Those of you born in the 80s will remember your mothers buying material from Bareeze. The stores glittered with delicate, sparkling work on the softest materials and in a rainbow of colours. There was something for everyone and something for every occasion. The dresses that were eventually made from this fabric were enduring; you could never give away your Bareeze.

Today, the exercise of picking out your cloth to make your clothes, formal and informal, has all but disappeared. It is now about that one ubiquitous word: Pret. The french word for ready. Everything is now ready on the racks for you to try. It has to be convenient. And it has to be affordable. Affordability is the key. With fashion trends changing rapidly year to year, season to season, it’s about buying and buying often.

These days, when you buy a dress, it is more often that not taken for granted that it will be given away next year, or the year after that. Large-scale retailers such as Khaadi or Sapphire, go through four collections every year, most of their stock sells out. Other retailers such as Sana Safinaz, Sania Maskatiya, Maria B, Zara Shahjahan and even Agha Noor, though not all of the same scale, have pret wear collections that are hugely popular, and constantly in demand.

They call it fast fashion.

Life in the fast lane

People want to shop. Zain Aziz, Creative Director at Bareeze Man, in an interview with Profit says that, “as a society, we don’t have a lot of different outlets for enjoyment, which is why people have become so shopping-heavy,” adding that “the experience of going out and shopping as an activity gives them something to do.” When we shop so often, we cannot spend on very expensive items, especially since we are buying things we can dispose of easily. Aziz equates this ability to be able to go out and buy stuff to a dopamine hit.

“Everyone is following fast fashion,” declares Samiullah Khan, CEO at OAKs by Star Textile Mills. “As this impacts quality, even if there are people who wouldn’t want to keep replacing their clothes with new ones, they have to keep doing it.” Market trends change fashion so fast, consumers have to follow.” It is a strategy that works for producers but they are not alone in this, he explains.

“The influence of social media also cannot be ignored,” says Khan. The greatest pressure is on those between the ages of 18 to 20. “So, it’s not about whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing. Selling more means producing more and selling at lower prices.”

Do you remember Khaadi of the early 2000s? Remember the androgynous kurtas, in gorgeously bright solid colours, the lose cuts and handy pockets, and the deliciously soft khaddar that was perfect for both Karachi summers and winters?

Fast forward to Eid in 2022, the Khaadi store in Dolmen, Clifton, Karachi, was faced with several complaints about both the quality of fabric and workmanship of their formals. A regular Khaadi-goer said she bought something for a mehendi and three other people came wearing the same thing to the event. She then proceeded to show much of the work had frayed after being worn just once. Her karigar in Gizri, Karachi promised to fix it for her, she said, feeling relieved. But what’s the harm if it wasn’t expensive, right? Kya bura hai?

Wrong.

While fast fashion may be affordable, it comes at a price beyond the tag you glance at in your favourite pret store.

Simply put, producing more means more pollution, as Khan says.

Fast fashion and its discontents

While Aziz understands the excitement that comes from constant shopping sprees, he is not for it. “I hate fast fashion, I abhor it, I hate what it does to the planet.” Fast fashion is symbolic of what is happening to society. We as a company are not about fast fashion, we don’t cut quality, we don’t under price, we want people to love what they buy. If you drop ketchup on your waistcoat, we will replace that panel for you. We want it to last forever, we want it to be a considered purchase that stays with you. Bareeze is the same, its prices don’t qualify it as fast fashion.”

The truth of the matter is, clothes need to keep up with changes in both global and local trends. When planning for the next season, being able to correctly predict what styles will cut it and what won’t is a specialised skill. If you get it wrong, you’ve had it, says a designer at Sapphire, wanting to remain anonymous.

A management official at Outfitters says product forecasting is very important but extremely challenging. “We have big volumes, if we get forecasting wrong then we have to put everything on discount to make it sell fast.” Obviously all of it doesn’t sell, so then they dump.

And here lies the rub.

Firstly, brands’ forecasting needs to be accurate so they dump less, says the official. Secondly, the fabric of all that is being dumped should be decomposable otherwise it destroys the environment. The dumping sites around Karachi are proof of how, in Pakistan, no one really seems to be thinking of sustainability.

A mill owner, on the request of anonymity, however, disagrees. “Everyone is thinking about it. But how is this our responsibility?” he asks. “The government should have a plan.” As an afterthought, he shakes his head, adding: “we don’t have the luxury of thinking about such things, we have a business to run.”

More on that later. First let’s get to some of the issues.

The polyester problem

The mill owner admits that fast fashion in many perspectives is “very bad”. First off there’s the issue of the material widely used to fuel this fast fashion revolution.

