If you thought import duties were taxes on imports, you’re only half right. They are also, implicitly, and powerfully, taxes on exports.

In 1936, the American-British Economist, Abba Lerner developed the idea that an ad-valorem import duty is equivalent in its effects as an export tax. This unintuitive idea, known as the ‘Lerner symmetry theorem’, means that when a government introduces an import duty in a sector to protect it from foreign competition, say, to substitute imports, it is artificially increasing the profitability of domestic firms that choose to sell in that sector, relative to those that choose to sell in (unprotected) export markets. Thus, import tariffs introduce an anti-export bias. Intended to substitute imports, they end up substituting exports instead.

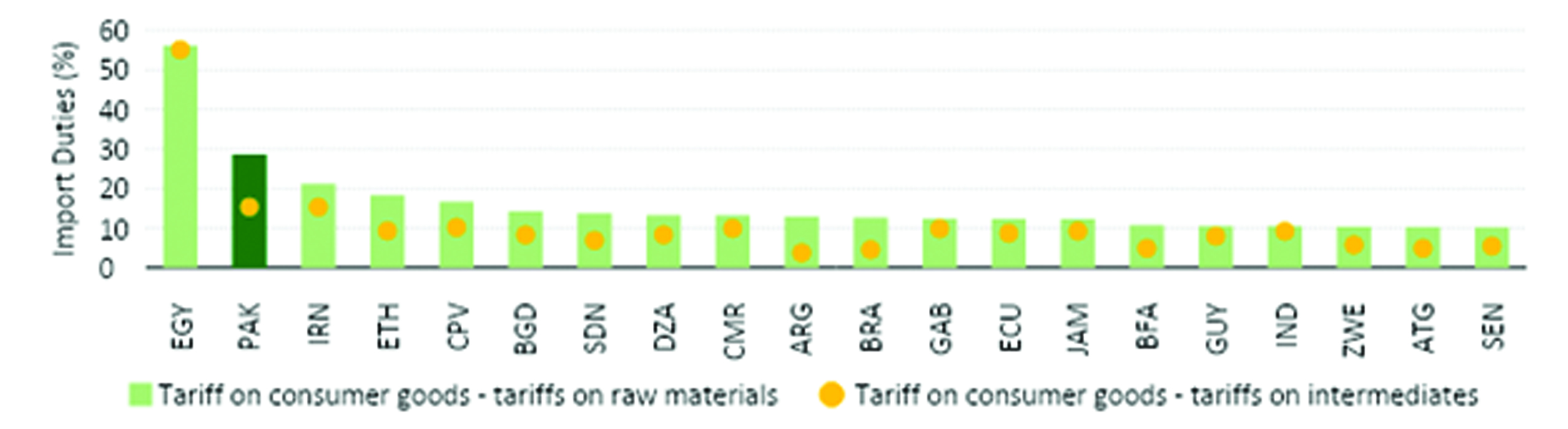

The anti-export bias of import duties is accentuated when these duties are structured in a cascading manner. Cascading means that duties on raw materials and intermediates required to produce a final good are lower than those on the final good itself. Say, import duties on pedals, wheels, saddles, brakes, or frames are lower than those applied on a completely built bicycle. And cascading is marked in Pakistan – actually, Pakistan shows the second highest import duty cascading in the world (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1: Import duty cascading, top 20 countries with highest cascading

