By now, anyone who has been observing the Pakistani banking sector has had the same lament for the past 10 years: why do they not lend to the private sector? Why are they so content to lazily continue to plow their growing deposits into government bonds?

There are good reasons why the banks in Pakistan have seen superior risk-adjusted returns on government bonds compared to private sector lending, some of which has been covered by Profit in previous editions. This story, however, is not about why they find government lending attractive, but rather why they find private sector lending unattractive.

First, some context: since the second quarter of 2011, the government of Pakistan has accounted for a majority of the lending by banks in Pakistan, almost without interruption, according to aggregate banking sector data from the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP). It has also accounted for the majority of net new lending for that time as well.

And even when the banks do lend to the private sector, it tends to not end very well for the banks. The country’s infection ratio, or the gross non-performing loans to gross total loans, is not exactly great either. That figure stood at 9.7% in the first half of calendar year 2020, compared to 8.8% in 2019. Still, at least this is somewhat manageable: to recall, that ratio reached an all-time high of 16.7 % in September 2011, and a record low of 7.1% in June 2007.

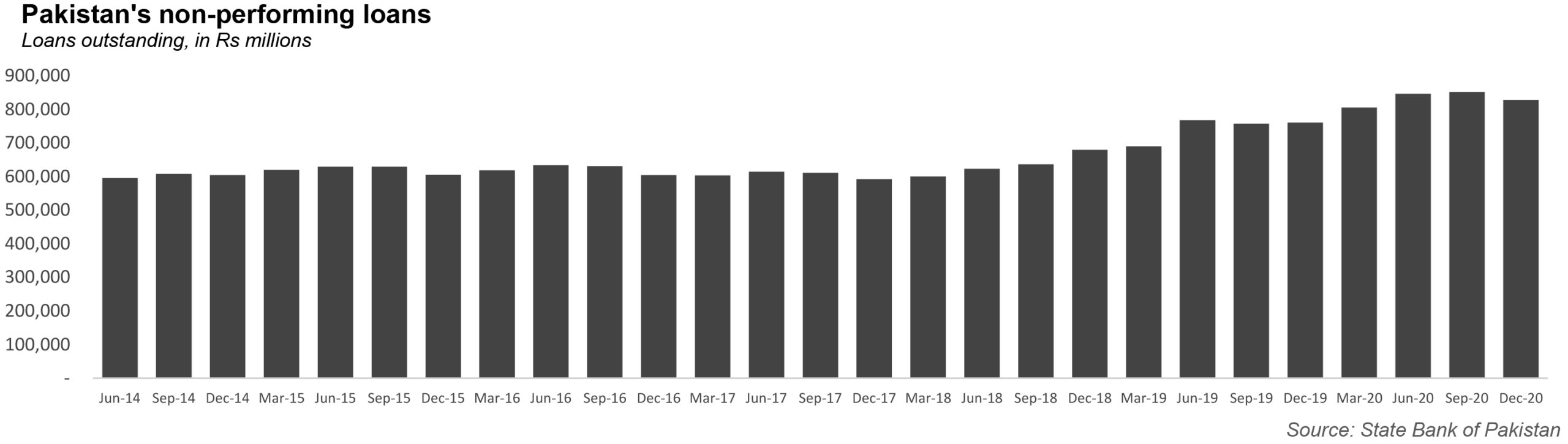

The current amount of gross non-performing loans for banks in the country, as of December 2020, comes in at a staggering Rs829 billion, according to State Bank data.

Let us place that number in context: In developed economies like the United States and Britain, this ratio is typically around 1% of total loans outstanding, or sometimes even less. In the United States, for instance, when the NPL ratio went from 1% in 2007 to 5% in 2009, it caused the greatest financial crisis the country had ever seen in almost a full century. Even in India, the worst the ratio had ever gone before the pandemic was 11%. In Indonesia, the ratio often hovers around just 3%.

