Allied Bank is the type of institution that makes that “Lazy Big Five Banks” stereotype look true. The bank has been – almost without interruption – the fifth largest in Pakistan for the last four decades and it appears perfectly comfortable staying there. While the bank has among the cheapest deposit bases in the industry, it has grown slower than the industry as a whole over the last five years (a compound annualised growth rate of 10.1% versus 12.1% for the industry).

On the surface, the bank’s strategy for profitability has largely relied on not rocking the boat too much and essentially adopting a “steady as it goes” approach towards both deposits and lending. Add in four management changes since its second privatization (well strictly speaking it was a recapitalization, more on that later) in 2004 and to many this might not look like a particularly good bet on the Pakistani banking sector.

But Allied Bank (ABL) offers much more than just the story of boring old big bank. The story of ABL is the story of banking in the country: the post-Partition era of competition, the Bhutto nationalisation debacle and its bailout-filled aftermath, and then the struggle to privatise. Much more than all of those, however, is a story that has implications for businesses in multiple sectors: how do you grow a business that is already big, and already has a dominant market share?

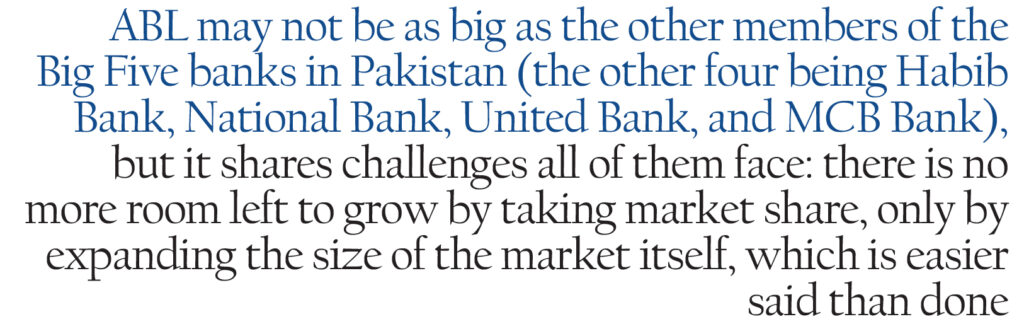

ABL may not be as big as the other members of the Big Five banks in Pakistan (the other four being Habib Bank, National Bank, United Bank, and MCB Bank), but it shares challenges all of them face: there is no more room left to grow by taking market share, only by expanding the size of the market itself, which is easier said than done.

History of the bank

Allied Bank has quite possibly the most interesting history among the Big Five Pakistani banks. It started its existence in 1942 in Lahore as Australasia Bank, founded by a silk trader named Khawaja Bashir Bux.

Bux’s father, a Kashmiri man who was born and raised in Lahore, was orphaned at an early age and was raised by his grandmother. His family were silk weavers so he knew the family trade from an early age. In the 1880s (the precise year is unknown), he traveled to Bombay and began working on ships with silk traders. He went on several voyages to Somalia and Singapore before finally making it to Perth in Australia.

The elder Bux appears to have had taken a liking to Perth and decided to settle down there, continuing to offer silk wares to the Australian market, building himself a small fortune in the process. His business and family allowed him to stay connected to Lahore, however.

His son Bashir was born in 1911 and appears to have joined his father’s business from an early age. However, by 1942, young Bashir’s ambitions led him away from the family trade and into banking, and he started the Australasia Bank in Lahore with Rs120,000 given to him by his father.

Partition was good for Australasia Bank, when the main banks serving the Pakistani side of Punjab – primarily the State Bank of India and the Punjab National Bank – closed shop and left. The bank continued to grow right up until 1974, when the leftist Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s administration nationalized all banks in Pakistan.

Australasia Bank was small back then, with a presence largely confined to Punjab. So, in addition to nationalizing the bank, the government also merged it with Sarhad Bank, Lahore Commercial Bank, and Pakistan Bank, making it one of the five large nationalized commercial banks (NCBs) in the country.

