Let’s play a game. Profit wants you to look at any video of a new locally manufactured car, and count the number of times the reviewer presses down on the car, knocks on any of the panels, inspects places that none would ever really inspect, and says the words “They did not disappoint.” Most acquainted with the automotive space know why they’re doing this, but to the casual viewer it’s nothing short of circus gymnastics. So, why do they do this?

They do this because they’re trying to inspect whether a locally made car, known as a completely knocked-down (CKD) unit, is as good as its imported counterpart or rivals, known as a completely built-up (CBU) unit. Everyone at this point knows that Pakistani cars are not the best in terms of quality. Those who disagree are more than welcome to scroll through PakWheels or other comparable websites and try not to suffer in agony when they outline the premium that Pakistani buyers pay on average for the honour of getting fewer features, or an outdated design. Or all of the above in some instances.

Once you’ve recovered from the agony, you’ll see that the responses for why this is the case to be quite generic. They mostly boil down to: The industry is either still growing, it doesn’t have the scale like its rivals in those aforementioned social media posts, or our companies are just evil. However, as a customer this explains nothing. The more savvy amongst us will tell you to go and look at the customs codes, industrial policies, and productive capacities to make a fair comparison on the basis of total factor productivity. However, this makes no sense to most people and requires far too much effort than anyone’s willing to put in. Thankfully, Profit does have the answer to all these verbal gymnastics that people go through to explain the matter.

The answer to the question boils down to three factors: our market is simply not big enough; it is unlikely to become big enough anytime soon as it lacks the capability; our industrial policy incentivises and encourages this entire mess.

Now let’s get on with the more detailed answer.

The premise of our agony

Firstly, to have a good car, you have to ask what makes a good car company, and in our case an entire sector? Now this might sound rudimentary but it’s important, bear with us. “Having a successful car industry requires you to have scale. You will either need a large enough domestic market or be integrated into larger markets. You also need to have upstream industries such as metal or rubber that will feed into your industry,” says Dr. Ali Hasanain, Associate Professor at LUMS. Now the question is, where does Pakistan stand on these metrics? Furthermore, if we are comparing Pakistan with other countries, who are going to be these countries?

The countries that are used to benchmark the progress of Pakistan’s automobile industry are ”Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and India,” says Asim Ayaz, General Manager (Policy) at the Engineering Development Board (EDB)

So far so good.

Now, let’s start off with the most basic of things. It is almost impossible to compare the cost of producing a car in one part of the world with another because of the sheer opacity. A single car is made of tens of thousands of components that are sourced from different parts of the world. No one, other than a company itself can reveal the difference in the cost that they incur in manufacturing the same automobile in two different markets. You can try to conduct the exercise for yourself, but trust us when we say that it will take more than a while to do all of this. However, a relatively easier way to gauge the difference in cost would be to compare the prices in different regions as it is reflects in the final cost companies incur in different markets.

Profit had previously inquired with industry sources about the ideal gross-profit margin (GPM) that companies aim for. “We set our prices to achieve, on-average, a GPM of 15% above the cost of assembly and import for the CKD and CBU units respectively,” said one of them. Muhammad Faisal, President of the Automotive Division at Lucky Motors Corporation, says this 15% is “hefty”. So use this as an upper bound and backtrack, for whoever does want to get into the mathematics behind this. This is where the fun, and education, now starts.

Now as customers, Pakistanis probably pay the price in accordance with the upper limit of that GPM. We’ll explain why we say this later. However, more importantly in determining the price to features provided that a car company chooses to employ comes down to a macroeconomic variable: The number of cars it can theoretically sell.

Size matters

Let’s get one thing straight, entering the automotive business is not for the faint of heart nor those with tight purse strings. Hyundai Nishat is estimated to have incurred a cost to the tune of $400-500 million in 2017 to set up shop. The day-to-day operations of managing your automotive plant are also expensive. How expensive? Well, let’s just say that companies in Pakistan shy away from revealing their actual costs, however, they do offer something else in return; the fact that they need a certain volume to sustain production.

Profit has documented the innumerable instances of companies that have declared non-production days on account of the lower volume they had this year. In simpler terms, they need a certain fixed amount of units to be able to actually be operational. Otherwise, it’s more expensive for them to keep the lights on. Herein lies the first of our aforementioned premises.

Volume is truly a magical word in the automotive world. “Volume is one factor. Taxes and duties are another factor,” says Ayaz when asked as to what are the main reasons for why Pakistanis cannot have nicer cars in comparison to their regional counterparts. Thankfully for us, those aforementioned social media posts show prices exclusive of taxes. We’ll get to the duty part later. So, volume. Pakistan does not have much of it.

