In the 1968 Hollywood movie The Lion in Winter, King Henry II of England fears his three sons are plotting against him, and so he imprisons them for treason. As they sat in their prison cells, his sons fear that Henry will go so far as to sentence them to death. In one scene towards the end of the movie, the sons are locked in the dungeon, and think they hear their father approaching their cell, about to order their execution.

“He’s here. He’ll get no satisfaction out of me. He isn’t going to see me beg,” says Prince Richard (who would go on to become King Richard the Lionheart of England).

“My you chivalric fool… as if the way one fell down mattered,” says his brother, Prince Geoffrey.

“When the fall is all that’s left, it matters,” replies Richard.

The value of the rupee is falling, and the squeamishness around what that will mean for inflation and ordinary consumers has now been dominating the national economic discourse for the last several weeks, if not months. What is less appreciated is the view that many, if not most, economists hold about the matter: if the rupee is falling, the government should not resist its fall.

This view has its critics, who will argue – correctly – that a sharp fall in the value of the rupee will cause inflation, which in turn has a tendency to hurt the poorest sections of the population the most, and that resisting that pain is worth government effort and resources.

The problem with this critique, though, is that it fails to take into adequate consideration the structural flaws not just in Pakistan’s economy, but also in our policymakers thinking, including some flawed ideas that have managed to stay in vogue in the halls of power in Pakistan since Partition: that somehow, the absolute level of the rupee’s exchange rate is a reflection of the government’s success in economic management.

This highly erroneous idea has resulted in now several cycles of the government trying to keep the rupee’s value constant, until finally realizing that expending scarce foreign exchange reserves (which Pakistan rarely ever has enough of to begin with) to maintain the value of the rupee is just not tenable, and then allowing the rupee to crash in sudden fits and starts, rather than a smooth, but manageable, descent.

Why governments choose this inane policy is an open question, though one that we hope some historical context will shed some light on.

A brief history of a terrible idea

On September 18, 1949, the Bank of England made a monumental decision that set off a series of events that has permanently reshaped the Pakistani economy.

