The recent decision to ban non-halal dating apps has caused a stir on social media. On the face of it, banning these apps makes sense given the laws and moral codes of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. This, of course, only holds true if we assume that dating app users intended to defy the laws of Pakistan.

But there is an alternative explanation that users generally are interested in finding a partner for marriage for themselves. Then the question arises why would users use non-halal certified dating apps such as Tinder when halal alternatives are available?

Let us briefly consider the traditional context. Before the internet era “matchmakers” or “rishta aunties” were the main means of finding a compatible match for one’s children. The traditional mechanism ensured that the parents could chaperone any meetings if they occurred at all. This is not a uniquely South Asian Muslim tradition with other ethnic communities such as Orthodox Jews still using matchmakers today.

Matchmakers have not been behind the digital revolution and have also evolved to moving their services online. Take the example of the Orthodox Jewish website www.sawyouatsinai.com. In line with Orthodox traditions they facilitate matchmaking and similar to some cases in South Asia matchmakers can expect a voluntary monetary reward for their efforts. Matchmaking is such an important function of some societies that the streaming service Netflix even launched a show based on it called “Indian Matchmaking.”

The launch of a reality tv show based on matchmaking is not surprising given the economic importance of the wedding industry in India with some estimates being as high as 50 billion dollars annually.

But serious matchmaking orthodox Jewish websites that stick to religious guidelines and with added safeguards such as sawyouatsenai.com are a few in comparison with the ones that do not follow strict religious guidelines. That is true for other religions matrimonial/dating websites as well. For instance, Muzmatch the Muslim dating app that has an option for allowing a chaperone to check the conversation between two individuals.

Of course, the limit of chaperoning is as long as the conversation remains via the app and once adults leave the app for another platform no one can really chaperone them. In comparison with the Orthodox Jewish market the Muslim market for matrimonial apps does not have apps that are as rigid in following religious edicts as the app sawyouatsenai.com.

To be clear about one thing, the halal dating/matrimonial apps market business follows a for profit business model. The way matrimonial apps make money is to initially allow prospective Romeos and Juliets to use some basic features of the app. To actually send messages or see photos they have to upgrade their accounts and subscribe to their premium service. There are customer benefits to paying, one is that if someone pays for the app he or she is most likely serious about using it and unlikely to be a fake account. For the app provider it is their revenue in addition to any in app advertising they might allow.

Furthermore, the halal matrimonial app market is not solely catered to by companies that are religiously motivated. As mentioned about Muzmatch, you can choose to be halal or not. Likewise, not all the popular Muslim matrimonial apps are owned by Muslims. Consider Muslima.com, an app with over 1 million downloads according to Google play store. Muslima.com is owned by Cupid Media which is in the business of dating apps. Their motive is purely profit and they do not have any greater ideological calling for being in the halal dating app market.

So then what constitutes a halal app? Theoretically, it would be an app that adheres to the tenants of the matrimonial process in Islam. However, the market seems to define it differently. A visit to the google app store will show that Muslim or halal dating apps seem to be finding people with similar religious, economic, and other interests. In addition, that also does not mean the process of using the app is certifiably halal.

For instance, match makers are unavailable and nor are the chats moderated by app providers. Then it leads one to wonder if the Muslim dating apps are not always certifiably halal then why is Tinder banned in Pakistan for not being halal?

Tinder, according to The Guardian, was downloaded 440,000 times in the past 13 months in Pakistan. Despite this impressive figure it is not in the top 25 paid apps list of Pakistan which all are video games. The Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) have in the past banned gaming apps that were highly addictive or perceived to have immoral content such as PUBG and BINGO. One can understand and even advocate the banning of some games such as those that follow the “freemium” model.

Freemium games initial versions are free and to progress in the game players have to make in-game purchases of items that help them achieve their objective. Most players do not make such purchases but a small percentage do and they are referred to as “whales”. These whales are normally addicted to the game and the companies take full advantage of this addiction. Regulation in such cases by PTA can be fully understood, but matrimonial apps as per se are not addictive, then remains the question of remaining halal. But is banning applications like Tinder a solution to encouraging the use of halal apps? Especially when other halal apps are “optionally” halal?

