There are a few things and products that Pakistanis take great pride in. Years of primary and secondary level social studies textbooks have convinced Pakistanis that the country’s production of sports goods and surgical equipment from Sialkot, mangoes, and textiles, put Pakistan on the world map and could be the answer to our export woes.

There is little analytical information in terms of developing and diversifying the economy by focusing on industry, modernising and focusing on technology. Pakistan seems more than content to be an agricultural economy. However, somehow or the other, Pakistan’s economy seems to be faltering even on this level in recent years.

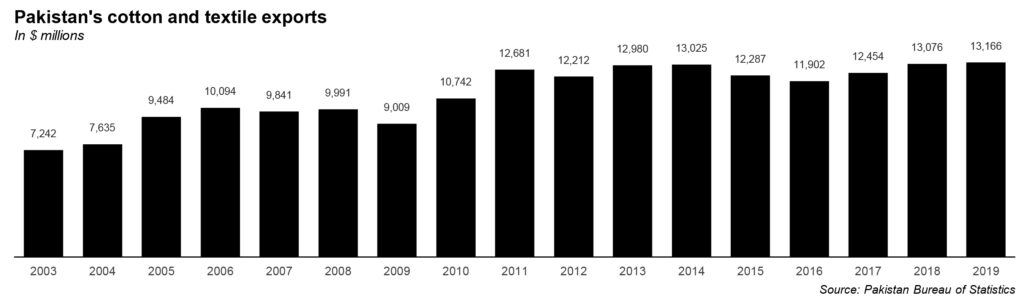

Ever since the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) government came into power in 2018, one of main objectives of their government has been promoting exports and discouraging imports to help the country’s massive balance of payments issue. Pakistan’s biggest exports, of course, are textile, and ginned cotton and cotton yarn is one of the most developed sectors within the textile industry.

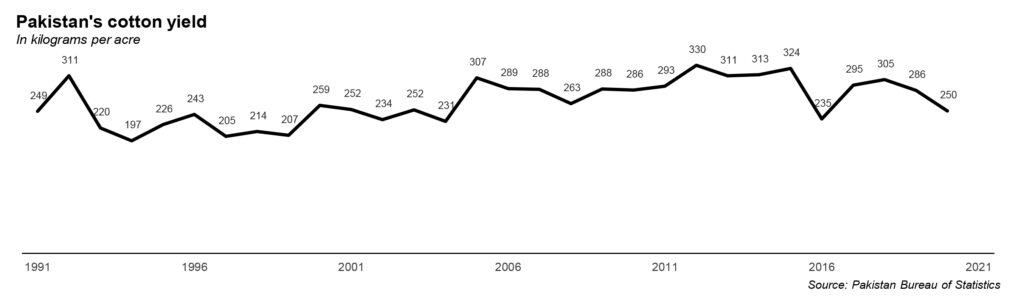

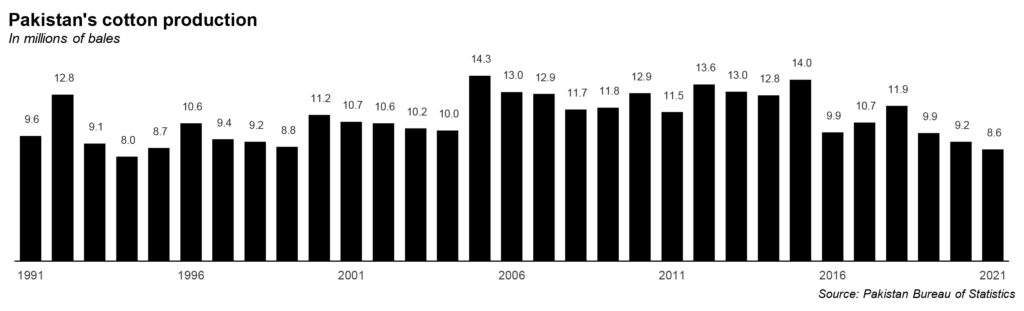

Pakistan depends on its cotton and textile exports, and this year, we are failing to meet our goals for how much we want produced. Here is the sobering statistic that has the entire industry worried: between 2015 and 2020, Pakistan’s production of cotton declined by nearly 35%, from nearly 14 million bales in 2015 to just over 9 million bales in 2020. The government keeps setting ambitious ‘targets’ but never meets them because it does nearly nothing to actually help farmers achieve those Soviet-style macroeconomic goals.

