Eight years ago, it looked like it was over.

On March 17, 2012, a story appeared on the front page of The Express Tribune, breaking the news that Citibank Pakistan was about to sell off its retail banking division and drastically shrinking its physical and financial footprint in the country. And in the next few months, that is exactly what happened. In November 2012, Citibank announced that it would sell its credit card and consumer lending portfolio to Habib Bank Ltd.

Citibank had already sold off its mortgage lending portfolio to BankIslami Pakistan in 2009. So, the news that it was completely shutting down its retail presence sounded a lot like a prelude to the bank shuttering its presence in Pakistan completely. This was less than four years after the global financial crisis began in the United States and shook the world.

And global banks were exiting Pakistan at the time. RBS Pakistan, which had acquired ABN Amro’s assets in Pakistan, sold off its operations in the country to Faysal Bank in June 2010. HSBC had announced its intention to sell off its Pakistan branches in early 2012 as well. And, at the time, it had become widely understood that Barclays was struggling in Pakistan and likely to exit the market entirely.

So the idea that Citibank might be thinking of exiting Pakistan – while still a shock – was not entirely inconceivable. Of course, Citibank management at the time issued the usual denials and statements saying they remain committed to the Pakistani market. But the market was highly sceptical.

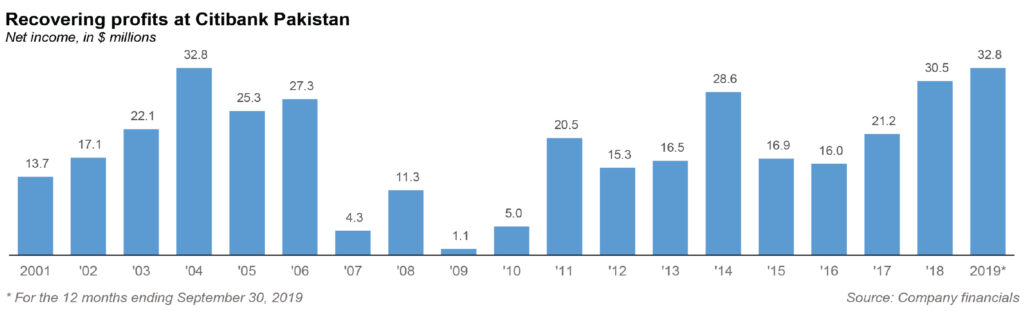

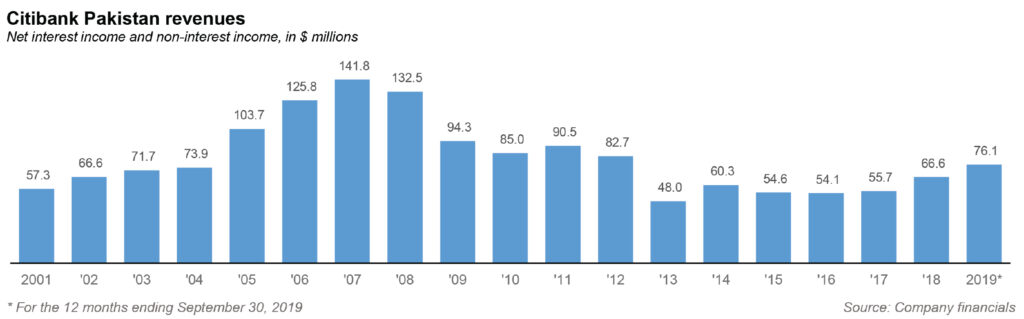

In the eight years since then, however, it turns out that the market was wrong, and Citibank management was correct: the global bank remains committed to its corporate and investment banking operations in Pakistan and – in 2019 – passed an important milestone: it earned higher profits than at any point in the last two decades, and likely in its history in the country.

