Consider this picture: the year is 2010. You are the owner of a large textile company in Pakistan, based in Landhi, in Karachi. You face eight hours of power outages every day, but even that’s better than your counterparts in Punjab, where it gets to 12 hours a day or worse. Your factories cannot run like this. Textile manufacturing is a continuous process that needs to keep running smoothly, or else you have to start all over again, which can be extremely costly. And that is if you are lucky and your machines do not start breaking down.

At your desk in your office next to the factory floor, you are staring at that order that you worked so hard to get from Gap in the United States, but now will miss the Christmas deadline for because you have no idea how long it will take to make the clothes given how much your machines have to keep shutting down because of the power outages.

Great. Your engineering manager just came in and told you that what you thought was going to happen has happened: some of your machines have broken down. That is hundreds of thousands, if not millions of dollars in damages, plus reduced capacity for weeks, if not even longer. Oh, and the electricity in the factory and your office just went out again. For the sixth time today.

How can anyone possibly make any money in the textile business?

On your drive home from work, you are thinking about what some of your friends in the textile business have told you about Bangladesh. How the European Union has just granted them preferential tariff access and how the electricity situation there is supposedly a lot better. Some of them have been talking about relocating their factories there, or at least setting up new ones. It is a thought that goes through your head all the time. “Maybe this country just isn’t the place for a textile manufacturer,” you think.

You live in DHA Phase 5, and that is a straight, if somewhat long, drive from Landhi, but you are so stressed that you do not feel like going home right away, so you decide to drive around a bit. You find yourself around Clifton. You drive past Ocean Tower, that new building that is coming up. Right next to it is a wedding hall, but then you notice something. There is a huge crowd around there, but it is not a wedding. It looks like a large number of people – clearly mostly upper middle class – lining up to buy lawn clothing. You remember hearing something about a Sana Safinaz sale today, and think this line probably has something to do with that.

“Hmm… maybe somebody is making money in textiles in Pakistan after all,” you think to yourself.

Then the idea hits you like a ton of bricks and you curse yourself for not having thought of it sooner: why are you not making the clothes that these people would line up for? You are in the clothing business. You have a massive factory that can take ginned cotton and churn out beautiful clothing good enough to be worn by middle-income consumers in the United States and Europe. What is to stop you from selling to middle-income Pakistanis?

The retail pivot

It is hard to overstate just how counterintuitive it was for the textile industry to pivot towards domestic retail consumers over the past decade, after having spent the previous several decades having served mainly as contract manufacturers for brands in North America and Europe.

Think about it: if you already have relationships selling to some of the biggest retail brands in Europe and North America – populations collectively approximately four times the size of Pakistan and economies over 100 times the size, with orders of magnitude more in individual consumer spending power – why would you bother with the Pakistani consumer?

But, of course, that broader macroeconomic picture hides important details. You may have relationships with those brands in developed economies, but you are one of tens, if not hundreds of thousands of manufacturers all over the world competing for the same business, including some in countries with much better infrastructure than Pakistan, such as Vietnam, China, and the Philippines.

In that highly commoditized market, your margins on the product are thin because you have so many competitors all over the world ready to jump in at a moment’s notice if you try to raise prices or cut corners too much.

And, of course, there are those accursed power outages that make it impossible for you to predict how long it will take you to manufacture their orders, and retailers in the US and Europe require just-in-time deliveries, and if they cannot rely on you to meet a deadline, you can forget ever getting an order from them again.

So it is a high-volume, low-margin, highly competitive business where Pakistan’s infrastructure makes it very difficult to retain relationships over the long run unless you have enough pull with the government of Pakistan and enough capital of your own to set up your own captive power plant to supply you electricity directly without having to rely on the grid. Did we mention we now also have gas load shedding?

In that environment, all of a sudden, the Pakistani market starts looking a lot more attractive. Yes, it is less than one-hundredth the size of the combined North American and European markets, but there are also no foreign competitors to speak of. You are the very big fish in the very small pond. If you do not dominate the market, who else will?

There are also other advantages: no more having to worry about just-in-time logistics. You own the stores, and the supply chain, so delays in delivery matter less, and you can always just store a little more in inventory. And because you own your own brands, the margins are much higher than in manufacturing for foreign brands.