However, a final scramble to try and hit the numbers is underway. The only question is, will the country be successful?

Export goals

Currently, there is not really an issue of Pakistan’s cotton production or exports falling, the problem is of failing to meet targets. The recently approved long term textile policy 2020-25 has laid down a clear vision for how much Pakistan hopes to be exporting by the end of this decade. Under the plan, textile exports should be up to $25.3 billion by the end of 2025, and depending on the success of these five years, at $50 billion by the end of 2030.

For this, the country needs to increase not just the amount of cotton it produces, but also the quality of the cotton crop. Currently, Pakistani cotton is considered second grade, and if the crop quality is improved there would be greater demand at a greater price which would be a big boost towards meeting export targets. More importantly, by improving the crop, the entire textile industry will benefit since the quality of all products will improve at the source.

Pakistan has been missing its export targets since last year. In 2019, the production target for cotton had been 15 million cotton bales, and only 10.2 million bales were produced. Bad weather at the end of the year meant that there were only 8 million bales at the end.

The reason behind this, again, is that the government places very little emphasis on how the cotton is grown. Factors like climate change, lack of proper research by local research institutes, and no cotton policy, and the loss of cotton production areas to other cash crops have all played a role in this, which is why it is so important to focus on techniques to grow more and better quality cotton.

This method has worked for other countries. Two decades ago, Pakistan’s cotton was in demand globally. However over those twenty years, countries like Bangladesh, Vietnam and Cambodia have all used better growing techniques to get ahead of Pakistan. In 2003, when Pakistan’s textile exports were $8.3 billion, Vietnam’s textile exports were $3.87 billion, Bangladesh’s were at $5.5 billion. Now Vietnam is at $36.68 billion and Bangladesh is at $40.96 billion, while Pakistan is struggling to hit $25.3 billion.

Syed Fakhar Imam, the Federal Minister for National Food Security and Research, told a meeting of the Cotton Crop Assessment Committee on Friday in October this year that Pakistan will not be able to achieve the target set for cotton production once again. The situation is even worse since Pakistan was able to produce 10.2 million bales last year and lost 2 million to bad weather. This year, the government had set a modest target of producing 10.89 million bales, but only managed to produce 8.597 million bales.

The minister claims the main factors behind the low cotton production are: poor seed quality, lack of new seed technology, climate change, heat wave, cotton leaf curl virus, pink bollworm and white fly. The meeting also discussed how areas for growing cotton were facing problems, with Punjab suffering a decline of 4 percent in cotton production. Loss of cotton production has been observed in the Multan division of South Punjab. However, better crops have been observed in Bahawalpur and Dera Ghazi Khan districts.

“The estimated production in Punjab would be 5.3 million bales against a target of six million bales, 3 million bales against a target of 4.6 million bales in Sindh, while Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan both have 6,500 and 291,000 bales respectively,” Fakhar Imam told the meeting.

The reality

While the minister himself has admitted that production will be bad this year, sources close to the issues have told Profit that production will be even lower than what is being claimed. One source, wishing to remain anonymous, claimed that the maximum cotton production would be 5.5 million bales. “Pakistan will have to import cotton for the local textile industry worth $3 billion,” said the source.

According to the latest figures released by the Cotton Ginners’ Association of Pakistan, as many as 4.648 million cotton bales reached ginning factories across the country between November 16 and December 1, as compared to 7.448 million bales that reached the factories during the same period in 2019. A shortfall of 2.799 million cotton bales was recorded during the period under review, which was equivalent to a decrease of 37.59 percent.

In Punjab, 2.634 million bales had reached ginning factories as of December 1, which was 36.38pc less than last year’s 4.141 million bales. Similarly, during the period under review, as many as 2.014 million bales reached ginning factories of Sindh against 3.364 million bales last year, registering a decline of 39.10pc.

