Ever wondered why some fabrics feel smooth as silk to touch while others are abrasive against one’s skin? Ever chose a dress that looks stunning on the body but feels like you’re wearing a wire mesh? Or, despite being hailed as one of the best in the world, have you ever wondered why Pakistan’s cotton isn’t all that popular internationally?

Conversing with Profit, Adeel Khalid, Rang Rasiya’s Managing Director, shares his credible insight while commenting on these prickly questions as well as the rag industry and trade overall.

With his freshly acquired degree in Textile Technology from North Carolina State University, Adeel was in 2008 a third generation entrant into the family business – thinking that he was best equipped to carve out greater success than his father and grandfather, who had stepped into textiles by setting up a hand-printing mill in 1974.

Adeel was in for a rude shock.

“On returning back home, I was convinced that our edge was in thicker thread – known as the coarser count – of 8, 10 and 12,” said Adeel.

[For the uninitiated, thread count means the number of threads woven together in a square inch. It’s counted both lengthwise, called warp threads, and widthwise, called weft threads. The higher the thread count, the higher the quality of fabric and the smoother the finish].

“We make the best fabrics in 10 counts, making us good in socks and towels. I was interested in that and I had seen firsthand the huge demand for these products in the US.”

His father advised against it, but determined to prove his point Adeel invested with his maternal uncle in his Five Star Textiles, producing luxury towels. Unwilling to accept failure, he is still convinced that he may have succeeded if it wasn’t for the export crisis hitting Pakistan in 2008-10.

“India beat us by a great deal back then too. Their government assisted [the industry] but we had many issues here. So, in 2011, I had to shut it down. It did not help that my preferred customer JC Penney was only buying from India. So I was left with only Walmart. JC Penney’s is at the high-end, with many in between that and Walmart. Walmart has a limitation: it sells basic category towels and 90 percent of these are made in Pakistan.

“There was 40-50% cost differential. If we were selling at $4-5 per kg, JC Penney was buying it at $7 per kg from India – having an entire industry behind it, with superior technology in weaving and dyeing.”

Eventually, Adeel gave up and decided to move to lawn business – “to fulfill my ambition in value. My family business is in printing, making commodity lawn, sold at Rs70-80 per meter. But I decided to launch my own lawn brand.”

Reminiscing about titling his brand, Adeel noted, “My wife and I came up with two options Rangrez and Rang Rasiya. I chose Rang Rasiya. A couple of months later, my friend Haroon Hasaan told me, he had chosen Rang Rasiya for his brand. I told him I have already registered it. In the same instant, he said, then he’ll go with Rangrez.”

Starting up with Standard Textile Mills in 2011, he said, “My aspiration was to provide a high-end option through investing immensely in research and development of contemporary clothing for Pakistani women. We produce exquisite apparels using standardized fabric, further embellished with modern accessories.”

His drive stems from “need and passion”. People are going to continue to need clothes, said he, adding, and, “My passion is to provide fashion – updated high-street fashion with value and luxury – at a reasonable price.”

The edge is in finesse

At the end of the day, he reckons, the game in this industry ends up on the ‘designs’. “You can hire a chef for Rs20,000 or for Rs200,000. All the difference is just in the finesse. There are so many designers out there, everyone, every brand, is into designing these days. The edge is in the finesse, which must reflect in each and every piece you put in the market. If you put out 20 designs, every single one ought to show effort and hard work.”

Seeing someone else wearing the exact same outfit as themselves cheeses off Pakistani women – a tendency many high-end brands eschew by maintaining ‘the exclusivity factor’ through producing a design in limited numbers and then shortly discarding it for good.

So, keeping a high focus on design quality and managing people’s penchant for exclusivity is a drain on the cost-effectiveness of a brand.

“It is only about the numbers. If we consider the number of clothes per design, we reduce the number of potential customers out there, the result is 0.12 approximately. The number of units we or anybody makes in one design is very low to the proportion of customers, so that is not a major problem. Even if I make a thousand pieces in one design, that as compared to the customers is extremely low but it serves the purpose of keeping designs exclusive.”

Continuing on the issue of cost-effectiveness, he elaborates, “The innovations in the digital printing methods have been immensely helpful. It’s just like a computer printer: you give a command and a thousand shirts are printed in an hour.”

Digital printing is more expensive than conventional printing for now but it has several advantages, most important being no limit on colors in a single design. If a flower has hundreds of hues, one can have them all. “Going back to my grandfather’s time there were one-color designs, then two-color, and then for 20 good years only four-color. Even today several printers are working on a four-color palette. But now that limitation has ended.”