The nationalization era was the predictable disaster that one would expect it to be. By 1988, the five nationalized banks collectively cost the government of Pakistan 8.8% of the country’s GDP in what had by then become an annual tradition of bank bailouts.

When the center-right Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N), led by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, first came to power in 1990, bank privatization was high on their agenda. Within weeks they had privatized Muslim Commercial Bank (now MCB Bank), selling it off to a consortium led by industrialist Mian Muhammad Mansha. Allied Bank was also put on the auction block but was bought by its employees.

The year 1991 seems to have been marked by employee buyouts. Exxon Pakistan’s employees had bought out their US parent’s stake in the nation’s second largest fertilizer manufacturer. Many populists felt that Allied Bank’s management buyout would be no different, resulting in an employee-owned bank that would be profitable and no longer a headache for the government. That assessment proved to be disastrously shortsighted as Allied Bank became the only Pakistani bank to have to be privatized twice.

The key difference between the Exxon management buyout and the one at Allied Bank was that the Exxon employees had always been part of a private sector organization, one that was accustomed to running at American levels of corporate efficiency. Allied Bank was the child of populist nationalization, and was more used to giving out loans on personal whims or possibly political connections rather than any real credit analysis.

While MCB Bank cleaned up its balance sheet and became a financially healthy institution, ABL lagged behind, showing no real improvement in its operations and continuing to lose money almost at the same rate as when the government was a majority shareholder.

Non-performing loans were at 16% of the loan book when the management buyout was completed in 1993. They hit a record 36% a decade later, in 2003. The first two post-privatisation CEOs of the bank ended their tenures by being sentenced to prison on corruption charges. (And this was in the 1990s. To get caught and jailed for corruption, you had to be really corrupt.)

In 1999, one of the bank’s largest clients (newspapers from the time refuse to say who and current bankers claim not to remember) borrowed heavily from the bank to buy a 35% stake in ABL itself, and then defaulted on those loans (a real genius, this one must have been). At that time, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) – still a 49% shareholder in the bank – stepped in and froze share transfers from existing employees to outside shareholders.

By that time, the Musharraf Administration had come into office and appointed Dr Ishrat Hussain, a Boston University-trained economist at the helm of the central bank. Hussain determined that Allied Bank’s first privatization was not enough and that the bank needed to be sold again.

Hence came the second privatization. But before that plan was set into motion, the government put in place a management team led by the highly capable Khalid Sherwani, a former United Bank (UBL) executive who had spent most of his career at UBL and had helped turn around that bank prior to its privatization at the turn of the century.

Sherwani has a fascinating background. The man is a chemist by training, graduating with a masters in analytical chemistry from the University of Karachi in 1966. He began his banking career in 1968 at the then-nascent UBL, starting off as a software developer (somewhat shocking that UBL had computers back then, let alone in-house software developers), became head of the IT department in 1974, and retained that position for 18 years. In 1992, he was promoted to senior executive vice president for finance and planning, and helped the bank’s management prepare UBL for its eventual privatization. However, before he could see that process through to the finish, Sherwani was hired as Allied Bank’s CEO in 2000.