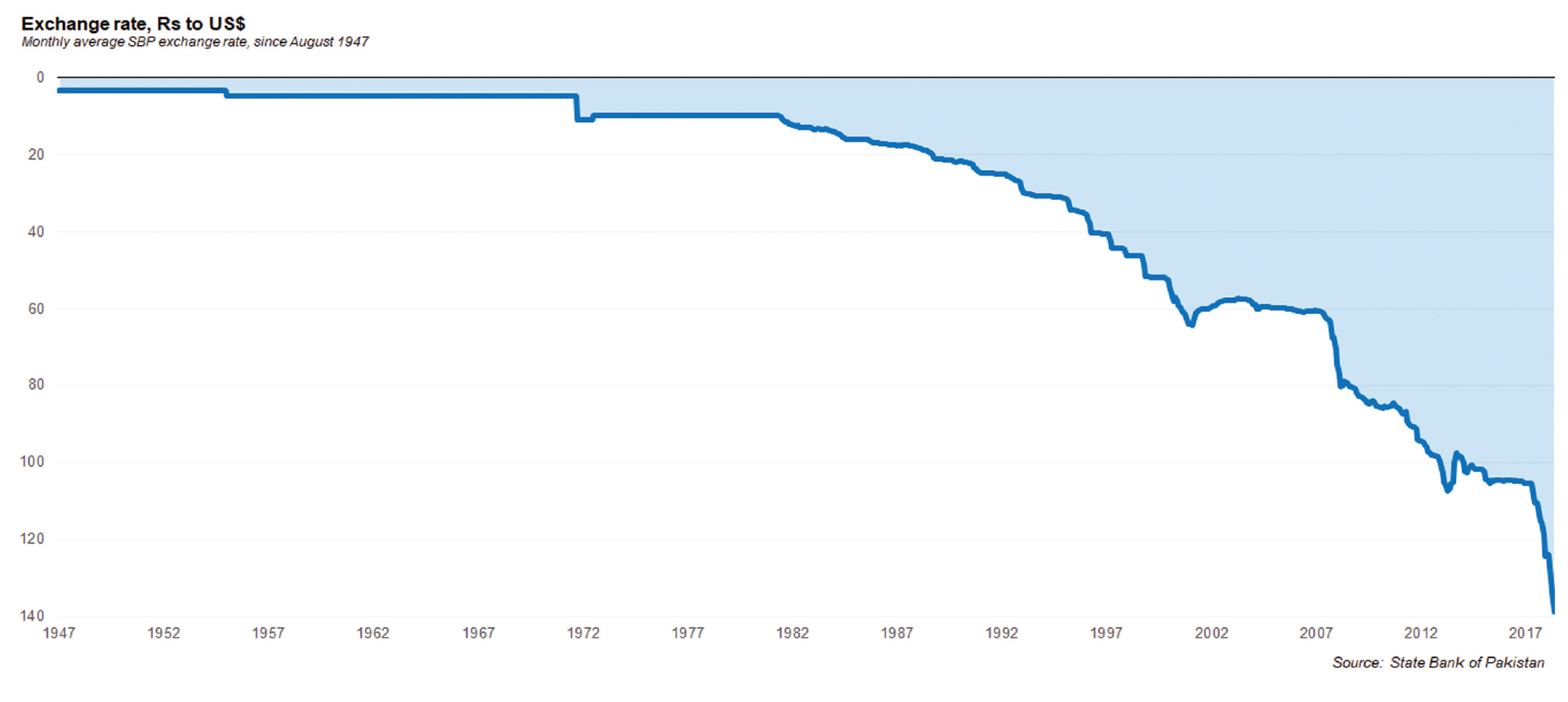

On that day, the British government announced that it would be devaluing the pound sterling by 30%. In those days, while the US dollar had already taken over as the default currency of global commerce, most former British colonies still pegged their currencies to the British pound. As a result, when the British government decided to devalue the pound relative to the US dollar, the government of India decided to follow suit. Crucially, however, (and this, in hindsight, was a blunder of monumental proportions), Pakistan did not follow suit.

The government of Pakistan at the time felt that it did not want to devalue the rupee because it felt that Pakistan’s own macroeconomic indicators did not justify such a move. That decision, however, had a serious negative impact on the Pakistani economy.

At the time of Partition, well over 60% of Pakistan’s foreign trade was with India. This makes intuitive sense: until August 13, 1947, all of that trade had just been intra-country trade. After Partition, those economic linkages did not disappear overnight, and all that intra-country trade became international trade.

However, in 1949, when Indian devalued its currency and Pakistan did not, suddenly Pakistani goods became more expensive to produce relative to their Indian competitors, by a factor of 30% (both currencies had a pegged exchange rate of 1:1 at Partition, which continued for the next two years). This made Pakistani goods and services relatively uncompetitive, and Pakistan’s share of the Indian market started to fade over time.

This is important to remember: Pakistan lost its biggest export market not as the result of the 1965 war – which did result in more legal restrictions on trade between the two countries – but as the result of the much earlier decision not to maintain exchange rate parity with India. Given the fact that the two countries had been managed by the same central bank, and had effectively the same currency until just two years prior, it was not at all unjustifiable for Pakistan to keep the exchange rate parity.

By choosing to prioritise the absolute level of the exchange rate over the consequences for the rest of the economy, specifically the country’s nascent export industries, the government permanently altered Pakistan’s economic trajectory. Instead of integrated regional supply chains (which, by the way, survived the 1948 war just fine, suggesting that Pakistan and India can go to war and continue to trade at the same time), Pakistan is now mostly cut off from its regional markets and has set back the development of its export industries by decades.

Here is where things get interesting: the government of Pakistan did ultimately have to devalue the Pakistani rupee. In August 1955, the rupee declined by 44.2% relative to the US dollar in just one day, more than it would have, had the government decided to retain its parity with the Indian rupee and maintain its exchange rates with its main trading partners.

The government was not able to “save” the value of the rupee and it lost out on economic competitiveness anyway. All the pain, and nothing to gain.

By that point, however, it was too late. The economic linkages that had existed before Partition were now permanently broken, and India and Pakistan went their separate ways with respect to global trade. The Pakistani rupee remained part of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates until that system broke down in August 1971 (largely due to imbalances that the United States had allowed to grow within its own economy, a story that is not directly relevant to that of Pakistan).

However, it took Pakistan more than a decade to fully convert over to the system of a “managed” floating exchange rate, a system which began on January 1, 1982 and has largely remained in place since then. The State Bank of Pakistan lets the rupee trade within a certain range, and intervenes by buying or selling dollars to keep it within the range the government of the day wants it to be.