“Polyester is the primary driver of fast fashion in the world and has now come to Pakistan,” he says. It is cheap and durable and fits right into the fast fashion matrix. The magic ingredient, if you will. But polyester, of course, is basically a plastic based product, and unlike natural fibres requires lots of energy to produce. And when you dump polyester… well, you get the picture.

There has been a recent surge in western wear and the certain styles and cuts that have been trending on social media. When you see something being worn by everyone you want it, too; then you share your pictures on social media; then you can’t bring yourself to repeat those clothes over and over again, because how many times can you share pictures of yourself in the same clothes? At this point it doesn’t matter whether the material is eco-friendly or whether it was made to last. The point is that you can be as fashionable as your favourite influencers.

The mill owner says that you have to look at what people want, and you have to give them that. He believes women are the primary drivers of fast fashion, while, ironically, also being more aware of what is eco-friendly and what isn’t. “But when you’re making clothes for people whose average salaries are around Rs 100,000 or so, you cannot be thinking of the environment, unfortunately.”

Lulusar has brick and mortar stores but their e-commerce is booming. So many of their products have polyester in them, but people are buying away. Limelight, another popular brand, has lawns that don’t last more than a season. The cloth loses shape after a few washes but their sales have not fallen despite anything. An influencer who often models Lulusar’s clothes on her page says, “so what if a button or two falls off, my darzi will put it back, their clothes are trendy and affordable, and I don’t want to keep these around forever.”

What happens when she gives these away? Eventually her dresses will land up in one of the dumping sites, just more non-biodegradable items to add to the heap. “God, no one is thinking this far and this deep,” she replies honestly.

What is sustainable fashion?

Murshed Alam Qureshi, Director Business Development and Sourcing at MAQ supplies, has been formerly associated with Levis. He says that, from a layman’s perspective, anything that is produced using biodegradable material is great and sustainable. But there’s a lot more to it. “The carbon footprint is part of the trajectory of a product, materials travel from one country to another, there’s packaging, tags, everyone has to work together to make sustainability happen.”

Deen and Keeno, an upcoming but small-scale e-commerce brand, makes sure that only one plastic bag is used throughout the life of a garment, and packaging is in a canvas bag. The material that is sourced is sustainable cotton, no polyester tags are used. Instead, they stamp their brand on the back of their shirts or pants. Amongst some of their very popular items are their bomber jackets made from either pure leather or their Banarsi bomber jackets with the finest silks. Nadia Zafar, who owns the brand, says she didn’t start this because she wanted to make money. “I wanted to make cool clothes, rock-star, androgynous looks. My girl is tough.”

But many believe that sustainable fashion is not sustainable for businesses in Pakistan. When something is ‘sustainable’ it automatically becomes expensive.