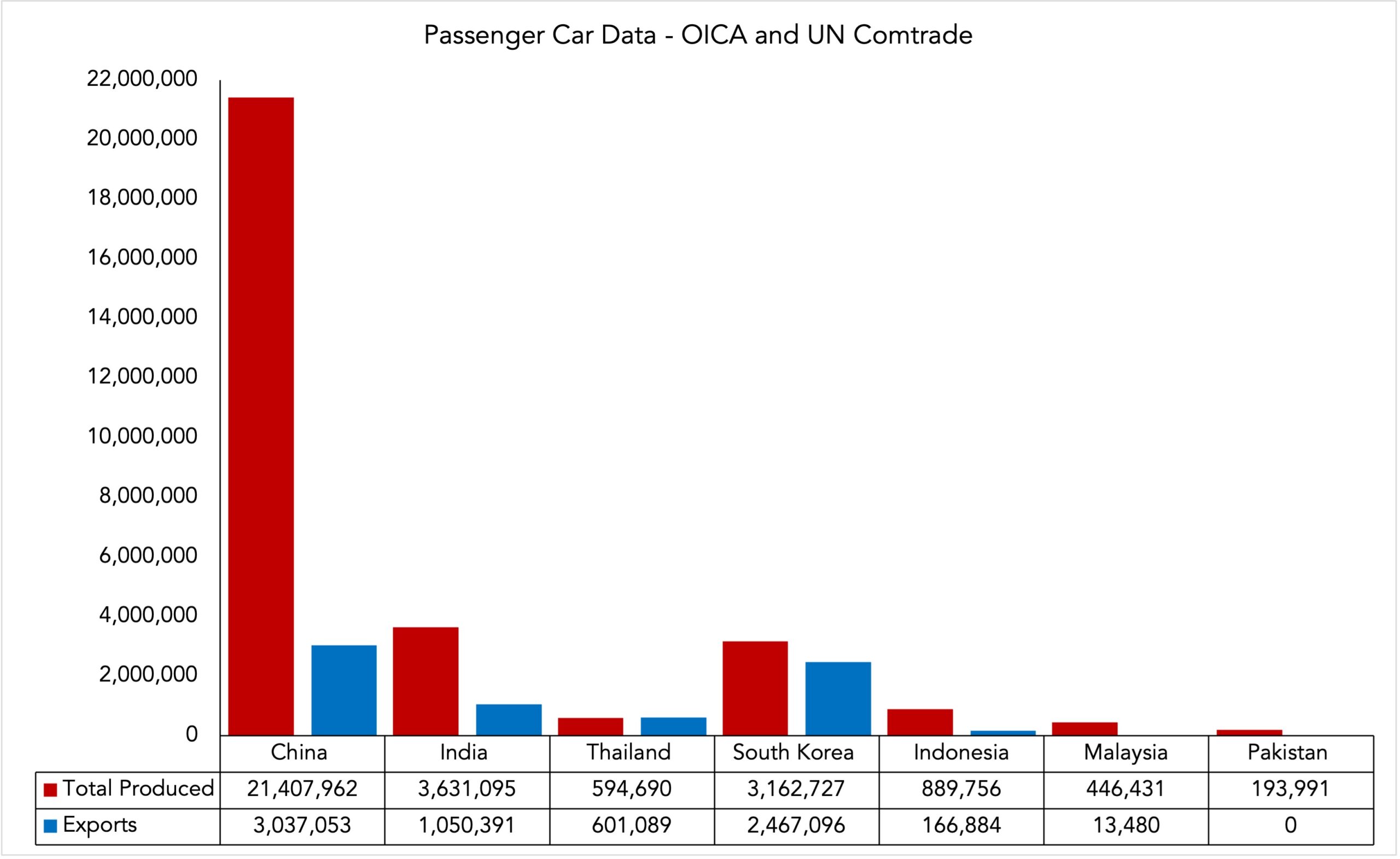

Remember the countries we identified? They produced an average of 1,390,493 cars in the calendar year 2021, based on data provided by the International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers (OICA). This was 7.17 times higher than the 193,991 cars that Pakistan produced over the same period. Similarly, more advanced automotive markets such as South Korea and China have produced 16.3 and 110.36 times more cars than Pakistan respectively over the same period. Ouch. But sit tight because it gets worse. Let us explain this double whammy.

The importance of volume is that companies have a hierarchy in their cost mechanisms. The fixed costs of setting up shop, i.e. that $500 million, take precedence. Now companies can either make 100 units in their plant or 1,000 but the fixed costs will remain the same. Therefore, companies like to opt for the latter to reduce their cost per unit. The more they make, the more it goes down, and the more units they can sell to recoup their investment. Economies of scale. Thus, the more the volume, the cheaper it is to add that auto-dimming mirror which car companies still categorise as a ‘feature’ in 2022. And vice versa.

So, Pakistan lacks domestic volume to sustain a car industry in a similar capacity to the other aforementioned countries. That’s not an issue per se, because other countries also face this problem. It’s only China, and India to a lesser extent, who’s industries were driven by their domestic markets. Other developing countries that built their car industries did so through the second point Hasanain mentioned: Integrating into a larger market.

Exports from Mexico primarily target the US market under NAFTA whilst Thailand has become a location for supplying ASEAN. The Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, Romania and Poland became locations for exporting to the EU. When common trade zones remove customs walls, competition for investment is guided by comparative advantages in production costs. Without membership of a large economic zone in which duty-free internal-market trade exists, no developing country has yet succeeded in entering export markets for cars on a significant level.

So, how many has Pakistan exported? Pakistan has only exported one singular car, till date. Profit asked Danial Malik, CEO of Changan Master Motors, about their plans for exports after exporting Pakistan’s first car to which he has not responded yet. Needless to say the prospect does not look very promising at the moment.