There is the odd chance that there is some obscure strictly halal app out there but my review of apps uncovered no major players in the apps market. Plus, for any app to be successful it needs a certain critical mass of users. Or in other words network effects or network externalities meaning the greater the number of users of a matrimonial app the more valuable it is to its users. The advantage of dominant players such as Tinder in terms of network externalities is clear. Limiting the users’ choice of potential life partners is not in the interest of users.

Moreover, given that Islam is the dominant religion and roughly 50% of the population of Pakistan is males they have the right to marry people of the book or Christianity and Judaism in addition to fellow Muslims. Then is it fair to ban apps through which they could meet potential life partners? Moreover, for the non-Muslim population of Pakistan is it not unfair that their potential suitor pool is being unfairly curbed?

Online matrimony is a thing to stay and the trend is growing globally. According to PEW research about half of the US population has used an online dating site or application. This figure increases to 65% for unmarried Millennials. Moreover, about 12% of American marriages currently take place between people who met online. Furthermore, the PEW data shows that women receive more messages than men do.

In the context of a country like Pakistan, where women generally are not given much choice as men in searching for prospects for marriage, online matrimony might provide much needed respite. The western dating app Bumble, which is a major competitor of Tinder, has taken a step that allows women to avoid online harassment by only allowing women to initiate the conversation with men and not vice versa.

PEW research also sheds light on the dark side of dating apps. A few key issues are mentioned, namely, lying, fake profiles set up for scamming victims, harassment and data privacy concerns. Harassment includes stalking, name-calling, being sent inappropriate images and the threat of physical violence. To deal with the dark side of matrimonial/dating apps there exists the FIA cybercrimes wing. But the PTA could also step in and closely work with app owners to control such incidents. Such incidents are not limited to non-halal dating apps but also have been documented by the Metro newspaper in the UK for halal matrimonial apps.

In order to highlight some of the issues of users of matrimonial/dating apps have I conducted a sentiment analysis of user reviews of four such apps in the google play store. I choose four websites namely, Tinder, Bumble, Muzmatch and Muslima. Tinder and Bumble are international leading dating websites where as Muzmatch and Muslima are catered specifically for the Muslim market.

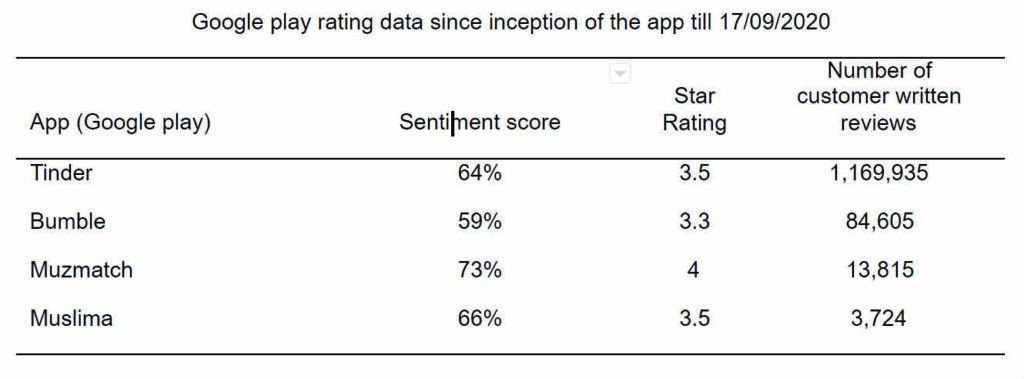

The sentiment score are the user comments quantified by coding the data into positive comments, negative comments, mixed comments and neutral comments. The higher the sentiment score the more positively rated is the app and it is represented as a percentage.

The star rating refers to the average number of stars the app has received with 5 being the highest possible score. The number of written customer reviews is the number of customers who left written comments and should not be confused with the number of customers who left a star rating. The table below presents the results of the analysis:

Muzmatch seems to slightly perform better than the competition, but one needs to keep in mind that the volume of reviews is far less than what Bumble and Tinder have as Muzmatch has a limited target audience. Whether their services would be preferred in comparison to the market leaders cannot be deduced from this data as Tinder and Bumble have many reviews from the non-halal app market.

