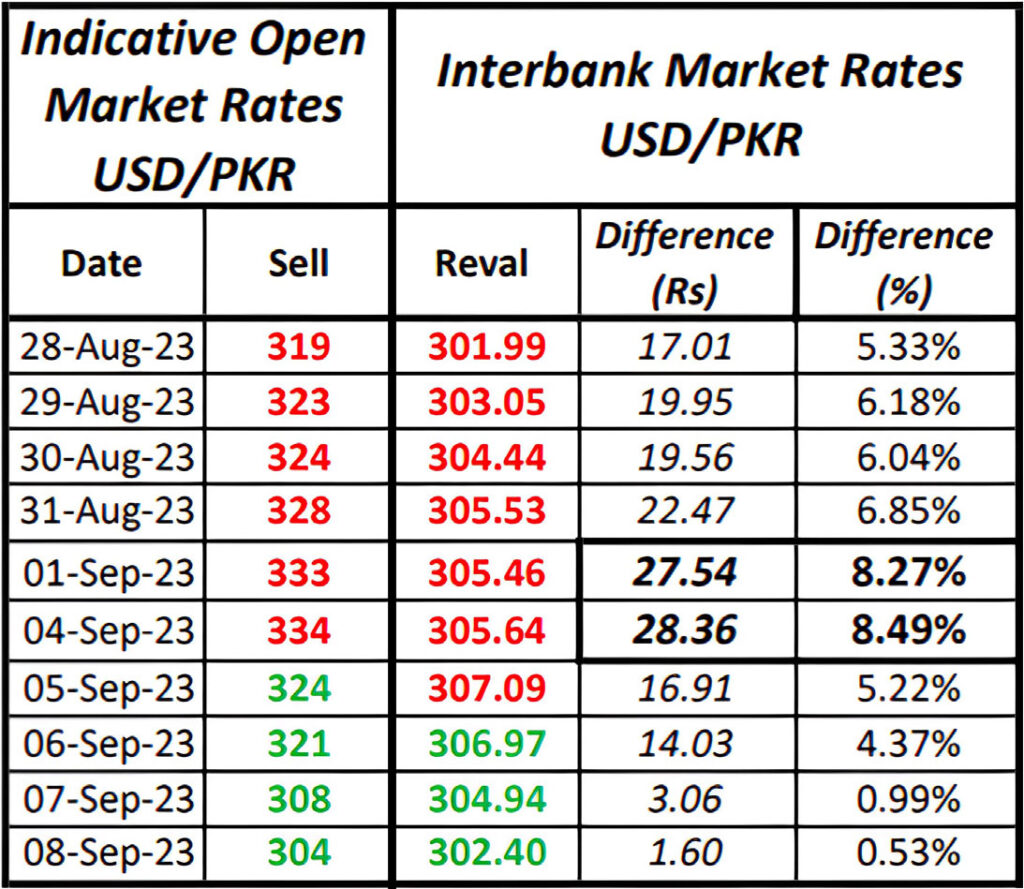

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), under the ongoing US$3 billion Stand-By Arrangement requires Pakistan, among various other conditions, to maintain the gap between the interbank and open market rates at maximum 1.25%. The idea behind this condition is simple. IMF suspects that SBP in the past has been coercing the banks into keeping the dollar rate artificially low in the interbank market. IMF does not like this, as this encourages imports and discourages exports, making the dollar reserve situation even worse . IMF, it seems, also believes that the open market is much more difficult to coerce and by requiring the rates in the two markets to be close to each other, it was hoping to keep the interbank rate nearer to the market reality.

But not only was this condition not being met, the delta was so high that even if the IMF was not making us do it, such a wide gap was abnormal. The chart below clearly shows that the open market and the exchange companies that are its main drivers had gone berserk.

It shows the difference in the selling rate of the open market and revaluation rate (average rate in the interbank market after each day’s end of trade) in both absolute and percentage terms.

The interbank market was clearly less volatile than the open market. It is more heavily regulated and compliant. The open market on the other hand was exploding because it wasn’t being looked at with the same level of oversight.