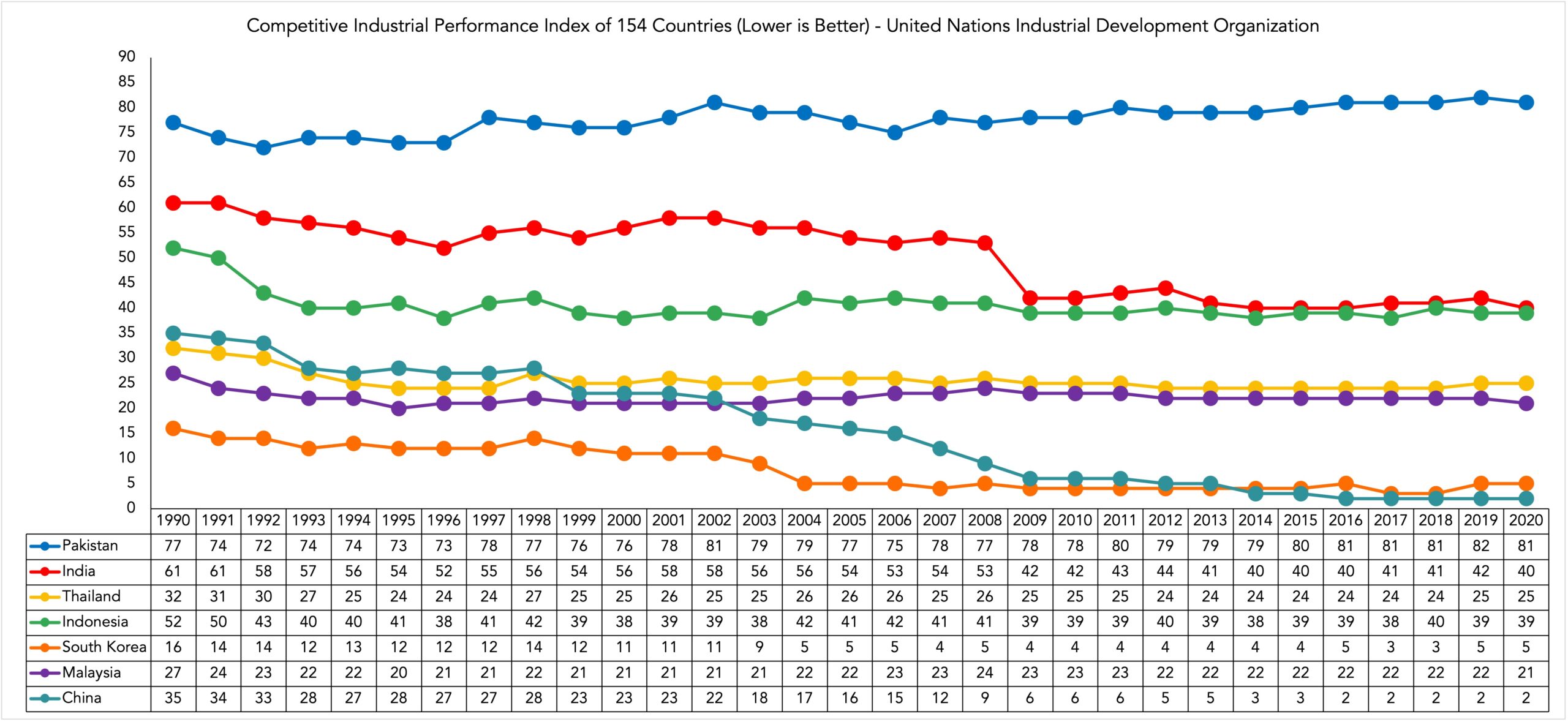

Will we be able to export? That is a good question, and something that’s on the mind of everyone relevant to the industry. It’s unlikely. Now companies might critique the metric of comparing cars directly from different markets for some odd reason. It’s their child after all, and which parent wouldn’t? Another way to look at the export competitiveness of anything from Pakistan’s manufacturing sector would be to look at the United Nations Industrial Development Organization’s Competitive Industrial Performance Index.

The Competitive Industrial Performance Index benchmarks the ability of countries to produce and export manufactured goods competitively. It provides a graphical summary capturing the competitive performance of each of the 154 countries included in the 2020 CIP Index, relative to their performance in previous years and compared to that of the rest of the world. Pakistan ranks the worst across all of the aforementioned countries. It secured the 81st position in 2020, the last time the index was calculated, in comparison to India being 40th, Indonesia being 39th, Thailand being 25th, Malaysia being 21st, South Korea being 5th, and China being 2nd on the list. Pakistan’s also actually gotten worse over the years.