In other words, Pakistan is unusually bad at private sector defaults, even by emerging markets standards. How did we get here? It is a question that banks are asking themselves as well.

At least part of the reason appears to be legal: both the law as it is currently written, as well as judicial precedents and practices as established by the courts. As behavioural economists are fond of noting, the more you incentivise something, the more of it you will get. And in Pakistan, the law, it seems, incentivises taking a loan from a bank and not paying it back.

Yes, we are talking about the standard problems of the Pakistani court systems, where when banks take legal recourse, typically against large companies who have defaulted, they find that their case is stuck in courts for years – sometimes even decades. But as we will note in this story, that is far from being the only problem (though it is, admittedly, one of the biggest ones).

And that is why Profit finds itself in the unusual seat of, for once, agreeing with the banks. Around the world, this very ability of banks to immediately receive their money, or for one’s assets to be captured by the bank, creates a system of checks and balances, and also, for banks to not exactly be viewed favourably. But in Pakistan, the lack of an efficient, or even ruthless judicial system, means banks are simply institutions one can take money from, while court cases are pending.

It does not help that there are several companies in Pakistan who are perfectly comfortable evading accountability when it comes to their loan defaults. Why is this happening? Profit takes a look at some of the reasons behind this quagmire, and the very real ramifications it can have.

Designing a bankruptcy law: competing pressures

When it comes to designing effective banking laws to prevent the rise of non-performing loans one has to consider this main point: how does a society enforce a loan contract against a borrower who has defaulted on their loan payment obligations, and what is the most effective way to go about it?

In designing such a law, there are two sets of interests that need to be considered: those of the borrower, and those of the lender. Make matters too easy for the lender, and you open up the possibility of the lender engaging in highly exploitative behaviour with the borrower, and with a reduction in the demand for loans over time. Go in the opposite direction, however, and lenders would not be willing to lend to otherwise qualified borrowers, reducing the optimal level of lending and economic activity in the country.

In Pakistan, the law and even more so, the legal system appears to be biased in favour of borrowers, forcing banks to go through the full court case before they could recover the property from the loan defaulter, a process that takes several years and costs millions of rupees for each individual loan.

As one source put it, the current legal framework has proven to be a shield for habitual defaulters, to manipulate the system and delay payment of money they owe for years.

Part of the problem is that key word: banking courts. Some context: The Pakistani Judicial system consists of district courts that cover civil and criminal matters, high courts in each province, and one Supreme Court in Islamabad. Separately, the system also includes specialized courts, such as banking courts, customs courts, drug courts, anti-terrorism courts, labour courts, etc. These courts are manned by district judges, and have more or less the same powers as a district court.

Banking courts are special courts constituted under Section 5 of The Financial Institutions (Recovery of Finances) Ordinance, 2001. In Pakistan at a provincial level, banking courts are working to deal with cases relating to recovery of finances with the aim of monitoring obligations of financial institutions and the borrowers.

The issue of delays was so pervasive, that in 2018, the Sindh Judicial Academy commissioned a report, “The Causes of Delay in Disposal of Cases in Banking Courts”. The report examined five banking courts in Karachi, covering 2,494 cases. A large chunk of commercial activity and banking litigation occurs in Karachi, which makes the report a good barometer for the state of affairs in the rest of the country.

The findings were not kind. First, one must understand that cases pending in general (and not just in specialized courts) is a huge problem. For instance, there were 118,687 pending cases in district courts in SIndh in 2016 alone. There are meant to be nine banking courts, but only five are functioning at a given time, and their backlog runs into thousands of cases.

The current legal system as it stands is overburdened and tardy. The report noticed for instance, that there seemed to be no consistency at all to the length of delays: “The variation in disposing of the cases was significant as some cases were decided on the day of the filing, while others took 23 years to decide.” According to the report, the hearing age took the most part of the litigation process, as on average, cases took 478 days to conclude hearing. Civil cases could take 464 days, while criminal cases would take 388 days.

