Kaiser Bengali, the University of Karachi economist who has served as an economic advisor to two provincial governments, hates imported dog and cat food. Well, more specifically, he has used it as an example of how the country imports what he considers ‘luxury items’ even as the country struggles with grinding poverty. But what if importing those ‘luxuries’ was a way to help alleviate at least some of that poverty?

That appears to be what Procter & Gamble is on its way to doing in Pakistan, with an increasing localisation drive: investing in manufacturing locally – and for more affordable prices – what had previously been considered imported ‘luxuries’ by some economic observers, of whom Bengali is among the most prominent.

According to sources familiar with the matter, Procter & Gamble, the US-based giant that is the largest personal care goods company in the world, has decided to start local manufacturing of Pampers diapers in Pakistan in April 2021, Always sanitary pads in June 2021, and Safeguard liquid soap some time in 2022. This is in addition to the public announcement that its subsidiary Gillette will start manufacturing razors locally as well. Sources told Profit that the Gillette manufacturing is likely to begin in 2022 as well.

Our sources were not able to provide details on the size of the investment involved, though judging by the fact that the company will start production of three separate types of products, it is likely to be quite substantial.

Here is what makes the news significant, however: every single one of these imported products was once considered a luxury item for which there was a local – if inferior – alternative, and indeed, some people might well still consider them to be luxury imports. But Procter & Gamble is able to justify investing what is likely tens, if not hundreds, of millions of dollars in setting up manufacturing facilities that will employ hundreds of Pakistanis in the local manufacturing of these same items because it was able to gauge how big their market is because of imports.

In other words, it was imports that led to an increase in Pakistan’s manufacturing capacity, an increase in employment, and a significant increase in quality and a decrease in the price of goods that Dr Bengali may consider luxuries, but in fact are seen by those who use them as necessities that improve the quality of their lives.

So how and why is this happening? And does this mean that Pakistan should rethink its relationship with imports? In this story, we lay out the tale of Procter & Gamble in Pakistan, how and why it has slowly moved towards localisation of its imported products, how it is not alone in doing so, and what the implications of this might be for the government’s policies on trade and the obsession with the currency exchange rate and the current account deficit.