Trying to control inflation through the exchange rate

Since 1982, almost every single government (with only one exception) has tried to artificially control the price of the rupee as a means of keeping inflation lower than it naturally would be if the exchange rates were left alone.

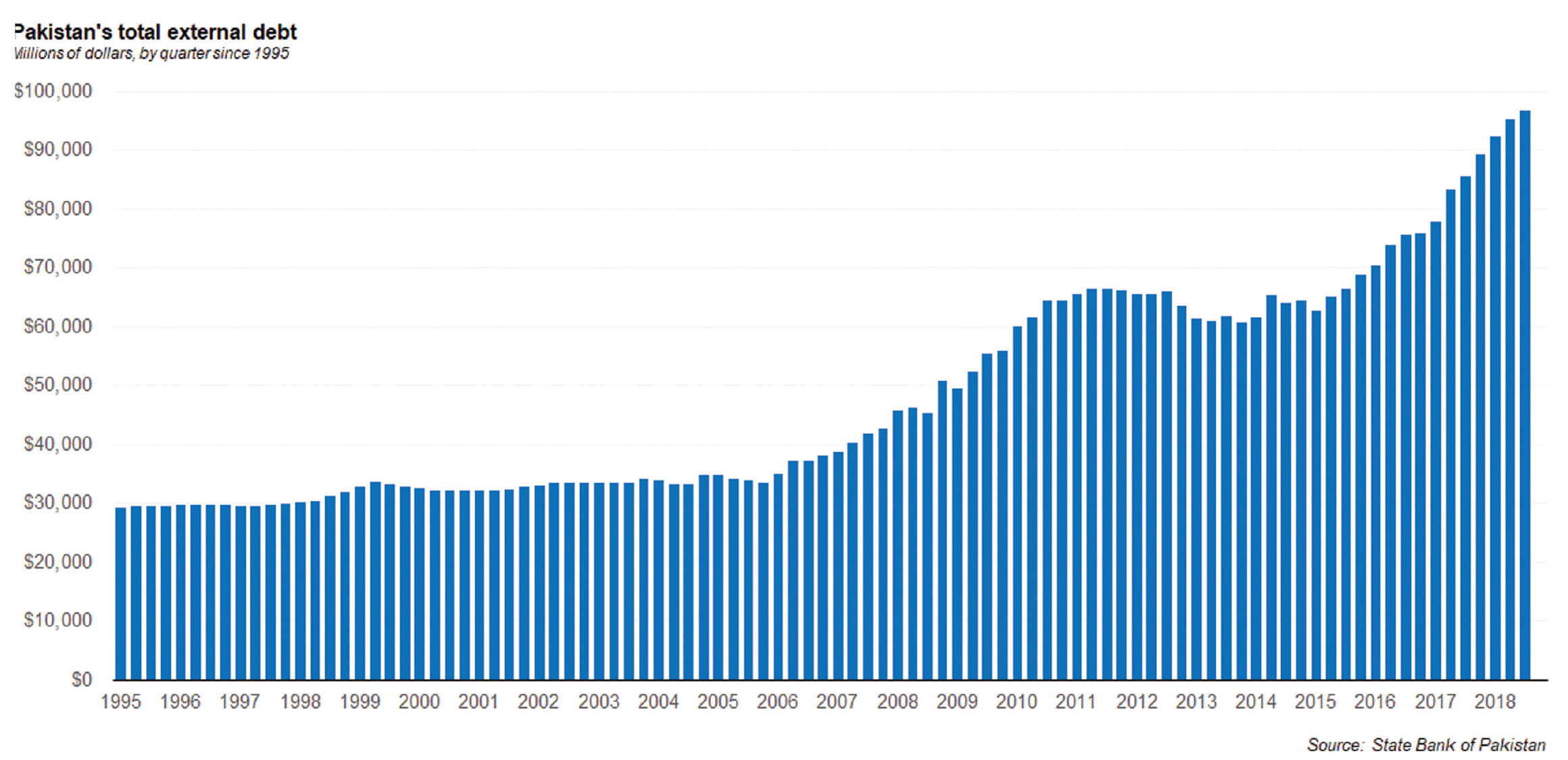

Every time, the cycle is exactly the same: the government raises foreign debt as a means of securing more dollars, which is slowly sells over time so that it can create an artificially high supply of dollars in the economy and artificially high buying of the Pakistani rupee. This is obviously unsustainable, largely because the government is using borrowed money not to finance investment into future income opportunities for the economy but present consumption. Eventually, foreign lenders want their money back and are not willing to refinance, and hence the government’s ability to prop up the rupee ends, causing the currency to suddenly crash.

