They are called loosies in the United States. A single cigarette that is purchased and sold, usually in areas that are low-income and predominantly African-American. It is the lowest rung of dealership, and what can at best be called a ‘side hustle.’ But nothing seems to ruffle the feathers of the Goliaths at Big Tobacco more than a few loosies being sold on the streets and in department store parking lots.

Ask the tobacco companies, and they will holler and howl over how the the high taxation on their products result in smuggling, the proliferation of loose cigarettes, and what they claim is resultant criminal activity. Pakistan does not have a problem of cigarettes being sold out of trench coats on street corners and down dark alleys, but the tobacco industry still has the same complaints: high taxes and smuggled products.

Econ 101

In very plain, A-level, Economics for-Dummies terms, tobacco is a demerit good. It harms the health of the consumer, it is addictive, it harms those that do not smoke as well through passive smoking and its use should be discouraged by government. This discouragement can be carried out through health warning labels and curbs on advertising, but most importantly, through taxation.

But of course, where the taxation is supposed to help wean people off cigarettes, the addictive nature of the good means its demand is inelastic, and the government just ends up making a pretty penny out of taxing cigarettes. The contribution that the industry makes to Pakistan’s national exchequer every year is quite significant.

The tobacco industry in Pakistan is an imperfect market, with two players taking up 90 percent of the market share, their contribution to taxes in the form of Federal Excise Duty (FED) and General Sales Tax (GST) is enormous. These two players are Pakistan Tobacco Company (PTC) and Philip Morris Pakistan Limited (PMPK), and together they paid Rs 117 billion in taxes in the fiscal year ending June 2019. Since then, in the third quarter of the calendar year 2019, PTC has further contributed Rs 14.5 billion in excise duties and Rs 4.2 billion on sales taxes, while PMPK has added Rs 2.76 billion in excise duties and Rs 820 million in sales taxes. Despite such significant numbers – nearing 3 percent of the total tax revenue for the government – so far the Tobacco industry has been paying taxes on what it declares it to be the final production and sales. In terms of taxation, FBR relies on “self-assessment” by the manufacturers.

According to a report released by Social Policy and Development Centre (SPDC), “Quantifying the Potential Tax Base of Cigarette Industry in Pakistan”, the problems in the tobacco industry reach far beyond smuggling, and expands in the myriad of ways that the industry is underreporting production and sales, while it may also be adding new accounts in their financial statements to cover up some of these underreported profits.

This self-assessment has led to an approximate loss of Rs 15-20 billion per annum for the national exchequer, and that too for an industry that continues to poison its customers. but the industry players seemed to have had their interests protected so far. For one, they have their representatives in the legislature, and by that we do not mean lobbyists, but parliamentarians that have stake in tobacco. The former KP Health Minister, Sharam Khan Tarakai, comes to mind, whose family are some of the biggest names in the country’s tobacco industry.

At the launch of this report by SPDC, FBR’s Member Inland Revenue policy Dr Hameed Ateeq Sarwar said that the tobacco industry has representatives within the National and Provincial Assemblies which makes it harder for the tax collection authority to implement stricter laws.

It could be coincidence, but in June 2019, it was feared by farmers that a Rs300 tax per kilogram on tobacco by the Federal Bureau of Revenue (FBR) would render a large number of farmers and industrial workers jobless, and bring huge losses to the growers and those associated with this cash crop in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. When the farmers complained, Tarakai was part of the high power government delegation that assured them that the FBR would impose the tax on smokers, according to Abrarullah, President of the Mehnat Kash Labour Federation.

But when the tax was finally implemented in the budget, the weight was falling on the farmers again. It was a neat situation for the tobacco companies and the government alike. The former did not see a dip in demand due to high prices, and the latter still got their cut in the war of taxes. The ones to suffer were the farmers, who claimed that a well-organised effort is being made by influential people in the country to force the farmers in KP to either stop growing tobacco or sell the produce to two multinational tobacco companies in Pakistan.

