Pakistan is an agrarian economy. This little factoid is drilled into our heads from our earliest school days. It is plastered front and center in social studies books, and is most likely the first thing you learn about Pakistan’s economy and topography. This agrarian bent, along with an inexplicable pride in being rich in natural resources (as if that sets Pakistan apart from the rest of the world), goes to the core of how we try to portray ourselves as a country.

Behind all the bluster, behind the terrors and blacklists and nuclear arsenals, there stands the folksy farmer. He wakes up with the sunrise, ploughs his field, feeds his cattle, wistfully roams his fields and takes in the fresh air. Disconnected and unconcerned with all of the chaos of the city, it is a good, simple life.

The largest concern that this noble farmer may have to face at some point is a low crop yield, and that too is easily fixable. Get a bag of urea fertilizer, sprinkle a little here, a dash there and another handful there, and watch as it works its magic.

At least that is how the television and radio ads make it look like. One farmer tells another of how his crops have done magically well thanks to this new fertilizer. The other is shocked but intrigued, prompting the former to explain the details of the how the magic of urea has changed his life and fortunes, and the latter scurries off to buy said fertilizer. For good measure, we sometimes even get a shot of farmers dancing off into golden hour as they spread the fertilizer in their fields to the beat of flute music.

As ad nauseam as the fertilizer industry’s advertising has become, the fact of the matter remains that access to fertilizers can often be a life changing factor in the lives of farmers, especially those working on a small scale. As such, there is no surprise that fertilizer is one of the most subsidised products in the country, and for good reason.

A staggering 39% of our labour workforce is employed in the agriculture sector, 66% of the population depends on the agriculture sector for its livelihood, it makes up 19% of our GDP, and makes up 20% of our exports, not including the input it provides for the textile industry, which makes up for 60% of the country’s exports.

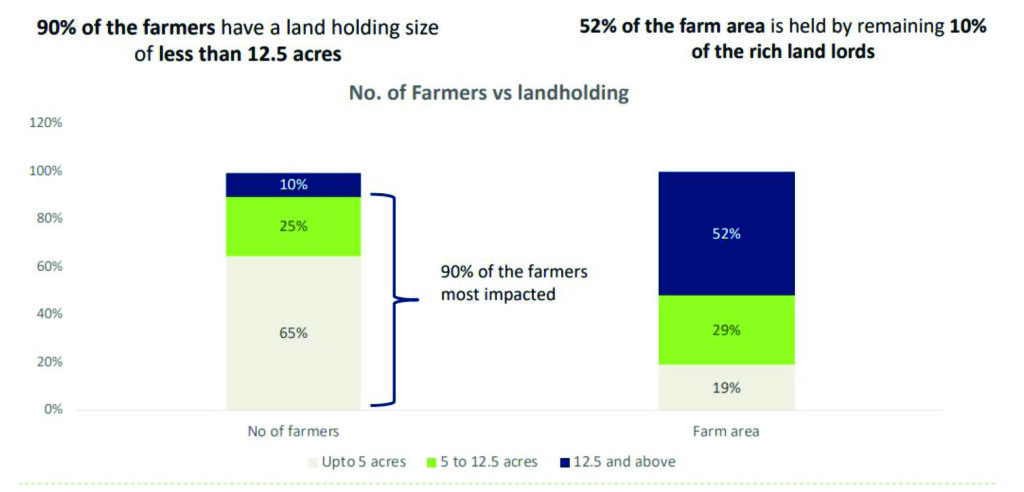

But while two-thirds of our population may be dependent on the agricultural sector for their livelihood, the sector is also one in which Pakistan’s wealth gap is most palpable. According to the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), a mere 10% of zamindars hold 52% of the agricultural land in Pakistan.