What makes this worse is that Pakistan ends up with more foreign debt and nothing to show for it. Instead of financing investments into future income – in the form of infrastructure that ultimately increases the productive economic activity of the country – the government is effectively financing the monthly electricity bills and automobile petrol costs for the urban middle class by using borrowed money to artificially deflate the cost of imported energy. A significant portion of Pakistan’s electricity generation relies on imported fuels.

The critical thing to remember is that this debt and inflation cycle is not something that is imposed on the government of Pakistan by an external lender. It is a policy choice made by the government itself, one that many international lenders – including the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – would like Pakistan to get out of.

But a look at the history of the country’s inflation and exchange rates reveals that this exercise only has the effect of creating unnecessary shocks. It does absolutely nothing to arrest inflation, or the exchange rate. A substantial proportion of the variation in exchange rates and inflation – including the size of the subsequent economic shocks – can be explained by just how much effort previous governments have put into trying to control both.

A brief history of Pakistan, as told through inflation

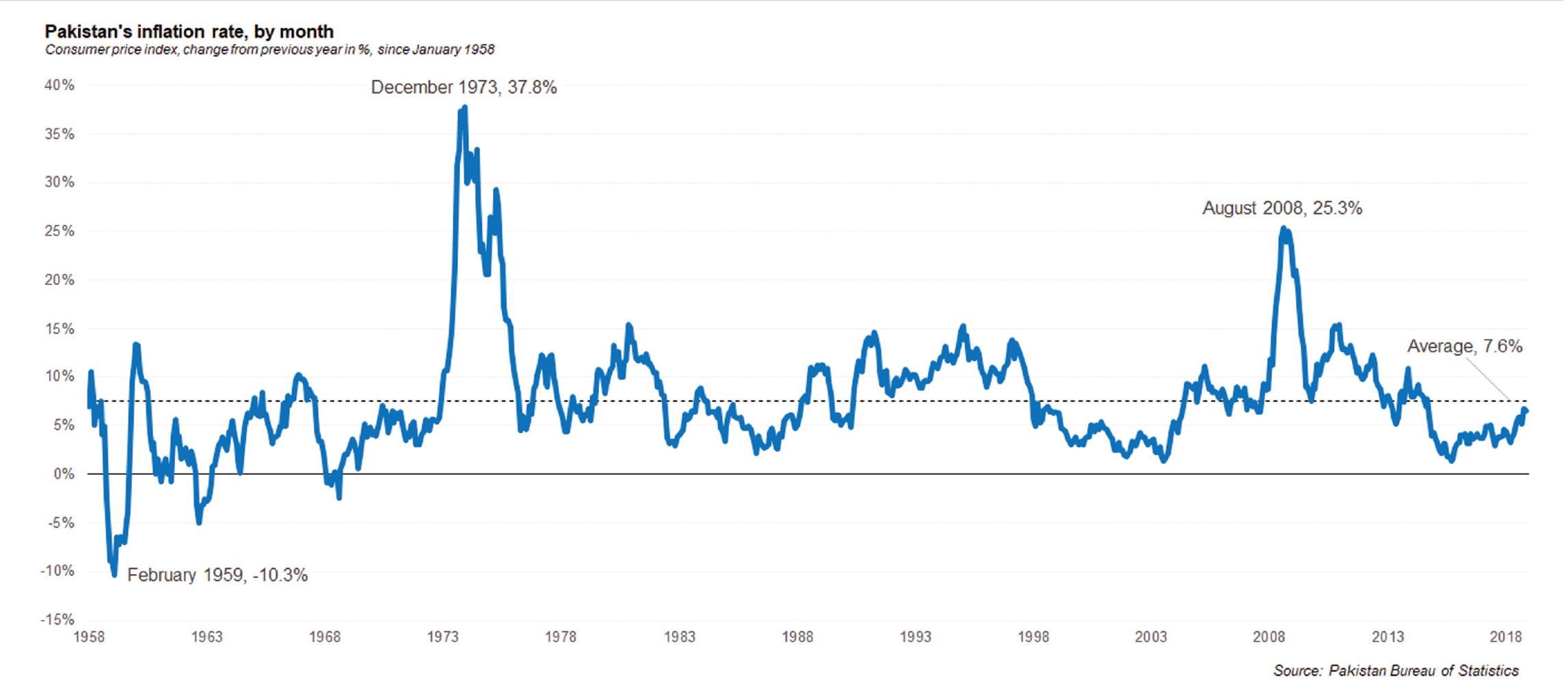

Since August 1947, the Pakistani rupee has depreciated at an average rate of 5.38% per year, according to data from the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP). The Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) does not make inflation data available for that same period of time, but since January 1958, the country’s inflation rate has averaged at around 7.55% per year.

Those averages hide significant variations. However, we are able to surmise at least one significant inference from the historical data: the longer the government uses artificial means to keep inflation below 5%, the worse the subsequent increase in inflation. Reversion to the mean, in the case of the Pakistani economy, is a mean, chaotic, highly disruptive process.

The first government for which there is complete data on inflation is the Ayub Khan Administration, during whose time inflation averaged 2.8% per year. However, once again, the average hides considerable variations. The late 1950s and the early 1960s were a period of sharp volatility in prices and inflation rates, with deflation setting in through most of 1959, resulting in the lowest ever recorded inflation number in Pakistani history of -10.3% in February 1959. However, by February 1960, inflation was up to 13.3% before dropping back down to deflationary numbers for most of 1962 and 1963.

Inflation jumped sharply after the 1965 war, reaching 10.2% in December 1966 before declining for the remainder of the Ayub era. Contrary to popular perception, inflation was actually quite low for most of the time that agitation against the Ayub administration took place from 1967 through 1969. In March 1969, the month that President Ayub was forced out of office, inflation was a timid 3.6%. Some of the anti-Ayub slogans shouted by the protestors in those years may have been about the rising prices of potatoes, but the economic reality suggests that overall prices were hardly skyrocketing.