Who entered the retail market?

All of this sounds very logical and it makes complete sense that many of Pakistan’s biggest textile exporters would want to pivot from being contract manufacturers alone to becoming owners of their own local brands and retail chains.

But who exactly entered this market? And how well are they doing in it? For this story, Profit examined the retail landscape for textiles in Pakistan, broadly defined, and identified some of the largest retail chains in the space. Ours is by no means an exhaustive list, but we have aimed to have as close to representative a sample of companies in our discussion as possible.

For this story, we are asking and answering the following set of questions: who are the biggest players in textile retail in Pakistan, how big is the overall market, and was the pivot towards investing in more domestic retail a worthwhile endeavor for the exporters who made those investments? In other words, can you build a growing business by moving more and more of your business towards domestic retail?

Our analysis relies in part on data from a large number of companies, but some of the most detailed analysis centers around the case study of Gul Ahmed. That is because Gul Ahmed is both publicly listed and has been the most committed towards moving its business towards domestic retail. Indeed, its CEO has publicly stated on several occasions that his aim is to flip the business mix of the company from two-thirds exports and one-third domestic towards one-third exports and two-thirds domestic retail.

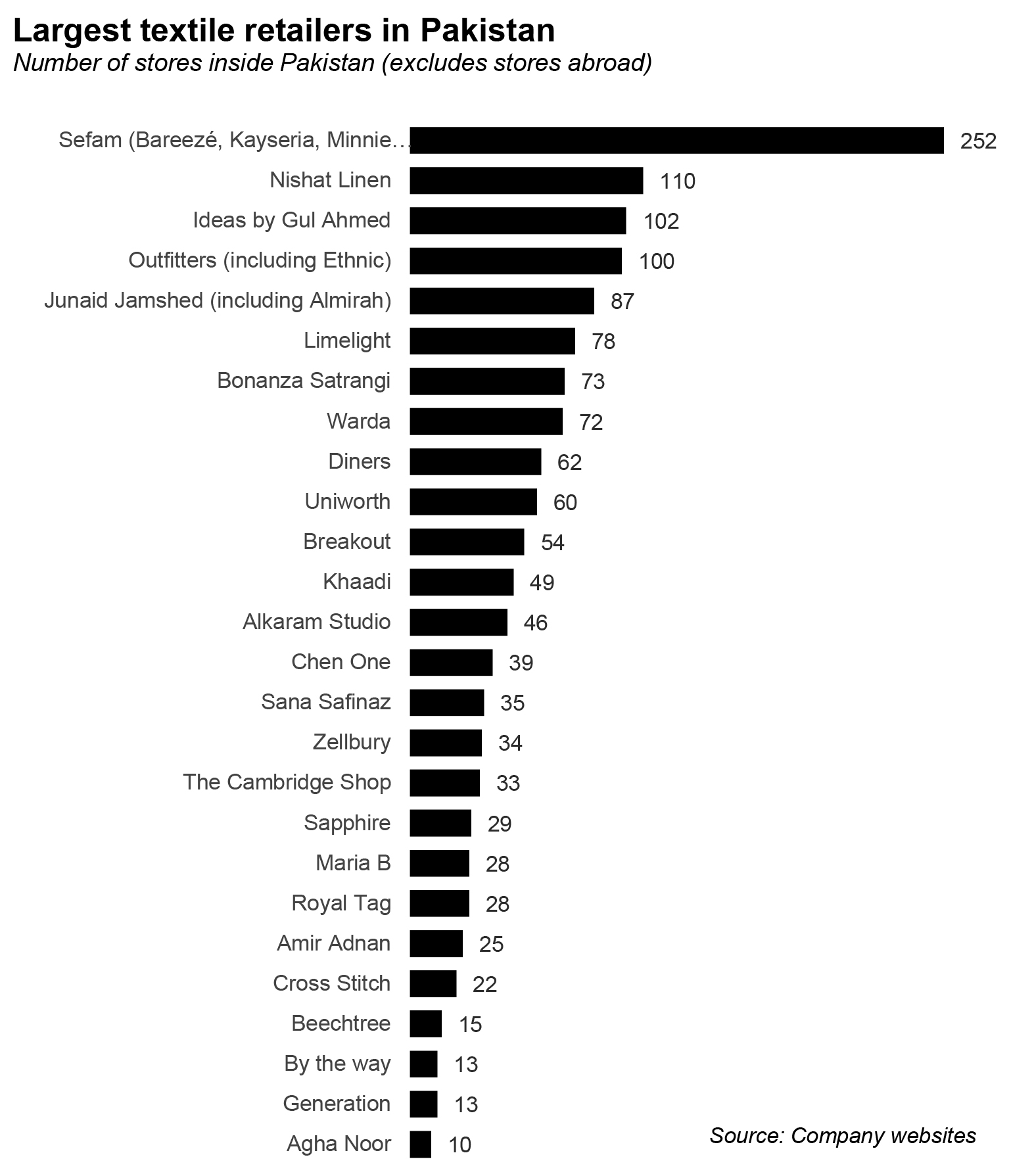

But first, let us examine who the biggest domestic players in textile retail are. Our metric for this is number of stores, which we fully acknowledge is not the best metric to use, because both revenue (total sales) and square footage of retail space would be much better indicators of size of a retailer. However, both of those data points are inconsistently available for many of these companies, which remain private. Hence we have used the data most readily and consistently available, which is the number of stores.

The single largest retailer in Pakistan is Sefam (Pvt) Ltd, a Lahore-based company that owns several brands including Bareezé, Kayseria, Minnie Minors, and Leisure Club, among many others. All told, we were able to find at least 252 stores that belong to the various brands owned by the group. We suspect they are also the largest by domestic retail revenue, though we cannot be certain.

Nishat Linen, a private subsidiary of the publicly listed Nishat Mills is the second largest by number of outlets, with 110 stores. Other than women, men’s & children’s clothing, via their brands which include Nishat Linen, Nishat Linen for Kids, and Naqsh, they have also expanded into home linen and also launched Inglot, an accessories line for makeup, which they started with breathable nail enamel,