The News International, even went so far as to reporting that the government added Rs300 tax on tobacco after senior officials of the multinational tobacco companies met some top officials a day before the budget.

Smuggling is bad, what is being done?

While the government and the tobacco industry might bicker, and maybe even collude on and off, on taxation issues, the one thing that both agree about is that smuggling is a big no. Smuggled product cuts into the tobacco companies’ market, and means tax free cigarettes rob the government of revenue, and promote lawlessness. But again, does Pakistan really have a loosies problem?

After years of complaining and persistent badgering from Tobacco companies to crack down on smuggling coupled with Pakistan’s continued failure to implement the World Health Organization’s (WHO) obligations from Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), the FBR has introduced a new Track and Trace system.

The new system looks to eliminate smuggled cigarettes, and the FBR has also licensed a consortium including National Radio Telecommunication Corporation (NRTC) for a mobile app that will monitor production and transportation of cigarettes.

But this new effort is trying to do something far more important than curbing the less pressing problem of smuggled cigarettes, and also looking into the production side of the tobacco companies. The FBR’s new policies track and trace system will be aiming directly at finding out the actual output of tobacco companies. However, even with that it might not be possible reveal and capitalize on the full tax potential of tobacco industry. For starters, a few players have already moved their operations to one area where track and trace system does not exist – Azad Kashmir (AJK), to escape the writ of FBR, as was told by Dr Ateeq himself, not to mention the erstwhile FATA areas have also been used for the same purpose.

The earlier mentioned SPDC report highlights just that, as it also identifies correlation in certain trends in reported production and the addition of new headings in the financial statements of both companies – which might as well be a coincidence – to the changes in FEDs as applied by the government. SPDC claims that unless an integrated information system is put in place that monitors the process of tobacco industries at all three stages – production, wholesale and retail – the room and incentives for tax evasion are likely to continue.

The state of affairs

To begin understanding the situation, let us look at the problems identified by the report, the evidence available otherwise that corroborates the report, and the proposed and actual measures being taken by the government in this regard.

As per, Oxford Economics – a global forecasting and quantitative analysis company, and Euromonitor International – London-based marketing research firm, approximately 37 billion non-duty-paid cigarettes are consumed in Pakistan each year, out of which 27 billion are produced domestically. This ratio suggests that the underreporting, or perhaps non-reporting, cigarette production is at least 2.7 times a bigger issue than smuggling. As per Euromonitor’s finding, approximately 34 percent of cigarettes consumed in Pakistan in 2018 were non-duty paid.

[To put this in perspective let’s say that every year an average 30 percent of production goes unreported. By this number, the Rs 117 billion collected in the fiscal year 2019 would be only 70 percent of the total production, meaning an approximate loss of Rs 50 billion annually. Since, if the total production was reported and taxed, the collection would be approximately Rs 167 billion.]

There is enough data in usual newspaper reports that such underreporting is occurring in the country, sometimes blatantly, sometimes through loopholes, and sometimes by influence. In 2017, Business Recorder reported detection by a Rawalpindi tax office of tax evasion by Phillip Morris. In December 2018, Policy Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) released a report “Economics of Tobacco Taxation and Consumption in Pakistan” that substantiated a loss of Rs 36 billion in fiscal year on account of moving from a two-tier FED regime to a three-tier regime.

As opposed to outright eliminating of reporting production, this instance is one of a legal loophole, since the tobacco companies moved their bestselling brands to the lowest tier to avail a 50 percent cut in FED. 2019 saw another episode where the tax evasion went right to the roots of tobacco, literally. This was the FBR imposed adjustable tax of Rs 300 on green leaf processing mentioned earlier in the story that had farmers complaining left, right and center. This was supposed to be a corrective measure to the estimated non-documented 40 percent tobacco leaf purchases in Pakistan. However, coming full circle the parliament voted it as a move against poor farmers and therefore a month later, in June, the move was reversed.