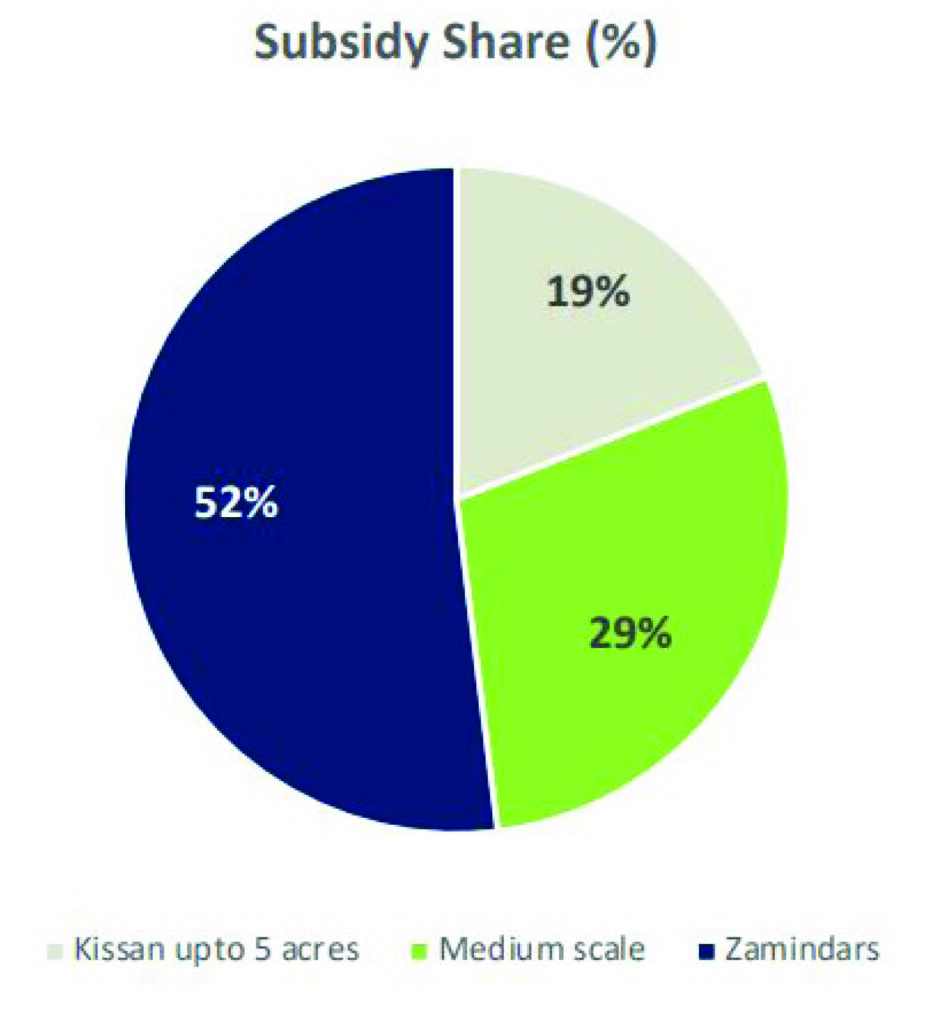

Currently, we employ an across-the-board subsidy on Urea import that is costing tens of billions of rupees, and hurting both the country’s balance of payments and fiscal deficit. It also means that the richest farmers with the largest land holdings reap most of the rewards from these billions that the government is pouring in.

But short of land reform, how can the government ensure a more equitable dispersal of the fertilizer subsidy? Would incentives to the local industry work, and are the fertilizer companies to be trusted? Most importantly, could changing the subsidy framework do anything to actually add some credence to the image of the happy-go-lucky farmer cultivated by textbooks and peddled by years of advertisements?

The state of the sector

From whichever angle you approach the problems of a sector, the macroeconomic determinants will remain the same. With the agriculture sector, one could look at more specific issues such as low crop yield, shrinking agri acerage, low margin crops and poor farm economics. But these are issues that have existed, will continue to exist and can be dealt with at a more opportune time.

What is plaguing the agriculture sector is the same thing haunting every other sector: interest rates have almost doubled from 8% to 15%, the Pakistani rupee has depreciated by 30% in the last year alone, inflation has more than doubled from 5% to 12%, and the prices of utilities such as gas are also on the rise.