Nishat is followed by Ideas by Gul Ahmed (more on Gul Ahmed later), which is in third place with 102 outlets nationwide, and following very competitively behind with only 2 less stores than Gul Ahmed, is Outfitters (including Ethnic).

Outfitters became wildly successful as a brand that largely sold ready-to-wear western wear to men and kids. The company only became relevant amongst women when it launched Ethnic, an eastern wear brand with ready-to-wear as its hallmark. (Update: In 2021, Ethnic became the largest pret brand in eastern wear in Pakistan.) You can read more about Ethnic’s journey here.

Surprised not to see Khaadi in the top few? We were too, until we realized that most other retail chains have a strategy of having a dispersed retail footprint, whereas Khaadi wants to have a smaller number of large stores with a more inviting shopping experience. So it is possible that Khaadi might be larger than these three companies. In fact, according to industry experts, revenue-wise, Khaadi is at the top by a huge margin, where Eastern wear is concerned, with revenues approximated at around PKR 25 billion this year. However, Gul Ahmed disclosed a local revenue of PKR 32 bn last year, according to their financial statements which should put them on top. The third position for last is bagged by Sapphire, with total sales at around PKR 16 bn.

Here is what is most interesting, however: of the top 10 textile retailers in Pakistan, only four are companies whose biggest business line was, at some point, exports. The other six are all companies that have had a primarily domestic business from the very beginning. And even those four have a history of having a branded presence in domestic retail for decades.

Why is this important? Because the Pakistani consumer is a lot more discerning and brand conscious than the boom in fashion design as a career would have one believe. The biggest brands are still the ones that have a long history of building products that the domestic consumer likes.

In other words, if you were previously focused on making jeans for German teenagers, you cannot expect to waltz into the local market and expect the kids at Beaconhouse to start wearing your brand just because your kid goes to Beaconhouse too. It takes time and effort – and a lot of hard work – to figure out what consumers in any market want, and only those that devote a considerable amount of both time and resources to the problem can succeed at it.

The Pakistani consumer plays second fiddle to nobody.

How big is domestic retail?