The instances mentioned above are fairly recent but the problem and its realization are much older. As far back as 2005, FBR had tried to stamp each cigarette pack to monitor sales from the formal sector but due to the severe opposition from the industry it never got down to implementation. Likewise, System of Electronic Monitoring of Production (SEMP), not much different to the current track and trace system, was also proposed in 2014 by FBR, which also saw the same fate as their 2005 initiative. Since 2017, FBR finally buckled down on T&T which is now finally in its final stages of implementation, but its results are yet to be seen.

The numbers

The SPDC report has taken time series data from 2004 till 2018, for PTC, PMPK, and a third company, Khyber Tobacco Company (KTC) to evaluate how the reported production and corresponding profits have changed for these players over time, and how the foremost claims of rising cost of sales from these players might not be as significant for their revenues as these companies would want the regulators to believe.

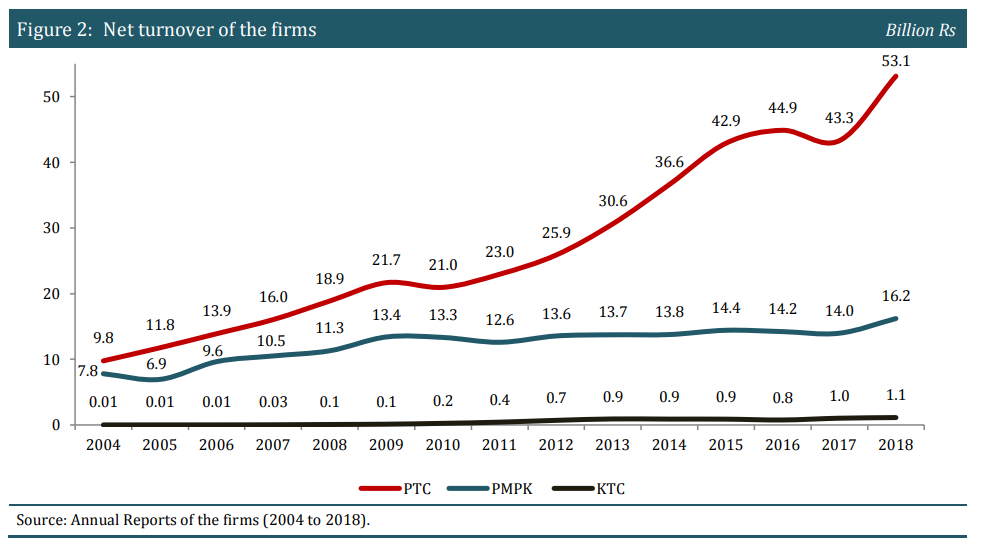

One of the trends spotted by the report through this data is the four-fold increase in the size of the industry from 2004 to 2018, with the turnover of both market leaders dropping in 2017 for the first time in a decade and a half. As the report also mentions, while this may be a coincidence, it does have a direct link with the rates of FED. During the same time, PTC seemed to have added 19 percent to its market share, from 56 percent in 2004 to 75 percent in 2018, taking all of it from PMPK.

Moving on to the cost side analysis, all three companies showed nominal increase in the cost of sales but it continued to fall short of the increase in the turnover reported by all three companies. the notable point however might be the steepest rise in cost of sales in the year 2018, which was attributed to the deteriorating Pakistan Rupee in the international market – thereby signaling a heavy dependence of these companies on imported inputs.

Another factor highlighted by the report is that while the year 2017 saw falling revenues as well as scaling down on its workforce, the cost of sales for both PTC and PMPK went up. Interestingly 2017-18 was also the time when FED on several brands of cigarettes was reduced from Rs 32.98 to Rs 16.