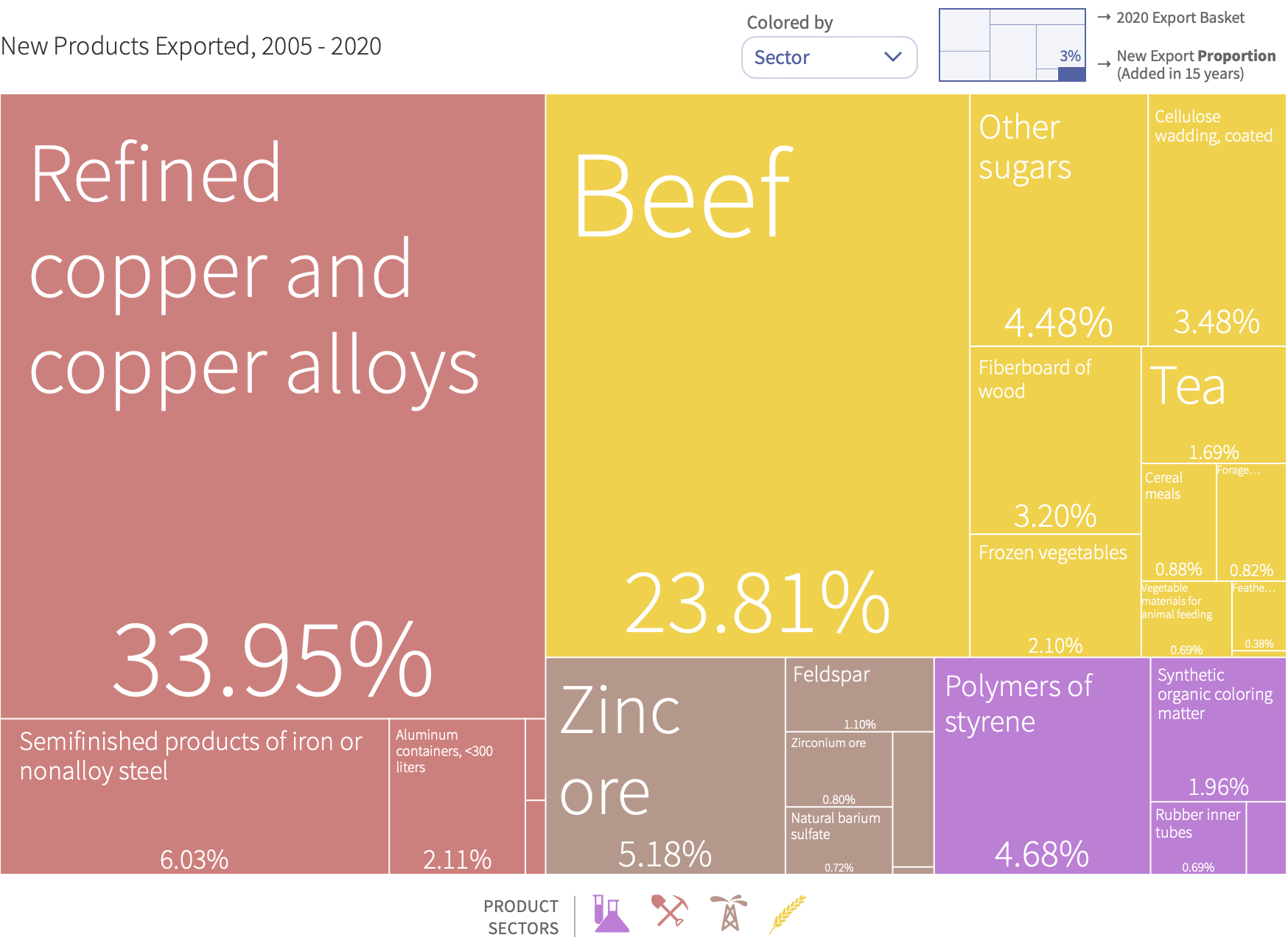

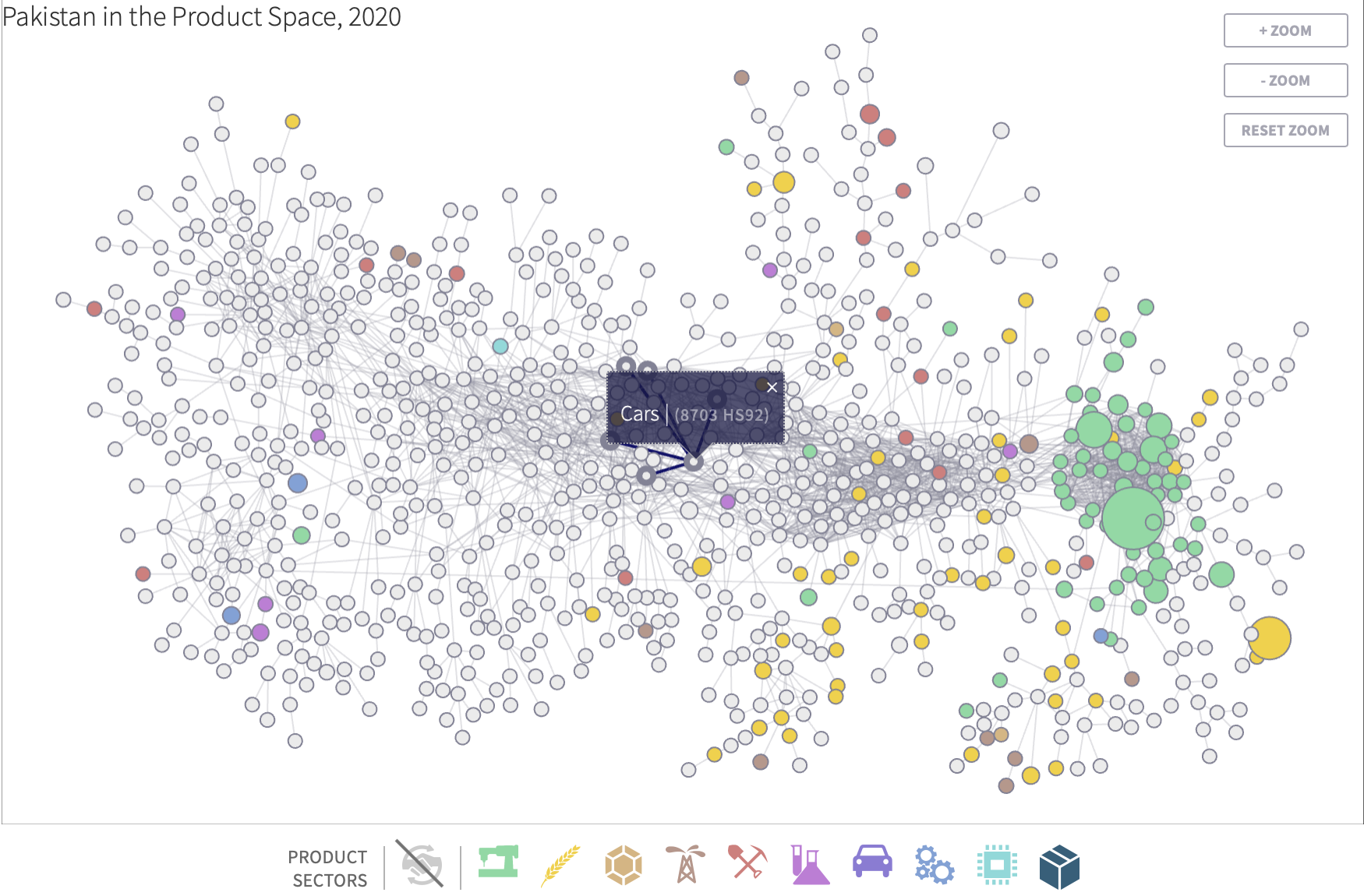

Furthermore, looking at Harvard’s Atlas Complexity, the new products that Pakistan has added to its export basket from 2005 to 2020 have nothing to do with the automotive sector to begin with.

Furthermore, looking at Harvard’s Atlas Complexity, the new products that Pakistan has added to its export basket from 2005 to 2020 have nothing to do with the automotive sector to begin with.

The new products that Pakistan has added are attributable to the chemicals, metals, minerals, and agricultural sectors. You could jump to the conclusion that these sectors are ancillary to the automotive industry. However, that would be incorrect. The Atlas includes the automotive sector, and subsequently encompasses any and all products even remotely associated with the sector.

What does this mean then? It means Pakistan not only has made ANY progress in the aforementioned fifteen years towards exporting anything from the automotive industry in any meaningful manner. But, its ability to do so relative to the rest of the world has actually diminished over time as well.

Put simply, if we can see those social media posts that indicate the world has better cars than we do then so can the world. Why would the world want to buy something from us that we would ideally like to not buy? But this is not a secret to anyone. The Auto Industry Development and Export Policy (AIDEP 2021-26) sought to fix this exact problem.

AIDEP sought to expand domestic capacity to 600,000 passenger vehicles, putting us right above Malaysia. Until it didn’t.