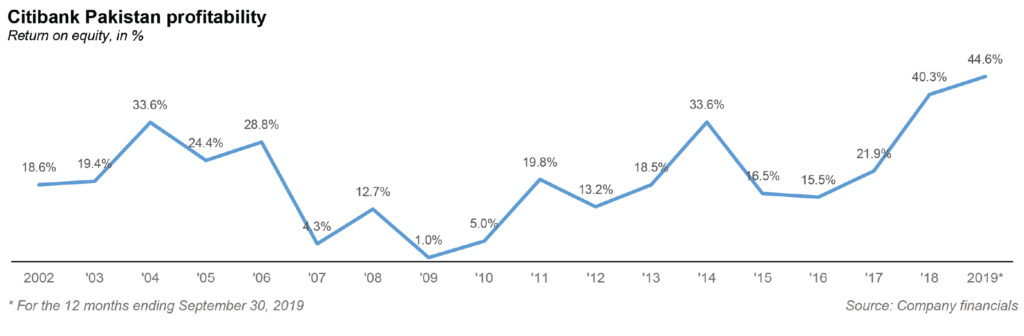

And its return on equity – the all-important measure of bank profitability – is higher than it has ever been over the past two decades for which data is publicly available. Despite accounting for just 0.7% of the banking industry’s deposits, as of September 30, 2019, the latest period for which financial data is available, Citibank Pakistan accounts for 2.5% of its profits.

And Citibank was able to do this by going back to its roots: a global corporate and investment bank, with a presence across most economies around the world, a connecting financial institution that forms part of the backbone of the global financial system.

Citibank’s unique place in Pakistan

There is perhaps no foreign bank that captures the Pakistani imagination more than Citibank. Despite being much smaller than its current rival Standard Chartered, Citibank seems to have produced more financial leaders in Pakistan than any other financial institution. In both Corporate Pakistan – as well as the government – it means something special to be able to call oneself an “ex-Citibanker”, more so than any other financial institution.

The bank’s alumni in Pakistan include two former federal finance ministers – Shaukat Aziz and Shaukat Tarin – one of whom (Aziz) went on to become Prime Minister. They also include two provincial finance ministers – Murad Ali Shah of Sindh and Hashim Jawan Bakht of Punjab – one of whom (Shah) went on to become provincial chief minister. While Shah and Bakht are both from politically influential families, Aziz and Tarin’s rise in the federal government was in no small part due to the stature they gained as being highly successful global bankers who spent a significant portion of their careers at Citigroup.

Why Citi, though? Of the world’s major financial institutions, many have had a presence in Pakistan, including Bank of America, Chase Manhattan (the predecessor to JPMorgan Chase), in addition to HSBC, and, of course, Standard Chartered. So why is it Citibank that is valued as the training ground for the country’s financial leaders?

There are two reasons why this is the case: Citi’s longevity in Pakistan, and its access to global capital markets and investors.

Citi’s path in Pakistan

Citi is not even close to being the global bank with the longest stretch of operations in Pakistan. That honour belongs to Standard Chartered, which has been operating in what is now Pakistan since 1863, when it opened its branch in Karachi, what was then its sixth branch in the world (the first five were in Calcutta, Bombay, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Singapore).

Having said that, Citi has certainly been around for a long time, having first opened a branch in Karachi in 1961 and having continuously maintained its presence in the country since then. That cannot be said of other global financial institutions, most of which have all left Pakistan by now, with very few exceptions. Chase Manhattan left in the 1980s, Bank of America in the 1990s, and JPMorgan and Credit Suisse tried in the early 2000s, but gave up within a few years and left.

But longevity alone does not account for Citi’s allure. If that were it, Standard Chartered would be Pakistan’s most admired foreign bank. What makes Citi unique is the fact that – among the major global capital markets players in the world – it is the only one that has a longstanding presence in Pakistan, and one that it has used in order to help the government of Pakistan gain access to cash from global investors for its bonds and to help Pakistani companies gain access to global investors.

In short, it is the only major global investment banking franchise with operations in the country. In this regard, Citi’s competitors in Pakistan are not Standard Chartered and Habib Bank. They are JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs, neither of which operates in the country at all.