To him, lower-cost alternatives are no threat if the accent is on design. “The design is of huge value. The new brands can attract customers on lower prices only for so long. But the creativity cannot be compromised upon. For example, when Limelight or Agha Noor entered the market, Sana Safinaz ensembles may have lost a proportion of their market but their customers remained.”

The importance of design

Pick up the top few design colleges in Pakistan and you have 1,200 graduates every year. “But there might be a hundred at most who are actually good. There is a natural talent and then there is the hunger to become better. I always tell my team to go for the hunger of being able to put something out there that no one else is doing.” The importance of design, he noted, has been there forever, but customers have consciousness towards this has developed recently. Now, it’s importance is overwhelming.

“The fabric is almost similar all around, everybody has perfected their fabrics, 90% of fabrics, dupattas and embroidery are the same. The flow of information is so fast that a single picture put up on social media tells all about the makeup artist, the photographer, the designer and the clothing brand. In times bygone, designers did not use to allow photographs of their work, now they share close-ups. Because now designers know that even if they are copied, the name stays, for the copies are sold as copies of the brand. If someone cannot afford the Rs6,000 suit and buys a Rs600 copy, even he/she will aware of who the original designer and the brand were.”

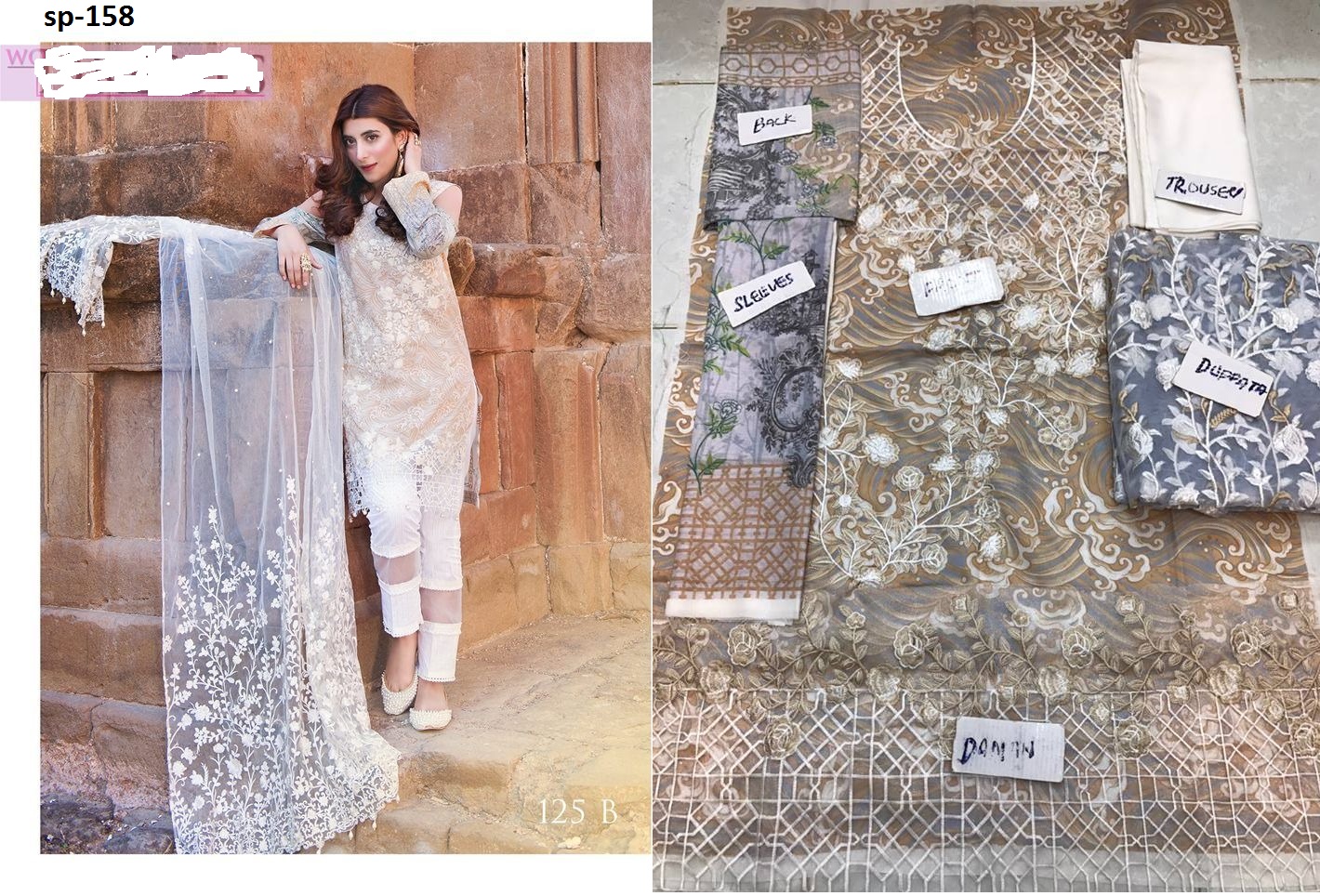

Talking about his own products, Adeel informed, “We retail in price band from Rs2595 to Rs6500, and this involves four-piece embroidered unstitched range. Our basic fabric is almost the same in all our products because we don’t use substandard quality in any product. The price difference comes from other factors. For instance, in a Rs 6,500 dress, we use pure silk dupatta, which alone is worth Rs2000. That is a luxury not available in lower-priced items. Then the quantity of embroidery and designing, and overall layout of the piece forms the price difference.”

As of now, he is not in it, but he shares the sentiment of many retail establishments about its decline whom Profit has spoken to. Perhaps that’s why his plans to enter retail are set 3-5 years from now. “In crisis for a while now, the sector isn’t doing well in Pakistan.” Sharing his expansion plans he said, “We shall introduce our Pret range exclusively on outlets and not online so that buyers could have a feel of the texture prior to the purchase.”

Our cotton, not such a rage on world stage

Moving onto the world markets and Pakistan’s share there, Adeel explained why Pakistan’s cotton isn’t very popular internationally. “The best cotton isn’t from Pakistan. It’s from India or Egypt. The thing is that longer the size of the fiber, the finer it is. Think of this as a regular rope. If you cut it into very small pieces and then join it, it will give a coarser feel because the ends will be protruding outwards giving a rough finish. We are best in the range of 8 to 12 count but they are best above 30. We don’t even get close to them [in sheer quality]. Their cotton is extremely fine. Egypt itself produces longer thread. Then their technology is also better.”

The comparisons on fabric, said Adeel, are made worldwide on the price range in different thread counts. There is no comparison between a 20 and a 60 thread count, rather how pricey the product is in a particular count.