The Yahya Khan administration was marked by civil war, followed by international war, but inflation remained relatively muted during that time. It is possible that war-time price controls and rationing helped make the numbers look better than they might have been, but inflation during the Yahya era averaged just 4.7% per year.

It is highly likely that the next government – the Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Administration – had to bear the brunt of all of those distortions in prices created by war and the Yahya government, because inflation suddenly skyrocketed shortly after Bhutto came into office.

From January 1972, the first full month that Bhutto was in office, until December 1973, almost two full years later, the rate of inflation rose almost every month. It peaked in December 1973 at an annualised rate of 37.8%, the highest ever recorded in Pakistani history.

The Bhutto Administration was never fully able to get a grip on inflation, and no doubt was not helped by the 1973 oil crisis, which raised international oil prices sharply, causing inflation to skyrocket worldwide. By the time Prime Minister Bhutto was deposed in a military coup on July 5, 1977, the Bhutto Administration had averaged 16.0% inflation per year during its time in office, the highest of any government in Pakistan’s history.

The Zia Administration did better, and was able to contain average inflation to 7.2% per year during their tenure, though they were helped by more stable global commodity prices, and a steady influx of American money, which kept the exchange rate with the US dollar relatively more stable. Nonetheless, the Zia government did repeatedly try to control the exchange rate as a means of controlling inflation, and repeatedly failed at the effort until the president’s death / assassination in August 1988.

Both of the tenures of both Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s were marred by the exact same cycle. However, as commodity prices fluctuated somewhat more frequently in the 1990s, inflation was also more volatile than in the Zia era.

The most egregious attempt to control both the exchange rate and inflation was in the Musharraf Administration, which sought to maintain an exchange rate of approximately Rs60 to the US dollar for nearly the entirety of its term in office. Inflation during that time averaged a relatively tame 6.6% per year, though the rate had started coming down under the latter part of the second Nawaz Administration and started creeping up in the last year of the Musharraf Administration.

The full extent of the pain caused by the Musharraf government, however, was not felt until the Pakistan Peoples Party, led by then-President Asif Ali Zardari came into office in 2008. In the very last month that President Musharraf was in office – August 2008 – inflation hit 25.3% on an annualised basis. The rupee lost a third of its value in one year.