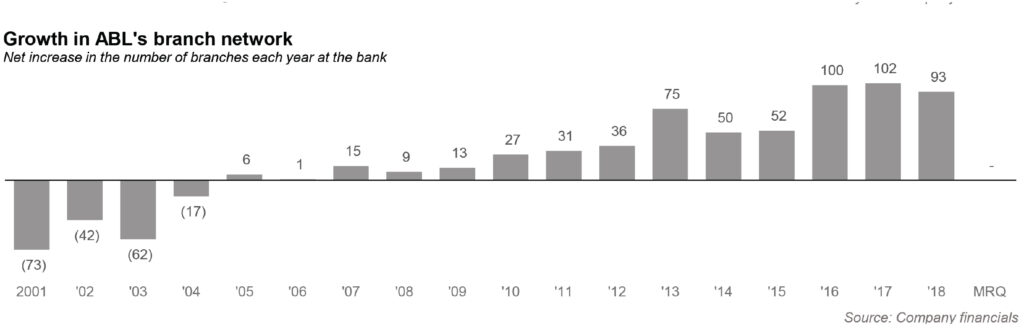

He immediately began a cost-cutting programme that saw the bank shut down 194 (~21%) of its lowest performing branches and lay off 2,228 employees (~25% of its workforce) over a span of four years. These actions were not in the least bit popular, but it helped that the economy was booming in Pakistan at the time and there were plenty of alternative employment to be found.

Sherwani’s new management was supplemented with changes at the board level as well. In August 2001, SBP Governor Dr Ishrat Hussain removed three board members, including the chairman, and put new people in place.

By February 2004, the Allied Bank was stable enough for both the government and the SBP to feel comfortable putting it on the auction block. ABL’s balance sheet, however, was in a terrible state. It was (and still is) the fifth largest bank in the country and had a non-performing loan infection ratio of 35.7% at the end of 2003. Anybody who bought the bank would have to inject a massive amount of capital into the bank.

Hence, a strategy different from its previous privatization transactions was devised: instead of selling its own shares, the government simply issued new shares, meaning that any buyer would be injecting every penny of their capital directly into the bank rather than paying the government anything.

Six parties submitted bids for the bank, with three going all the way to the final round: the military-owned Askari Bank, NIB Bank, and a textile and energy conglomerate called the Ibrahim Group. The bankers at Askari and NIB, despite all of their sophisticated knowledge of finance, ultimately thought the premium the government was demanding for the shares was too high. The Ibrahim Group was the only one that appears to have figured out that every rupee paid into the bank was a rupee saved on recapitalizing the bank. In the end, the other two bidders backed off and Ibrahim Group paid Rs14.4 billion ($237 million) to buy a 75% stake in Allied Bank.

Ibrahim Group takes over ABL: Industrialists decide to buy a bank, then leave it alone

Sheikh Mohammad Ibrahim was a cloth trader in Punjab when Partition happened in 1947 and he found himself caught on the wrong side of the newly created border. Like the more than 14 million other people in South Asia, Sheikh Ibrahim made the journey from the Hindu and Sikh dominated side of Punjab to what was about to become the Muslim-dominated side of Punjab.

In 1947, he took his family to what was then a relatively small city called Lyallpur (which would later be renamed Faisalabad) and re-established his trading business there, originally calling it Ibrahim Agencies. Ibrahim’s son Sheikh Mukhtar Ahmad joined the family business in the mid-1950s and began expanding the scope of the business rapidly, first expanding from cloth trading into yarn trading and then – in 1975 – into manufacturing yarn.

Sheikh Mukhtar’s business style can be characterized as one in pursuit of relentless growth. He had a habit of plowing back the bulk of the cash flows from his businesses back into growth, which is what appears to have set him apart from the thousands of other cloth and yarn traders who also started at roughly the same time in Faisalabad.

At first the group started off small-scale manufacturing. By 1980, they were able to set up a spinning mill called Ibrahim Textile Mills Ltd, with tens of thousands of spindles. In 1984, the group expanded to set up another unit called AA Textiles Ltd, and in 1990, set up a third unit called Zainab Textile Mills Ltd. To serve the energy needs of their rapidly growing textile empire, Sheikh Mukhtar set up a 32-megawatt power generation unit in 1991. By 1996, the group expanded into manufacturing polyester staple fibre, starting off with a capacity of 70,000 tons.

Between 2002 and 2003, Sheikh Mukhtar merged all of his other textile units (and the power plant) under the Ibrahim Fibres umbrella. In 2004, the group was able to complete a capital investment project in Ibrahim Fibres that tripled its polyester staple fibre production capacity.