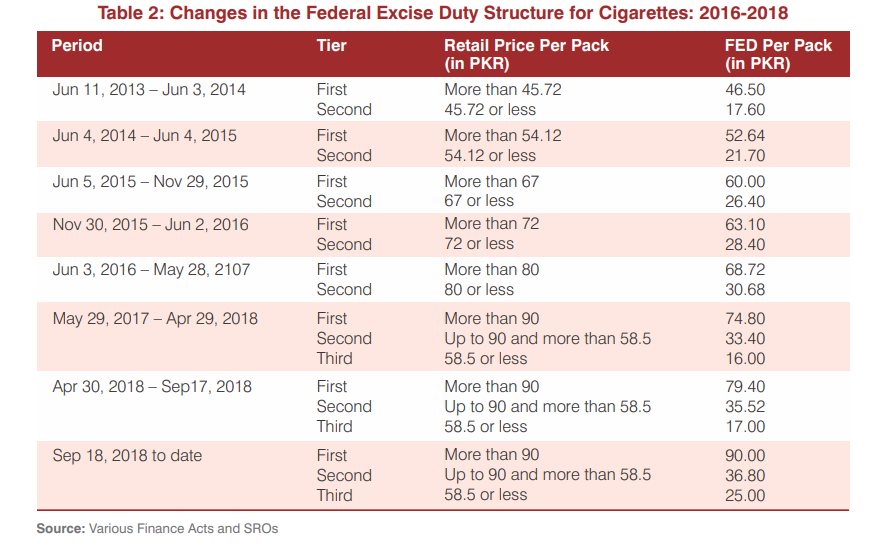

To look into FEDs in depth, the structure of the FED on cigarettes has historically been a complicated mix of a specific tax on low-priced brands, an ad valorem tax on high-priced brands, and a combined specific and ad valorem tax on mid-priced brands. In 2013, the ad valorem tax was withdrawn, and a two-tier structure of specific taxes based on the range of retail prices was introduced. Changes have been made in the tier structure and tax rates since then. These tax policy interventions have often generated debates about whether the objective of taxation on cigarettes was achieved or not. A table from PIDE’s report is also attached for further clarification on changing FEDs in the past few years.

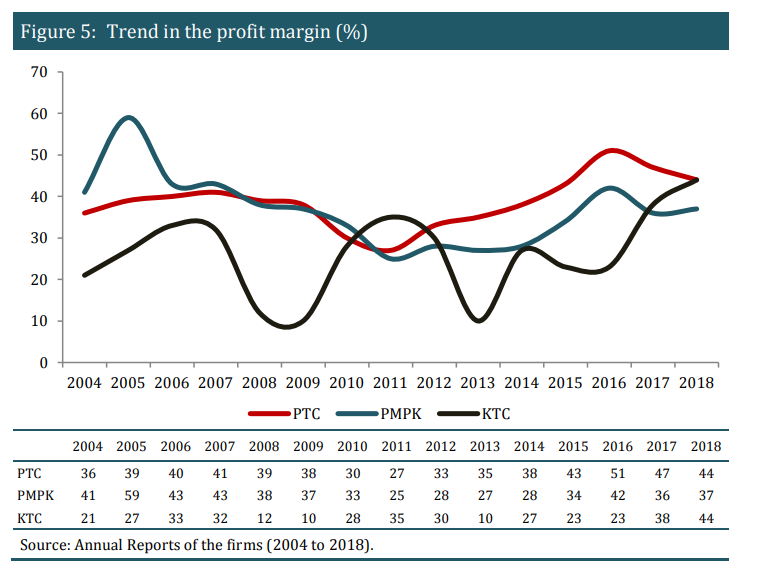

Taking another excerpt from the SPDC report, one might gauge the tobacco companies’ claim of higher FEDs causing reduction in their sales and therefore profitability. The picture that the numbers paint, however, shows that profit margins seem to stay the same and even increase with higher FEDs and somehow with lower sales as well. “For instance, during 2010 to 2014, the profit margins of PTC, PMPK and KTC hovered around 32 percent, 28 percent, and 26 percent, respectively. However, profit margins substantially increased afterwards. In fact, in 2017 – a year of substantial decline in production – profit margins were 47 percent, 36 percent, and 38 percent for PTC, PMPK, and KTC, respectively. Even in 2018, profit margins of PMPK and KTC were at a higher level, and PTC’s did not drop significantly,” the SPDC finds.

