Aqeel Karim Dedhi is one of the richest men in Pakistan. He is also very fond of sacrificial animals. Raising slaughter animals is a tradition he takes considerable pride in. He spends what would be a fortune for many on buying cows and bulls every year. And he is particularly fond of cattle from Sibi.

Sibi is among the poorest districts in all of Pakistan. Nearly half of its population – 48.2% according to the most recent National Socio-Economic Registry (NSER) Poverty Profile report – live below the poverty line. Aqeel Karim Dedhi, a stockbroker and real estate investor famous in the country’s business community by his initials AKD, has a net-worth estimated well north of $1 billion. And when Eid-ul-Azha rolls around, there is no place else he would rather get his cattle.

Sibi’s cattle is the most expensive and Dhedhi has a liking for them. Sibi’s bulls are the toughest in the world because they are all purebred, Dedhi was quoted as saying in the Herald. He went on to say extol the virtues of Sibi’s cattle and the people who raise them, saying that “the people of Sibi do not sell their cows, they do not allow inter-breeding.”

The statement, of course, is a misconception: animals grow bigger and stronger through husbandry that frequently requires cross-breeding of different breeds of cattle.

Nonetheless, whatever the reason for Dedhi’s preferences, there is no denying that the annual maweshi mela (animal show) that takes place around Eid-ul-Azha at his home is testament to this fondness for livestock.

Profit has learnt that at least 100 groups arrive at Karachi’s biggest maveshi mandi (cattle market) in Sohrab Goth from Sibi. Each group has between five to 10 people. There is usually a salesman, a sweeper, a person who prepares the fodder, and another who feeds the cattle, and any number of these functions can be performed by more than one person. The number of people in each group varies based on the number of animals a group brings. The traders or the owners of the expensive livestock are not usually poor but the staff that come along with them are.

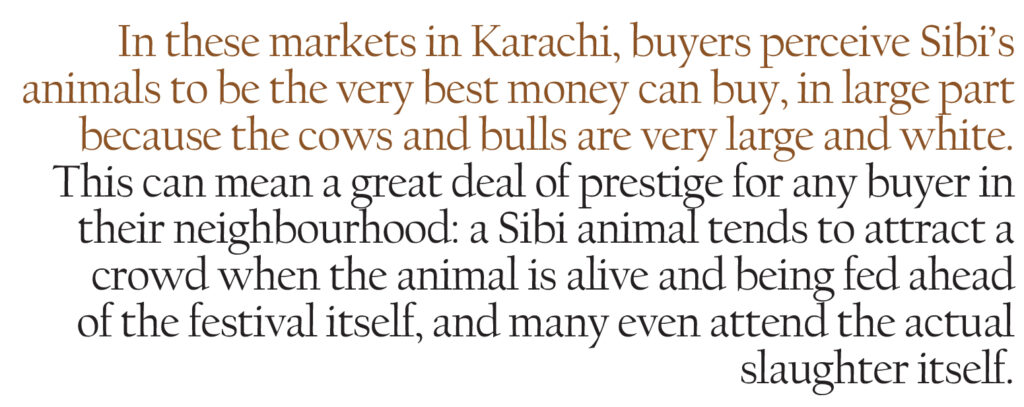

In these markets in Karachi, buyers perceive Sibi’s animals to be the very best money can buy, in large part because the cows and bulls are very large and white. This can mean a great deal of prestige for any buyer in their neighbourhood: a Sibi animal tends to attract a crowd when the animal is alive and being fed ahead of the festival itself, and many even attend the actual slaughter itself.

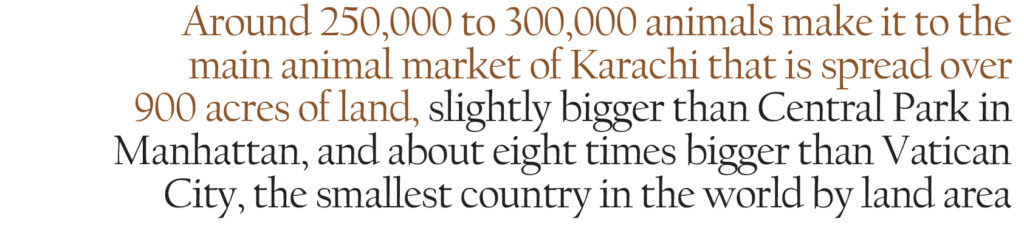

Around 250,000 to 300,000 animals make it to the main animal market of Karachi that is spread over 900 acres of land, slightly bigger than Central Park in Manhattan, and about eight times bigger than Vatican City, the smallest country in the world by land area.