By 2004, Sheikh Mukhtars’s son, Naeem Mukhtar, who had been helping with the family’s business since having graduated from a business school in the UK in 1992, began taking over more of his father’s responsibilities. Indeed, it was Naeem who led the group’s bid for ABL and subsequently became its chairman.

While the Ibrahim Group has largely focused on textiles for almost the entirety of their existence, they were not alien to the financial services sector. In 1992, the company established a leasing company and in 1995 established a modaraba (an Islamic investment vehicle). The two companies were merged in June 2001 to meet minimum capital requirements instituted by the central bank for leasing companies.

In 2004, when the Ibrahim Group took over Allied Bank, Ibrahim Leasing was merged into the bank to form a single financial services entity owned by the conglomerate.

Despite his success in business, however, the Mukhtar family appear to know the limits of their own abilities. Naeem could see that Khalid Sherwani had done a good job in turning around the bank and so he asked the CEO to stay on.

Sherwani stays on: After the cost-cutting, the consolidation

Sherwani was only too happy to stay on at Allied Bank, given the fact that he would then be given the chance to build upon his success as a turnaround architect. From contracting the branch network, by eliminating the unprofitable branches, he could begin expanding. And he could also use the newfound financial strength of the bank to expand into other avenues of business within financial services, such as asset management.

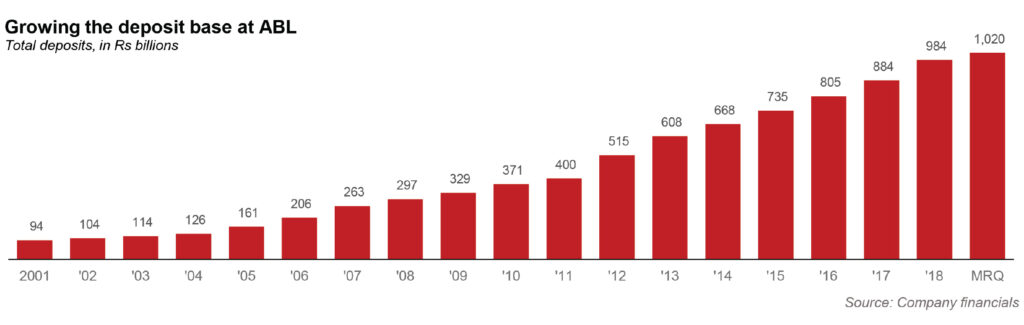

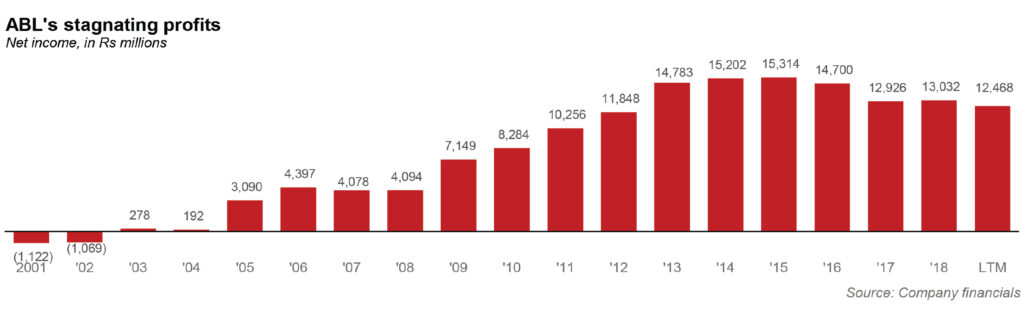

Sherwani’s tenure as CEO under the new sponsors was as successful as his time before them. Costs as a percentage of revenue kept declining every single year – and almost every single quarter – of his time as CEO. Deposits per branch, initially significantly below industry average, kept rising faster than the banking sector as a whole, and significantly closed the gap. Net income rose by an average of 14.8% per year between 2005 and 2007 to reach Rs4.1 billion ($67.1 million). Between the recapitalization in 2004 and the time Sherwani left towards the end of 2007, deposits grew by an average of 27.8% to Rs263 billion ($4.3 billion).