It’s the economy, stupid

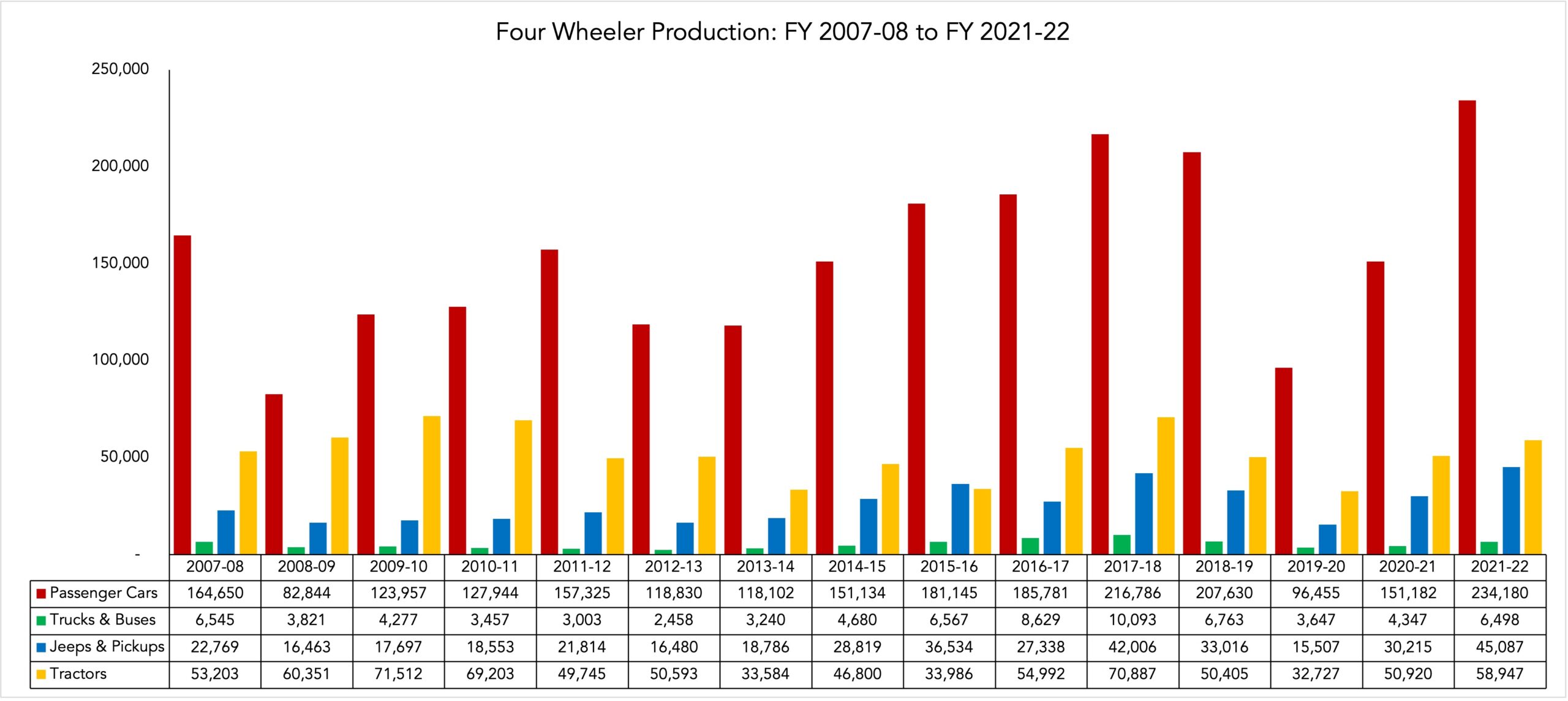

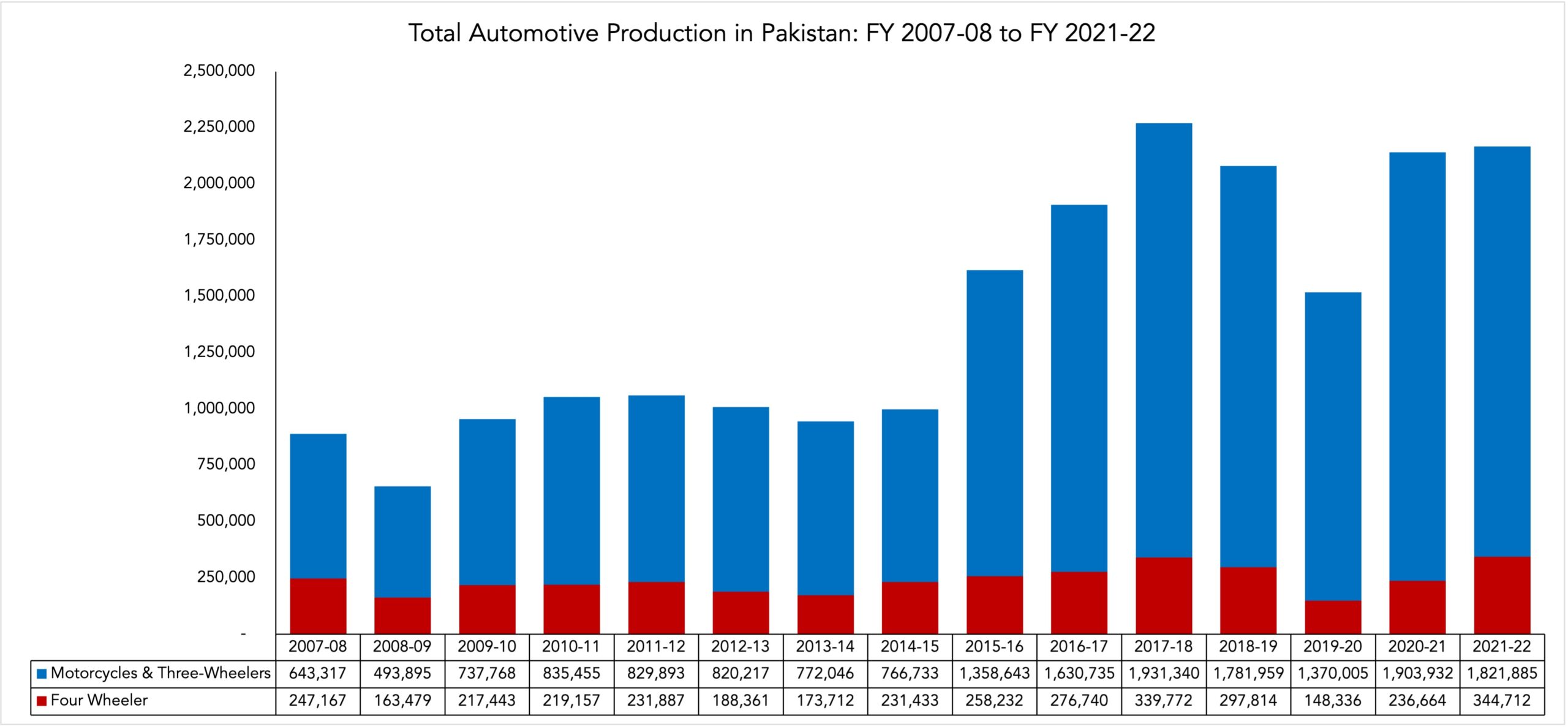

The Pakistan Automotive Manufacturers Association (PAMA) figures reveal that the domestic Pakistani market for automobiles has actually grown over the past years. Total automotive production has increased at a compound annualised growth rate of 6.56% between FY 2007-8 and FY 2021-22 which saw total automotive production in Pakistan increase from 890,484 units to 2,166,597 units.

