If you are a Pakistani professional who has not yet experienced not getting paid on time, consider yourself among the very lucky ones. Ask anyone outside the government, the banks, a few multinational corporations, and a handful of sophisticated local companies, though, and you get the same tales: salaries generally do not get paid on time, and some unfortunate cases, for months on end.

What is worse than not getting paid is the insolent attitude of many payroll departments and company owners. Both the human resources department and even employers or managers start saying asinine things like “why are you making this about money?” and “don’t worry, it’ll come when it comes”.

These are the kind of things that should and do make your blood boil.

But why does this keep happening, though? Why is so much of the Pakistani economy permanently late in paying everyone, not just employees, but also vendors, suppliers, and subcontractors? The answer lies in the banking system, specifically in the regulations that concern the risk management policies of banks, designed by the State Bank of Pakistan to keep the banks from being stupid with depositors’ money.

In this story, we dive deep into why these regulations exist and – more importantly – how they impact the lives of ordinary people and the economy.

How do the regulations affect business?

“The State Bank of Pakistan has said to us all ‘thou shalt lend to bricks and mortar,’” said Saeed Iqbal, the head of investment banking at United Bank (UBL), in an interview with The Express Tribune in 2012.

Iqbal estimates that the State Bank’s Prudential Regulations – which govern how much and to whom the banks in Pakistan can lend – effectively preclude close to 62% of the Pakistani economy, owing to the restrictive nature of what they allow as loans, what they require as collateral, the requirements relating to personal guarantees of business owners, and how much can be lent to each type of business.

But first, let us dive into why these regulations matter at all. Why, for instance, does a profitable business even need financing? If my company is earning revenue by selling its products or services, why am I not getting paid on time? The answer, of course, lies in the difference between what constitutes revenue and profits, and what constitutes cash flow.

There is an old saying in business: “revenue is vanity, profits are sanity, and cash is reality.” It is possible for a business to be booking strong revenues and profits, but have negative cash flow, simply by virtue of when its customers decide to make payments to it, versus when it has to pay its own vendors and suppliers.

Consider, for instance, the case of an advertising agency. Let us suppose that this advertising agency gets the contract to develop advertisements for Unilever Pakistan, and Unilever signs a contract on January 1 for a three-month engagement to develop ads, and the advertising agency begins work immediately. Let us suppose Unilever agrees to pay this advertising agency Rs10 million for this project.

Assuming no delays in the work, the agency finishes its work on March 31 of the year in which they signed the contract and receive an acknowledgement from Unilever that they have fulfilled the terms of their contract. At that point, the agency can book the full Rs10 million as their revenue.

Now, of course, the agency has its own expenses, including salaries for its employees, rent it owes on office space, utility bills, and any materials it needed to purchase to develop those ads. All of those are expenses it owes, and should have been paying for the past three months. For simplicity in this example, let us assume their expenses for these three months come out to Rs6 million, meaning the agency would make a Rs4 million pre-tax profit from its contract with Unilever.

However, despite that Rs4 million in accounting profit, the advertising agency has no cash yet, even though it has had expenses worth Rs2 million in each of the past three months. Even if Unilever decides to pay immediately on March 31 (which it never would), where would the agency come up with Rs2 million every month for the past three months?

The company’s founders only have so much money to start their business. Ultimately, the company needs financing, which a bank should be able to provide.

Now, suppose you are a banker who knows this advertising agency, and you know they have a contract that Unilever has acknowledged it needs to pay for Rs10 million. You should be willing to finance the entire Rs6 million in expenses for this advertising agency, knowing that even if they have to pay a high interest rate, they would still be profitable for the contract.

Essentially, the interest you charge on the loan would be your fee for lending them liquidity when they need it against expected future cash flows. In this particular example, the banker could even set a very high interest rate – let us say, 20% per annum – and it would still be worth it for the advertising agency to borrow the amount.

After all, even if Unilever took six months from the end of the contract to pay the agency, the loan would still only be outstanding for nine months, meaning that the company would only owe the bank Rs900,000 on the loan. Even after taking into account that additional interest cost, the agency would still make a profit of Rs3.1 million. And the bank would walk away from the transaction with an additional Rs900,000 in income.