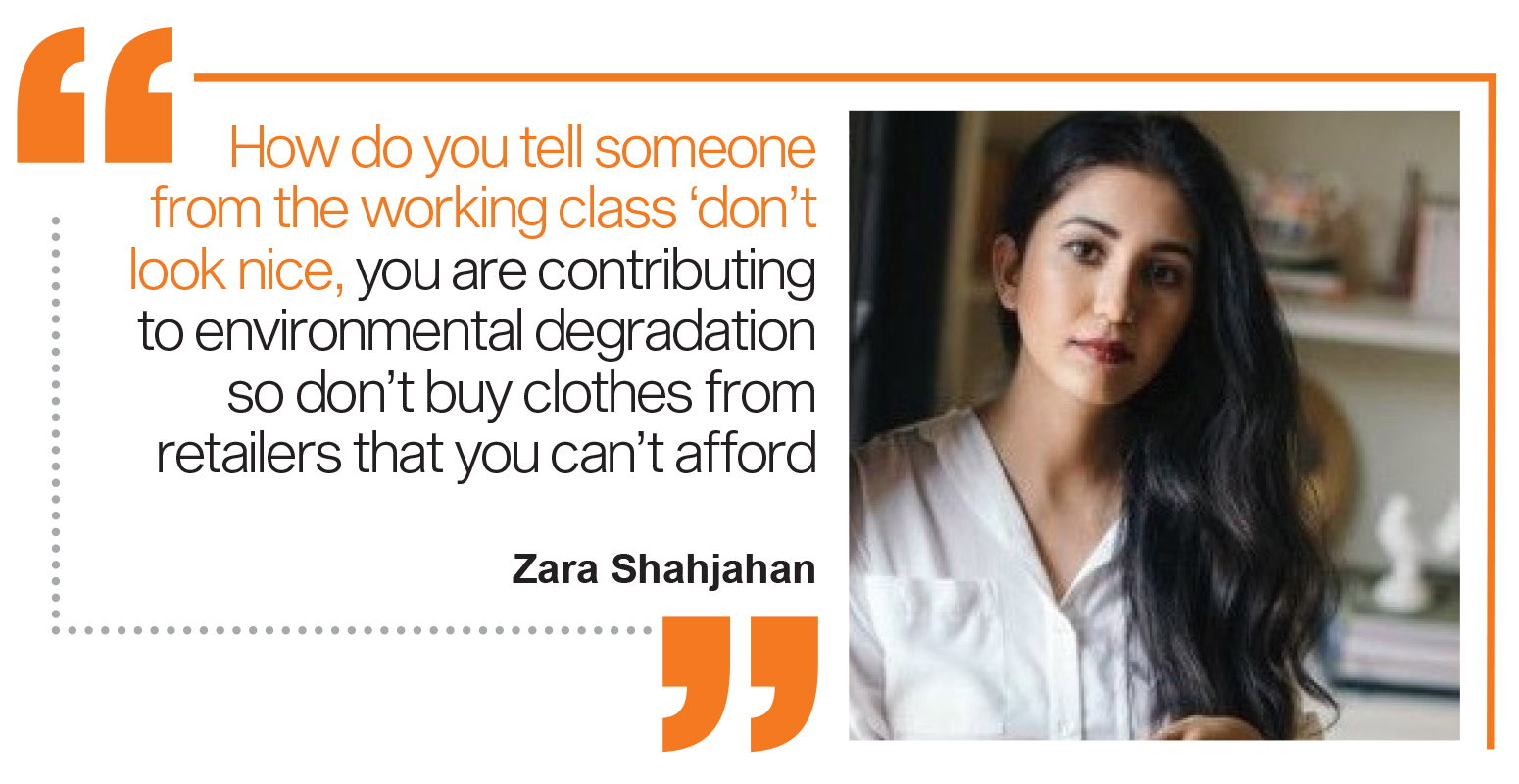

“How do you tell someone from the working class ‘don’t look nice, you are contributing to environmental degradation so don’t buy more clothes,’” Zara, from Zara Shahjahan, says.

It’s not as if retailers and designers aren’t conscious of the fallout of fast fashion. Many retailers try sustainable fashion, but it isn’t quite working out.

Shahjahan’s husband, Saif Rehman, who is the COO of the company, talks about Jehan, a small side project that seems quite dear to him. The online store supplies sustainable cloth that uses only vegetable dyes. “I have insisted on using turnips, it’s very difficult but that’s also why it’s on such a small scale. It is less expensive than our bridals but more expensive than our pret line.”

Wasif Sikander Butt, Director at Maria B, says mass production cannot cater to such niche-market demands. “For example, I want green cotton, cotton that isn’t heavy in pesticides; but I can’t do much about it. How much green cotton is available for me to buy?” He adds that consumer demand shows people don’t care for ‘slow fashion’; it is consumer behaviour that has to change for any such improvement to be brought into the production of clothes. He does not seem to be in favour of polyester, of course. “Any synthetic oil-based product may have a great shelf life but it will not deteriorate. It will go into landfills. Cotton and viscose, at least will disintegrate.”

Even Zafar very candidly admits that this has been possible because her father owns the factory that produces her clothes. “A small corner has been set aside for my stuff and we operate from there. Even then, it is not sustainable through and through. “The science for that isn’t available right now,” she says.

OAKs’ Khan says the same thing. He believes Pakistan does not have the technology to make eco-friendly clothes. Both him and Butt explain how even the west’s ‘sustainable’ clothing caters to a very small market. So small it is negligible.

Usually the response to this is that efforts are being made to use paper or cloth bags instead of plastic. “But the biggest contributor to environmental damage is dyeing and printing, and nothing much is being done about that,” says Khan. Recycling is being done to some extent though, he says.

Small steps

Many other companies are also looking to do what they can. “Change is slow and the steps are small but we’re willing to start the conversation at least,” says the mill owner.

The Sefam Group, under which Bareeze falls, is also aiming to stop the single use of plastic in their supply chain by 2024. Presently, Bareeze has started sourcing all its material locally to help with sustainability.

Zafar believes recycling could reduce waste, almost to the point that more clothes wouldn’t need to be made.

