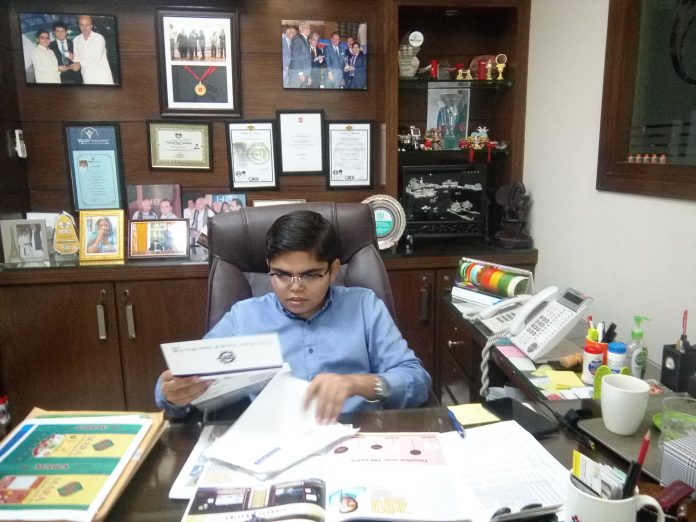

The decorations in his room contain awards, pictures taken with dignitaries recognizing him, souvenirs and sculptures of Hindu gods and goddesses. Designed in the fashion of a CEO’s office, the person behind the desk though is childlike features – perhaps owing to his ailment, thalassemia. This was Jatindar Kumar, known among his social circle Jatin Kewlani.

Every year International Organization of Standardization (ISO) Certified KK Group exports 200,000 tons of rice. Before Jatin, its Director Promotions, joined the company, it was exporting exactly half of that. This twofold increase catapulted the KK Group to third spot nationally amongst rice exporters in 2015-16, winning it the president of Pakistan’s award for prominent exporters.

Representing his company, Jatin has been to 20 countries for exhibitions. Travelling and working on his fitness in a gym are his favourite pastimes.

As we sat down for our little chat for Profit, one was uncomfortable – as one was bound to be, interviewing someone whose life-expectancy, one perceived, was not very long.

Not a disease, but a life condition

Jatin though was unfazed. “Thalassemia is not a disease. It’s a life condition… much like diabetes or blood pressure. Like those conditions, those suffering from thalassemia stay on drugs for life, with the addition of blood transfusion.”

To Jatin, blood transfusion is the same as change of lubricant in a vehicle once in a while. And medicine is like fuel that one has to top up with one’s tank every day. “If you take appropriate care with regularity, life goes on”, said he, with a maturity that not just belied his years but also reflected an attitude most admirable that spelt it out for you: Life has to be lived as normally as possible, regardless of the hand fate has dealt you.

At 16, a dropout after the sixth grade, Jatin joined the family business in 2005, looking after export documentation – at a salary of Rs10,000 per month, with his job description reading, assisting managers in the company.

Jatin is all praise for his father’s decision, which only provided a spur to his own dedication. “To garner success, you ought to be humble.”

In 2010, he was sent to the Gulf Food Exhibition. He must have done well, as from then onwards his father asked him to represent the company in all foreign exhibitions. Jatin has attended exhibitions in more than 20 countries including Anuga Food Fair in Germany, SIAL Food Fair in Paris and The Rice Traders conference in Hong Kong, Thailand and China.

“Owing to my childlike features, people are surprised at see me in those exhibitions,” says Jatin, who 5’2” height also makes him look far younger than he actually is. He has turned this drawback into an advantage. “I am kind of unique in these exhibitions… so people don’t forget me, and this has helped my company corner some buyers.”

Rags to riches

The CEO of KK Group, and his father, Chela Ram Kewlani came to Karachi in the early 1990s with only Rs10,000 that he had borrowed, starting up dealing in dates, before starting up with exporting rice.

When Jatin was asked about hurdles his father had faced for belonging to a minority, Jatin says, if you have a clean heart, the differences fade away. “My best friends are Muslim, and I like spending the better part of my quality time with them.”