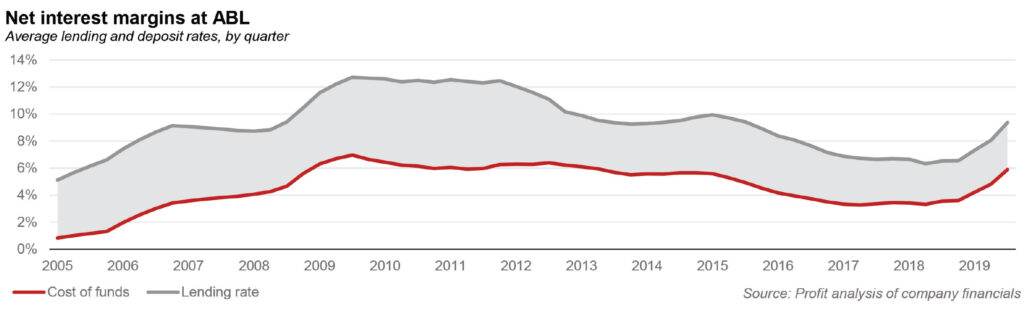

However, that record was helped by three key factors, only one of which was attributable directly to him: a rising interest rate environment coupled with an unusually depressed cost of deposits, the ability to take full advantage of Ibrahim Group’s good reputation by bringing in significant new deposits from the new owner’s friends and family in the Faisalabad business community and the payoff from having taken all the lumps on the non-performing loans prior to privatization. All these factors combined explain almost the entirety of the expansion in profitability at Allied Bank.

In other words, Sherwani was a good CEO, but his record is helped by the fact that he led the bank between 2004 and 2007, a time when virtually every financial institution on the planet was making piles of money. It is true, of course, that under the supervision of SBP he was able to right the ship at Allied Bank prior to 2004, a task at which all of his predecessors since 1974 had failed miserably.

He gave the bank a solid foundation on which to build success prior to 2004 and to make the bank ready for sale.

Perhaps it was an impeccable sense of timing, or perhaps sheer luck, but Sherwani chose to retire as CEO from ABL in October 2007, just a few months before all hell broke loose in the Pakistani and global financial markets. He left ABL with a record he could be proud of, though it was not the last time he would be at the helm of the bank.

Aftab Manzoor’s tenure: Stability, but not much else

If Sherwani had impeccable timing, his successor Aftab Manzoor could probably not have picked a worse time to take the job. His benchmark would be 2007, the best pre-crisis year. And his tenure would be marked by the worst financial crisis in two generations. Of course, he had no way of knowing any of this when he took the job in November 2007.

Manzoor had spent the bulk of his career at Citibank in Pakistan. In 1998, he had joined MCB Bank as head of credit and risk management. In 2000, he was promoted to CEO, a position he held until 2007, when he moved to Allied Bank.

Considering the time he arrived at the bank, Manzoor’s record is nothing short of stunning. Between the end of 2007 and the middle of 2010, a time of immense difficulty in the financial services sector, he managed to grow profitability by an average of 29.3% per year (in rupee terms) to Rs7.7 billion ($92.6 million). And he did this by prudently expanding the asset book. At no point during his tenure as CEO did the non-performing loan ratio exceed 7.4% of all loans. Even a year after he left, the ratio did not exceed 8.2% of the total loan book.

Given the tumultuous time during which he presided over the bank, it is no wonder that Manzoor was cautious in growing the asset book. The size of the loan book grew at an annualized average pace of 14.1%, which sounds impressive until one considers the fact that inflation during this time was 14.2% per year, on average.