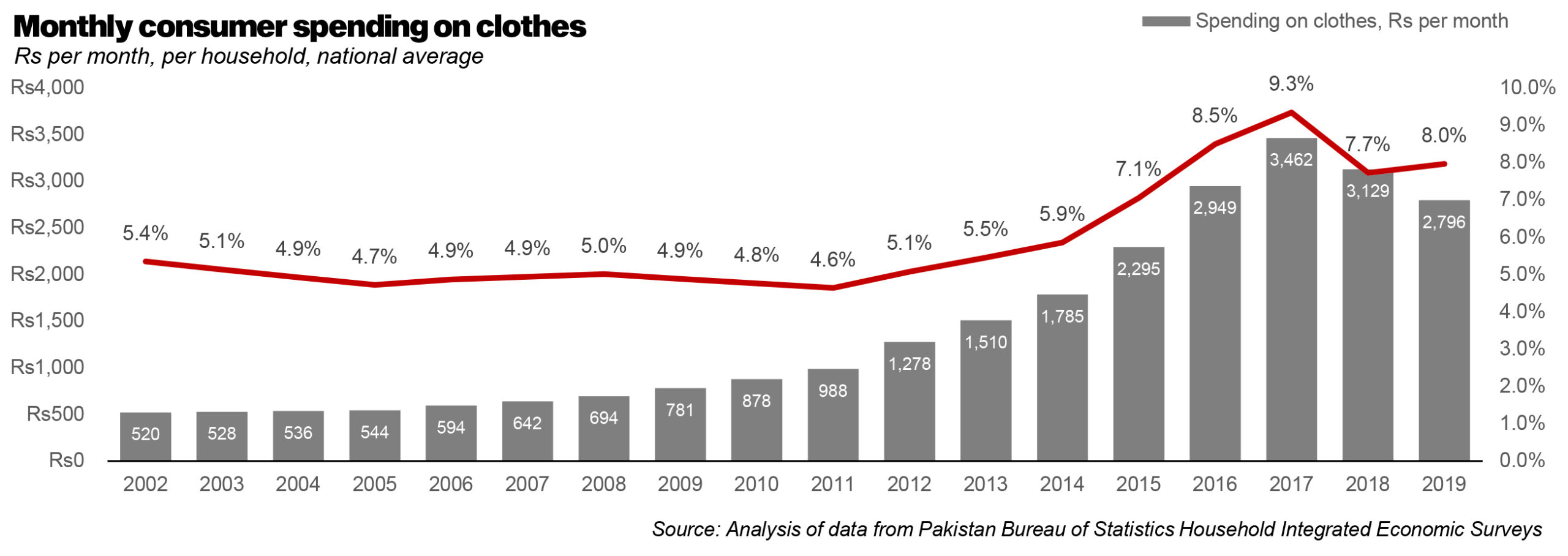

The past three years of a slowing economy have not been kind to the domestic retail market for clothing, but at its peak in 2017, the domestic clothing market was worth approximately Rs1,077 billion ($10.3 billion), according to Profit’s analysis of data from the Household Integrated Economic Survey conducted by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. As of 2019, that number had declined to Rs963 billion ($7.1 billion), a nearly 11% decline over two years, as consumers scaled back on buying clothes during the economic slowdown.