As a result of devaluation, farmers face the brunt of the rising inflation and input costs as well as increased prices of utilities and energy costs. Naturally, this results in higher food prices, which heightens the country’s food security issues, and so on and so forth goes the deadly cycle.

To its credit, the government seems to have picked up on the fact that the sector is important. Currently, the federal government has 13 projects in the pipeline on which they are spending Rs 290 billion under the five year National Agriculture Emergency Programme. The federal government’s five year plan taking place with the coordination of all provinces is aimed at boosting crop yield, fishery and livestock development as well as water conservation of a little less than combined live water capacities of Tarbela and Mangla dams.

The provincial allocation to agriculture has naturally also seen a similar rise, with a total Rs 114 billion allocated for agriculture projects in the provinces. The Punjab provincial budget saw a 24% increase given to the agriculture sector, while the KP development budget saw a 63% increase. A Rs 8.4 billion allocation has also been made in the Sindh budget.

Part of the current government’s agriculture vision was the provision of a ‘smart subsidy’ that would provide agricultural inputs to 3 million small scale farmers that have farms up to a maximum of 5 acres, as explained in the PTI’s 100 day agenda. The plan was as ambitious as any of the other agenda’s on the PTI’s plate for the first 100 days. By July 2019, they were supposed to have already set up mechanisms to monitor the schemes, and made the first round of payments to farmers and vendors using digital platforms. It is now November, and the government has still not developed their basic scheme, which was a goal they had set out to achieve by March.

The state of the subsidy

The PTI’s desire to provide a smart subsidy to farmers with less than 5 acres of land is a proposition that makes sense.Given the wealth gap and disparity in land ownership, and across the board subsidy would mean an equal but inequitable distribution of government assistance.

In the current dire economic straits, those most adversely affected, as is always the case, have been the poorest farmers with the least land to their names. With 10% zamindars holding 52% of the land, the remaining 48% of the land is divided among the remaining 90% agriculturalists. These 90% farmers all have land holding sizes of less than 12.5 acres as per PBS data. Out of this, 65% of the farmers have even smaller land holdings of less than 5 acres per farmer. The 10% zamindars that own the most land would thus get 52% of any across the board national subsidy, while medium scale farmers with farms between 5 acres to 12.5 acres would get 29% of the cut. The smallest farmers that own less than 5 acres of land would only get 19% of the government subsidy.