Standard Chartered, while a London-headquartered global bank, does not have a significant presence in investment banking. It is a strong corporate and commercial bank, but not an investment bank. In the world of capital markets and investment banking, Standard Chartered shows up nowhere in the global league tables (essentially, a ranking of financial institutions by total investment banking revenue).

Citi, on the other hand, is consistently in the top 5, earning $4.3 billion in investment banking revenue in 2019, according to data from Refinitiv, a financial data provider owned by Reuters.

What does any of this mean?

It means that while Standard Chartered can use its rupee-denominated local deposits to buy local, rupee-denominated bonds from the government of Pakistan, if Islamabad wants to issue dollar-denominated bonds to investors outside the country, the only bank with a local office it can talk to is Citi. (Technically, Deutsche Bank has also been a global investment banking powerhouse, and has offices in Pakistan, but its global investment bank has effectively self-immolated, so the less said about that, the better.)

And this is not just a theoretical capability: it is one that Citigroup has actively cultivated, having served as the government of Pakistan’s investment banker on nearly all global bond issuances, and several privatisation transactions as well.

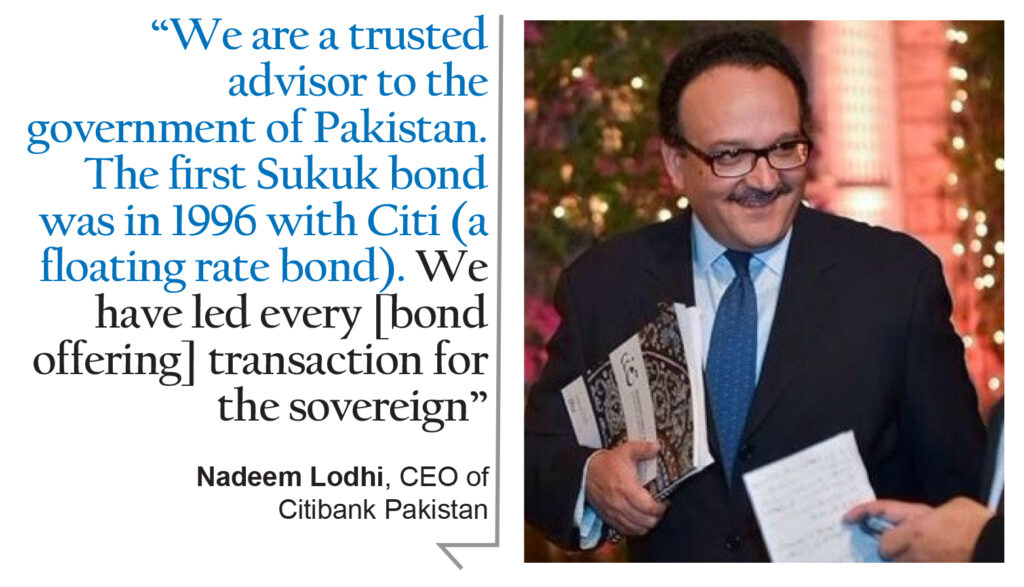

“We are a trusted advisor to the government of Pakistan. The first Sukuk bond was in 1996 with Citi (a floating rate bond). We have led every [bond offering] transaction for the sovereign,” said Nadeem Lodhi, CEO of Citi Pakistan, at a press event in Karachi in December 2019.

And it is not just the government of Pakistan. When it came time to sell their investment in K-Electric, the only investment bank that Abraaj Capital could realistically turn to was Citi, which had strong mergers and acquisitions advisory teams in both Europe and the Asia-Pacific regions, where Abraaj was most likely to find buyers. Citi was awarded the mandate to serve as the sell-side advisor to Abraaj in the summer of 2014 and were ultimately able to find a willing buyer in Shanghai Electric. (The transaction has yet to close, but that is mostly due to regulatory reasons.)