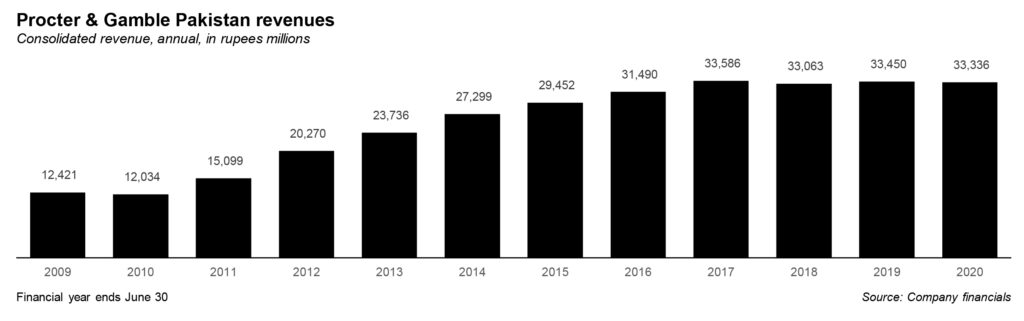

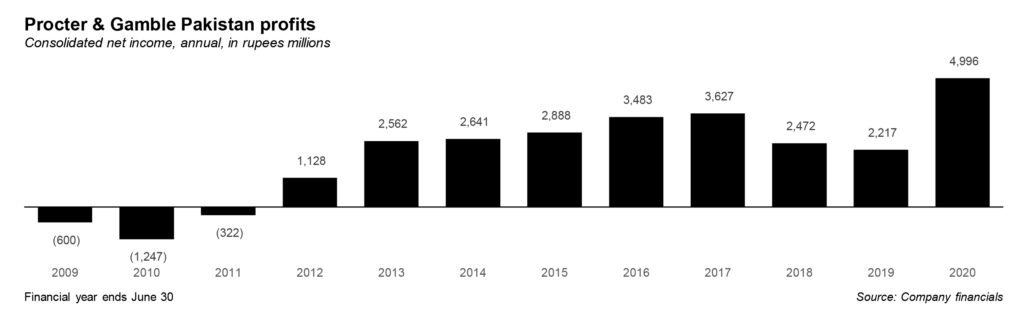

While Procter & Gamble representatives declined to comment for the story, Profit was able to obtain the company’s financial statements going back at least 11 years, which has allowed us to put together a picture of the company’s operations in Pakistan at a more granular level than ever before seen in a Pakistani publication. This story is, in part, the result of those findings.

Procter & Gamble in Pakistan

P&G is one of the largest consumer goods companies in the world and the owner of a set of brands that tend to be among the dominant ones in their respective market segments. It started life in 1837, when two Irish immigrants – William Procter and James Gamble – to Cincinnati, Ohio in the United States met each other through their wives: Olivia and Elizabeth Norris. Prior to meeting, Procter had been a candlemaker and Gamble had been a soap maker. Their father-in-law Alexander Norris persuaded them to become business partners, which is how Procter & Gamble was founded – as is still headquartered – in Cincinnati.

The company owns such iconic brands as Always, Ariel, Gillette, Head & Shoulders, Olay, Pampers, Pantene, and Vicks, in addition to many others. It owns 20 brands that each individually have sales exceeding $1 billion.

It started its existence in Pakistan on August 5, 1991, when it first imported a set of cleaning products into the country for the first time. Since then, for much of its history, Procter & Gamble remained largely a trading and branding presence in Pakistan.

Its Pakistan operations in its early years were mainly a corporate office that would help market its brands to a Pakistani audience, with a handful of employees who helped import the products from manufacturing facilities around the world, and then distribute them through large distribution companies in the country.

Over time, it has consolidated its operations and expanded them, setting up local manufacturing for a variety of products, including Ariel, which was the first product the company started manufacturing locally, and Safeguard. Over the first 25 years of the company’s presence in Pakistan, it invested $150 million into local manufacturing facilities to help localise its revenue streams.

In 2013, the company’s global parent announced a list of top 10 emerging markets on which it would focus over the next decade for investment, and Pakistan was on that list. In an interview with The Express Tribune, P&G Pakistan Country Manager Faisal Sabzwari said: “We have a very clear intention that we will continue to increase localised manufacturing in Pakistan.”

Among the factors he cited for the focus on Pakistan: urbanisation and a youth bulge. “If you compare the urbanisation rate in Pakistan with other developing countries, you will see that we are getting urbanised faster than others,” said Sabzwari back then. “Pakistan is one of the top countries adding 20-year-olds to the world, and these are the people establishing new families and helping market sizes grow,” he added.

In 2019, the company announced that it would invest $50 million in the local manufacturing of Pantene and Head & Shoulders brands of shampoo locally, through a 58-acre production facility located at Port Qasim.

At the time, Sami Ahmed, vice president at P&G Pakistan said, “We are committed to contributing our share in the economic development of the country. Our latest investment is testimony to our long-term commitment to Pakistan. For over 25 years, we have been serving consumers with high quality products and have made significant investments of over $150 million in fixed assets to date while nurturing and developing Pakistan’s finest talent and making them business leaders.”

Later in 2019, the company achieved another milestone: not only had it gone from ceasing its imports of Safeguard from other countries and started local manufacturing of the product, but it also began exporting Safeguard from Pakistan to 20 countries in Europe. For the financial year ending June 30, 2020, total exports of Procter & Gamble Pakistan products clocked in at Rs1,838 million ($11.6 million), the bulk of that being the exports of Safeguard.

That is correct, ladies and gentlemen: Pakistan did a complete 180-degree turn on Safeguard. It went from being an importer, to being a domestic manufacturer, and now to an exporter.

“This is an important milestone for our local operations. Our plant in Pakistan is one of the few locations in the P&G world where Safeguard is manufactured and exported from and it is the only site from which P&G is acquiring Safeguard for export to Europe,” said Sami Ahmed at the time. “Since the establishment of our soap manufacturing facility in Hub over 20 years ago, this facility has served Pakistani consumers with high quality products that has improved everyday life which has now become a lucrative export item as well.”