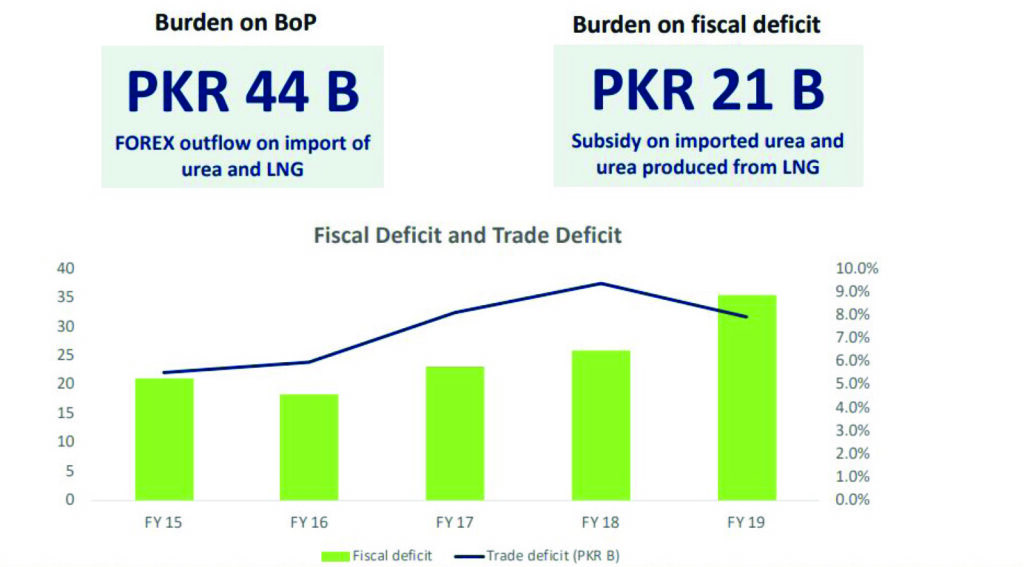

A major example of misdirected government intervention in the fertilizer industry is in the subsidy and import of urea. Domestic urea demand hovers somewhere around 5.8 million tons, while the domestic supply using indingenous gas peaks at 5.5 trillion. The remaining demand for 0.3 million tons of urea is met with expensive urea imports, or the production of urea using imported gas such as LNG.

The foreign exchange outflow on the import of urea and LNG is a Rs 44 billion burden on the balance of payments. But the problem does not just end there. Once the government imports either the urea or LNG to produce the urea at home, the costs have racked up so high that they cannot compete with the prices of the urea being produced domestically using indigenous gas. This means the government then has to subsidise the imported bags of urea and the urea produced using LNG, which puts a Rs 21 billion burden on the fiscal deficit.

In addition to this, the LNG provision to fertilizer producers is resulting in overflowing inventory. The government currently supplies 70mmSCFD of LNG to fertilizer plants, which has resulted in the production of 0.9 MT to date this year. The closing inventory of LNG based production as of October 15 2019 was also 0.7 MT.

Enter Engro

Earlier in October, Engro fertilizer held a closed door meeting with a select few journalists. Engro fertilizer’s Chief Financial Officer (CFO), Imran Ahmad, presented many of the same facts and data that have been discussed in this report.

The purpose of the meeting as per Imran Ahmad, was not to tell Engro’s side of the story, but to make a case for the farmers. These are our customers, he said, and it is our duty as a responsible organisation to look out for them when the government is not acting as efficiently as they could to give benefits to the most disadvantaged.

Every time a large corporation claims they are standing up for the little guy, one should take it with a heavy dose of salt. All CSR programmes, and Robin Hood missions by corporations looking to make even more money are most probably just that, a way to make money.

But even as Imran Ahmad explained Engro’s proposal with the socialist zeal of college graduate fresh out of University with a sociology degree, it became apparent what Engro was suggesting. That the Rs 44 billion in foreign exchange being spent to import urea and LNG to produce urea be instead directed towards the local industry. That they be provided the low grade gas they were promised, especially since the domestic industry could more than fulfill demand using gas at home if they were provided it. Let us at least look at the claims that Engro is making.