Innovating for the Pakistani financial market

It is not just its ability to offer global investment banking services in Pakistan that has given then institution an outsize level of influence in the country. It is also the fact that a majority of innovation in Pakistani banking has come from Citi.

In the early 1990s, it was a team of Citibank executives that decided to re-invent the very notion of consumer banking in Pakistan, introducing products like credit cards, auto loans, and significantly expanding the scope of the country’s mortgage market.

At the time, the bank was led by Shaukat Tarin. “We practically invented consumer banking in Pakistan,” said one former member of Tarin’s team at Citibank. “Before us, nobody had heard of a credit card and there was hardly any mortgage or auto financing.”

This strategy led the bank to start expanding its physical presence in the country in the mid-1990s, opening up branches beyond the three in Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad to include other cities as well, ultimately taking its branch network in the country to 18.

That expansion beyond the three major metropolitan areas led the bank to expand its offerings and start localising them in somewhat unexpected ways. For instance, Citibank was the first bank in Pakistan to start issuing cheque books in Urdu. It created Pakistan’s first 24-hour customer service center. And it basically invented the concept of “priority banking” for high net-worth clients in Pakistan.

It was able to be that innovative in large part because of a unique culture that the bank was able to foster among its employees, who felt a fierce loyalty and sense of ownership about the institution and the businesses they were building within it, almost as though the bank itself was just a platform for their own entrepreneurship.

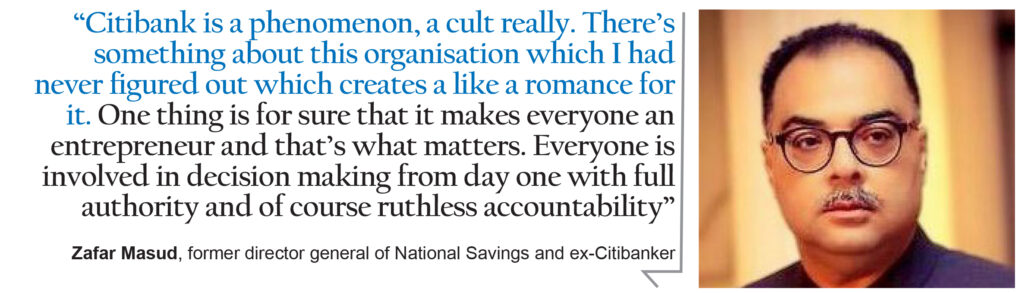

“Citibank is a phenomenon, a cult really,” said Zafar Masud, a former Citibanker who has served as the director general of National Savings. “There’s something about this organisation which I had never figured out which creates a like a romance for it. One thing is for sure that it makes everyone an entrepreneur and that’s what matters. Everyone is involved in decision making from day one with full authority and of course ruthless accountability.”

All of those developments in the early 1990s began to truly pay dividends in the early 2000s, which was likely the heyday of Citibank Pakistan. By 2002, Citibank accounted for 2.7% of total banking sector deposits in the country, but 8% of the sector’s profits. (Admittedly, this was in large part due to the fact that the major banks in the country were still mostly state-owned and only just coming out of their decades of loss-making that began with former Prime Minster Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s disastrous nationalisation policy of 1974.)