A total of 4.290 million knots of cotton reached factories across the country as of Dec 1, PCGA data showed. Out of 4.290 million cotton knots, the textile sector purchased 3.794 million, while exporters bought 0.045 million. It was further revealed that around 302 ginning factories remained operational in Punjab during the period under review, producing 2.418 million cotton knots, whereas 0.893 million cotton knots are still lying with ginners as unsold stock.

Given the history of bleak figures in the last few years and the current data released by the PCGA, the fear is that cotton crops will continue to lose ground to grow on as farmers choose to focus on more profitable crops. This means that Pakistan, which is supposed to be exporting cotton, might end up having to import cotton from other countries.

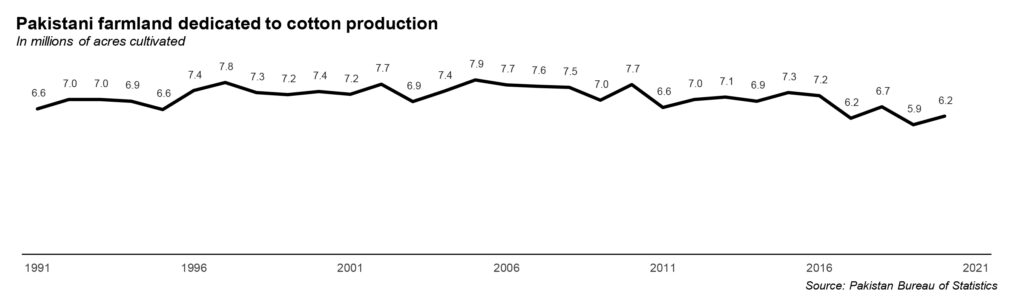

One member of the Cotton Crop Assessment Committee (CCAC), speaking to Profit, seconded this assessment, saying Pakistan is losing the cotton production areas which are necessary for the production of bales. He admits that the production is constantly declining as cotton growers are not getting a good amount of yield due to which they are switching to other crops which could maximise their revenues.

“The cotton research institutes of Pakistan are not doing their jobs properly. Pests are damaging the cotton crop badly as they become immune, and we don’t help much in killing them. This has disillusioned farmers from growing cotton,” they said. “Cotton crops require constant and state of the art research to deal with the threat of pests. Research is also important in deciding which fertilisers or seeds to use. This, unfortunately, is not being done properly at the moment.”

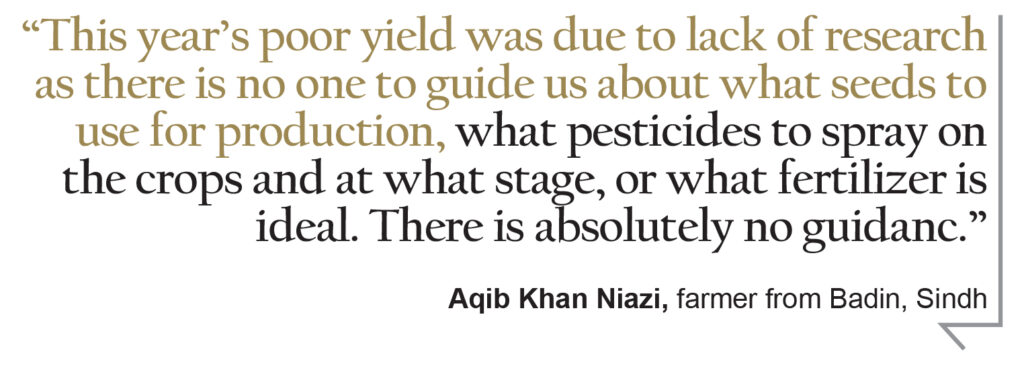

But there is little farmers can do about the pests until the research institutions, which are backed by the government, get their act together. “My yield from 300 acres (121.4 hectares) was reduced to only 100 kgs/acre which badly demoralised me which forced me to switch to Sugarcane this year,” says Aqib Khan Niazi, a progressive cotton farmer from Badin in Sindh.