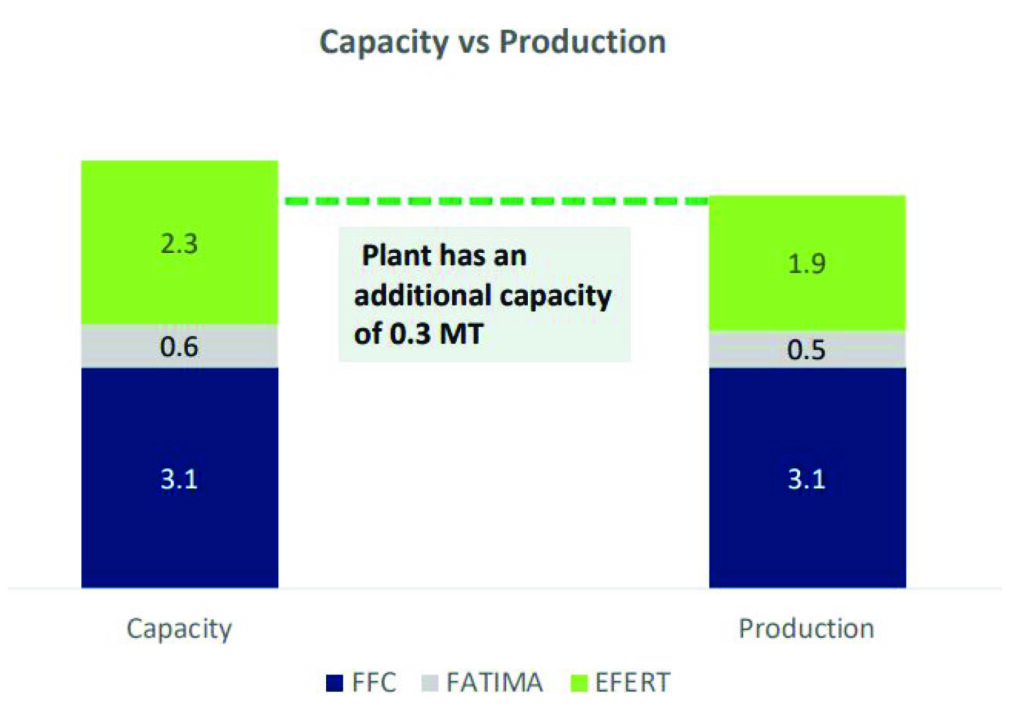

For starters, the local industry is currently producing 5.5 million tons of urea, while the demand can go up to 5.8 million tons. Of the 5.5 million tons being produced, Fauji Fertilizer is producing 3.1 million tons at full capacity, Fatima Fertilizer is providing 0.5 million tons, and Engro is providing the remaining 1.9 million tons. Both Fatima and Engro are unable to produce at full capacity.

If they were allowed to do so with the provision of gas, Fatima could produce an additional 0.1 million tons and Engro could produce an additional 0.4 million tons, meaning total domestic production using indigenous gas could go up to 6 million tons – 0.2 million more than the maximum demand.

Moreover, if the Rs 44 billion being spent in foreign exchange on the import of urea and LNG to produce urea were to be diverted towards subsidising bags of urea, an across-the-board subsidy of that amount would mean that the price of a single bag of urea would come down to a mere Rs 1690 per bag. Currently, a bag of urea costs Rs 2040 – a change of Rs 350 per bag.

Moreover, a more targeted subsidy could even mean that a lot of the poorest farmers could possibly get bags of urea for free.

According to Engro’s calculations, if Rs44 billion being spent on fertilizer import is used smartly, the government could even provide free urea to the smallest, poorest farmers in the agricultural diaspora. Farmers that own holdings up to 5 acres can get free urea in this money, and if the ceiling is increased to holdings of up to 12.5 acres, the government could provide urea at a discount of Rs860 at Rs1,180 per bag compared to the Rs2,040 per bag it is currently going for.

The smart subsidy system being encouraged by Engro would be a sticker-based subsidy mechanism, executed through a web portal which would enable fertiliser marketing companies to generate unique codes for their products. Under this system, farmers could redeem 25 bags per CNIC and the remaining subsidy proceeds could be dispersed into the farmers’ easy paisa account. The system has already been quite successfully implemented for phosphates in Punjab.

The numbers may sound too good to be true, but those are the numbers. Engro is also not a saint in this situation, and they have their own motives for these suggestions, but they do also have a reputation for being a responsible corporation. In his conversation with Profit after his presentation, their CFO Imran Ahmed continued to say that Engro was insistent on investing in Pakistan further, despite the bad hand the government has at times played them and proven again and again that they are not a good partner.

“one should take it with a heavy dose of salt” is exactly how Engro’s initiative should be taken, since they are provided the local gas at a subsidized rate. That is the same sort of subsidy they want to abolish at the farmer’s end. Where is that analysis in the whole equation? They have raked million and million of dollars at the behest of farmers. They have used farmers and their plight for their own interest and i wonder why no one is fact-checking Engro. I guess what they have absolutely and successfully done is to only market their side of the story. Kudos to them on such achievement and kudos to the writer who has thankfully put disclaimers in his article. I wonder how many of these “closed-door ” meetings engro does for their propaganda, which we don’t even know about.

Comments are closed.