Of course, the agency would prefer to not have to pay that amount in interest, but it may not have a choice, because in reality, Unilever will not be its only client, and that three-month project will not be its only project. It will have several clients asking it to take on multiple projects at any given moment in time, and if it wants to win that business, it cannot say: “sure, but we will start once our previous clients pay us so that we can use that cash to pay all the bills for this project.” Its clients would not do business with it.

That interest cost, then, is not something that can realistically be avoided. It is a cost of doing business.

So what happens if the bank decides: we will not lend to you. What if all your old clients still have not paid you yet, and you have Rs2 million in salaries, rent, utilities, and supplies you need to pay for this month? What would you do?

You would do what the vast majority of Pakistani businesses do: they would tell their employees that their salaries will be late. They would not pay the utility bills on time and hope that the power does not get cut off before they can pay for it (or they would outright steal the electricity). They might pay for some supplies in cash, and try to get the rest on credit.

At the end of this, eventually, when the agency gets paid, it will be able to pay its employers, suppliers, and bills, and will not have the interest cost to pay the bank. So, everything worked out for the better, right?

Not quite.

Because in that three months, one would have extremely frustrated employees, and because cash would be so tight, the company would not have the ability to aggressively go after new business, knowing that they would not have the cash to fund their operations to serve that new business even if they won it. So, yes, the profits from each individual project might be higher (because employees do not charge interest on late salaries), but morale would be low, and growth would be much lower.

In other words, for most businesses, it would be worth it to pay the interest on the loan and grow the business while retaining employee morale. And many businesses would borrow the money if the bank were willing to lend to them. Indeed, the bank would probably even be willing to lend to this company in this situation, were it not for the Prudential Regulations, which severely constrict what they can do.

Yes, we are aware that some seth businesses do not want to grow because the owners are happy with their lifestyle, and yes, we are aware that a substantial portion of businesses want to grow, but do not borrow because of religious beliefs of the owners, but we still believe that many other businesses would borrow from banks if they were allowed, were it not for the onerous regulations.

So, what are the Prudential Regulations?

These regulations exist in every economy, and every central bank wants to ensure that the financial system does not endanger the safety of the depositors’ cash, nor does a systemic collapse of financial institutions threaten the wider economy. What makes the regulations in Pakistan different from those in developed economies is the extent to which they specify what banks can and cannot do.

Specifically, no bank in Pakistan needs to develop a detailed set of risk-management policies, because the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) has already developed them for the banking sector: everything from counterparty limits, to loan size limits, personal guarantee requirements, relationship of the loan size to the bank’s equity and total lending portfolio.

Sure, there are some minor details that each bank needs to flesh out on their own, but the basic contours of every bank’s risk management policy is developed straight out of the regulations themselves, a situation that even the SBP itself does not find tenable, nor productive for the economy.

“We need to have a serious revision of the Prudential Regulations. Why should I, the central bank, do the risk management for the banks?” said Yaseen Anwar, the former governor of the State Bank, in a media interview several years ago.

What exactly are these risk management practices that the State Bank is enforcing on the banks? There are many and varied by borrower type, but for most businesses in Pakistan, there are two very important ones that affect their ability to borrow: the first is the requirement that most lending be secured (with severe restrictions on unsecured lending), and the second is that all small business loans be backed by a personal guarantee of the owner.

Each of these two rules sounds reasonable enough, and they certainly achieve their goal of protecting depositors. But the purpose of a bank is to be more than just an entity that protects depositors. It should also be looking for ways to profitably lend to the kind of small businesses that make up the bulk of employment in most economies, including Pakistan.

Let us take the first – and most serious impediment – of these two regulations: that of providing a security. Simply put, it means the bank is lending you money not against your ability to pay in the future, but against an asset that you own right now. For a manufacturing company, they could borrow against the land on which their factory is built, or against the value of the physical assets they own and so banks would be more than happy to lend to them.

But what about that advertising agency? What about a shopkeeper? What about a wholesale trader? Most of these types of businesses operate on rented premises, with very by way little assets that they own outright. Their cash flows – and therefore their financing needs – are far larger than the assets they might need to generate cash flows.

These businesses – known as “asset-light” businesses – tend to, on average, be more profitable than businesses that require a large amount of assets. After all, even if you have very thin margins, but require few assets to produce them, it is much easier to produce a high return on equity than a business that may have higher margins, but also high asset requirements.

But the State Bank’s regulations effectively mean that these businesses cannot borrow any meaningful amounts of money. Indeed, most services businesses in Pakistan would not be able to meet the requirements of providing assets as collateral against the money they want to borrow. And private-sector services businesses constitute nearly 53% of the economy, according to data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS).