“This year’s poor yield was due to lack of research as there is no one to guide us about what seeds to use for production, what pesticides to spray on the crops and at what stage, or what fertilizer is ideal. There is absolutely no guidance.”

Dr Ghulam Sarwar, a cotton botanist at the Cotton Research Institute in Faisalabad, on the other hand, defends the work he and his colleagues are doing at different cotton research institutes. “There are multiple reasons for the decline of the country’s cotton production including weather and growers switching to different other crops including sugarcane and maize,” he says. “We can’t force farmers to grow cotton instead of rice, wheat or any other crop.”

Meanwhile, acclaimed economist and Professor of Economics at Lahore’s University of Central Punjab (UCP), Dr Qais Aslam, says that cotton and its value added products contribute 10 percent of Pakistan GDP and 55 percent of export earnings, especially textiles. Cotton and textiles contribute significantly to employment levels in Pakistan both in agriculture and in large scale manufacturing sectors. But in the last few years, cotton crops have failed to deliver and Pakistan in 2020 imported cotton for its exportable textile sector. The issue of cotton crop failures are multiple:

“On the one hand it is a crop of warmer areas and as the climate changes the productivity of the crop falls. The attack of pests on cotton crops is multiple and not all farmers can bear the cost of pesticides that have become very expensive,” Dr Aslam adds. “The government has made no investment in agriculture in the last 30 years, or given any incentives to the farmers which has resulted in them starting to grow more lucrative crops because of the low profits on cotton.”

Cotton production area

This really is a problem. You can use all the modern techniques and do all the research you want, but as long as the area on which cotton is being grown continues to shrink, the amount of cotton being produced and in turn exported will continue to shrink. Confidential papers available with Profit have shown that the cotton production area and in turn yield has been constantly declining since 2011. Pakistan’s cotton production areas have decreased from 2.86 million hectares in 2011 to 2.48 million hectares in 2020. Cotton bales production has decreased from 11.13 million bales in 2011 to 8 million bales in 2020, against the target of 15 million bales set by the government itself for the current year.

Parliamentary Secretary for the Ministry of National Food Security and Research, the PTI’s Muhammad Ameer Sultan, says that this is due to humid weather, because of which pests attacked a large number of cotton bales, which is why the government failed to achieve the target of 15 million bales in 2019 and 10.89 million bales in 2020.

“The PTI govt is working on procurement of hybrid seeds to farmers and we are also planning to increase the price of cotton bales for the farmers. This would encourage them to move back to the production of cotton from other crops and increase the production area of cotton,” said Sultan.

Agreeing with Sultan, Malik Irfan Haider Budh, a progressive cotton farmer from Muzaffargarh in South Punjab who is optimistic, and says that cotton will regain its lost crown this year after the PTI government’s historic decision of coming up with support price for the first time in the history of Pakistan. “South Punjab is very happy about this development. Now, people of the area regard PTI as a farmer friendly party, and this has happened for the first time since the PPP. In the tenure of the PPP, farmers got prosperous and this time, PTI has tried to win the hearts of the farming masses.”.

But even he is grim when it comes to the recent cotton crisis in the country. He says that in recent decades, Pakistan has lost a substantial amount of cotton production for varied reasons. At the top of the list is the low pricing, which never helped farmers to recover their input expenses. Moreover, bugs and flies of new kinds have emerged that are pesticide resistant. “Climate change was another factor. Rains in April would delay wheat harvesting, which directly delayed the cultivation of the cotton crop. Now, when the climate factor remains there, the government of Imran Khan has tried to lessen the prices of fertilisers, he says.”

Malik Irfan maintains that a task force has been set up on pesticide in Punjab, which is working well on checking pesticides quality and prices. The PTI government has made a huge turnaround in the cotton sector because of which textile imports have gone up. Experts from the industry who are involved in cotton trade say that the government should work on the up-gradation of ginning technology, capacity building of farmers and introduce incentives for better quality cotton that would help in motivating the farmers.