And it is not just the rich who splurge on buying expensive animals during Eid-ul-Azha. Many of middle class buyers save money for the whole year to buy a sacrificial animal of their choice, often forgoing other purchases in order to be able to buy an expensive animal during that time of the year. Social prestige, combined with perceived religiosity are a powerful motivator for many people, though others perceive it as the best way to fulfil what they consider a religious obligation.

Irfan Mujahid’s brother Asim Mujahid saves money throughout the year to spend on Bakr Eid. “My younger brother astonishes us every year when we go to buy a sacrificial animal. When we are about to buy an animal for around Rs60,000 to Rs70,000 according to our budget, Asim ask us to increase the budget amount by Rs50,000 approximately and buy an expensive animal. He has been saving money throughout the year to eventually spend on buying a sacrificial animal,” Irfan said.

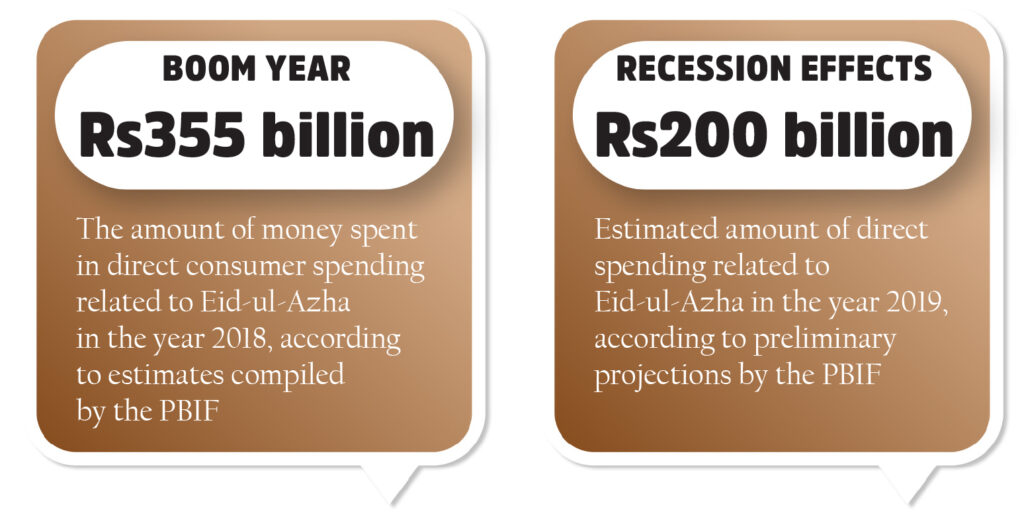

While the government does not keep track of precisely how much is spent on Eid-ul-Azha sacrificial animals each year, it is estimated that nationwide, buyers spent upwards of Rs355 billion in direct spending on Eid-ul-Azha last year, according to Mian Zahid Hussain, president of the Pakistan Businessmen and Intellectuals Forum (PBIF), a think tank and business advocacy group.

The PBIF estimates that approximately 8 million sacrificial animals were purchased last year at a total price tag of Rs298 billion; another Rs26 billion went to butchers for the actual slaughter of the animals, and an estimated Rs10 billion was earned by the traders of hides. The PBIF’s estimates do not include the spending on other supplies such as animal fodder, rope, and other accessories for decorating animals, all of which see sharp increases in prices around the Eid season.

This year, however, is likely to be slower than last year, with PBIF forecasting up to a 40% drop in Eid-related economic activity in 2019 compared to the previous year. The main reason: the wide economic slowdown is likely to impact people’s spending on what is still largely viewed by many buyers as a discretionary item of spending.

“The condition of the economy is very bleak this year. I believe the economic activity this year would be around Rs200 billion on Eid. Activity in the livestock markets have yet to be observed despite the fact that Eid is just around the corner. It was not the case last year,” he said.

Profit sources corroborate that buying activity in the animal market is negligible so far this year, which was not the case last year.

“Costs have increased and therefore livestock traders must be expecting to charge more as compared to last year. But the income of an average person has decreased during the last one year. The price of the livestock has gone up and the buying power has gone down. So, it’s a double-edged sword for the overall business on this Eid. This is the reason I am expecting a big slash in the overall trade,” Zahid explained.

He added that the leather industry has been struggling due to an increase in the cost of doing business and is thus not able to take advantage of the massive rupee devaluation, which should otherwise have boosted the export-oriented industry.