Still, keeping the bank stable and growing profitability at a time when most bank CEOs had their hair on fire is no mean feat. Yet, for reasons best known to Manzoor, he left Allied Bank in May 2010. He went on to head KASB Bank of all places, that disastrous balance sheet time bomb that made twice as many bad loans as good ones (that is not an exaggeration). Though he did leave KASB Bank within seven months for Soneri Bank.

Nonetheless, his departure meant that Sherwani got one last stint at the helm of Allied Bank.

Sherwani again: Sharp accounting to boost profitability

Sherwani, it seems is great for when you need to cut costs and stop the bleeding, but not when you need to grow the business. In June 2010, when he was called back from retirement, Sherwani had effectively been out of the game for three years. He would proceed to build up a record that looked better than it actually was.

The headline numbers were impressive. Between the second quarter of 2010 and the second quarter of 2013, a period almost exactly corresponding to Sherwani’s second stint at ABL, the bank’s assets grew by an annualized average of 16.5% and deposits by an even higher 17.4%. Book value grew by an average of nearly 23% per year. Even when accounting for the 10.7% inflation during this period, those are some seriously impressive numbers.

The problem arrives when you get to profitability, and there Sherwani’s record is less than stellar. Net income during this period rose by 11.3% per year, marginally above inflation. And these were the years when industry-wide net interest margins were expanding.

And this meagre record of profitability is despite the neat little accounting exercise that the ABL management used more than any other bank in the country. Until 2014, while the profits on regular banking business were taxable at a full 35%, a bank’s investment in mutual funds was exempt from taxation, meaning that the bank could make investments in mutual funds operated by its own asset management subsidiary and legally save money.

It’s a neat little maneuver that allowed for preferential tax treatment and ABL benefited from it more than any other bank. In fact, ABL was so brazen with it that the bank was specifically cited in the Senate Finance Committee as the biggest beneficiary of this tax provision because of which the law was later changed.

The change in this law, coupled with the new super tax on banks, had led to the effective tax rate of ABL going up from 26.5% in 2012 to 40.6% by the end of 2015. Return on equity had dropped to a still healthy 18.8% by the end of 2015, though down from 27.1% in 2012. Had the tax rate remained the same in 2015, that return on equity would have been around the 26% mark.

Tariq Mahmood takes the helm: Jovial number two takes the top spot

In June 2013, Sherwani decided to bow out of Allied Bank again, paving the way for Tariq Mahmood, the Chief of Banking Services Group, to become the new CEO.

Mahmood started his career in 1971 at Habib Bank, where he stayed for nine years. In 1980, he left to join a new Kenyan bank called the Middle East Bank. He worked at MEB for 12 years, joining Askari Bank in 1992, when it was formed. Mahmood stayed at Askari for 15 years, being promoted to senior executive vice president in 2003. In 2007, he was offered a spot at Allied Bank and he took it.

Under his watch, Mahmood supervised completion of Allied Bank’s shift to a better technology platform called Temenos 24. He also initiated the separation of the retail and commercial branches, in order to better focus the bank’s resources on the two different segments instead of trying to go after them with the same set of marketing staff which was later reversed during his own tenure.

Mahmood’s tenure as CEO was a modestly successful one. Net income was up by an average of 9.5% per year for the three and a half years that he was CEO. The asset book grew by 13.7% per year during the same period, though loan growth is only 6.9% per year. Deposits rose by an average of 10.4% at a time when inflation averaged 5.1% per year.

In terms of growth strategy, however, Mahmood and his team seemed to have trotted out the same tired old ideas that every banker in Pakistan talks about: trade finance, and Islamic banking.

ABL’s strategy to break away the best trade finance clients from the powerhouses at Habib Metro Bank and Bank AL Habib seemed unlikely to succeed. And as for the latter, ABL made a strategic decision to start its Islamic banking operations in 2014 by following the model of ‘bank within a bank’, instead of forming a full fledged separate islamic subsidiary. This decision was probably motivated by the biggest impediment to the growth of Islamic banking in Pakistan: a severe lack of Shariah compliant options to deploy funds.