Source: Pakistan’s FBR and UN Comtrade

A concrete example can help visualize the effects. Imagine that in Pakistan, the sector producing bikes faces no import duties. Bikes are sold internationally at US$100, and, assuming for simplicity that transport costs are negligible, bikes would also be sold at the equivalent PKR price in Pakistan. If domestic bike producers were to sell at a higher price, import competition would price them out of the market. And if they were productive enough to sell at a lower price, they would export all they could produce and secure a US$100 price in international markets. Imagine also that in Pakistan, out of the US$100 value of the bike, US$67 are input costs and US$33 are value added (as suggested by the latest Census of Manufacturing Industries, CMI, 2015/16 that reports value added in output to be approximately 33 percent). In addition, and again following data from the CMI, of the US$33 of value added, US$8 correspond to wage costs, and US$25 to operating margins (markups, or profits)). If now the Government of Pakistan introduces an import duty of 10 percent on bikes, say because it wants to promote import substitution (but introduces no duty on the inputs required to produce bikes, that is, in cascading), then imported bikes will sell in Pakistan for US$110. Pakistani producers of bikes can choose to sell bikes domestically or export them. If they sell domestically, because the import duty reduced the competition they faced from imports, now they can sell bikes at a price up to US$110 without begin priced out of the market by foreign competition. That means their profits would increase from US$25 to US$35 (or by 40 percent). If the domestic firms decided instead to export the bikes, with the international price at US$100, their profits from exporting would remain at US$25. The cascading import tariff (of just 10%!) has increased the profitability of selling domestically relative to exporting by 40 percent! The import duty has had a magnified and powerful effect on the incentives to export.