The 1st and 4th of September are days when the gap widened to levels that were enough to warrant immediate action. Something had to be done. One option was for SBP to remove or at least relax the import curbs from the interbank market and let the dollar rate increase to around Rs 330 in the interbank as well. The other was to somehow bring down the open market rate. The second option was politically ideal. But how to do it? If SBP could do the job, it would have done it by now.

So in the days that followed, ‘Big Brother’ stepped in. And the rate in the open market was brought down to below the IMF-stipulated limit, where it remains at time of writing.

But how was it done exactly? Three major measures were taken.

Off the books dealings

How does the dollar rate in the open market go from Rs 319 to Rs 334 in a matter of 6 days? In short, ‘off-the book’ trades, a parallel market being run by ECs. Something that can only happen in the open market.

As per the SBP, individuals looking to purchase more than $500 have to present a valid visa, passport, airline ticket, biometric to prove they are buying dollars for travel purposes. They also have to pay for these dollars from their bank account into the EC’s bank account. If one fulfils all these requirements, they can buy their requisite amount and get an official receipt of the purchase. But what if one does not fulfil the requirements and still wants the dollars really bad?

Profit spoke to multiple ECs in Lahore to understand what has been happening. Let’s go through this step by step; here’s a hypothetical that most likely happened, multiple times across the country.

An individual with a demand for $10,000 cash walks into an EC’s branch. He has the rupees to make the purchase but not the requisite documents. The person at the counter where the rate is displayed on a screen as Buy/ Sell, 315/318, says they cannot entertain his request. The buyer says he is willing to pay a premium. The person at the counter directs him to his ‘manager’, sitting in the back.

The manager offers to sell the $10,000 at a rate of Rs 328, Rs 10 above the prevalent open market sell rate. The deal is done. But apart from the rate, another major difference is that this transaction is not noted in the ECs formal ledger that is declared to the SBP, rather a parallel one that is maintained for transactions done on cash and without any official receipt: off-the-books.

So how does this push the rate upwards? That’s the technical bit.

Once the EC has sold an amount of $10,000 at Rs 328 while the market is at 315/318, he has created enough room between the rate at which he is buying currency, Rs 315 and the rate at which the unofficial sale has taken place 328, that is Rs 13, to earn a higher spread.

Later, another customer, looking to sell $10,000 goes to the same EC. The rate displayed on the counter is still 315/318, but the seller would want to get the maximum rate possible. What does the EC do? Now that he has that Rs 13 room, he can buy the $10,000 from the new customer at a higher rate so that he doesn’t lose this business. So, he offers to buy the amount at Rs 317, Rs 2 higher than the prevailing buying rate of Rs 315. This transaction will be recorded on the formal ledger that is reported to the SBP and the seller will get an official receipt as well.

The SBP requires ECs to maintain a maximum 1% spread, i.e. the difference between buying and selling rates, which works out to roughly Rs 3 currently. So once the EC has bought $10,000 at Rs 317, in order to maintain that 1% spread, his official selling rate now goes up to 320.

In short, that unofficial off-the-books Rs 328 selling rate at which the first customer bought $ 10,000 pushed the official rate from Rs 318 to Rs 320.

Now imagine hundreds of such transactions happening daily across all ECs. This is how you go from 319 to 334 in 6 days.

But how do you take it back to 304 in 4 days?

The first measure put in place was to stop this off-the-books parallel dealing of dollars. A coordinated operation was conducted against all ECs involved in this practice when the rate shot up to the 335 level. According to a number of ECs that Profit spoke with, who wished to remain anonymous for obvious reasons, officials from multiple agencies put in place strict monitoring measures such as placing men at certain EC branches while listening in on recorded lines as well.

This sent a clear message to ECs across the country, that the practice of off-the-books dealings would no longer be tolerated. Within the next few days, the market started to recede downwards, closer to the interbank rate, as only buyers who fulfilled the SBP criteria were being catered to at official market rates. Demand for investment purposes was eliminated. While some ECs may still be carrying out off-the-books transactions, they are far fewer and not enough to move the market upwards in any significant way.