In December 2016, Mahmood stepped aside to make way for his successor, Tahir Hassan Qureshi, who had served as the bank’s chief operating officer since 2015 and, before that, had been the bank’s CFO since 2008.

The current management: How to grow the already big

Qureshi faces an unenviable task: trying to grow a bank whose ownership seems interested in stability and low risk, and whose market position makes it difficult to make big moves. ABL commands a 7.3% share of total bank deposits in Pakistan, making it the fifth largest bank in the country in a highly concentrated market. The bank’s market share has fluctuated around that 7% market for virtually all of the last two decades.

So that then begs the question: how does one grow this bank that is already so big, with over Rs1 trillion in deposits and a balance sheet with Rs1.5 trillion in assets? How do any of the big banks grow at all?

For any business that reaches this stage, there are effectively two routes: grow market share through acquisition, or growth of the market itself. Both of those are easier said than done.

On the first route -– growth through acquisition – it has been somewhat slim pickings in the Pakistani banking market, until recently. The two most recent transactions involving banks being sold were both highly distressed sales: KASB Bank, and NIB Bank, former being considerably more distressed than the latter. However, ABL decided not to pursue either of these. The last time ABL showed interest in acquiring a bank was in 2012 when it’s request to conduct due diligence of HSBC’s Pakistan operations was turned down by SBP along with those made by HBL, UBL and MCB. The SBP had apparently used ‘too big to fail’ doctrine while rejecting these requests.

There are, of course, other banks that may go on the market, but based on ABL’s past experience and the post merger integration issues that usually come with an acquisition, it might not be easy for ABL to find the right fit. “For us the organic growth strategy has paid well, rather than acquiring a bank. There were few opportunities available for acquisition but we as a strategy would not look at those opportunities merely to enhance market share but also keep in mind synergies more closely associated with technologies and human resources,” said CEO ABL, Tahir Hassan Qureshi, without completely ruling out the possibility of an acquisition in the future.

That leaves the strategy of growing the market itself, which is a task usually left to either the market leader – in this case, Habib Bank – or to a disruptive player that brings about a new product line or a new way of doing business. In Pakistani banking, the last big innovation was the advent of Islamic banking, which Meezan Bank brought to the market in a big way and continues to remain the clear market leader in it.

As for growing the conventional banking market itself, that is an uphill battle. Over the past five years, ABL has opened 397 branches, growing its branch network by a whopping 42% filling the footprint gap that it had with its peer banks. That kind of growth in branch network should have yielded significantly higher deposits, but deposits per branch appear to have somewhat stagnated, meaning that the bank would probably have struggled to grow even as much as it has, had it not been as aggressive in opening up branches nationwide. Obviously, a slowing economy and the introduction of a withholding tax on bank transaction, factors outside the control of ABL, also had a role to play.

The next big phase appears to be the expansion of digital payments and banking the unbanked, two areas in which the banks face stiff competition not just from each other but also from well-financed technology giants such as China’s Alibaba, which bought out EasyPaisa, the largest digital payments platform in Pakistan, previously owned by Telenor.

If you are a bank in Pakistan, in other words, growth is hard to come by, especially if you are a bank like ABL, which is used to steady cash flows. The bank to its credit has paid out a dividend every single quarter since the fourth quarter of 2011, paying out like clockwork.

When asked what the bank’s core growth strategy would be, Tahir said in a somewhat restricted manner, “Since 2004, our numbers demonstrate a remarkable turnaround story. This journey of achieving sustainable growth will continue. Based on the board’s vision we are also pursuing a strategy of transforming ABL into a digital bank. With the lowest infection ratio and highest capital adequacy ratio (CAR) in the industry, the bank is consistently following a strategy to invest in human resource, technology and risk management systems.”