“Below 20 Pakistan is the best because we are the cheapest in that count. In quality, they are much better but they are also expensive and it takes them higher cost and more time to produce it. We also produce 30, 40, and 50 thread count fabrics but in that category, we are more expensive than them. Count 60 and above is beyond our range and production capacity.”

About the final finish, Adeel added, thread count and length are not the only determinants. “Quality of yarn is one thing, and every mill has a different quality. But then processing may be different as well. The mills with a better finish will have a softer, more expensive end-product.

So, if a particular retailer has both coarse and smooth types of denims, for instance, he might have gotten the finer ones processed from Turkey, and the coarser ones processed from Bangladesh or Pakistan.”

Then there are instances when a coarser fabric is produced by choice – to cater to consumer tastes. That is why brands like Levis and Armani sometimes display jeans and types of denim that feel like hardened paint against the skin. “Sometimes we provide amazing finish but the customers don’t like it. That necessitates treating clothes after production to make them conform to prevalent tastes, irrespective of fabric quality.”

How and where we lost it

How over the years Pakistan lost its major share in cotton exports in world markets? “The cost of production in Pakistan depends on individual products. We were competitive in under-30 count category internationally. Then China developed microfiber and started mass production about 10-12 years ago. Those here specializing in the coarser bedding, such as T150, T128, used to purchase it at a lower cost. They went towards microfiber. China was producing it with 100% polyester, while we were still in poly-cotton mix production. So, China took a major share from us. When we tried to overcome that by going into higher-thread counts, China and India were already major competitors there. In terms of clothing that didn’t translate locally, because women here don’t only concern themselves with the fabric but also with how it looks. But in bedding sector even locally it has affected us massively.”

Adeel also blames the government policies, or the lack thereof, for the unrelenting increase in local competition and the ever-decreasing competitiveness of Pakistan’s textiles in the world markets.

“Pakistan has always been under pressure in the international market. The policy-instability in successive governments and the fact that the government has never been very supportive of the textile industry has taken its toll. Second, because there is no policy and therefore no barrier to entry – now the case in almost every industry in Pakistan – the inner competition is high. But if you compare it with the world, India or China etc., certain policies are governing the industry. Owing to the absence of governance, the inner problems in the local industry also become pronounced to the world. If for example, there is a devaluation in the prices in the local economy, it is immediately passed on to the foreign market even before anyone has the time to digest it. The brands start to provide discounts and other incentives to secure orders, devalued their products.”

Such an amazing article with so much detail loved the way how precisely you mentioned each and every fabric.

Comments are closed.