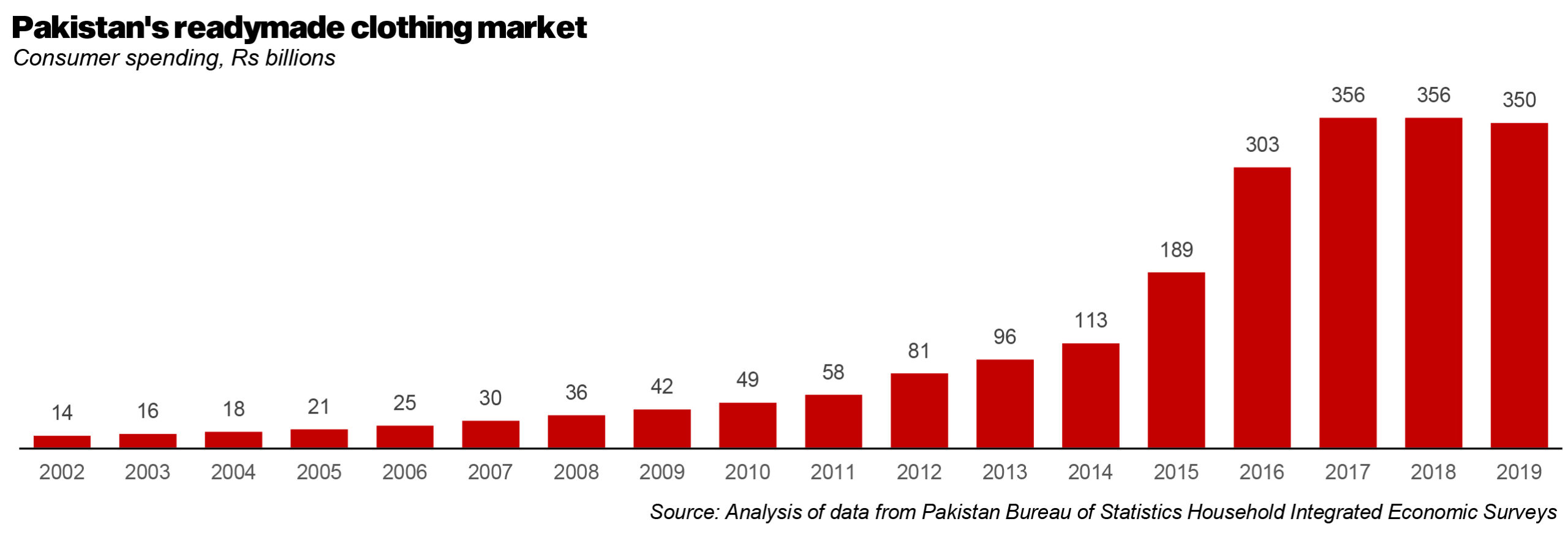

Nonetheless, the part of domestic retail that saw virtually no decline at all between 2017 and 2019 was readymade clothes. This is already the fastest growing segment of Pakistan’s clothing market, having grown at an average of 21% per year over the 17 years between 2002 and 2019. The total size of the market stands at Rs350 billion in 2019, just 1.5% off its peak of Rs356 billion in 2017.

The domestic clothing market is both big and growing very fast as consumer tastes change and as more women enter the workforce, simultaneously gaining both spending power, and a need for more clothes to wear to outside-the-home workplaces. Winning this prize, therefore, is worth the effort for companies that want to compete for a share of the Pakistani consumers’ wallets.

