Perhaps it was fitting, perhaps it was ironic. The most expensive team in the fourth edition of the Pakistan Super League (PSL) – the Multan Sultans – became the first team to be elbowed out of the title race. Ali Khan Tareen, son of billionaire businessman and politician Jahangir Khan Tareen, paid $6.35 million for the franchise fee for the Multan Sultans, more than twice that paid for what was previously the most expensive team in the league, the Karachi Kings franchise, leading many to ask the question: is the PSL a commercial venture or a vanity exercise for the country’s wealthy elite?

The Multan Sultan’s lack of success in the tournament was deemed by some cricket pundits to be an anomaly in an otherwise hotly contested tournament. Not that anyone could blame the new owners, who only bought the team in December 2018, giving them only a few months to prepare for the tournament.

People close to the PSL leadership, and who know about Ali Tareen’s aspirations, feel that the decision to buy the franchise at such a high price was not a bad one for him, if not a purely financial one on his part.

Ali Tareen has been positioning himself to become the face of South Punjab, no mean feat given the fact that it is a politically coveted part of the country that already has several well-known figures prominent in national politics. And Ali’s first foray into that contested political arena did not fare quite as well as he might have liked: in 2018, he unsuccessfully ran as the candidate for the ruling Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) in the by-election of NA-154, Lodhran.

He has already been working on different projects, in sports as well as education, in the region. The ownership of the PSL franchise has now brought the young Tareen into the limelight. It is likely that he and his father hope that the ownership of the franchise will give him political mileage in the years to come.

“It’s not bad to have political mileage by doing something good for society. He had been working on different projects even before Multan Sultans was up for sale. So, it’s not that he started to work after acquiring Multan Sultans,” said one former PSL official, speaking on condition of anonymity.

But while Ali Tareen may have bought the team for non-economic reasons, what about the other owners? And what about the league itself? Just how commercially viable is this business?

How is the league doing financially?

The Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) ran two press releases during the ongoing PSL 4 quoting former legends Wasim Akram and Shahid Afridi urging fans to turn out in big numbers at stadia across the country to make ‘Pakistan’s own event’ successful. That release, combined with other news coming out of the PSL and PCB more broadly, suggests that the league is not doing well financially, forcing the PCB and the league management to beg fans to come out in droves for matches.

Franchise owners acknowledge that they are currently losing money, but declined to provide details of their financial health when asked by Profit.

The PSL’s financial struggles stand in contrast to a booming global sports industry. Sports tourism and entertainment, according to the media and entertainment research firm Technavio, is already a $1.41 trillion industry worldwide. It is projected to achieve a projected $5.72 trillion level by 2021. Technavio’s market research analysts predict that this market will grow at a compound annualised growth rate (CAGR) of more than 41% by 2021.

At a PCB meeting earlier in February, a week prior to the beginning of the ongoing fourth edition of the PSL, it was disclosed that all participating PSL franchises were defaulting on their financial obligations to the PCB one way or another.

Profit has interviewed many top officials of the PSL and owners of some franchises in its previous coverage of the Pakistan Super League, in 2017 and 2018. Back then, the owners wanted to make it known that they were in the league for the betterment of cricket in the country.

A veteran sports journalist Anisuddin Khan rebuffs this notion. “What have they done for cricket before PSL? They are in the league to make money, and they are businessmen. If they make money, it is their right. But if they have been losing money, well then profit and loss are both part and parcel for any business. PCB is not obliged to pay anything for their losses, but they did after the first edition,” he said.

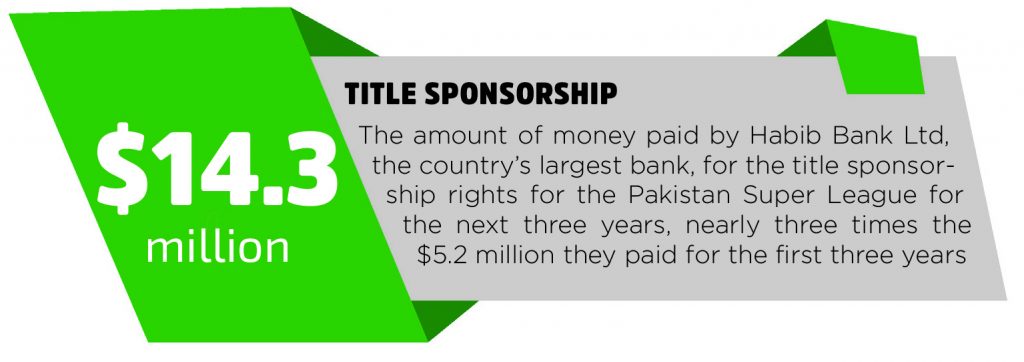

Despite the appeals for people to show up in stadia for matches, ticket sales are a relatively smaller portion of total revenue for PSL teams. The bulk of franchise revenues comes from sponsorships for the televised matches. The PCB signed a $14.3 million title sponsorship deal with Habib Bank Ltd (HBL), the country’s largest bank by assets, for the next three PSL editions, distributing half of it among six franchises.