This one single rule makes it difficult, if not impossible, for over half the economy to borrow the amount of money they need to run their businesses. No wonder nobody pays anyone on time in Pakistan. If half the businesses cannot raise what they need to make payments, everyone will always be running behind on making their own payments to employees, vendors, suppliers, etc.

Even if bankers want to lend to such businesses (and there is evidence to suggest that they may not), the State Bank does not trust the banks to make these decisions. It has decided to adopt the attitude of “we know best” and made the decisions on behalf of the entire banking sector, perhaps because it thinks bankers simply do not have what it takes to make the right judgements on these matters.

The second, slightly less onerous, but nonetheless cumbersome, regulation is that surrounding personal guarantees for any business classified as a small or medium-sized business. The State Bank defines a small business as one that has 50 or fewer employees, and annual revenue of Rs150 million or less. It defines a medium-sized business as one that has between 51 and 250 employees, and annual revenue of between Rs150 million and Rs800 million.

Most banks and financial institutions – even in larger, more sophisticated economies – require some form of personal guarantee at least initially. I am currently starting a business headquartered in the United States and both JPMorgan Chase and American Express required me to personally guarantee my business’ credit lines.

But over time, as my business builds a track record, I expect these personal guarantees to be dropped. In Pakistan, however, unless a business grows to becoming a large business (more than Rs800 million in revenue), it will always require personal guarantees from the owners.

This defeats the purpose of incorporating a company as an entity separate from the business owners. The whole point of limited-liability companies is to limit the liability of the owners in case the business suffers losses. Fewer businesses would be willing to borrow and grow if they had to take on the personal risk of losing their family house if they cannot repay their loans.

Of course, from a bank’s perspective, that is a good thing: business owners will be motivated to make sure they can pay the bank back. But more often than not, this simply means that businesses do not borrow at all, and the economy grows slower as a result.