However, this is perhaps as good as it gets for a while to come. Why do we say this? Because FY 2021-22 levels alone were enough to bleed so much foreign exchange that the State Bank had to step in and put a halt to the industry entirely. Profit has already documented this matter in detail for those interested.

Read more: The SBP is controlling car imports

The tl;dr edition, and what’s relevant to us is that Pakistani companies rely HEAVILY on imported components in manufacturing cars. Now that too is fine, it’s normal for any industry that’s part of the global value chain. The only problem is that ours is in a state of perpetual limbo. It uses imported inputs for products that are not exported in the end. Our existing export volume of other goods also, evidently, cannot sustain this production method.

Before the bad news, how about some good news? Pakistan’s current balance of payment crisis is largely in part due to the rise in the global price of oil. Furthermore, all the new automotive companies that pushed up imports did so because they are still new and lack the local supply chains that the Big 3 of Toyota, Honda, and Suzuki enjoy. The more they age, the more they will hopefully localise and thus not rely on imports. Theoretically, FY 2021-22 volumes can be beat.

Now the bad news. Those volumes are unlikely to be outdone exponentially. If for nothing else then because automotive companies’ localisation numbers are as good as monopoly money when it comes to actually fixing Pakistan’s economy. Profit has documented this too in detail.

Read more: How does Pakistan’s auto industry contribute to its balance of payment crisis?

More importantly than the problem with our deletion numbers is the actual process of achieving that deletion. This is where we go back to Hasanain’s last point: Upstream industries. Profit will actually expand upon his point by including ancillary industries that can support this endeavour. Why are we being liberal with his point? Just so that we can tell you how bleak the situation actually is.

One way to determine Pakistan’s ability to manufacture cars and look at the ancillary industries is by looking at the Atlas of Economic Complexity by Harvard University, again. It would be useful to actually explain it this time around.

The Atlas looks at a country’s economic complexity to determine its aptitude to produce other goods and services. Economic complexity of a country is calculated based on the diversity of exports a country produces and their ubiquity, or the number of the countries able to produce them (and those countries’ complexity).

Looking at Pakistan’s product space on the Atlas shows that it has no ancillary industries that can support large scale car manufacturing. Cars, in fact, are actually completely divorced from the entirety of Pakistan’s existing industrial base. Furthermore, the Atlas also determines how easy it would be for Pakistan to undertake the task of manufacturing automotives based on its existing base as well. So, how easy is it? Well, not at all actually.

The Atlas looks at the top 50 products that any country can ideally make based on their existing capabilities. Parts of motor vehicles rank at the very bottom at number 50 with motorcycles ranking at number 44. All other motor vehicle categories are not even on the list. Make what you must of that.

In essence it’s like a game of jenga. You need to have a base upon which you can add your fancy new Sino-Franco-Japanese-Korean car pieces.

So let’s catch-up. The automotive industry is an expensive business, and adding the latest features to a car is also very expensive. Companies keep their costs per feature they add by spreading it out over a greater number of units produced. Pakistan does not have a large enough domestic customer base which makes our companies inefficient, but they are also so inefficient that they can’t actually export the cars. AIDEP sought to increase Pakistan’s export competitiveness by creating a greater domestic market to facilitate economies of scale. However, Pakistan does not have the supporting industries to undertake this task which in turn led to the economy overheating, and forcing the Government to cut the sector down to size. This is a roundabout, really. No pun intended.

Continuing with our jenga reference, Profit would like to add the final piece because we, unlike the automotive sector, built a proper puzzle. The automotive companies, likely, do not care if anyone knows this.

The accidental autarky

The easiest solution to anyone wanting to rid themself of the ghum associated with those posts is to import the new Sportage rather than wait for it to be made locally at this point. However, the duties would probably make you want to buy a Fortuner instead. This is not accidental. If there’s anything the government loves more than curbing the local automotive industry to stem the flow of foreign exchange then it’s stemming the imported automotive industry.

“We have a lot of these assembly sites that have been set up around the country and they have been given incentives to do that. One major incentive that they are given is high tariffs. The high tariffs gives them the incentive to jump tariffs, come to Pakistan, invest in it, and avoid these tariffs,” explains Dr. Aadil Nakhoda, Assistant Professor at IBA.

Why is protectionism the route which Pakistan uses to attract companies? Well, that is another debate entirely. It is also beyond the scope of this article. However, this is the system that we do have, and the local companies are fully cognisant of this. This is why they are more likely than not to charge you that 15% GPM we talked about. This is also where the notion of tax and duties is negated, somewhat at least. “The tax and duties that can be passed on depend on the relative elasticities of supply and demand. They can pass on these as the demand is inelastic because there are no outside options,” Hasanain tells Profit.

“What is the threat that Toyota, and its peers face? Second-hand automotives from Japan. So think about this, manufacturers in Pakistan are worried about competition from four year old second-hand cars that come into the Pakistani market,” says Nakhoda. If you look at it like that, our cars are not quite bad when compared to four year old cars made for the Japanese market. And that is exactly the satisficing our companies need to do to continue their revenue streams.

In case you are in disbelief then let us convince you otherwise. The thing with tariffs is that there are two kinds of them: direct and indirect. Direct tariffs are additional levies on anything. They’re rather simple and are generally defined by automotive experts as brute force measures to mitigate imports. Indirect tariffs, however, come in different shapes and forms. One manifestation of indirect tariffs is technical non-tariff barriers.