Tricks of the trade

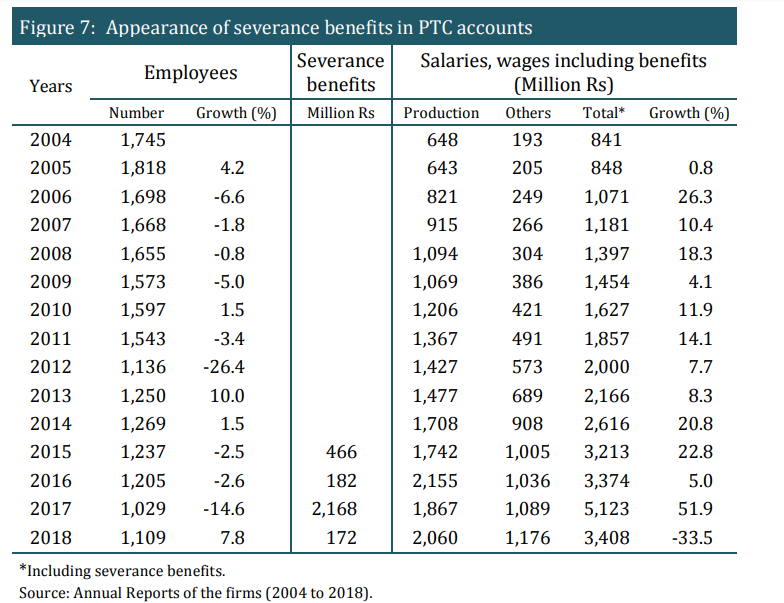

Certain things, however, may be ‘hidden in plain sight’. This method of tax evasion by the PTC and PMPK involves the addition of new headings in financial statements. While one may brush this off at first glance, a deeper look into how these values are calculated is enough to raise suspicions. The report highlights, PTC has introduced a new category named ‘Severance Benefits’ in 2015. Severance benefits refer to an amount paid to employees who leave employment unwillingly. This category is in addition to the category, namely, salaries, wages including benefits. It is very unlikely that the company did not pay severance benefits prior to 2015. Whereas, it is probable that severance benefits were clubbed into wages and benefits and the new category could be an outcome of improvements in financial reporting of the company.”

There was a drastic reduction of 26 percent in the company’s work force in 2012, but severance benefits are not mentioned. After 2015, severance benefits are shown as a regular expense with varied amount. For instance, even in 2018 when the company’s workforce grew by almost 8 percent, company paid Rs 172 million under severance benefits. The report says that this category is also important because the estimation of this number is based on financial data of more than two decades, which means that even if these were part of salaries and wages prior to 2015, then ignoring this cost after 2015 would mean that even the extent of under-reporting has been underestimated.

On PMPK side, the new category that raised its head in 2015 was ‘Trade Discounts. Before this category was part of the company’s financial statements the net turnover simply turned out to be the difference between gross turnover and taxes, but now this number is also subtracted from sales in addition to FEDs and GSTs. The fact that from Rs 244 million in 2015 these trade discounts exceeded Rs 1 billion in 2018 is, at the least, a cause for wonder.

So one might take three points from this discussion: 1) Lower FEDs do not necessarily mean higher sales, as lower sales also do not mean lower profit margins. 2) Cost of sales might not have a lot of impact on net sales. 3) Two major companies decide to add new categories to their financial calculations in the same year.