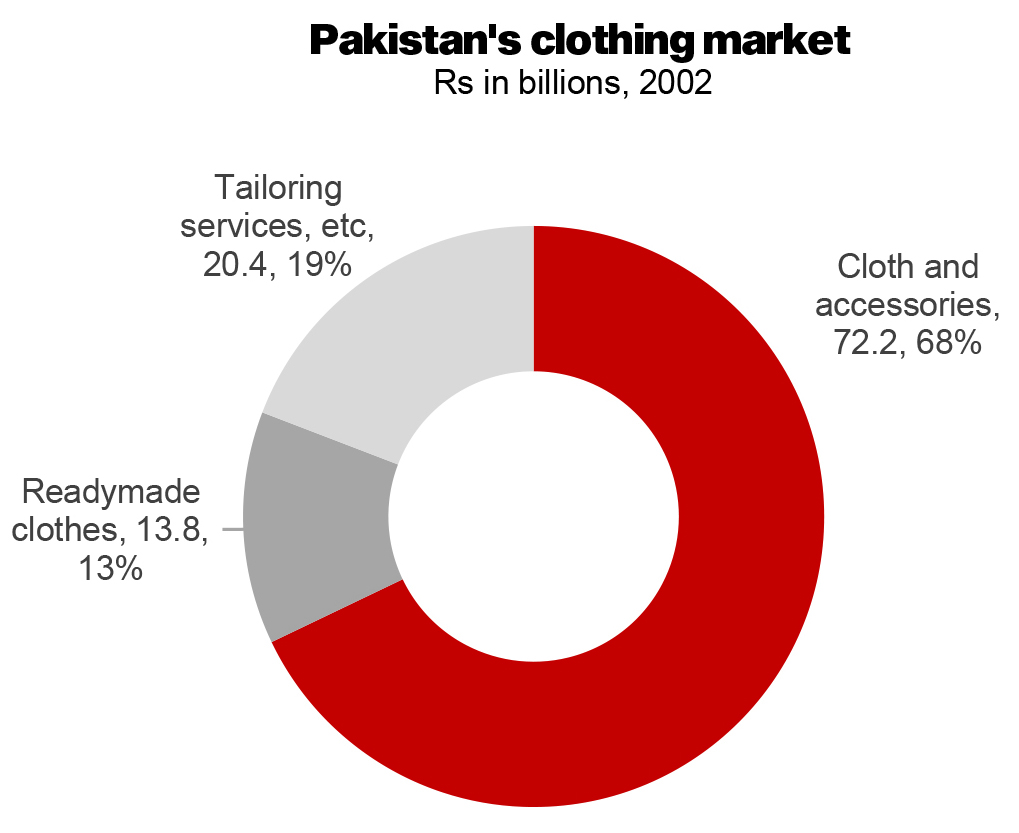

Consumer behavior has evolved dramatically over the past two decades. Buying clothes in Pakistan used to mean buying the cloth separately, then having the clothes custom tailored, and while that remains a sizable portion of the overall market, its share has gone down considerably. Unstitched cloth used to account for over two-thirds (68%, to be precise) of total retail spending on clothes in Pakistan as recently as 2002, and tailoring services another 19%. Only 13% of spending was on readymade clothes.

In 2019, readymade clothes account for 37% of total consumer spending on clothing in Pakistan. Life is getting faster in Pakistan, and people simply do not have the time or patience to have the clothes-buying process take several weeks, especially since both the variety and quality of clothes available off the rack has improved significantly over the intervening two decades. And this goes for ready-to-wear items for more than just women – which include brands such as Generation, Ego, Ethnic, LimeLight, and Jazmin, to name a few – this is a fast-growing category catering to men and children too. In fact, brands previously known mostly for their designer unstitched cloth, such as Sana Safinaz, Maria B, Zara Shahjahan, and even Khaadi, have also started focusing on ready-to-wear lines in their portfolios, making sure not to miss the huge market for kids’ wear.

The shift toward eastern pret wear can also be seen for businesses that previously dealt mostly in western wear. For instance, Ethnic, which is a brand from the same company that owns Outfitters, the market leader in western wear in Pakistan.

Is it profitable to pivot towards domestic retail?

This, of course, is the multi-billion-dollar question, after all. If I am the CEO of a company and I have a certain amount of cash flows and capital available to me to invest, which part of my business am I better off investing in? Which business line will most increase my profitability: the export line, or the domestic retail line?

There is, of course, at least some overlap between the kind of investments required to expand into both. Take the example of Gul Ahmed, for instance. Gul Ahmed is a vertically integrated textile company, meaning they take ginned cotton (slightly more refined than raw cotton) and take it all the way through spinning into thread, weaving that thread into cloth, dyeing that cloth into patterned colors, and then sewing that cloth into readymade clothes.

Investing an expansion of their spinning, weaving, dyeing, and even stitching capacity is something that would work on both the export and domestic retail line. So the trade-off is not that clear cut for at least part of the production process.

After that, however, the needs completely diverge. The export business needs some investment in a foreign sales team, but not much else. The domestic retail business, however, needs one to hire and retain a design team for local designs (export orders require minimal design work from the manufacturer), plus a massive investment in domestic retail outlets, which can sometimes involve buying real estate and building out custom stores.

On the domestic retail front, the textile industry has been helped by the quiet revolution that has taken place in commercial real estate across all of urban Pakistan. It used to be that malls were a concept known in Karachi and Lahore, and barely anywhere else. Now, one of the nicest malls in all of Pakistan is in Gujranwala, and virtually every city with a population above half a million has a sizable mall.

Why are malls important? Because you can then just rent a space, pay an interior decorator to spruce it up, and fill it with inventory and you have a functioning retail outlet. Without a mall, you need to buy land in a desirable location (expensive), build a structure on top of it, and then do the interior decorating, etc.

And given the lack of liquid real estate investment trust (REIT) market in Pakistan, a sale-leaseback – where a company sells a structure it has created to investors and then rents it out on a long-term lease from them – is not really an option. That means that the amount of capital it took to buy the land is simply stuck in that asset. The rise of malls, however, solves this problem.