What was happening? In banking cases, frequent adjournments by the advocates was one issue. Another issue was absenteeism: of the both parties of the accustomed persons in criminal cases, even of witnesses.

Then, banking courts suffer from vacancy, which is the period during which a court remains without a judge. This is due to one judge relinquishing his charge till the assumption of charge of the said court by another. In this intervening period, many cases that are put up to be heard have to suffer delays in their cases’ progress. All the cases fixed for hearing in the interim period are consequently adjourned, which adds to the delay, simply because judges are in limited supply, and vacancy can go on for months and years.

The report noted that presiding officers at banking courts often have little academic qualification to “comprehend the subtle nuances involved in banking litigation. These same unqualified presiding officers were mentioned in the report as having “been very liberal and generous in granting adjournments during various stages in the litigation process, even without an application being filed by parties to that end. This is a very harmful practice which has been identified as one of the major reasons for delay”.

The whole point of a specialized court is so that cases can be dealt with in a judicial environment designed to facilitate such matters, and to resolve it as efficiently as possible. That is not the case with banking courts in Pakistan, where cases essentially go to languish. This defeats the point of expedited recovery of finances.

The delays are severe enough to affect the entire banking industry. For instance, in April 2019, the Pakistan Banks’ Association (a powerful lobbying group that was established in 1953) wrote a letter to the Chief Justice of Pakistan. “Although the special statue [the 2001 Financial Institutions (Recovery of Finances) Ordinance – discussed in the next section] was promulgated to provide speedy disposal of recovery cases however these cases are confronted with serious crisis of inordinate delays and thereby causing substantial losses to the banking companies for sustained growth. As these advances are extended against public deposits, the banking companies can find it difficult to distribute fair profits among the public and maintain a healthy minimum capital adequacy ratio with the SBP.”

Regardless of the claim, the letter also said that delays go on till five to seven years, and gave a list of recommendations that they wanted implemented. First, they wanted only recovery cases to be placed before the special benches of the respective High Court of each province. The report claimed that, “as a matter of practise, the special benches are burdened with other cases of various nature and thus, recovery matters are not taken up due to paucity of time.”

The letter also said that they needed to fix the trial duration of a maximum of six months regardless of the amount in dispute at both high court and banking court levels. All miscellaneous applications filed during the trial should be decided expeditiously within a period of two weeks; and any party delaying the recording of evidence should be penalized.

Changing the foreclosure law

Of course, these are suggestions. But it was timely – and allowed for another law to be re-examined. Just a few months later in July 2019, Prime Minister Imran Khan introduced the Naya Pakistan Housing Programme, which has as its goal to build five million new housing units in Pakistan over the next five years.

The only problem was that the Asian Development Bank (ADB) was unwilling to give loans for this project without some kind of reassurance with regard to Pakistani law. After all, those five million homes need to be sold to people, and most of the buyers will need loans to buy those homes, which in turn means that banks need to be willing to lend to those new borrowers. Banks, however, would not be willing to lend without knowing that, if the borrower defaults, they will be able to recover the money by selling the house.

Surely, there must be some law designed to make life easier for banks? Actually, yes: the 2001 Financial Institutions (Recovery of Finances) Ordinance. The ordinance came into force in the early years of the Musharraf Administration, when then-Finance Minister Shaukat Aziz was seeking to update Pakistan’s regulatory structure to make credit markets in the country function better. It was intended to replace the 1997 Banking Companies (Recovery of Loans, Advances, Credits and Finances) Act.

The 2001 Ordinance was designed to make it easier for banks to take control of and sell property of loan defaulters without having to wait for a court order to do so. This would significantly reduce the banks’ risks, and thereby make it easier for them to lend to the private sector. The 2001 law has 29 sections, of which Section 15 allows banks to sell mortgaged property, in the case of a default in payment by the customer.