“There will be fewer animals sacrificed this year. Many people who used to offer sacrifice of a goat would opt for a share in a cow. Many of those who opted for a share in cows may not be able to take part in the rituals at all this year. And despite the fact that there will be lesser hides this year, tanners would be reducing price for hides since they are already struggling,” he said.

A person who is qualified and willing to perform sacrifice ritual can fulfill their obligation by sacrificing a goat or lamb or take one share in a cow, which has seven shares. Offering a share in a cow is a cheaper option as compared to offering a sacrifice of a goat.

Karachi’s Mohammad Ali went to Mirpurkhas this year to buy goats but says it has been too expensive and he did not buy one. Traders were asking for Rs 30,000 to Rs 35,000 for an average healthy goat. He is now waiting for the monsoon rains, which brings traders into the bargaining zone.

However, Ali says goats were also expensive last year as well as there was high demand and low supply. The livestock traders want to charge the same rate this year as well. But the buying power of the average buyer may not let them charge last year’s price. Either they have to lower their expectations and charge less or take their livestock back with them.

Dhedhi knows that many people consider his animal show ostentatious, an uncouth display of wealth, but he believes that sacrificial slaughter has to be done with ceremony. “My father and grandfather taught me this, and my children will do this after me,” he says. Much of what Dhedhi says and does is part of his family tradition and it seems it won’t be stopping with him.

Livestock and the Pakistani economy

But what makes the display particularly egregious is the fact that livestock – while it may become big business during Eid – generally a poor person’s trade in Pakistan. One in every six Pakistani households is affiliated with the livestock sector and it constitutes 11% of the country’s GDP. That 17% affiliated with the livestock trade, however, tends to be among the poorest households in the country.

This, incidentally, is despite the fact that Pakistan has among the highest populations of virtually every kind of livestock: among the top 10 populations of cattle, buffalo, sheep, and goats in the world. Yet that animal population is dispersed over a large human population that seeks to use them for subsistence-level livestock farming.

Over the past few years, several companies and provincial government have sought to remedy that situation by encouraging more Pakistani farmers to breed their animals for export, but that strategy has thus far yielded middling results at best. After increasing at an average annual rate of 27.8% per year for the 12 years between 2003 and 2015 reaching a peak of $264 million, Pakistan’s meat exports have declined over the past three years by 13.8% to $227 million.

“If we can’t compete in agriculture, then we should really just give up trying to do anything,” says Kazim Namazi, CEO of Global Gums & Chemicals, an agribusiness based in Karachi.

The only publicly listed company that engages in the meat business is the military-owned Fauji Meat Ltd, which has been struggling to turn a profit since it was created in 2016. The company witnessed a net loss of Rs1.3 billion in calendar year 2018, virtually unchanged from a similar loss it experienced in 2017. The company’s revenues actually shrank by 9.9% during the year.

Part of the problem has been simply trying to achieve scale in a market that is so fragmented. There are hardly any cattle farms in Pakistan that have more than 1,000 heads of cattle. This compared to countries like Brazil and the United States, where a single farm can often have over 1 million heads of cattle.

This lack of concentration of the animal population has proved to be quite a challenge: despite its proximity to the wealthy yet food production-starved Gulf Arab states, Pakistan’s share of the protein intake of those states is far behind its competitors. Brazil, from the other side of the planet, is able to sell several orders of magnitude more meat to the Gulf Arab states than Pakistan, which is less than a week’s sailing time from every single major port in the Gulf.

For their part, the government of Punjab and Sindh in particular have sought to encourage greater investment in the sector, providing all sorts of incentives and infrastructure, including subsidies on feed and veterinary care for animals being reared for export.

And lest one think Eid might be an issue, it is not: the 8 million animals sacrificed during Eid represent a small fraction – less than 5% of the more than 160 million heads of livestock in Pakistan.

The poor farmers in Sibi could certainly benefit from Pakistani beef being consumed in the nearby food-starved markets of the Gulf Arab states. For now, however, they mostly make do with the patronage of men like AKD.

Well explained. Loved every bit of it.

please note there is not a single usd billionaire in pakistan.

also estimates of net worth of mr aqil karim dhedi are just estimates and nothing else.

certainly he is not net-worth @ pkr 160 billion rupees

nobody in pakistan is

“The only publicly listed company that engages in the meat business is the military-owned Fauji Meat Ltd, which has been struggling to turn a profit since it was created in 2016”

Meat One, is also traded on the PSX as Al-Shaheer.

Comments are closed.