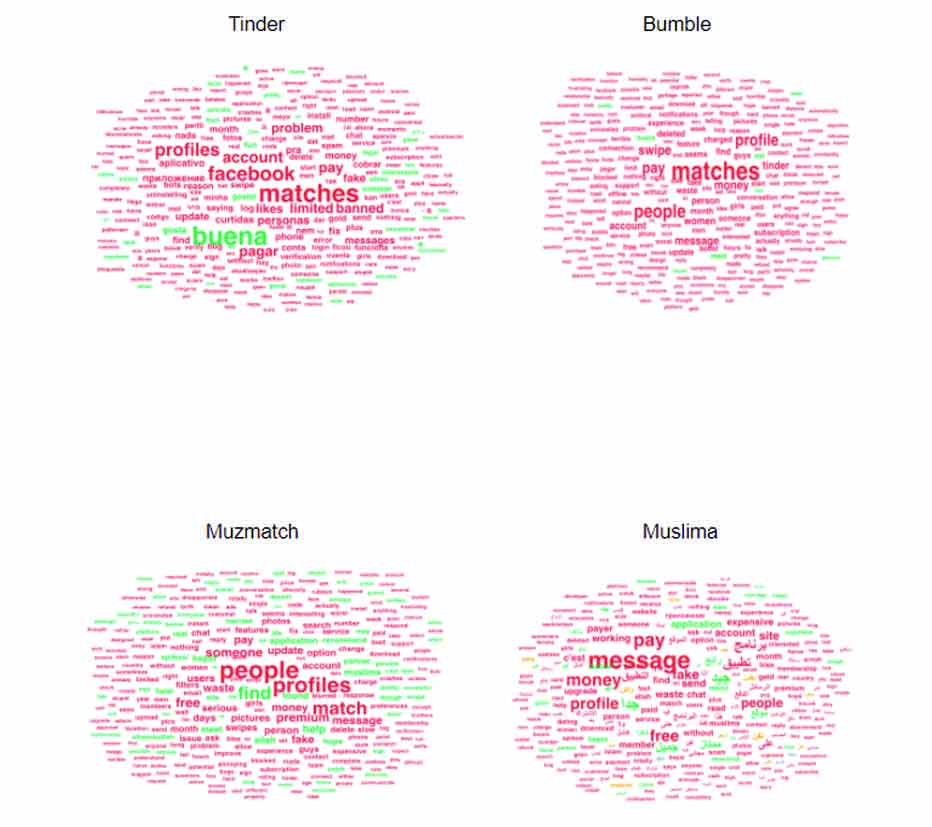

The second step of my analysis involves creating a word cloud. Unfortunately, the freeware software I was using had a limit of analyzing 10,000 words at a time and therefore I could not analyze all the reviews in the below word clouds. Words coloured green are positive sentiment words, words coloured red are negative sentiment words, words coloured yellow neutral sentiment words and words coloured grey are mixed sentiment words. The font size of the words show their relative importance. The word clouds are provided below:

The word clouds show that there is much that users are dissatisfied with matrimonial/dating apps. Some key words seem to be about fake profiles, money or subscription costs and other people using the apps.

This is where reform is needed especially given that people tend to be vulnerable when looking for a soul mate. According to some news reports Tinder is working with PTA to resolve some of their objections about “immoral” content, but PTA should be focusing on protecting consumer and user rights as well.

There have been many high profile incidents of peoples personal data being leaked and given the conservative nature of Pakistani society such data leaks can have a devastating impact on the victims life.

Overall, PTA needs to regulate apps. However, a myopic vision and only focusing on the grey area of morality of content is probably not the best strategy given that there are more pressing issues. Possible fraud, fake profiles, and stalking are potentially more serious issues that need to be addressed with matrimonial app providers. In addition, the Pakistan constitution enshrines the sanctity of marriage, so blocking matrimonial apps that may have dual purpose uses is probably not the best strategy, after all if that were the case other dual purpose products such as kitchen knives would have been banned long ago in Pakistan.

Online earning money for home.

There are a lot more important stuff than Tinder, PUBJay, TikTok – it should focus on bringing PayPal, eBay to the market.

Paypal, eBay will cool off the monopolistic markets like automotives, fintech, online shopping. Daraz is still but a big dent on eCommerce. The space is wide.

People use FB instead of Matrimonial sites. Who goes there. I never did

Banning any app doesn’t serve any purpose. If some app is ia not good enough, banning others to give it an edge makes the overall market inefficient.

There should be a level playing field and the competition will do the rest