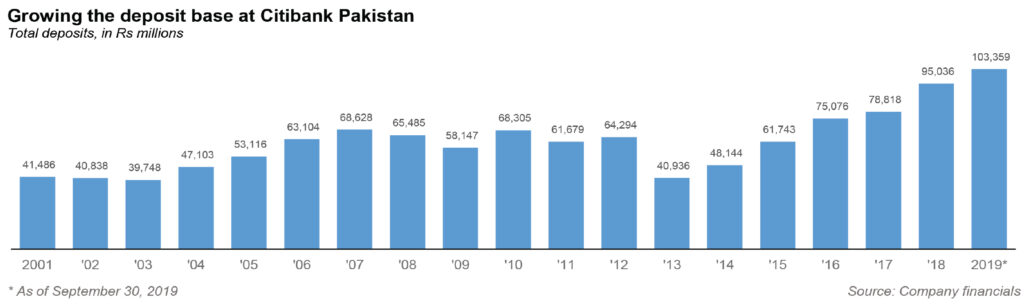

The peak for Citibank Pakistan in terms of size came in 2007, when it grew to have $1.1 billion in deposits and $1.5 billion in total assets. In terms of profitability, its best year was 2004, when the bank earned $32.8 million in net income. Return on equity that year hit 33.6%, an impressive level even by the heady standards of the pre-crisis era.

(A note on return on equity calculations: at Profit, we calculate return on equity by dividing net income for a period by the total equity at the beginning of that period, or the end of the previous period. We understand that the convention is to use the average of the equity over the period in question. However, it is our contention that using beginning equity is a more accurate reflection of the return on equity since it reflects the amount of equity capital available to the business before it started making those returns.)

At the time, the bank was led by Zubyr Soomro, a graduate of Karachi Grammar School and the London School of Economics, who had started his career in 1971 at Citibank in Karachi and risen by 1981 to become its first ever local head of corporate banking (previously, the position had typically been headed by an American).

After stints at Citi in Pakistan, the Middle East, and the United Kingdom, Soomro spent a little under three years as the Chairman and President of United Bank from 1997 to 2000 to help restructure the bank ahead of its eventual privatisation. He then returned to Citi as its country head in February 2000, a position he held for the next eight years.

(And yes, in case you are wondering, he is from the Soomro family: his father was former National Assembly Speaker Elahi Bux Soomro, and his cousin is former Senate Chairman Mohammad Mian Soomro.)

Fortuitously for Zubyr, he made the decision to retire when he reached the age of 60 in March 2008, a few short months before the global financial crisis devastated Citi’s operations worldwide, including in Pakistan. Unfortunately, his successor Arif Usmani had to deal with the fallout.

The post-crisis clean up

In many ways, what Citibank went through in Pakistan was not at all different from what the rest of the banking industry went through in the aftermath of the financial crisis. The difference, of course, was that Citi’s global home in the United States was also going through an extraordinarily difficult time that saw them having to accept a $45 billion bailout from the United States Treasury.

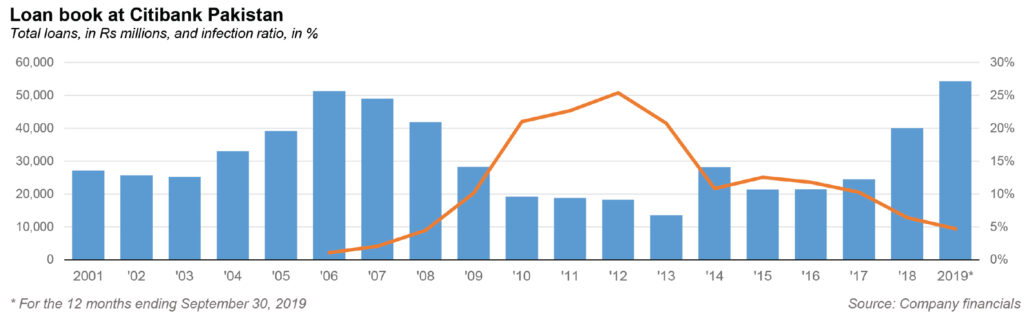

Nonetheless, the speed and scale of destruction on the balance sheet of Citibank Pakistan is breathtaking. In 2006, the bank’s infection ratio (bad loans as a percentage of total lending) was just 1.1%, a number that rose to 2.1% in the next year. By 2010, however, the infection ratio was 21%, and peaked in 2012 at an astonishing 25.4%.

With bleeding that bad, it is no surprise that Citi decided they needed to make a radical change. The bank began by selling off its consumer lending portfolio to BankIslami Pakistan in 2009, and then went ahead and sold its retail bank branches to Habib Bank in 2012.