According to ESPNcricinfo, PSL franchises incurred losses ranging from Rs200 million to Rs700 million each in the first two seasons of the league. The franchises have been seeking financial restructuring of the league as well as tax exemptions from the government to become profitable.

Since the franchises are deemed services businesses by the government, they are subject to provincial sales taxes. As part of its bid to help franchisees continue to make money, the PCB had sent a letter to the finance minister of Punjab, the province that is home to three of the six teams.

The letter included consolidated financial details of the five franchises from the 2016 and 2017 seasons. According to the letter, the Lahore Qalandars – the least successful franchise on the field so far, having finished last each season – have incurred the largest losses: Rs312 million in 2016 and Rs421 million in 2017. The Qalandars are owned by Fawad Rana, owner of the Qatar Lubricants Company, a distributor of lubricants based in Doha.

Nadeem Omar’s Quetta Gladiators, the lowest-cost franchise in terms of its bid price, on the other hand, has accrued the smallest losses: Rs46.5 million and Rs63.5 million in 2016 and 2017 respectively. The Gladiators are one of the most successful franchises, led by Pakistan skipper Sarfaraz Ahmed and have finished runners-up twice in three editions.

Is a turnaround in the offing?

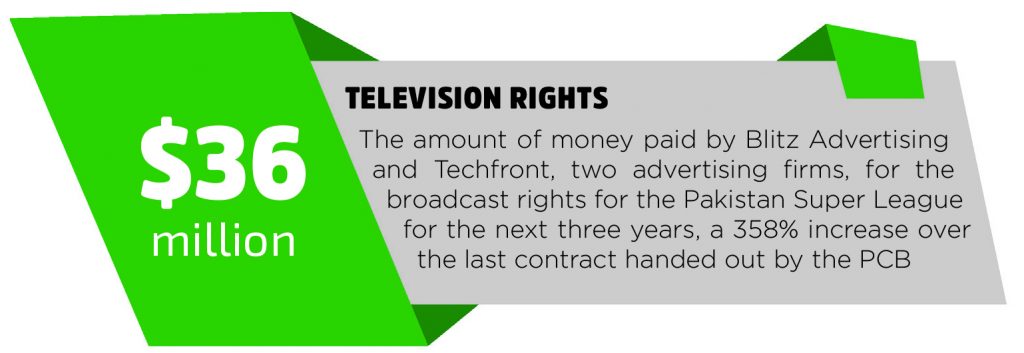

Part of the reason for the initial losses incurred by the league’s teams might simply be due to the fact that sponsors and advertisers had no idea what to expect when they first bid for television rights and advertising rates for the league, and may have bid too low. And the PCB, not having any benchmarks of its own, ended up accepting those benchmarks.

For instance, the $14.3 million title sponsorship deal that the PCB struck with HBL is nearly three times the price of the $5.2 million title sponsorship contract awarded in 2016. The broadcast rights sold for even higher. Blitz Advertising and Techfront paid $36 million in December 2018 for the rights for the next three seasons, up 358% from the last time the rights were sold. Those higher revenues are likely to affect the bottom lines of the franchises positively in the coming few seasons.

According to one source familiar with the matter, part of the reason for the willingness of sponsors to pay so much more is that they now see the media value of what they are paying for, given the high level of interest in the league from television viewers across Pakistan, particularly in the coveted upper middle class demographic.

The ratio of sponsorship deal value to media value received by the sponsor is measured at between 1:8 and 1:10, according to our source, who cited a study conducted by Nielsen Sports. Those are numbers that are significantly higher than is normal in other sporting leagues, where ratios of 1:3 are more typical. The PCB’s ability to negotiate higher values on its sponsorship deals is likely to erode that ratio, while still keeping it profitable for the companies making that investment.

In 2018, the third edition of the PSL was estimated to have had a combined media valuation of Rs3 billion (then $24 million) for all six teams, according to Najam Sethi, then-CEO of the PCB., who was citing a Nielsen Sports evaluation.

The higher revenues from advertising and title sponsorship rights means that some franchises are already starting to see healthier bottom lines. According to a source familiar with the matter, Peshawar Zalmi, Quetta Gladiators, and Islamabad United are likely to hit profitability this year, whereas the Karachi Kings and Lahore Qalandars are likely to hit breakeven. This estimate is before taking into consideration any external sponsorship deals the franchises may have struck on their own.

Each of the teams has managed to find a corporate sponsor beyond just the title sponsor for the entire tournament.

The high cost problem

Part of the cost problem for the franchises has been the fact that they have to pay the franchise fees to the PCB in US dollars. Last year, the Pakistani rupee devalued significantly against the US dollar, losing 32% of its value from December 2017 to November 2018. It has roughly remained stable since then.