Rashida Rana, Manager Environment and Compliance at Naveena Denim, says this is already being done in the export industry. “Nowadays, the textile sector in Pakistan, especially those exporting, are playing a leading role in creating sustainable practices.” Focus is on water and energy. “No one will buy from us if we don’t follow strict protocols given to us. While the local sector also has its own laws we have to be ZDHC (Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals) compliant otherwise we will not get certification or will be banned.” She admits that there are chemicals in everything but new machines use less water or there are dyes that have reduced chemicals, even the raw materials used for denim have to fall within the purview of ZDHC. But being sustainable requires a lot of investment, and maybe everyone isn’t willing to put in that kind of money.

“In Pakistan, the seth mentality dictates that if there is no money in something, why should we do it,” Qureshi says, making a valid point.

But Shahjahan disagrees with this criticism. “This is like telling us to not make any money.” Everyone is contributing to sustainability, she believes, her brand does so in their designs – classics that will stand the test of changes in fashion in the years to come. “We in Pakistan are not contributing to global warming at all, our contribution is negligible. We need to keep the economy running, make sure we provide jobs for people. Why the hell are we even doing this if we are not allowed to make money?”

She also believes that building cottage industries to support and enable sustainable practices is the job of the government.

The customer’s role

The thing to understand, says Khan, is that the retail sector thrives on excessive consumption. There will always be an inherent contradiction.” You want to produce more so you can’t produce great. Economies of scale will make it too difficult. “Other challenges include the fact that organic dyes aren’t the same, colours are sometimes not as vibrant and so on. Using clean energy, which, in fact, is advantageous to factory owners, using machines that use less water and other such factors need to be taken into consideration when we talk about waste and environmental degradation. Unless the consumer decides they want to make a change, nothing will happen, he iterates.

Zafar believes that a consumer will buy something as long as it is unique. And in the interview with the management official mentioned earlier, the same points had been made. The consumer is looking for something that is fashionable and easy to buy. “Consumers are looking at cuts and styles, the entire focus is on how a shirt fits,” he explains. .

But, because you can’t keep buying expensive, do you compromise quality so you can buy more? It would seem so.

Alizeh Pasha, a popular blogger and fashionista, shakes her head at this. “We need to stop demonising fast fashion,” she states. “Why is affordable fashion so bad? If there is someone who can’t afford YSL, but finds something just like it at Zara or H&M, they should be able to buy it and wear it.”

She goes to explain: “Look, we need to make fast fashion sustainable. Repeat your clothes as much as you can. And buy things that will last at least a few years. This means start shopping intelligently.” Since print fads change fast, she has switched to solids. Also, cuts change a lot so maybe one could stick to those that may not be drastically different from what is trending, she adds. She encourages everyone to watch Hasan Minaj’s episode on The Ugly Truth of Fast Fashion on Youtube.

The new economic headwinds

The fashion retail industry is also facing economic headwinds sweeping across the manufacturing landscape of Pakistan, which has everyone hunkering down for a long haul of survival. The strategy that many of these pret brands have adopted – lower margins but higher sales – is under review.

According to one industry insider, who did not want to be named, the customer’s ability to buy regularly is set to be hit by the current economic climate. Pakistan is faced with the highest inflation in decades, the currency is down, and monetary tightening is prevalent. Pakistan has been through lots of boom and bust cycles, but the current one seems to be here for an extended period. So businesses have to adjust to a reality that once-eager customers just may not have the buying power to patronise the myriad different lines that come out multiple times a year. The ability to rely on customers whipping out their credit cards to go on shopping binges of cheaper fast fashion products, which they would not mind tossing away quickly, meant that you could count on bulk sales making up for smaller margins.

The insider said that there is a high possibility that this may necessitate a change in strategy. What will be the change in the strategy? Well, the insider believes it could be a move back to higher margins on more expensive products that will last a longer time. So that dress you buy from your favourite retailer may just last you a lot longer, and may not be ‘outdated’ as quickly as before. That may be bad news for fast fashion, but perhaps good news for the sustainability-inclined that had given up the fight against excessive consumption.

We’re lucky that irony never goes out of fashion. Hold on to your kurtis.

Nice article! Thanks for sharing informative post Keep posting

My husband and I are another successful client of Cyber Genie Intercontinental among many. I read countless positive reviews about how they have been using their cyber expertise to help people achieve their happiness back by recovering their scammed or lost Bitcoin and assets from fraudulent and posers of Cryptocurrencies trading companies. After reading many of the wonderful services they render, I had to contact them because my husband was seriously defrauded by some Chinese bitcoin miners, it all ended in goodwill as we were able to recover what we thought we had lost to scammers. Contact them on [ Cybergenie AT cyberservices DOT com ] WHATSAPP [ +1 ] 2.5.2-5,1,2-0.3,9.1 ] and help yourself from depression.