Ibrahim Group: And now, a word about our sponsor

By many accounts, the Ibrahim Group had a “clean start” meaning they seem to have earned their way into the upper echelons of Pakistan’s economic elite in a fair manner. Indeed, the family appears to take a considerable amount of pride in playing by the rules.

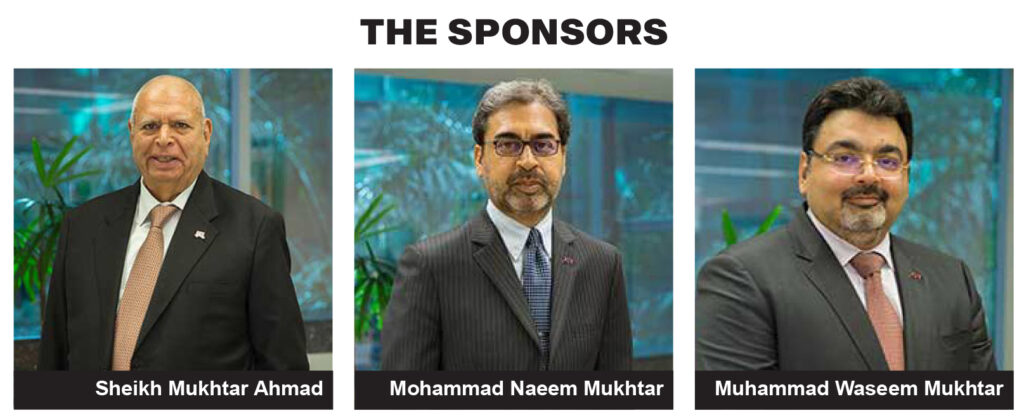

Sheikh Mukhtar and his two sons – Mohammad Naeem Mukhtar and Muhammad Waseem Mukhtar (both on the ABL board, with Naeem as chairman) – are three of the five highest-paying individual taxpayers in Pakistan. They have also collaborated with Syed Babar Ali in the creation of the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), easily Pakistan’s best university.

“They are an unusually professional group when it comes to Faisalabad. Most Faisalabad groups tend to be highly unprofessional when it comes to paying their vendors,” said one person who serves as a vendor to the group.

“These guys are almost always ahead of the curve. They dominate the market for polyester synthetic fibre with the highest quality product. You have to pay them advance deposit. They don’t like using old machinery and love upgrading to the best state of the art equipment available.”

“Not only do they pay their vendors on time, they also make it a point not to waste your time. They only generate inquiries when they are serious. When they just need information, they will tell you. When they want to buy, they will tell you. They have a stronger technical team than almost anyone else. They pay well, significantly above market.”

Naeem, who has run the family’s interest in ABL since the second privatisation, has had experience running some of the group’s other businesses as well. He has degrees in textile engineering and was intimately involved in that part of the group’s business, in addition to taking a keen interest in the mutual fund business, which operates through ABL Asset Management.

LIke his father, however, Naeem also appears to believe in the value of professional management. He knows the textile business and hence runs the textile company – Ibrahim Fibres – as its CEO. While being the chairman, he continues to have bankers run ABL, with succession planning within the organisation to ensure smooth transitions between CEOs.

But that non-seth attitude also means that a strong push for growth is unlikely to come from the board. And in light of the management’s strategy of “sustainable growth” and the cut throat competition in the digital space, it remains to be seen what ABL or for that matter any other member of the Big 5 club can do to increase its market share.

After years of wandering, today i read a beautiful article of yours.

Worth appreciating dear 🙂

A commendable dissection of Pakistan banking industry with particular reference to the growth of allied bank ltd starting from scratch, escalating to one among top five banks and the role it has played in the development of industrial sectors like textiles, polyester, energy and what not and also bringing professionalism in the banking industry.

Excellent piece, and beautifully researched.

Comments are closed.