The other big concern is the taxes paid on the franchise fee. According to the figures in the PCB’s letter to the Punjab finance ministry, franchise fees made up anywhere from 30% to 91% of a franchise’s total costs in 2016 and 2017.

According to the franchises, the franchise fee, taxes, players’ match fees, logistics in UAE, dubbed as a home away from home for Pakistan while it continues its exile from international cricket following the 2009 Taliban attack on the Sri Lankan cricket team, adds up to make them to incur heavy losses.

Despite all these reports, the newbie in the PSL – Ali Tareen, leading a consortium – has paid a franchise fee of $6.35 million when the PCB’s base price was set at $5.21 million.

The young Tareen is the son of one of the richest men in Pakistan, Jahangir Tareen, who owns a controlling stake in JDW Sugar, the largest sugar manufacturer in the country, and a company listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange.

Tareen bought the franchise despite the fact that it made a loss of approximately Rs400 million in the one season they played in 2018. PCB terminated the contract with Schon Group, the previous owner of the franchise, after the latter ‘failed to meet financial obligations’. Given the high franchise fee, the Multan Sultans of Ali Tareen will take more time to hit profitability.

The league coming into its own

“The main reason for us to launch the PSL was simply patriotism. The IPL (Indian Premier League) wasn’t allowing our players to play in their league so there was a dire need for our own league. But we made sure that it was not just a ‘me-too’ replica of IPL and it should have a quintessence of Pakistan in its nature,” said one PCB source.

“We now have our own PSL ‘characters’ like Fawad Rana (owner of the Lahore Qalandars) and Viv Richards (legendary West Indian batsman and Quetta Gladiators mentor) where fans have developing association with.”

However, there is some concern about the departure of Najam Sethi from the helm of the PCB. The PSL was Sethi’s brainchild, but resigned from the PCB after the PTI-led Imran Khan Administration came into office in 2018.

“I have a lot of differences with Sethi but the ongoing PSL edition is not at par with the bar Sethi has set in the previous three editions,” Shoaib Ahmed, a former PCB employee told Profit. He said that Sethi was able to create hype for the league in media. Ahmed now runs a cricket magazine called Scoreline Asia.

Our anonymous PCB source has also been full of praise for Sethi and said that it was only he who was able to push the rigid PCB bureaucracy to the wall to kick off the league. The source was critical of current PCB CEO Subhan Ahmed. “The man simply doesn’t have the capacity and vision to take the PSL ahead,” he said.

Shoaib Ahmed concurred with our source’s opinion.

“He is good at knowing the ICC [International Cricket Council] rules and regulations and he has his strengths but he doesn’t has the capacity to lead PSL. However, I believe franchise owners wouldn’t let anyone deplete the brand value the league has already garnered. So I feel and hope PSL’s brand will not go down,” said the source.

Is PSL financially viable?

Salman Sarwar Butt, who was one of the main officials of the Pakistan Super League (PSL) during its pre-launch phase, believes cricket leagues have great economic potential apart from sporting spectacle.

The second most followed sport after football, cricket’s most successful league – India Premier League’s each match now worth $9 million – four times more than highly followed NBA basketball games in the United States. The overall value of the IPL ecosystem has increased from $5.3 billion last year to $6.3 billion this year. The renewed broadcast rights deal was the major contributor to this increase.

Among franchises, the Mumbai Indians are estimated to have a brand value of $113 million, continuing to top the charts for the third season in a row. Right behind them are the Kolkata Knight Riders (KKR), with a brand value of $104 million.

Meanwhile, the combined media exposure brand value worth for Pakistan Super League season three has been calculated at $230 million, according to a press release issued by the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB). According to Nielsen Sports, who conducted extensive research on the league, the PSL and its official sponsors generated 38% higher value than the previous season, showing a rapid growth in the league in PSL’s third edition.

“Cricket leagues need to be built over a period of time. Any investor coming into a compelling product in the Gulf and UAE could see returns starting from 10% to 12% and building up further into very good returns over a period of time. The potential for products like these, especially in the open economies like the UAE, is huge,” he said.

Butt further said that there’s great potential for sports league industry in Pakistan as there are about 70 million people who have a ‘propensity to spend’ on such leagues. He was referring to country’s middle-class population, which exceeds total population of many European countries, where sports industry has highly been matured and lucrative.

He said that the sports league in Pakistan demands very low investment in comparison with western countries as here an investor can buy a whole franchise in less than the amount a player is traded for example in a football league. “It’s an industry rising in the region. I see great potential both in the Gulf as well in Pakistan,” Butt said.

However, Butt was interviewed ahead of the launch of the UAE T20x, which was scheduled to begin in December last year. Butt was the CEO of the league, which unfortunately, was called off at the eleventh hour.