“The reason that this operation has been so successful is that for the first time ‘agencies’ led the effort. Most of the raids were against category B ECs and some category A ECs as well. The rest of the market got the message loud and clear and stopped what they were doing,” explained the owner of an ECs in Lahore on condition of anonymity.

Moving dollars to the interbank

Last week Forex Association of Pakistan Chairman Malik Bostan said that ECs had ‘surrendered’ $20 million. This was the second measure that was taken, to move dollars from the open market into the interbank.This practice has been used before, but very sparingly. The last two instances were in 2019 and 2021, as per reports. There are essentially three ways in which this was done. In this case too, ECs were ‘made’ to do this as part of the larger effort to rein them in.

Cash

ECs surrender physical cash dollars to banks. These were probably the same off the books dollars that were bought by EC’s to sell at a higher rate. These amounts become part of the banks’ FX book and they are able to utilise these funds in the interbank. This way, there is an injection of fresh dollars into the interbank market.

Outward remittance

All ECs maintain FC accounts with domestic banks. They simply make outward remittances to banks’ FC accounts held with foreign banks. These accounts are called NOSTROs. Bank treasuries use these NOSTRO accounts to receive and make FC payments on behalf of their clients. What happens as a result is that banks get fresh funds that they can use in the interbank.

ECs FC accounts abroad

Instead of using FC accounts held with domestic banks, ECs use their FC accounts in foreign countries to transfer funds to banks’ NOSTRO accounts. The effect is the same as the outward remittance ECs make.

Smuggling goods, leaking dollars

Remember the ban on the opening of L/Cs by the SBP to restrict imports? Banks would have to get prior approval before opening any fresh L/Cs. The practice continued for some time, starting in mid-2022 until January of 2023 when the SBP issued a circular that it had lifted the ban on imports.

Since then, as per multiple commercial bank treasury officials and corporate bankers, the SBP has verbally said that it had ‘taken back’ that particular circular and banks would have to use their ‘cautious discretion’ when opening L/Cs.

But wait. How are imported items still making their way to grocery stores? In fact, even when the ban was in full swing unlike now, you may have noticed that there wasn’t really a severe shortage of your favourite imported items.

What was going on? In short, smuggling.

Officially speaking, Afghanistan uses Pakistan as a transit route to import items for its own use. Here’s how it happens, or at least is supposed to happen.

An importer in Afghanistan places an order with a Chinese company for printing inks. The importer makes an ‘advance payment’ to the Chinese company. The goods will be shipped to Karachi port by the Chinese company from where a trucker, with the proper paperwork showing that the goods are bought and paid for by the Afghani importer, will drive the goods across the Pak-Afghan border to the owner of the goods in Afghanistan.

Naturally, no duty is charged to the Afghani importer since the goods aren’t meant for Pakistan.

But what is actually happening here is much different. The printing inks are not meant for Afghanistan at all. In fact, there is little to no demand for these inks in Afghanistan as they don’t have a lot of printing presses there; the goods are for the Pakistani market.

Once the inks arrive in Afghanistan, they will make their way back into Pakistan through the same Pak-Afghan border. This naturally requires on-ground ‘help and understanding’ which is easily bought. (Editor’s note: Due to the current state of freedoms in Pakistan, we are unable to state the name of the government agency whose officials man these borders) .When stopped for checking to assess duty charges, the trucker bringing the inks back into Pakistan says that it is coal or some other commodity on which duty is either exempted or is very minimal under the Afghanistan–Pakistan Transit Trade Agreement.

The actual importer of the inks in Pakistan now has to pay the Afghani who made the advance payment to the Chinese seller. This is done through ‘hawala/hundi’, the FC grey market, as it were.

The Pakistani importer will pay cash rupees, equivalent to the dollar amount payable to the Afghani at a rate much higher than the prevalent open market rate, to say an EC located somewhere in Peshawar as it is closer to the Pak-Afghan border. The hundi rate is higher as there is a premium for the service being provided.