The only government that made almost no attempt to control the rupee’s exchange rate was the Zardari administration, which let the rupee be a truly market-based free float. Unfortunately, its tenure also coincided with a sharp rise in global oil prices right when Pakistan’s need for imported energy hit its peak. As a result, despite making no attempts to control the exchange rate, inflation remained higher than the historical average, and clocked in at an average of 13.2% per year. Even if one excludes the first year (which was really the spillover effects of the Musharraf administration’s decisions), the Zardari administration averaged a 10.9% annualised inflation rate during its tenure.

The third Nawaz Administration famously tried to peg the rupee at Rs100 to the US dollar, and mostly succeeded in doing so, though at the cost of rapidly increasing the foreign debt burden of the country. While inflation averaged just 4.9% during their tenure between June 2013 and July 2018, it is too early to tell just how much the damage will be in terms of currency depreciation and inflation, as a result of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and Finance Minister Ishaq Dar’s decisions.

The choice facing the Imran Khan administration

So what are the government’s options under the current administration? Is defending the value of the rupee even an option? And if it is, is it even desirable? And if the rupee should be allowed to fall, how much farther will it fall, and what will be the impact? Why is it considered a desirable outcome to let the rupee find its own level without any government intervention?

Here is the simplest answer to all of those questions: the government is already so far in debt, and has so much of its debt maturing in the coming months, that it simply does not have the option of trying to prop up the value of the rupee as a policy option. It absolutely has to let the rupee find its own level.

So the only question remains: why is this a desirable outcome? Because maybe, just maybe, the Imran Khan Administration can inculcate into the government of Pakistan a tradition of leaving the rupee exchange rate alone, which in turn will mean that while the rupee’s value will continue to depreciate every year, there will much fewer – if any – sudden and sharp declines in the value of the currency that we witnessed this year, and in 2008, and in several years prior.

Here is the logic behind why that makes sense: if businesses and individuals know that the rupee will decline by between 5% and 7% in value every year, then they can plan for that. If inflation consistently averages between 7% and 9% a year, that makes prices and interest rates much more predictable, and thus easier to plan around.

High inflation is not good, and certainly having a tamer level of inflation would be a good thing for the economy. Sub-5% inflation consistently would certainly be highly desirable. But achieving that level of inflation would require two things: the fiscal deficit remaining consistently and significantly below the real (inflation-adjusted) economic growth rate, and for Pakistan’s exports to be significantly higher as a percentage of GDP than they are now.

Both of those preconditions require a decade or more of sustained policies to achieve, and in the absence of those, the least the government can do is avoid the situation we are about to have, where the inflation rate is less than 5% in 2018, and likely to close out 2019 well north of 10%. Two years of 7% and 8% inflation are better than that kind of volatility.

Hence, the Imran Khan Administration would be better off letting the rupee collapse to whatever level it needs to, and then let it trade completely freely. Nobody will blame the government for what happens in its first year. And in any case, the government would be wise to let whatever pain needs to happen occur in its first year in office so that it can spend the remaining four years building up a better track record to eventually campaign on in 2023.

The coming structural change

What would the economy look like if the government left the rupee alone?

An indication of what that might look like is visible in the numbers from the post-Zia era, when inflation has averaged 8.28% per year, and rupee depreciation has averaged 6.92% per year. If those numbers continue with relatively little variation from year to year, the economy would be better off than it is now, when it incurs a massive shock to the system about once every five years.

More importantly, however, the government would be wise to recognise that structural changes in the global energy markets mean that it is entirely likely that oil prices will remain relatively low for the foreseeable future, and may never rise again. This is because global demand for petroleum products is in secular decline as more and more cars become all-electric and renewable energy takes a greater share of global electricity production.

As a result, allowing depreciation of the rupee will not have nearly the same inflationary impact now that it did in previous years.

How do we know this is true? Because the rupee just dropped in value by a greater percentage (33%) in 2018 than it did in 2008 (29%) and inflation is going to be much tamer: 25% in August 2008 versus a much tamer 13% peak inflation expected some time next year. That difference is entirely due to oil prices staying low in the global markets.

Simply put, there is no point in wasting any government energy or resources in managing the exchange rate. Let the rupee float. It will sink first, but it will eventually find an equilibrium that works for the economy.

Great read as usual… kudos to Profit for writing about something that matters as opposed to fluff pieces.

Its may be beneficial in several ways but it may create greater issues for pakistani lower class people.