During a meeting between Sindh’s Agriculture Minister, Muhammad Ismail Rahoo, and the All Pakistan Textile Mills Association (APTMA) on March 4, 2020. The agriculture minister assured the association of his complete support in increasing the per-acre yield of cotton in the country.

It was highlighted during this meeting that the introduction of modern farming techniques had become imperative for Pakistan to get a better yield of the cotton crop, because due to the deteriorating quality of cotton in the country, the millers had to import the commodity. Pakistan can save billions of dollars in foreign exchange if good quality cotton is produced.

Rahoo shared with the participants of the meeting that the Sindh government was seeking support from international experts so that it could train the local farmers, adding that the provincial government was also seeking help in introducing new farming technologies that could enhance cotton production.

The APTMA leadership requested the Sindh government to invest heavily in the research of cotton and develop good quality seeds on war footings. During this meeting, APTMA also agreed to pay the cotton cess per bale, provided the funds were utilised completely for research purposes by the cotton research institutes and also based on their performance.

Import of raw cotton and cotton yarn

But with the situation as it is, Pakistan will have to import cotton. This is despite the fact that there is a five percent regulatory duty on yarn import thanks to the long term textile policy 2020-2025 that actually established the production and export goals in the first place. However, textile importers have been expecting such a situation for a long time and have campaigned to have this duty removed.

“The decision to withdraw 5pc regulatory duty on the import of cotton yarn will greatly support the country’s textile sector, besides contributing to economic stability,” said Federation of Pakistan Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FPCCI) President Mian Anjum Nisar in a statement back in November. The FPCCI had earlier pointed out that the country would not be able to achieve its textile export potential due to limited access to raw material. It had suggested the government remove regulatory duty on cotton yarn so that exporters could be able to achieve price competitiveness and product diversification, the statement reads.

According to the FPCCI chief, local production of cotton was not sufficient to meet the demand of the textile industry, which was currently receiving huge orders. Cotton was not available at competitive prices due to the imposition of regulatory duty and hectic procedures, while Covid-19 outbreak and subsequent lockdowns had also worsened the situation, he informed in a press statement.

As per figures released by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), the country’s raw cotton imports clocked in at $196.097 million during July-January FY20 as compared to $137.870 million during the same period of last year, showing an increase of 42pc. The country imported 24,299 tonnes of cotton yarn during the first half of fiscal year 2019-20 from India, China, Turkey, Oman, Uzbekistan, Indonesia, Vietnam and other countries.

According to figures available with this scribe, Pakistan imported 14,100 tonnes of cotton yarn from China (58 percent of total imports), 2,067 tonnes from Turkey, 1,038 tonnes from Oman, 915 tonnes from Uzbekistan, 246 tonnes from Indonesia, 172 tonnes from Vietnam and 1,028 tonnes from other countries.

Pakistan also imported 4,733 tonnes of cotton yarn from India during July-September 2019 (19 percent of total imports in the first half of FY20). It is pertinent to mention that Pakistan had stopped importing cotton from India following the latter’s decision to revoke Article 370 of its constitution that granted Indian occupied Kashmir a special status.

This importing business may eventually grow and become central to Pakistan’s textile industry very soon. With the cotton growing continuing to decrease, fewer amounts of cotton bales reach ginners and spinning mills, which means the millers have to import cotton yarn to meet the demand of the local apparel industry as well as the export targets. So, we have to import cotton yarn to meet the demand of local and international clients, he adds.

The miller demanded that concrete steps should be taken to increase the production area, total production and per acre yield of the cotton. He advised capacity building and incentives for cotton farmers that might help in meeting the cotton bales target next year.

“The government should take some serious measures on war footings to address the issue of cotton production in the country in 2021, else it would be a decisive blow to the local spinning industry as they will not have enough cotton bales to make cotton yarn etc.”

Pakistan’s cotton imports are likely to touch $3-billion mark this year due to a lack of research on the commodity, which has resulted in reducing the overall cotton production area in the country. According to sources, Pakistan would have to import around 6.46 million bales this fiscal year which is likely to cost around $3 billion.

I hate paywalls.

And I’m sure journalists hate people not coughing up 500 rupees a month for all the hard work they put in.