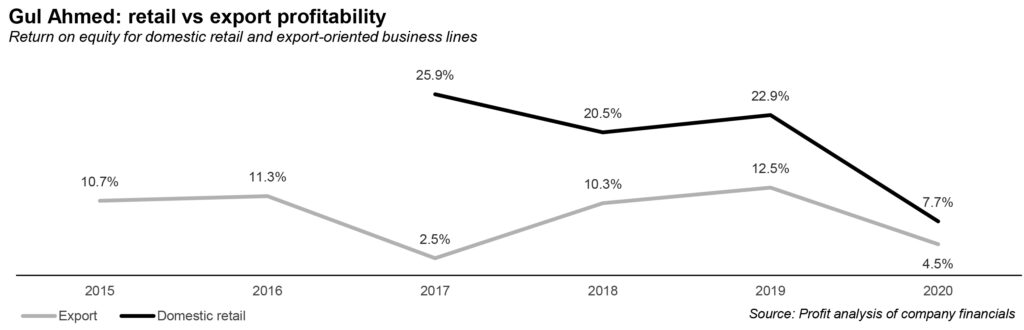

So just how profitable is it to do all of this additional investment in the retail outlet? Is the incremental profit margin from owning one’s own brand of clothes enough to cover the additional cost of running stores? The answer, at least insofar as Gul Ahmed’s financials are concerned, is a resounding yes.

Gul Ahmed only started breaking out its retail business on its financial statements in 2017, so we were only able to analyze four years of data, but in all of those four years, the return on equity from the retail business was significantly higher than that of its export-oriented business. That means that every additional rupee invested in the retail business earned more profits for Gul Ahmed than an additional rupee invested in the export business.

This was true even in the year 2020, when retail lockdowns in the last quarter of the financial year ending June 30, 2020 meant that revenues declined, causing a decrease in profitability. One expects that subsequent, non-lockdown-impacted years will continue to show even higher profitability for the retail business relative to the export business.

So how does the retail business have so much higher profitability? Because when you own your own brand, you get to charge prices significantly higher than your cost of production. Gross margins – the profits left over after incorporating the direct costs of manufacturing a product – for the retail business even in the worst year only went down 25%, and are typically closer to 30% of revenue. The export-oriented business, on the other hand, generally has gross margins less than 10%, and even in the very best of years, this jumps to a maximum of 15% of revenue.

It is true, of course, that distribution costs for the retail business are significantly higher. Running those stores does not come cheap, after all. But the difference in gross margins more than covers for the higher operating and distribution costs.

Will e-commerce change the need for domestic retail outlets?

The pandemic changed Pakistani spending habits, making more people willing to buy online than ever before. So is this rise of physical retail a relic of a bygone era? Our initial inclination would be to say that while e-commerce will no doubt cause a significant shake-up in the way clothes are sold in Pakistan, it will likely not remove the need for physical stores. Clothing is one of those items where even large e-commerce players find value in eventually going for a more omni-channel strategy of having physical outlets as well.

What we will be on the lookout for, however, is a brand that starts entirely online and cracks into the top 10 or even top 5 retailers by revenue after having opened up retail outlets.

No matter which way the market evolves, there is no doubt that investing in serving the clothing and fashion needs of the Pakistani consumer is a profitable business. And the Pakistani consumer demands customized attention, not export rejects.

Disclaimer: This story was originally published on May 31, 2021, and therefore, most of the data analyzed here is up to 2019. However, based on some relevant and important new information since then, the story has been updated to reflect the data up to 2021.

Given the fact the the writer has fairly limited publicly available information on the topic it was a nice read. However for any meaningful analysis one will need to analyze the retail market in terms of its segments (men/women/children).

Obeviously This will work

Quite an insightful article. One dominating aspect of the study reveals that from 2002 the share of the ready-made was 13% and in 2019 it soared to 37%.

It shows multiple changing signs in consumer behaviour. With passing years, more women are becoming work-women and are getting independent with thier own income. At the same time, they may not have the luxury of spending too much time on shoppoing and getting it stiched. Ready-made and the women designer brands have picked up fast with the changing culture.

Indeed, it clearly spells out the huge oporunity for retail brands to position themselves right.

But the success may matter upon the three variables i.e good quality stuff, good aesthetics in design, and most importantly good pricing.