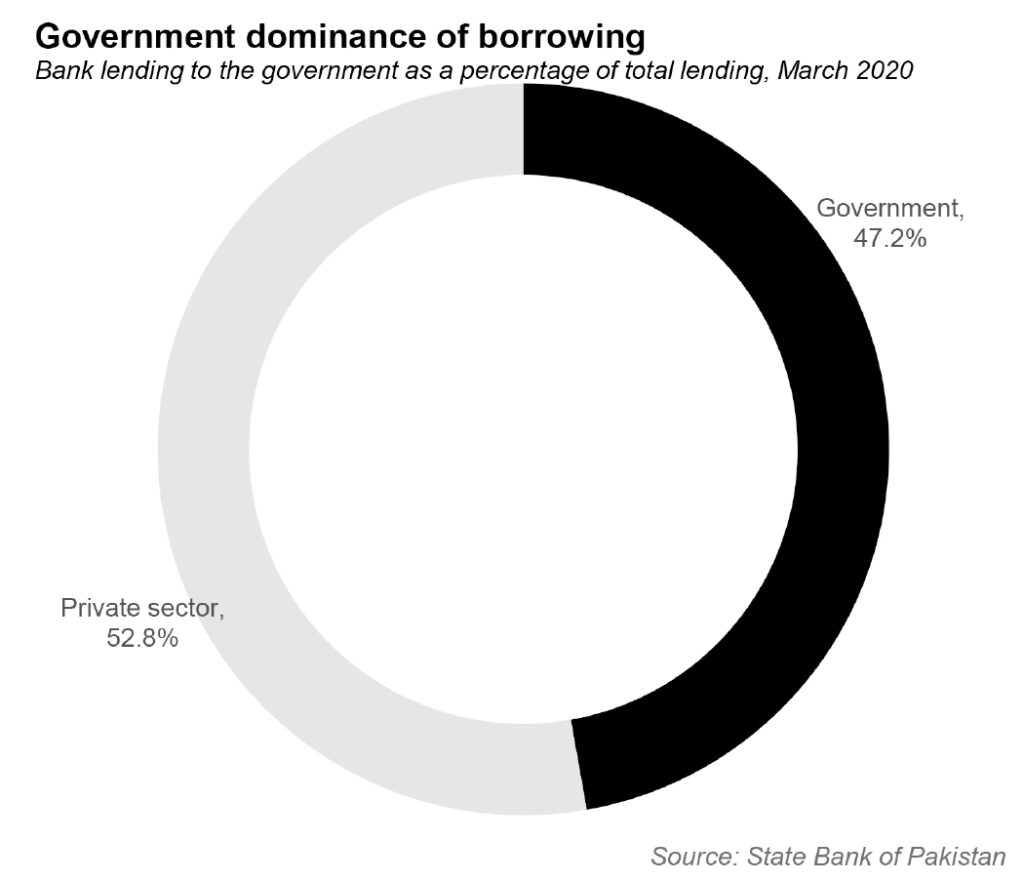

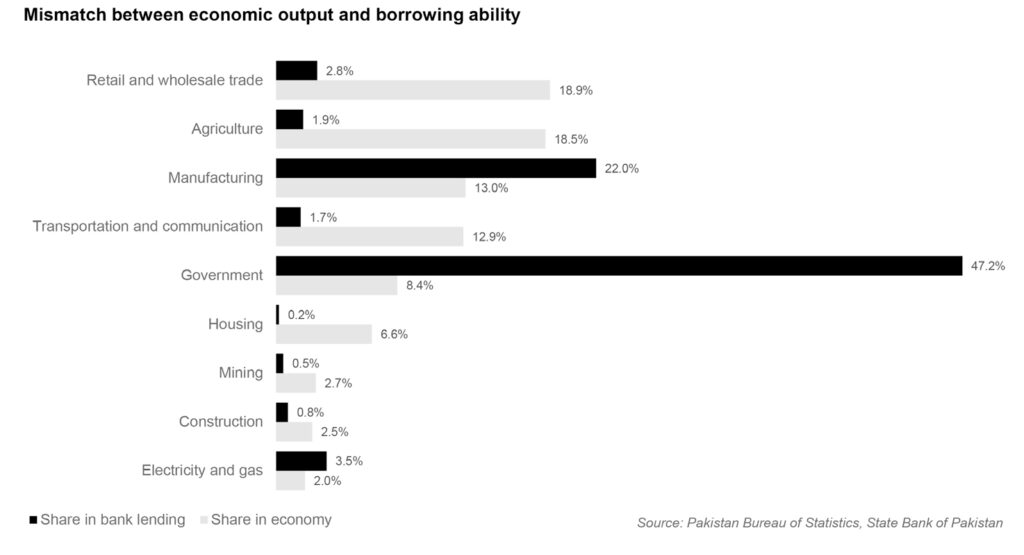

As a result, access to capital is highly distorted in Pakistan. Manufacturing constitutes only 13.0% of the economy but it got 22.0% of all bank lending (loans and bonds) as of March 2020, according to data from the SBP. Meanwhile, retailers and wholesale traders account for 18.9% of the economy but just 2.8% of total lending. Transportation and communication account for 12.9% of the economy but just 1.7% of total lending.

The financial services sector, in other words, is serving only a small sliver of the economy. And that, of course, has major implications for which businesses will have the ability to continue growing, and which ones will struggle to get by.

Change is coming, but slowly

Over the past few years, the State Bank has realised that the situation is untenable and the regulations need to be changed. It has over the past few years, for instance, changed the limit for “clean” lending – meaning loans that do not require collateral – from Rs2 million to Rs5 million. And it has introduced language in the Small and Medium Enterprises section of the Prudential Regulations that allows for lending on the basis of estimated cash flows.

However, the problem with that latter change is that even though the language says that banks can lend on the basis of future cash flows, it still requires them to lend against a security of some kind, which usually means some sort of collateral. For larger companies, banks may be willing to securitise the future cash flows and call them a “hypothetication of expected cash flows”, against which they lend, but the capital requirements against such lending still make it onerous on the banks, which is why they are not willing to do it as frequently, and certainly not for their smaller clients.

For the banking sector to truly be freed up, the State Bank will have to make unsecured lending much easier for banks, both in terms of removing the actual requirement for security, and by removing the capital requirements for unsecured lending.

In other words, the State Bank needs to start trusting the banks to actually do their jobs.

Will they fail initially and cause tons of losses? Of course, they will. But how else will banks develop the ability to lend to the economy unless they are first given the freedom to try and fail before ultimately succeeding? It is a bit like a parent wanting a child to learn to walk but also wanting that child to never fall down. The two go together.