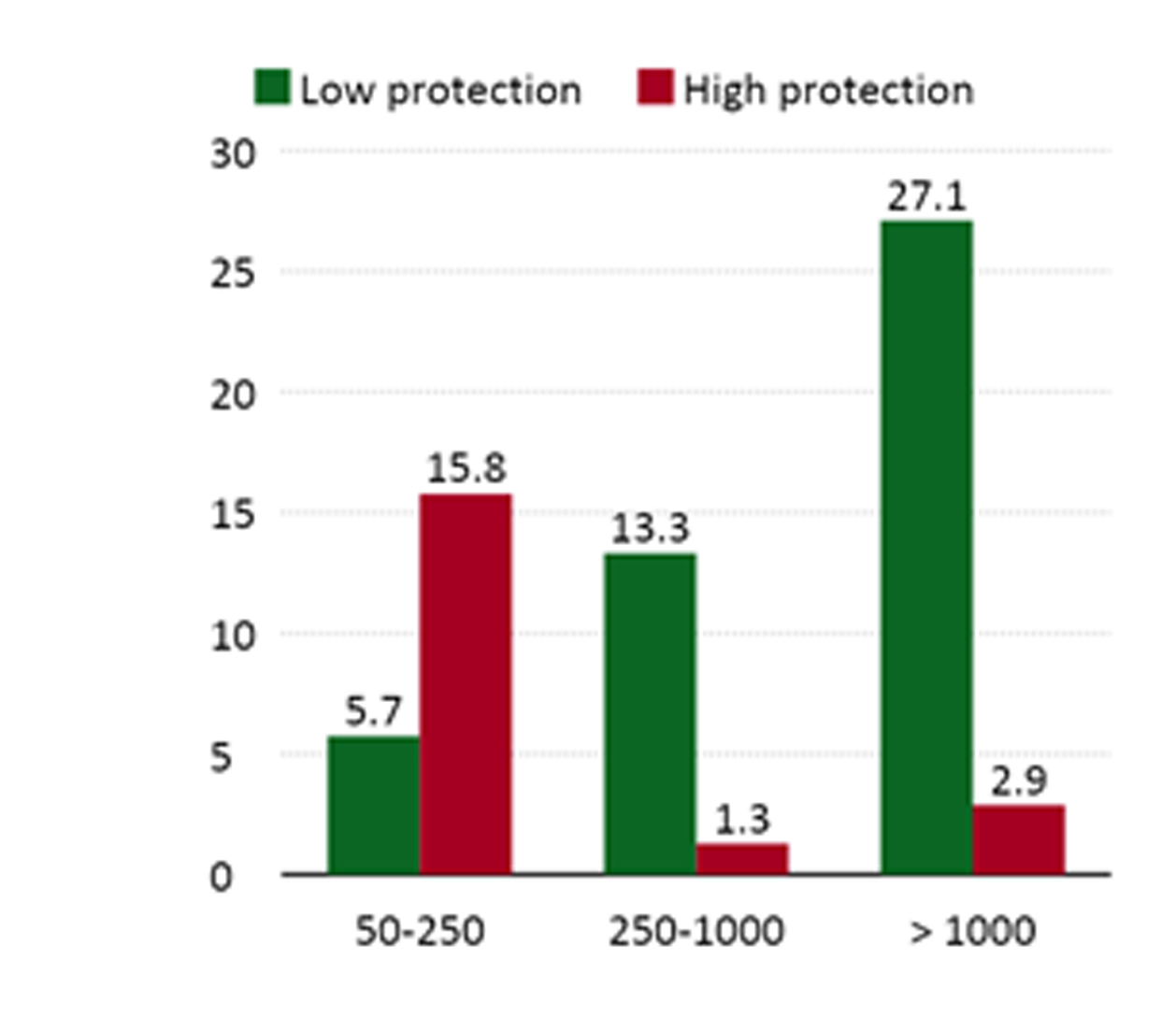

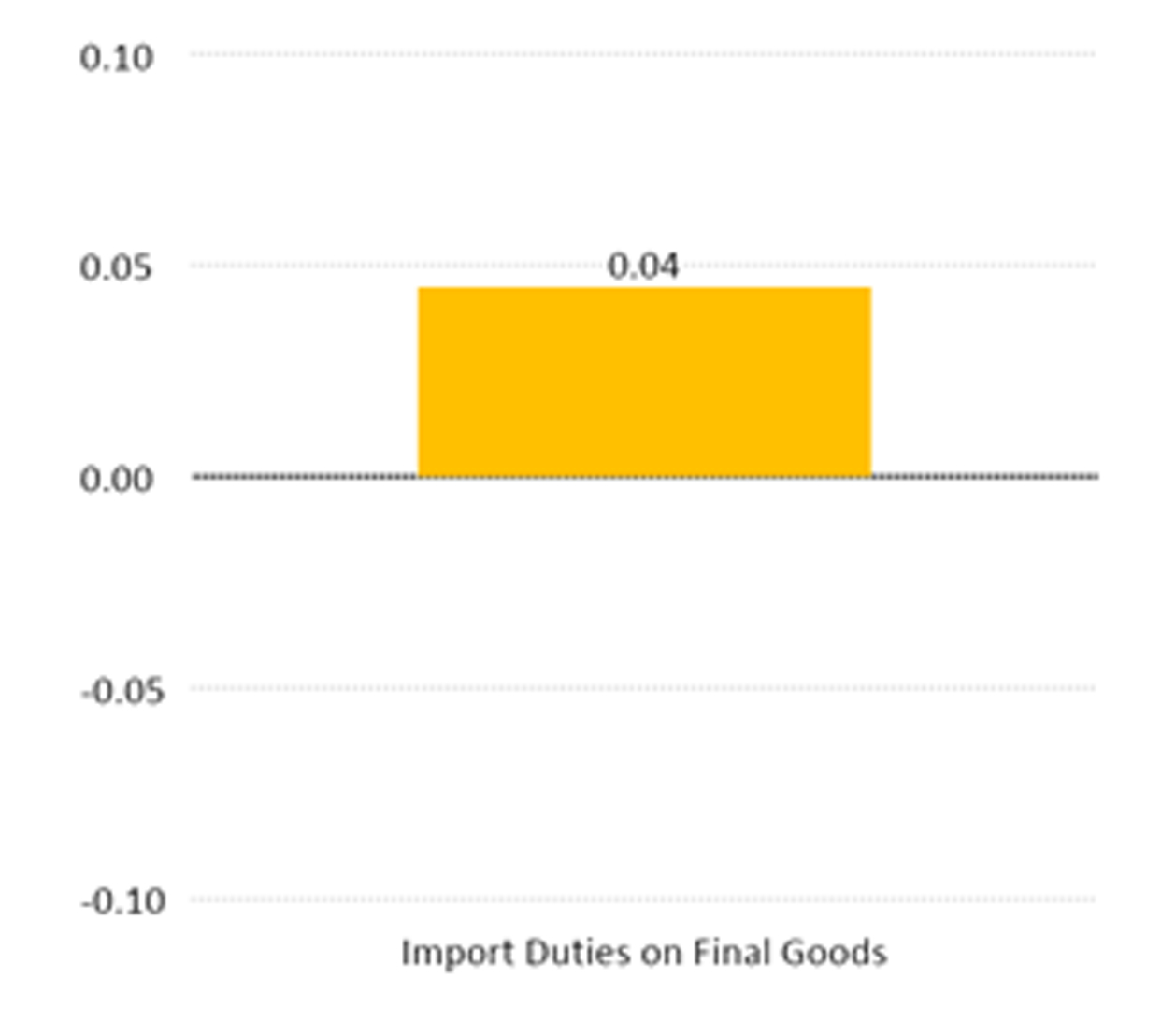

And this is not just a made-up example. Systematic evidence for publicly listed firms in Pakistan shows that, on average, a one percent increase in tariffs in final goods increases the profits of firms producing that final good by 4 percent (Figure 3). It is then no surprise that firms in sectors that face increased protection tend to export less as a share of total sales, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Pakistani firms’ size and share of exports in revenue, by level of protection, 2012-2020 averages

Source: Authors’ calculations. Note: High protection sectors are defined as industries with more than 100 percent effective rates of protection.

Figure 3: Effect of increased protection on markups

Source: Authors’ calculations. Note: The bars indicate the percentage change markups due to a one unit increase in output and input tariffs, which are comprehensive of customs, regulatory and additional duties.

The intended objective of the import tariff cascading is to promote industrialization (and in times of current account deficits, substitute imports). The unintended consequence is that it discourages exports (does not help with the current account deficit), and importantly discourages productivity growth in the long run. This is because cascading allows domestic firms to import inputs cheap but gives them protection on the final product through a high import tariff, so that they do not have to compete on a level-playing field basis with international firms. When cascading is prolonged over time, not only exporting is discouraged, but so is investment in innovation and productivity upgrading.

The author is oversimplifying the effect of import duties. It is important to note three things, which are interrelated, but introduce a level of complexity into such decisions:

1) The author assumes that there are no export rebates for producers in foreign countries, which means that even if the producer of bikes sells them for $100 in the international market, it may be getting a 10% rebate on such export; and

2) The foreign producer may in fact be dumping the goods in Pakistan at a lower price in order to achieve economies of scale domestically.