This section was in place until December 10, 2013, when the Supreme Court of Pakistan declared Section 15 of the 2001 Ordinance as ultra vires, or an act that is beyond one’s legal authority, to the constitution of Pakistan. Section 15, it was stated, did not have adequate protections for borrowers. The government then scrambled to amend the ordinance, and after approval from the legislature, The Financial Institutions (Recovery of Finances) Amendment Act was signed into law in August 2016.

The Lahore High Court suspended the ordinance almost immediately, before reversing that decision in 2020, spurred as it was somewhat forcibly by the prime minister’s office. The decision was not close: four of the five judges agreed with the defendants: the federal government, the State Bank, and the banking industry. The bench argued that the new Section 15 had adequate protections for borrowers: for instance, the borrower could object to the creation of the mortgage liability and amount of the outstanding loan claimed in a banking court. The borrower could also exercise the right of redemption of property, subject to the payment of the outstanding loan amount. Similarly, banking courts are given exclusive rights to judge disputes.

Yet despite the new ordinance, according to sources within the banking industry, it is still extremely difficult for the banks to determine borrower’s default and sale of mortgaged properties without the intervention of the courts. And even though the law exists, it remains practically ineffective because the courts grant long status quo orders against its implementation.

The implicit interest-rate subsidy in default

Here is where the case of perverse incentives baked into the law get even worse. The 2001 Financial Institutions (Recovery of Finances) Ordinance includes in Section 2, Subsection 3 a clause that effectively offers an active incentive for any borrower to default.

The clause says that if a borrower defaults, their obligation to the bank is the default amount plus only the bank’s cost of funds from the day the bank says they went into default. Note, that it does not say that the borrower owes the interest rate that they agreed upon in the loan agreement. It says that the borrower legally only owes the cost of funds.

Why does that matter? Because a bank’s cost of funds can be as low as 2-3%, whereas interest rates agreed to in the loan agreements tend to be north of 10% on average (usually 12% or even more are not unheard of). That implies a massive interest rate subsidy. So, if you take a loan, the next thing you do is go into default, invest the borrowed money into real-estate, bonds or stocks (depending upon your risk appetite), and lawyer up. Then, after ten years or more, settle the bank by paying the principal and the absurdly low interest (cost of funds) back to the bank, get your name completely cleared off the credit bureaus’ databases as a defaulter and remember to pat yourself on the back.

Frankly, given this provision in the law, it makes complete rational sense for a borrower to default almost immediately on every loan,: you get a very low interest rate, and you face almost no consequences of being shut out of the financial system (which a default in a normally functioning financial system would entail).

Culture problems

So, if you are a bad faith actor, and you have borrowed money from a bank, are you obligated to pay them back? Think about it: part of how crime is deterred is not by the severity of the punishment; it is that the punishment is actually enforced. So it does not matter how many times the Lahore High Court meets and figures out legalese. Either way, a company can sit secure in the knowledge that there will not be an enforced penalty.

This has led to a rise in what is called ‘willful defaults’. These are defaults not attributable to the genuine business losses, but rather a refusal by the borrower to pay bank dues despite having the capacity and resources. As one banker complained: “such chronic willful defaults appear to be nothing but scams as personal wealth and assets of the sponsors of several large groups seem to be burgeoning whereas their companies seem to be failing.”

This, by the way, is not just the complaints of one industry. In fact, this has become such a serious problem that parliament actually introduced willful default provisions in the Recovery of Finance (Amendment) Act, 2016. According to the act, a willful default is a “deliberate or intentional failure to repay a finance, loan, advance or any financial assistance received by any person from a financial institution after such a payment has become due under the terms of any law or any agreement, rules or regulations issued by the State Bank of Pakistan; utilization of finance, loan, advance for a purpose other than that.”

Additionally, under the amendments in 2018, the Federal Investigation Agency was empowered to investigate willful default complaints filed by banks.against willful defaulters. If the accused were found involved in any of the categories of willful default, then FIA could submit its report to a banking court.This has not exactly materialized. Sources complain of glacial proceedings, a lack of interest on the part of the FIA, and status-quo orders granted by the high court.