The banks are not innocent either

For their part, the banks will need to get used to the idea that not all of their lending needs to be to the government, which has been the case for most of the past decade. They will need to invest in the human resources and technology infrastructure to be able to market and gain business with small businesses not just for their deposits but also their lending business.

Too many years of easy money have resulted in the banks letting those lending muscles atrophy. And until they reinvest in those, even regulatory shifts will not have much of an impact.

Your article misses many important points, either deliberately or lack of knowledge. First of all, these Prudential regulations (PRs) and other instructions and letters issued by SBP from time to time is a major revenue earner for SBP as every year they make heavy income from imposing penalties on all banks over violation of these risk management policies stipulated in PRs.

Banks treat guys from SBP as gods and their every word, even from a small manager level person in SBP with less than 3 years experience, is worth in gold and presidents and senior level management of banks even fire their top level employees if that SBP kid raise an objection. SBP’s fear among banks is so much that they don’t even challenge the penalty amount and pay whatever they ask. Everyone in the bank just does their own risk management (saving their ass) as even President knows that SBP may even fire him so they have no concern about doing the right thing and just follow whatever their gods (SBP guys) say. This same attitude is witnessed at all management levels of all banks in Pakistan. So forget about any change in banking practice as long as SBP is strictly monitoring these PRs. Onus is on SBP to change its policies.

Secondly you forgot a major point that majority of companies in Pakistan do not opt for loans from banks and by choice continue to remain debt free without asking banks to provide services. We are an unbanked economy mainly because of unwillingness to lend from banks, either due to fear of taxes as real income gets exposed, laziness or due to religious beliefs. So the fact that they delay their salaries payment is more to do with their own choice than any issue from banks or SBP.

Thirdly and most importantly, delaying salary payments to employees results in substantial savings for every company every month. Time value of money! It is financially beneficial for employers, especially those facing business crunch situation, to delay salary payment even for a single day. So the issue is also about willingness than capability. Employers are enjoying this norm as it is beneficial to them at the expense of workers.

It’s not just about delaying salary payment, have you ever tried giving loan to your friend, acquaintance, relative or anyone? Does that person pay back to you on time? Personally at least this never happened whenever I gave any loan as there’s always delays and reminders that need to be sent. It’s a general psyche in Pakistan to find excuses when you owe someone and unfortunately very few honor the commitment within the time. There are many employers with this mindset.

Changing banking rules would not result in sudden change in habits of employers to delay the salaries. The link you made between the two is very remote and ludicrous to say the least.

its true what you wrote.

Excellent response. Small and medium businesses, esp the ones highlighted by the author here like wholesalers, retailers and traders etc, deliberately want to operate outside the formal economy. It is not because of prudential regulations but their own thieving attitude that they stay away from banks. They’d rather keep bundles of cash under their shop seat than going to the bank to deposit this cash. Why? Because they want to avoid taxes.

Ask yourself the question, are there any strict regulations against DEPOSIT as well? No. Then why is majority of this 53% private sector staying away from banks. Because they want to stay below the radar.

Before linking prudential regulations, which btw have saved us from more than one financial meltdown, why not focus on improving judicial procedures in this country? Labour courts should be able to fix this problem of employees not getting paid. Instead of fixing the root cause (rotten judiciary is the root cause of every evil in this country but that’s another debate) the author chose to go with a sensational headline.

I’m glad the SBP works the way it does.

NO SALARY THIS TIME BY MCB EVEN ON 21st..

I have to PAY some charges, some sendings to LHR, pay fees of daughter, monthly to my joint family AND many more being living in Karachi but in vain.. what can I do now?

its true what you wrote.

Mostly when banks are accessed for loans they provide less amount than requested. The processes are cumbersome and rate of payments are very high. The process is also not confirmed. The bank loan approving committee can reject the application during the process. Documentation for loan and release of documents upon repayment are additional assignments.

Besides, running finance facility has played an important role.

Who on earth have so much time to read such lengthy articles???? Mr.Writer a suggestion to you is to keep your articles short, precise and to the point, dosen’t makes sense in writing such long and boring sum articles.

I think it is the mind set. Fortunate to work in a business where the payroll would be executed on the 27th of preceding month and every Thursday vendors shall be paid.

Above was the KPI Board would monitor on regular basis.

I’m took pm pakistan pm my friend im top friend my all took pm you my mother fory pay i.m wetang you money my mother house pay hand you thanks