Following this, the hawala/hundi facilitator will send physical dollars across any of the many weak spots along the porous Pak-Afghan border to settle the payment. These cash dollars are being sourced from the open market, which not only leads to supply problems but also leads to rate hikes (refer to the earlier example of an off-the-book trade).

The net effect of this sort of import, that should more accurately be described as smuggling, is that the Government of Pakistan misses out on much needed revenue from duties and taxes on imported goods. Additionally, precious dollars are leaking out of the open market into Afghanistan.

The third measure that has been taken is against the hawala/hundi companies operating across Peshawar who are partaking in this business of currency smuggling. The ‘danda’ has been used quite extensively there, if reports are to be believed. Simultaneously, the Pak-Torkham border was sealed shut as well, presumably to arrest the smuggling of goods.

Who does the importer turn to then?

So everything is hunky-dory now? Sadly, it is not that simple!

You see, Pakistani presses still need the printing inks and they will now go to their banks to import it for them, legally. As a result of the twin measures of cleaning up of hawala/hundi from Peshawar and sealing of the Torkham border; the demand for dollars to settle import payments will shift to the interbank, which will lead to increase in the dollar rate in the interbank market if supply is insufficient.

To that, add duties that were previously being circumvented and you have more expensive imports, because of the duties that will be paid on it. However, for that to happen, import curbs on banks will have to be lifted first. If there are no imports, there’s no pressure on the interbank and there are no duties being paid.

But as mentioned earlier, banks are still not allowed to open L/Cs with the fluidity and frequency that businesses want. This leaves importers in a tricky situation. Their banks still won’t facilitate imports and the Afghan option is good as done. This will lead to shortages of goods in the market. Businesses that depend on imports will start to close shop.

We have seen what the Afghan transit option is capable of doing to the currency market.

The demand for dollars in the open market

To sum up, there are three sorts of demand for US dollars in the open market. One; the buyer who has all the necessary verification to buy dollars from an EC to actually use for the purpose he is claiming, typically, travelling.

Second; the investor who wants to protect the value of his savings and perhaps also make a quick buck in the process when he sells the dollar he bought. This is the $10,000 customer who made the off-the-book transaction.

Third; the importer who is misusing the Pak-Afghan transit trade option needs to settle the payment. This leads to a demand for physical dollars in the open market by the hawala/hundi facilitating the transaction. In some cases, the hawala/hundi itself might be a small shady EC company operating out of Peshawar.

The latter two demands have been curbed. Bostan has claimed on record that the Pakistan Army on instruction of COAS Asim Munir has led the effort. Former Federal Minister for Water Resources also credited the army for the massive correction in the open market while appearing on a talk show with Wasim Badami, going as far as to say that the ISI chief planned and handled the execution of the plan.

One immediate effect of the closing of the gap between the interbank and open market is that individuals with dollar accounts with domestic banks will start encashing their dollars in banks rather than the open market. This will increase supply in the interbank leading to increased exchange rate stability.

Previously, when the gap was wide, these individuals would withdraw US dollars from their accounts through checks and sell those in the open market as the rate was higher. Now that the gap is negligible, it is more convenient to just sell to the bank.

What next?

Now that the problems within the open market have been addressed to satisfy the IMF, the only question on everyone’s mind, especially open market currency dealers, those heavily invested in cash dollars and the importer getting goods through Afghanistan, is, how long will this last?

These are afterall, administrative measures. It is regulation that has been done with force and conviction with zero leniency by an institution that is in no mood to play games anymore and has taken charge to ‘fix the economy’.

But at the same time, this is not some political party being taken apart. It is a market and the economy and one unignorable fact remains; if the market players do not believe that this new rate is the true reflection of the demand and supply dynamic in the market, they will be willing buyers eager to pay an extra Rs10-15 per dollar and the investors who had bought at a rate much higher than the current open market rate will continue to hold their position. This indicates a sentiment that the open market will rally once again and reach the 325-330 plus levels.