Bad faith actors

Out of the many cases, Profit picked three sample cases filed in different courts against three different companies: Dewan, Tanveer and Ghaffar Group. These groups owe money to several banks. It is typical for companies to owe to multiple banks at the same time, and for the banks to then club together, and either file concurrent suits, or try to make the company operative through restructuring. We use these examples to illustrate not the details of the particular suits themselves, but the interplay of groups and banks when it comes to defaults, and the same problems cropping up again and again.

Before the recent Rs50 billion+ default by Hascol, the Dewan Group has the dubious distinction of being the largest defaulter in the private corporate sector, with approximately Rs36 billion of overdue claims from banks. Much smaller banks and development finance institutions, which had been exposed to Dewan, suffered miserable losses. Even large banks ended up filing suits.

As mentioned before, there is a lengthy judicial process it takes for banks to retrieve their money from defaulters, often between five to 10 years. This gives a defaulter a lot of time to go about their business, while the case is pending in court. So what can a bank do in this situation? Releasing the weak legal system, banks in Pakistan usually try to make the company operative through restructurings, rather than demand their money.

Which is what happened in Dewan’s case. A steering committee of banks was formed to handle the restructuring, particularly in the group’s sugar and textile-related entities in 2012. Fresh financing was also extended. However, the group’s sponsor Dewan Yousuf continued to breach the rescheduling agreements.

Similarly, there is the case of the Tanveer Group of one Azar Saleem Vohra. The group which consists of three entities: Tanveer Cotton Mills, Tanveer Spinning and Weaving Mills, and Tanveer Weavings, defaulted on loans from MCB, UBL, BOP and Summit Bank. Despite making substantial profits from these three companies, the group refuses to pay and is apparently a case of willful default, i.e. refusing to pay back banks despite having the resources to do so. Not to mention that banks have also identified multiple high value real estate assets in the personal name of Azhar Saleem Vohra.

Our third example, the Ghaffar Group has over Rs 2 billion of overdues towards the banking industry. The key sponsor, Noor Muhammad is engaged in the ship breaking business. The group asked for significant loans from different banks and imported scrap ships for shipbreaking in 2014. However, despite several extensions, the group refused to pay back the loan.

The banks allege all three: Dewan Group, Tanveer Group and Ghaffar & Co of willful default and claim that sponsors of these and many other groups use the system to avoid payment and also delay restructuring of their debt by submitting proposals on terms, which were not acceptable to Banks, just to delay the bank’s legal recourse.

Turn to our southern neighbour

So Pakistan has laws, but they are non-applicable, or workarounds can be found instead. Is there another model we could look to? According to one banking industry expert, it would be better to have a stricter foreclosure law, like the Parate Execution, implemented in Sri Lanka. Exactly what is this law? We can tell you that bankers in Pakistan are obsessed with it. That is because this law allows for the sale of the mortgaged property, without going through court proceedings.

How does this happen? The bank demands payment of the outstanding loan amount, which is due at the end of a 14-day final notice. If the customers fail to make a payment, then the bank can pass a board resolution whereby an independent agency or person is appointed that sells the property through public auction. The notice of such a resolution has to be published in at least three national newspapers, and fourteen days prior to the intended sale by public auction.

If the auction is not successful [i.e. nobody wants to buy it], the bank is authorised to purchase it at a nominal price of one Sri Lankan rupee, and with it, the rights of the bank change from that of a mortgagee to that of an owner. If the auction is successful, the bank can subtract all its dues and administrative charges and return the balance money (if any) to the borrower. If the property ends up being purchased by the bank, the bank is required to sell the property in a reasonable amount of time and adjust the amount received against its outstanding.

There are still protections for the borrower: for instance, the customer can negotiate to buy the property back from the bank (once it has been auctioned off to the bank). The borrower can also approach the bank before the auction and renegotiate its terms and get the auction canceled.