This means that without the presence of import duties (anti-dumping or general ones), the producers in Pakistan would not be able to survive. It may be noted that regional trade has several cost-advantages including low freight cost of goods, faster delivery times and a closer understanding of the market.

3) Economies of scale must be realized in order for the cost models assumed in the article to operate. Import duties may be structured in such a way that producers are forced to achieve these scales to compete in the international market at a later date.

Thanks for the comment, Shahmeer.

On your points. 1) I’m not assuming there are no export rebates. The argument I make holds with or without export rebates. An export rebate will, however, incentivize exporting, all else equal. Yet, Shahmeer, notice that in Pakistan, import duties average 20% while export rebates average less than 2%. So, export rebates do not compensate (at all) for the effects of import duties. 2) For dumping, there are anti-dumping and countervailing duties that are imposed IN ADDITION to import duties, which are in fact used quite actively by Pakistan (and that add to the anti-export bias. 3) True. economies of scale matter. exporting helps achieving them.

banning unnecessary imports completely will help local manufacturer to achieve the economies of scale and will help them to compete in international market this will also create employment for the locals which will increase the buying power of people

If they were unnecessary, they would not be imported in the first place. If they are imported, is because someone needs them. But more importantly, local manufacturers need technology transfers, they need competition, and they need to upgrade productivity. Import bans bring the opposite: they prevent tech transfers, they create monopolies for domestic companies, and deter innovation and investment. Proof of that is that import duties have been high for a long time in Pakistan and firms have not managed to achieve economies of scale, much less compete in international markets: why would they if they get much higher (monopoly) profits if they sell at home? Import taxes are export taxes in disguise.