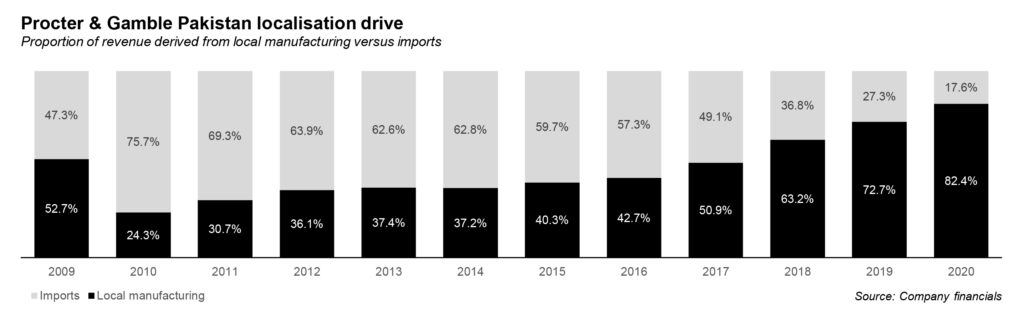

Over the past decade, Procter & Gamble has completely turned around its business strategy with respect to imports versus local manufacturing. In 2010, more than 75% of the company’s revenues came from imports and less than 25% from local manufacturing. By 2020, those numbers had been more than reversed: more than 82% of its revenues now come from local manufacturing and less than 18% from imports.

So how has this happened? What prompted Procter & Gamble to do this in Pakistan? The story starts with the economics of imports versus local manufacturing.

Local manufacturing is more profitable than imports, but because of imports

It really boils down to just this: gross margins – the proportion of a company’s sales a company retains after incurring the direct costs associated with producing the goods it sells – for local manufacturing are higher than they are for imported products.

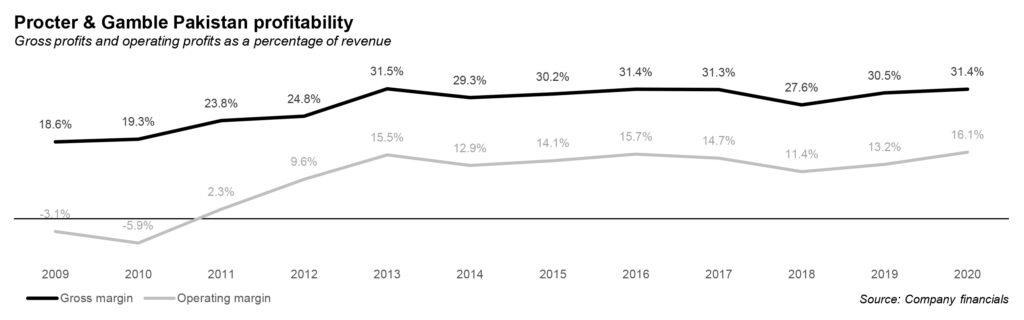

As the chart illustrates, for Procter & Gamble Pakistan, its gross margins on imported products have been lower for most of the past decade, and have been consistently lower for the past five years. And we are not talking about small differences in the margin either. In 2020, the gross margin on P&G’s locally manufactured products was 32.4% compared to just a 19.5% margin on its imported products.

That is a substantial difference, and it is therefore not surprising that P&G would consider increased local manufacturing: a boost to the gross margins is likely to fall straight to the bottom line as pre-tax profits, meaning every extra rupee in gross margins likely does not need to pay for any additional operating costs and hence will simply increase pre-tax income.

It is no coincidence, then, that the company’s gross and operating profit margins have increased as it has increased the share of local manufacturing. It is simply more profitable to do so.

But this is not a case of Procter & Gamble being late to the party and realising that it should have been manufacturing these products locally all along. No, this local manufacturing profitability is the direct result of the imports.