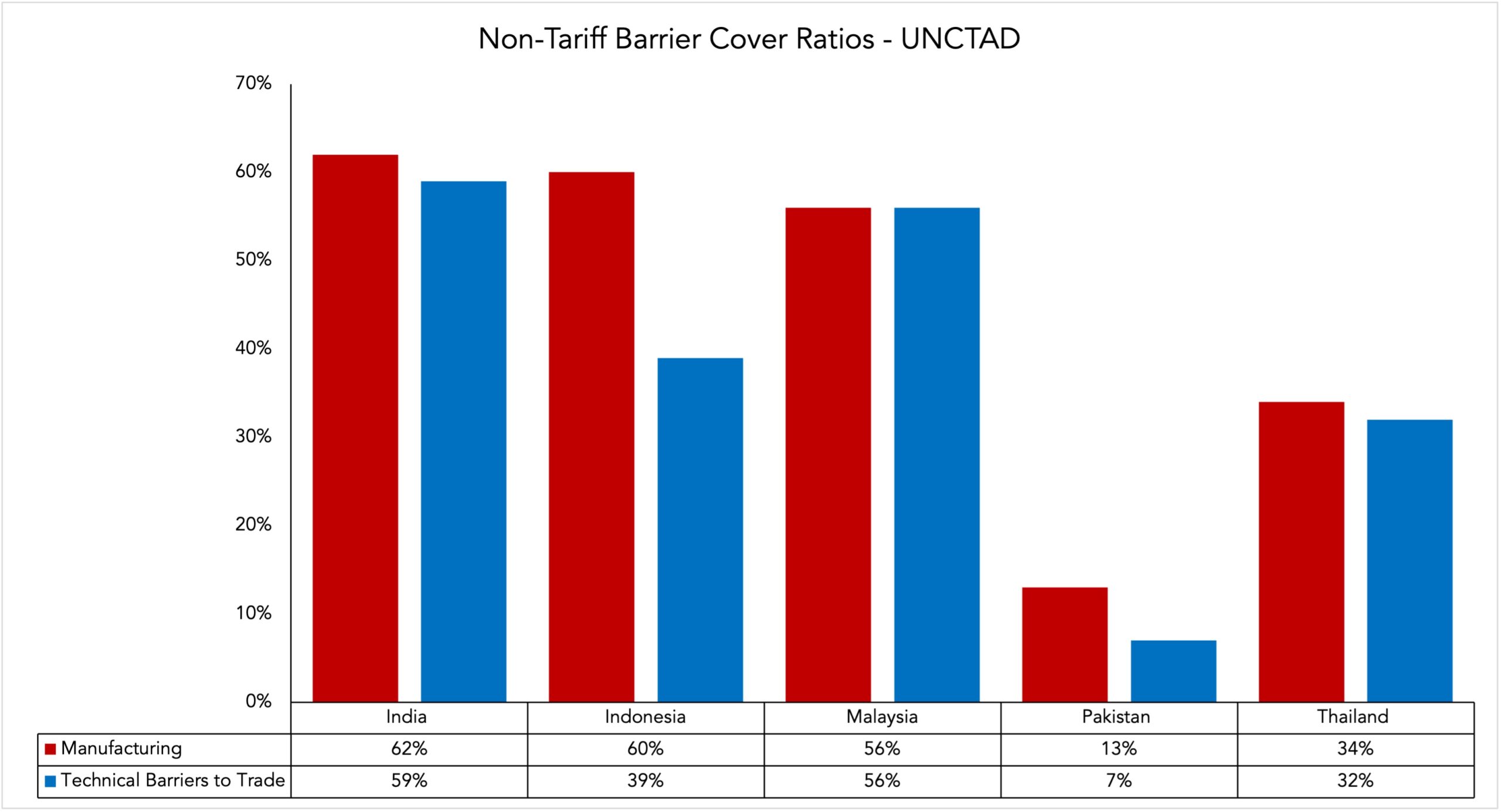

Looking at non-tariff barrier data provided by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, it is evident to see that Pakistan really doesn’t care much about why it’s stopping imports and rather just wants to stop them. The country ranked the lowest, amongst the aforementioned identified countries, in terms of cover for both its manufacturing industry and in terms of technical barriers to trade.

The former indicates that Pakistan’s only policy, relative to the identified peers, towards utilising tariffs in the manufacturing sector is to just price out imported substitutes. Similarly, the latter indicates that Pakistan does not really care about the quality of inputs that are imported into the country. Again, as with the former, the latter indicates the only aim is to price out foreign substitutes.

“We’re not protecting our industry technical measures, we’re utilising tariffs for protectionism. What that basically means is that we don’t care about the quality of the cars that are running in Pakistan. If we don’t apply these to imports then we really don’t care about what’s going to happen in the local production processes,” says Nakhoda.

“Mansha Sb, Taba Sb, Sherazi Sb, Habib Sb, and the rest are good people. They are honourable people. None of them are tax thieves. They pay their taxes and truthfully conduct their businesses. They are not thieves nor are they anti-Pakistan. However, everyone reacts to their policy incentives. If you have issues with car companies then you should address the laws and regulations so that their incentives are corrected,” Dr. Miftah Ismail, former Finance Minister of Pakistan and one of the Architects of the 2016-21 Auto Policy, tells Profit when asked if the companies were gaming the system.

You can’t decouple the micro from the macro

Not having auto-dimming mirrors is a travesty for anyone that’s driven ahead of a Honda Civic on the streets of Lahore. However, we’ve outlined why they’re unlikely to become standardised anytime soon. The question then is what would it take?