However, if the market stays where it is and remains relatively stable for 3 to 6 months, the dollar hoarders will perhaps be forced to cut their positions and sell dollars in the open market. The investor willing to pay a high premium will also vanish as his prospects to turn a profit will have diminished significantly.

Therefore, only time will tell which direction the currency market goes and how the players in this market behave.

Unfortunately, the larger picture is being ignored in all of this. The flaws and cracks in the fundamentals of our economy are being left unaddressed. There is no quick solution to our economic woes. Structural reforms are needed and sadly these are long-term in nature. But can the COAS control the markets till then with short-terms measures? Highly unlikely.

how is dubai hawala mkt different from Afghanistan mkt and why it has less impact on open mkt exchange rate??

No prospects of physical smuggling of goods or dollars. These two contribute to big transactions. Small amounts can’t affect the market that much.

Can we make it more bureaucratic for Afghan importers to import goods via Karachi? Make them submit proofs that they need the imported goods (like list of printing presses that need inks) and keep a ledger to identify the misuse?

In this day and age, how hard it is to create a system that keeps track of all this?

If we make it a proper administrative procedures with digitalization and checks then they will have to look to other places to do their illicit trade like Iran.

Why even allow trade with Afghanistan. Rulers should curb the Afghan border and rather open the Indian border. Much more free and easy to handle.

An educational and interesting read

I think one workable solution will be to incentivize dollar inflows by letting Pakistani Banks to offer Eurobonds to local investors. Why is RDA schme restricted to non-resident Pakistani’s. I bet lot’s of dollar under the matresses or safes in people’s houses will appear magically.

Why is there even a border between two Muslim countries??? Remove the border drwawn by colonialists. When same currency in whole Europe can work for them.. why can’t we make Afghanistan and Pakistan just two provinces of an Islamic State..?

imports are curved but at what cost.

Excellent article which puts the entire issue of Green Back money issues in Pakistan in perspective. Let us hope that these short term measures leave lasting effects.

Excellent article Yousaf. This examples-loaded article presents the real picture in an easy-to-understand way.

Thanks Profit, we know now how the FCY mechanisms work.

But question is, why not the showbazs let market settle at any rate when it is not possible for buyer or seller to make anymore transactions due to high rate or FC cash drying up in pubic. That equilibrium was the objective of IMF which again PR hungry people ruined whereas market will one day again go back to the natural rate or even higher commensurating performance of economy of Pakistan which is the real thing to be fixed with long term hard work?

An excellent read. Thanks for explaining everything in a comprehensive way.

An ex bureaucrat currenty residing in west accused the authorities of using afghan transit as a ruse for importing goods in pakistan. Seems like he was telling the truth afterall. Maybe the entire pond is dirty and only one fish wasn’t and it paid for it.

Brilliant exposure of the facts & overall process . Seems like either no one really wants to fix the issues or isn’t allowed to do so – including IMF (which itself is a politically motivated institution). Government servents, Pakistani/Afghani Businessmen (mafias) as well as official from security agencies have huge involvements in this mess. A simple/short-term crackdown is just a show being put on to present that there is a “Will” to fix this situation but with past (such) adventures it is expected (again) to just become a political/authority stint.

it is a comprehensive, worthwhile and uncomplicated piece of writing. I was unable to understand this whole phenomenon for several years. But thanks to you now I can understand this whole thing.

Well there is no debate on the parallel economy that feeds hawala system ( the backbone of trade ) being a money exchanger i personally condemn the smuggling but the writer hasn’t developed sense with respect to the actual ground realities ( cross border movement , speculation , FC reserve pressure )

Mafia has engulfed the whole system it’s not just bureaucratic thing @muneeb

Allowing pakistanis access to RDA accounts would increase the USD holding in private banks. Also encourage and incentivize folks to buy and keep USD through banks.

If the smuggling has been cut down, and banks are limited on L/C, how are imports being done now?