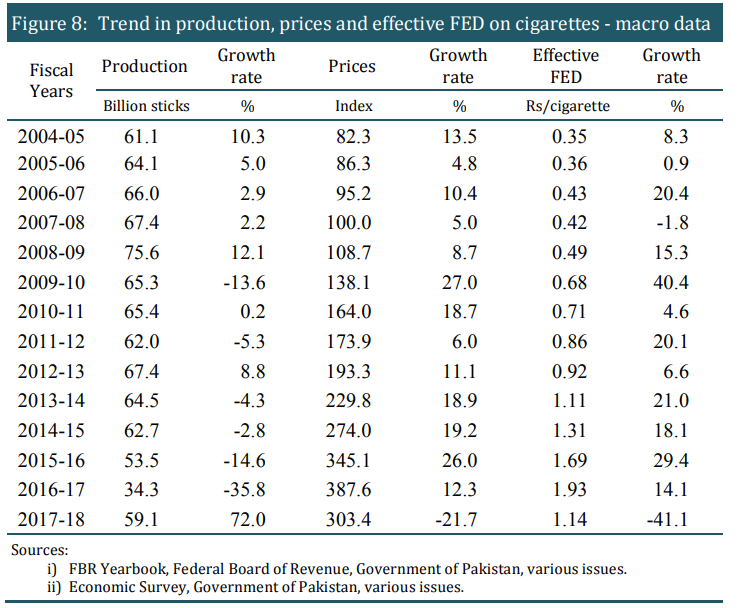

Now moving on to the exact, possible relationship between FED and the production/reporting of cigarettes as identified by SPDC in their report.

One cursory look at the numbers would show that the increase in FEDs did not lead to a corresponding increase in the final prices. While this may be explained through the possibility that the cigarette manufacturers absorbed some of these increases, the changes in the reported production are less easy to explain.

The report explains that “with the exception of 2008-09, the production of cigarettes remained fairly stable between 61-67 billion sticks until 2014-15. However, massive fluctuation in production is evident in the last three years. Declared production reached the lowest level in 2016-17 with massive decline of 36 percent. In absolute terms, the production of the industry decreased by 19.2 billion sticks in one year. This decline can be attributed to the consistent increase in prices of cigarettes largely due to the increase in the FED rate. In 2017-18, the federal government introduced a three-tier FED structure – with a new tier for the low-priced brands. The effective FED rate was slashed by 41 percent, which resulted in a 22 percent reduction in the prices of cigarettes. Interestingly, this decline in prices corresponded with a massive growth of 72 percent in production of cigarettes. In absolute terms, production bounced back to almost 60 billion sticks. This peculiar trend in production of cigarettes coinciding with the variation of the FED raises concerns over the validity of declared production.”

Based on the above trends, and after running the financial data through a supply side and demand side econometric functions, the SPDC report, suggested the following: Link the FED with multi-stage taxes, link financial data with production, and reduce seasonality in production. This last suggestion comes in the wake of the trends observed that the projected quantities of cigarettes produced shoot up right before the federal budget, perhaps because of the sole reason of uncertainties associated with tax policies. A medium-term tax policy might also serve to reduce such underreporting.

As with the current mechanisms being put in place, FBR hopes to collect around Rs 200 billion from the tobacco industry in the next three years with a single tier of FED. While the tax collector might want to keep tax collection tier-free, there is a possibility that the rate of taxes will be increased. However as per Dr Ateeq, that decision is put on hold as not to scare the formal sector.

At the same time, while the track and trace system might be able to provide a better insight into production volumes, the data from smaller units, especially those who have already relocated out of FBR’s writ might be difficult. It also poses a threat of larger companies starting operations from smaller factories – which if happens will not be a new practice, as several such units have been uncovered over years still operating after they were formally reported to have been closed down. The Rawalpindi incident with PMPK was of the same nature.

At the end of the day, the implementation of GST collection at several levels might be the ultimate solution to the problem of underreporting and tax evasion. At present FED is collected at factory level on declared production. If the FED is linked with GST and then GST is collected at three stages – factory, distributors, and wholesalers/retailers, coupled with track and trace system keeping in view the production and transportation from the formal sector, it might bring an end to this decades long practice of tax evasion.

[…] Pakistan Today Profit […]

[…] How Pakistan’s Big Tobacco gets away with tax theft – Pakistan Today […]

Comments are closed.