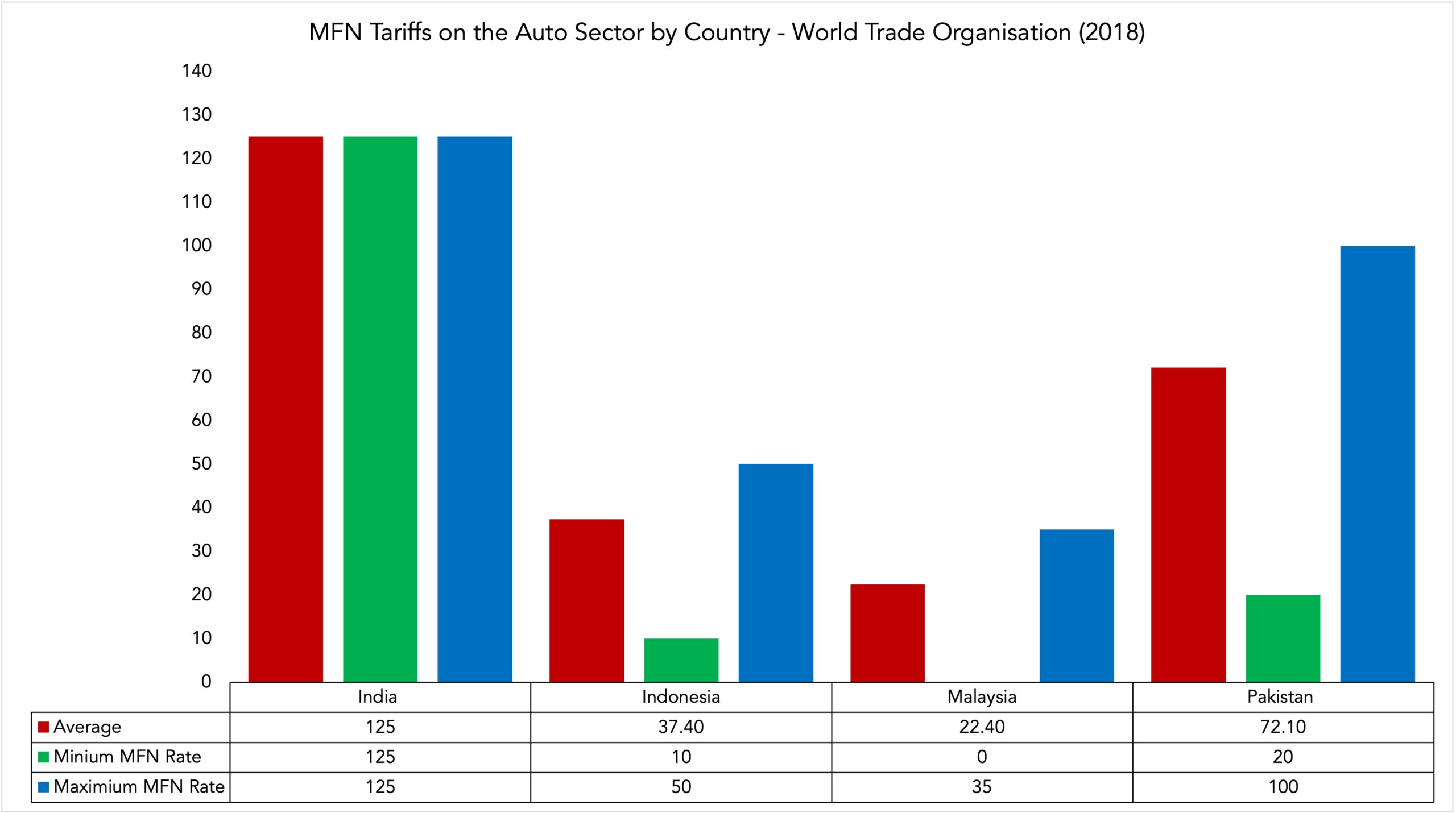

The easy answer would be to simply have a proper functioning economy, liberalise trade, and just import whatever car you want. However, at this point you are more likely to win the lottery than to be able to convince any Pakistani government to undertake this task successfully. Tariffs aren’t all bad. “Does Thailand not have tariff protection? Does India not have it? Does Malaysia not have it? They have also protected their sectors. They are perfectly intelligent countries so what is the harm in copying them? Our sector is less protected than theirs,” says Ayaz.

Looking at the tariff data provided by the World Trade Organisation, Pakistan’s automotive sector is less protected than India’s based on most favoured nation (MFN) tariffs, and is actually comparable to Indonesia. MFN tariffs are the highest rates that countries can impose on trading partners that are members of the WTO. Comparison with other aforementioned countries could not be conducted because of the mismatch in data available, as Pakistan’s does not exceed 2018 and the others do not provide data as far back as 2018.

The aim should be to try to find a solution utilised by Thailand and Mexico, for example, and find a way to integrate into global value chains to achieve the desired capacity rather than continue down the India and China route. Unless, of course we find a way to fix the aforementioned issues highlighted that hinder us from emulating India and China. Creative solutions are of the utmost importance.

“If you were to suddenly open imports then all the new companies that did invest in Pakistan would suffer a huge loss. The solution to that is, unfortunately nothing in Pakistan happens like this and this is unlikely as well, you formulate a plan to pivot all those companies. You tell them that they can make as much money as you want for the next four to five years to recover your investments. However, you tell them that you will taper off protectionism in the coming years, and eventually you will completely open the automotive market to imports in the tenth year,” explains Hasanain.

Is this a viable solution? Perhaps. “If you had used the word shampoo instead of car then it would have still been valid. We have protected the local shampoo industry as well, just maybe not as much. We have provided protectionism to every sector,” states Ismail.

“The notions on which our edifice of import substitutions were built are long standing. You cannot remove it immediately. If you want to manufacture a car in Pakistan and also levy duties on its imports then the current situation is a given. In my opinion, everyone stuck in this mess is stuck,” Ismail continues.

As much as Profit would like to tell you there’s hope, but there isn’t much to be honest. You may ask why we make cars at all to begin with then? That is a debate for another time, however, it is one that will pester us because the solution to getting as many airbags in all our cars as the ones in India is not one that will come anytime soon. Rest assured that social media will continue to bombard us all with those posts about how much better cars are the world over in the meantime.

Good post! We will be linking to this particularly great post on our site. Keep up the great writing

And where is that answer?

Explain best car industry in Pakistan and their policies. Very Well done

I don’t Know about car but new revolutuons is Revolt Bikes: You Can Check revoltmotors.org it’s AI Based Mototor Bikes without using petrol and disel.

It’s very good. Thank you. It’s easy to understand, easy to read, and very knowledgeable.

온라인 카지노

j9korea.com

Irony is that the same outfit (Profit) profits out of the ad campaigns by these s..t makers, proudly, believe me😂