Great piece of knowledge. I know that Pakistani public is in habit to see the temporary “everything fine” environment which makes it difficult for Govt to decide as they need votes after 5 years. Maybe its time the brains from public stand up and give Govt the relaxation to fix the economy with no pressure at least from public. Thanks for this article. Love PT

Such a one sided argument. Well what are the harms of letting the rupee sink?

This good piece of writing have only one flaw.. It’s eyes on idealistic approach only.. which may be more harmful in our case 🙂

Really one sided and weak arguments presented in the article. Lets discuss the several issues that will arise if rupee parity is allowed to fall freely:

1. Due to low confidence on the economy due to precarious FX reserves situation, hoarders will start buying massive amounts of FX, that will result in huge rise in speculative demand for $ and a serious dollar supply shortfall that will result in stagflation which would exacerbate the fall in Rupee parity and make Rupee worthless against the Dollar and other currencies.

2. With every fall in Rupee parity, our foreign debt repayment liability will jump further in Rupee terms by billions of Rupees and printing of more Rupees will cause further inflation.

3. Public sentiments on the performance of PTI government will worsen and they won’t really understand that it is due to huge foreign debts accumulated mainly over the last decade and the huge repayment requirements. They will treat Rupee fall as a direct result of PTI government’s policies (maybe due to their inexperience?). This in turn will force the public to quickly convert all their investments and savings in dollars, which will further weaken the Rupee.

4. While Rupee will keep on falling against dollar to new lows every week (so from 140 to $1 to 200 to $1 and soon Rs 400 to $1), worker salaries and profits will not be increased accordingly by public and private sector companies and hence the salaried class will be earning far less money in $ terms than what they were earning before. While their expenses which are mostly linked to imports, will sharply increase. The result will be catastrophic as the overall population will move towards poverty.

5. This will also result into public unrest and hence deteriorating law and order situation as people will call for ‘good old times’ of PML(N), PPP and army rule when Rupee was at least stable.

So unless you really hope complete failure of the nascent PTI government, asking for Rupee to let it fall to crash levels is really anti Pakistan and anti people.

This is one of the dumbest things I’ve ever read

Letting your currency crash is one of the dumbest things. Can you name 1 country which did that and it worked well for them? Yeah right look at history of Iraq, Zimbabwe and other economies which experienced stagflation and decades of unemployment after their currency crash.

But, yeah who cares about facts!

LOL. 😀

There’s a reason every Central Bank around the world has the task of managing currency values and control money supply accordingly. Any economic student would know that and the perils of a Laissex Faire economy.

Excellent points. Decline in the value of rupees will mostly hurt the poor and middle class. Statics shows that Pakistan’s poor are much better off (in terms of PPP dollars per day) than those of Bangladesh and India:

Poverty headcount ratio at $1.90 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population)

Pakistan 6.1% in 2013 dropped to 4% in 2015

Bangladesh 19.6% in 2010 dropped to 14.8% in 2016

India 31.1% in 2009 dropped to 21.2% 2011

With decline in exchange rate poverty headcount of Pakistan will increase, perhaps that is the intention, so our export will become more competitive. But explain that to a poor worker who will suffer the most.

I’m not sure how anyone who understands basic economics can disagree with this article. Very well written.

Ok let the rupee fall. Let’s devalue rupees “The” National Citizen loses huge amount of their earnings because everything that is usable is imported (from raw material to machine). On government side also the easy way out is to increase the Taxes on citizens, once again “The Poor Pakistani National Citizen have to bear huge loses on their income because in effect the cost to run government will also increase, payments for local projects, the return of foreign loans, etc etc. The higher the currency difference the bigger rivers of rupees will flow from our hands.

A good informative article but with no understanding of consequences on the subject.

Whatever the government is doing in background they need to optimize their efforts on the other hand keep the currency strong, in this condition particularly, it will be easier for government and citizens too

Pretty through. Good read.

Leting the rupee to flot freely would worsen Pakistan’s economy and currency crash. Pakistan is developing economy and investors confidence will plunged pushing millions into poverty. What we need to do is review our FTA (free trade agreements), introduce protectionist policies to encourge local manufacturing. Our import bill is skyrockting, we need to look into that first before letting rupee flot. If Donald Trupm can increase duties on chinese products why can’t we review our trade defecit with China and other countries.

Comments are closed.