But the main idea is to recover losses that the bank may have suffered through the default. Crucially, and why this law is so appealing to many in Pakistan, is that the entire procedure takes between a month to one-and-half months. This is a far cry from the years and years in which cases in Pakistan drag.

The law is not without its critics – ever since its introduction in 1990, the law has been accused of favouring the bank over the borrowers. In fact, as mentioned before, this balance is exactly what Pakistan’s own courts and foreclosure laws have struggled with: what is the appropriate leeway given to both parties?

But the facts speak for themselves: the method has ensured a recovery rate of 90% of the defaulted loans. At least in the Sri Lankan context, the law has proved an effective deterrent.

Where we are headed

Let us return to that figure: Rs829 billion, the non-performing loans of 2020. That figure will rise: after all, consider the future projections of additional defaults against the backdrop of the Covid-19 pandemic. The impact of such large scale defaults will weaken the country’s economy. And even if there was not a pandemic to handle, the problems remain: a culture of willful defaults, and muted housing and mortgage finance in the economy.

The issues of non-performing loans means that perhaps banks simply will not give out loans. Consider the statistics that seem familiar to many readers of Profit by this point: that Pakistan’s financial sector caters to less than 2% of all housing finance transactions, that our mortgage to GDP ratio stands at a miserable 0.6% of GDP. If banks do not feel comfortable ledning out to Pakistani citizens, then citizens simply will not have funds at their disposal to be able to generate more wealth for themselves. In the end, we are all affected.

And the courts, in their misplaced bid to protect the rights of borrowers (or even less ideological than that – just through their sheer inefficiency and complacency) have instead curtailed the ability of a modern financial system to actually do its job.

Great but I really do wish mainstream financial journalists wouldn’t ignore Microfinance banks when writing about the financial sector and lending.

Writing an article on Pakistani banks and default while completely ignoring Microfinance Banks which lend to more people than commercial banks is a glaring omission.

Thank you Ali for pointing this out. You will soon read something on this from Profit

An excellent read, gives food for thought and further research. This is the kind of analytical business journalism missing in other mainstream papers like Dawn, which have unfortunately become cesspools of vested political interests. Readers are smart and have access to more information than ever. In this context, the role of the modern journalist is to curate information, not manipulate it. We see more of the latter in Pakistan, which is why most of the content is either lazy, misleading, or reeks of a partisan bias.

Thank you for the feedback

ZTBL is the only specialized Bank in pakistan in Agri Lending. It is state owned entity. Few years bank ZTBL field staff had powers to arrest the chronic defaulters, Bank was at its profitable peak that time, in Mushraf Era Government siezed powers of ZTBL field functionaries, which makes them helpless and left only one option which is filling a recovery suit after long legal process. People consider ZTBL money as a government money, you cant recover millions of government money just by requesting borrower again and again. Thtx why Bank NPL is increasing day by Day. Please write something about ZTBL causes of Lose.

Excellent effort, masterfully crafted with accurate selection of words. Cronic delay in our Judicial System is the only reason for so high default ratio….

Credit or loan & interest will always be bad!

The short-term euphoria, whether it be in shape of an economic boom and / or to defer prevailing financial crisis will always result in imbalance growth, anomalies in distribution of resources, inflation etc and more importantly, indebting the country in future.

Therefore, the economies (especially developing countries) should think out of the box and must try to completely eradicate Riba / interest from the system to achieve economic goals and to ensure that all sections of the societies live together in harmony.

Above lesson has been taught by Quran & Sunnah, so it cannot go wrong. It is a matter of weak ‘Imaan’ (believe) that we are giving unnecessary preference to ‘man-made laws’, instead ‘revealed knowledge’, and we all have seen in past as well that the former will always lead to socioeconomic injustice!!

The sooner we understand that better it is, otherwise we will continue to grope in darkness.