At that point, with retrenchment to core markets (Pakistan has never accounted for more than 0.2% of Citigroup’s global profits), it would have been tempting to think that Citigroup might decide to sell the rest of its franchise and leave the country altogether.

Yet that is not what they did. Instead, they scaled back on the desire to revolutionise consumer banking in Pakistan and exited the business altogether, and began focusing on the bank’s roots: corporate and investment banking services to their large global clients, large local financial institutions, state-owned enterprises, and the government itself.

Citibank’s core business in Pakistan is its relationships with the local subsidiaries of large multinational companies (MNCs). “We are the market leader in the MNC space. About 70-80% of MNCs [operating in Pakistan] are banking with us,” said Amir Masood, head of multinational business at Citibank Pakistan, at that press event in December 2019.

That business includes not just deposits and loans, which the bank provides those clients, but also foreign currency exchange transactions, which are a lucrative business for the bank. In the 12 months ending September 30, 2019 – the latest period for which financial statements are available – the bank earned Rs2.7 billion in revenue from its foreign exchange business, which accounts for over 10% of the entire banking sector’s foreign exchange business.

Then there is the investment banking business, where the company advises clients on mergers and acquisitions. “First we helped Telenor buy Tameer Bank, and then we helped Ant Financial with their stake in Telenor Microfinance Bank,” said Nadeem Lodhi. “We also helped with the K-Electric sale to Shanghai Electric.”

The bulk of Citi’s revenue in Pakistan – about 62.5% – comes from old-fashioned deposit-taking and lending. While the bulk of Citi’s lending portfolio consists of government bonds, in which the bank is an active market-maker, its corporate lending portfolio has more than doubled over the past two years and stands at Rs54.3 billion as of September 30, 2019.

Most impressive, however, are two numbers pertaining to its profitability: net income for the 12 months ending September 30, 2019 crossed the previous record of $32.8 million, and will likely cross that 2004 record when the full financials for 2019 are released. Even more astonishing is the return on equity, which hit 44.6% during the same period, the highest ever in the two decades for which data is publicly available.

And all of this has happened even as the bank continues to clean up its balance sheet. Bad loans as a percentage of the total lending book are now down to just 4.7%, though much of that decline is due to an increase in the size of the lending book and not necessarily a volumetric reduction in bad loans.

Where to from here?

The key lesson from Citi’s experience in Pakistan seems to be to stick to one’s core business and not try to pursue business lines that may seem lucrative but may be more difficult to manage. While Citibank Pakistan’s management did not offer meaningful guidance on any potential changes to their strategy over the coming years, one suspects that the management feels relatively comfortable with their strategy thus far.

As the government begins to contemplate more privatisation transactions, the bank may once again find itself in a position to help serve as the government of Pakistan’s investment banker and lead many of those transactions. And as its clients continue to grow their businesses in Pakistan, its corporate lending portfolio is likely to continue growing at the expense of its government lending.

One thing remains certain, however: unless one of its bigger American rivals (and realistically, that really just means JPMorgan) decides to jump into the fray in Pakistan, Citi will retain an outsize influence in the Pakistani financial system that goes well beyond its relatively miniscule local size.

The only real competitor of Citi was ABN AMRO as both had sophisticated systems and processes that were built around the global model. Deutche, HSBC etc also had that, but their operation size was a lot smaller to pose any threat. Standard chartered, although having a large presence in Pakistan, was operating more like a local bank and the processes/people were a lot more localized, especially after Union Bank merger.

So with demise of ABN AMRO at the end of 2010, Citi benefited a lot with the departure of their main competitor as far as banking with MNCs and getting dollar denominated trade and investment deals is concerned.

[…] prefaced my comment with this acknowledgement of facts, I want to draw your attention to his recent article titled, “Citibank Pakistan scaled back, and became bigger than […]

Is there is any chance for consumer business resume in Pakistan by the citibank???

Comments are closed.