Jatin has three brothers and a sister, all of whom live with an extended joint family of 33. At night, they dine on one table in two shifts, “as our table is not that much large to accommodate everyone at the same time.”

Jatin spends Rs200,000 every month for blood transfusion and other medical expenditure as part of his company’s Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) activities. Jatin’s ambition: “To take my company up the corporate ladder so that it could make a greater contribution towards CSR.” His other business objectives include, his company becoming the number one rice exporter from Pakistan and to turn it into a multinational.

“In Europe I have met an 80-year old grandmother suffering from thalassemia. So, if a patient in Pakistan could somehow land a good consultant and is administered appropriate medicine, he may live far longer,” said Jatin.

From blood transfusion to iron releasing tablets, the process requires Rs15,000 to Rs20,000 to manage the life of a thalassemic, and the government is only able to support 25 percent of total number of patients, increasing dependence on funds from Baitulmaal and other charities, said hematologist Dr Saqib Ansari.

The price of one pill that cost Rs230 has recently been jacked up by pharmaceutical companies by Rs50 a pop, adding on the financial burden on patients. As a consequence, the NGOs resort to smuggled stuff, but since this mode involves exposure to heat and sun, the efficacy of the medication is far diminished.

Non-affordability the biggest bugbear

Low income thalassemia patients who get blood transfusion through NGOs still have to spend Rs15,000 to Rs20,000 apiece each month.

And ‘Non-affordability’ is the biggest bugbear of thalassemia patients. After blood transfusion, iron has to discharge with the help of medicine; otherwise, it accumulates in vital organs such as heart, lungs and pancreas. And this iron overload can be fatal.

Thalassemia patients are also prone to receive diseases like hepatitis and HIV Aids due to ineffective blood screening.

Jatin realizes the situation for the poor is dire, so he has he has pitched in with a programme supporting 50 children.

According to the Thalassemia Federation of Pakistan, based on the last census, 10 million children have been diagnosed with thalassemia minor while 100,000 have been diagnosed with thalassemia major – in percentage terms, this is seven percent of the population. It means that nearly half a million infants every year are born with thalassemia major.

This data only counts cases in cities, as thalassemia experts don’t have means to ascertain the number of cases in hinterland. In cities children with thalassemia major have life expectancy of 15 to 25 years while in the boondocks it is reduced 10 years or thereabouts, said hematologist Dr Saqib Ansari who’s been running Omair Sana Foundation for thalassemia children for the last several years.

Resuming his studies, Jatin has just done away with his matriculation. Until he dropped out of sixth grade – his father pulling him out of school because he did not want to combat the incurable disease and be also cope with pressure of school and studies simultaneously – he was always top of the class.

“I recall teachers making several phone calls to my home, asking as to why why a top student had dropped out,” Jatin says.

More than his academic pursuits, to him, his travels abroad have contributed a lot to his learning curve. “If someone asks me about my academic qualifications, I make light of it, saying that I have done a PhD in thalassemia. People tend to believe me as I am able to answer every question related to the affliction. But the subsequent remark often is, being so young how could have I done my doctorate,” said Jetin.

Having attended seminars on thalassemia in developing countries, Jatin is flabbergasted when he goes to one in this country. “Once in a seminar organized by the Thalassemia Federation of Pakistan, a Sindh health minister, no less, had only this little piece of wisdom to contribute: ‘… it is a fatal disease and that the afflicted children need blood transfusion.’

Unfazed, Jatin runs his own thalassemia support programme, and his efforts have found recognition through many awards, including the Youth Achiever Award.

While Jatin is definitely an inspiring story, the darker side from a national point of view is that only 5 to 10 percent of children suffering from thalassemia in Pakistan survive beyond the age of 30. The government and society should come ahead to help and encourage patients and make measurement to prevent this grave disease.

For his part though, Jatin doesn’t consider thalassemia a disease; full of bravado, he says: “The day you feel disheartened and give in, even a non-fatal disease could kill you.”

BRAVO !!!

Keep shinning our Thalasseamic Star

Keep supporting your thal community

Motivational story for us and specially for Thalassemia patients…