Here is how that works. Any student of economics knows, in order to be able to produce a product at a reasonable price, you need to have economies of scale. The more units you are able to manufacture, the lower the average cost of an individual unit. For some products, while Pakistan does provide reasonably priced raw materials and low labour costs, those savings would be dwarfed by the fact that the market for many products in Pakistan is tiny.

Procter & Gamble has two ways of dealing that situation. It could either build the large manufacturing facility that would have the capacity to produce a large enough capacity to achieve economies of scale, and then invest more still in the marketing, branding, and distribution of the product and hope that the market adopts its product. Needless to say, this is a high risk approach since it requires all the investment to be upfront.

The other approach involves P&G simply importing the same product from a market where it has already been launched and achieved economies of scale, and testing its market size by marketing and distributing it in Pakistan, doing studies on how much its sales might increase if the price went down, etc. This is significantly lower risk for the company, since it would have reasonably accurate estimates of its market size beforehand and would be able to plan its manufacturing capacity accordingly.

In short, it is the imports that help lower the risk for P&G, and thus allow it to invest more in Pakistan, having alleviated what is usually the single biggest reason it would get from its global headquarters to say no to an investment in Pakistan: “it’s too risky”. Imports allow P&G Pakistan executives to show their regional and global bosses that they have achieved sufficient product-market fit and scale in order to justify additional investment.

As a result of these so-called ‘luxury’ imports, Pakistani families will now have access to better, more affordable diapers, Pakistani women will have access to better, more affordable sanitary pads, and Pakistani men will have access to better, more affordable razors. Did we mention that the country gets an increased stock of foreign investment, increased employment opportunities for people in Pakistan, and potentially even future exports?

For the company itself, there are considerable advantages to greater local manufacturing, starting with the fact that its revenues would have less exposure to the volatility of the currency exchange rate. This has been a debilitating weakness for P&G’s business in recent years. The company’s Pakistan revenues have effectively been flat since fiscal year 2017, following which there have been three years of virtually no growth at all. Not coincidentally, those three years have also been marked by extreme volatility in the exchange rate of the Pakistani rupee against the US dollar, the currency of nearly all global trade.

Local manufacturing, therefore, is not simply a way to boost profits. It would also serve as a risk mitigant for companies like Procter & Gamble.

P&G is not alone in relying on imports

Of course, P&G is by no means alone in using imports as a way of reducing the risk of investing in local manufacturing. In 2011, Coca Cola started manufacturing cans to sell its iconic Coke cans in the Pakistani market. Prior to 2011, the company had been importing Coke cans from manufacturing facilities in other countries. Those imports helped establish a baseline for the company to determine its level of market demand, which it is now able to capture through domestic sales.

Indeed, one of Coca Cola’s can manufacturers in Pakistan – Pakistan Aluminum Beverage Cans Ltd – is a joint venture between the US chemicals and materials giant Ashmore and the local Liberty Group and has recently been valued at $100 million, according to a December 2019 report by Bloomberg. That subsidiary, which started off producing cans for Coca Cola in Pakistan now produces 1.2 billion cans a year and exports them to Afghanistan and Bangladesh as well.

And it is not even just legal imports that multinationals monitor. A Unilever official, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said that the company is aware of the illegal imports of its products that are then sold at high-end supermarkets in Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad. They keep track of which imports tend to have the most shelf space in order to study if they should start officially importing them into Pakistan as a prelude to domestic manufacturing.

So, it does not even have to be imports that the company engages in themselves: sometimes, smugglers start providing hints as to which products the market craves, and if the demand grows big enough, eventually, there will be local manufacturing of the product itself.

What does this mean for trade policy?

Needless to say, in a country where imports are seen as a necessary evil, the notion that imports can actually be good is somewhat of a controversial assertion, even though the most basic understanding of global trade states categorically that, in general, trade leaves both the exporting and importing country better off than had there been no trade at all.

In other words, imports are necessary, but not an evil to be tolerated, but in fact an essential part of the economic progress of a country.

Take, for instance, the import of sanitary pads and diapers. Between 2014 and 2017, the country imported over $100 million worth of both products every single year. But it is those imports that also persuaded Procter & Gamble to set up manufacturing of Always and Pampers. Those imports will eventually go down as more and more domestic manufacturing of reliable quality brands comes online.

So how do we reconcile the notion that imports can serve a useful purpose with the idea that grips Pakistani economic discourse that somehow, imports must be minimised, and the current account must always be in a surplus.

Reality, of course, is always more complicated than simple dicta would suggest. The current account is not an actual measure of any kind of economic progress. It is merely a leading indicator of what will happen to the currency exchange rate over the next few months. And the currency exchange rate, in turn, is not a reflection of economic strength either. Yes, a stable exchange rate is a nice-to-have, but not at the expense of foreign borrowing to make that happen.

Instead of obsessing over exports and disfavouring imports, perhaps the government could try simple openness as a regulatory strategy. Let people import whatever they want – with minimal barriers and low taxes – and export whatever they can.

Do we really think that what Procter & Gamble achieved with diapers and soaps is not something that could also be achieved with bigger things like cars? Imagine if the government allowed the imports of used cars without astronomical taxes, regardless of whether a car was a ‘luxury’ or not? How many people would start buying used Mercedes Benz vehicles? And what would Mercedes do if it saw a lot of used Mercedes cars being bought in Pakistan? How long before they would start manufacturing locally? And what would that then do to the local car market, and local employment in high-paying automobile manufacturing jobs?

We leave it to our readers to imagine answers to those questions, as well as think of others that could also be asked. But unfortunately, these are not questions that are typically thought of by policymakers in Islamabad, who seem to think of it as a personal insult if the exchange rate declines during their tenure in office.

Instead, we are left with governments pursuing two completely opposing goals at the same time: trying to increase imports, and trying to keep the exchange rate of the rupee artificially propped up. And what is worse is when we use borrowed money to do so.

But what hope is there for a government advised by economists who think of sanitary pads and diapers as luxuries for the elite rather than necessary goods that need to be made more affordable for all?

So what you’re saying is that a potential market is gauged by imports and that duties shouldn’t be imposed as this might impact future investment in Pakistan?

The priority on curbing imports was because Pakistan couldn’t afford them. With imports outstripping exports by a considerable margin there was a danger the dollar reserves would completely disappear. Without fixing the macro economic issues then the country was headed to default.

Once Pakistan is on a better footing with exports rising then imports will rise also but not out of control with the consumption lead growth encouraged by the previous government.

The fact that P&G are investing is Pakistan should be applauded. Maybe they are spending potentially 100s of millions of dollars is because they want to circumvent the duties being imposed on their products. Trump was doing the same in the USA by imposing duties on foreign imports to encourage localisation of production to grow the job market.

Have you considered that P&G may have other research to hand such as the young demographic of the population. The numbers in the growing middle classes. The growing number of people living in the city. To simply say it’s the amount they used to import dictated their investment is lazy journalism.

100% agreed. Imported soaps are like Rubbing dollars on body in washroom. Anything imported should be discouraged. It is due to good policy of current government thats why P&G is investing in Pakistan else diapers were imported and present at top shops for decades

It is imported product that could not compete with locally manufactured in pricing which has compelled them to go for local manufacturing.

Most corporations are facing a slump in demand and no credit goes to current government for what P and G has done. High price of dollars has caused more harm to our imports dependent country.

As soon as import dependent corporation close down or start local manufacturing the better will be for government of PAkistan and its people

Isn’t it all about the Gross Profit they are making?Profitability is huge on local manufacturing as compared to imports.

Importing and exporting should be neck to neck in order to avoid trade deficit.

The demand for the products were always there. Not only did multinationals import but they also took back their profits. This was double outflow of USD$ from the country which was causing a loss the country. Also these companies imported products at higher costs (because the exporter and importer are same parent company).

The reason they are coming into local manufacturing is because some Pakistani Entrepreneurs took the risk and set up local industries giving them a hard time. Many brand examples are available in Diaper Category.

The govt should continue to highly tax any product that has the potential to be made in Pakistan and therefore also can be exported.