This year’s budget was presented under tense circumstances. With an IMF deal still not secured and political turmoil reaching a boiling point there was little on anybody’s mind except what measures the budget would impose and whether it would manage to steer Pakistan away from default.

Yet outside of this immediate concern, one of the most prevalent conversations taking place at the Prime Minister’s office and within cabinet was the question of the country’s agriculture. As an agrarian economy, Pakistan has long relied on the fact that it is capable of producing enough food to fulfil the caloric requirements of its own population, and then have enough leftover to be an exporter.

Historically this has been true. It also means that no matter what happens, the country’s population can reasonably be fed and taken care of without any reliance on imports — at least that is theoretically correct. Over the past few years, the country has emerged as a net importer of food.

Which is why in a major huddle before the budget that took place on the 1st of June, the prime minister vowed to give priority to the agriculture sector by offering incentives to growers to improve production and rural economy. The talking points were the same as always — better subsidies, better support prices, and more assistance from the government.

That, of course, is well and good. However, subsidies and support prices are short term solutions that temporarily boost agriculture in the country. These are the same solutions and promises that have been made before earlier budgets too.

That, of course, is well and good. However, subsidies and support prices are short term solutions that temporarily boost agriculture in the country. These are the same solutions and promises that have been made before earlier budgets too.

The reality is that agriculture is the largest real sector of the economy and one of our most major products. A concentrated effort is required to make it bigger, better, more profitable, and export oriented. So what does this year’s budget look like for the agriculture sector? In short it looks like things will stay much as they have in years past.

The depth of the problem

Food security is possibly one of the biggest problems facing Pakistan right now. In an international ranking of the Global Hunger Index (GHI) this year, the country ranked 92 out of 116 nations, with its hunger categorised as ‘serious.’ Pakistan currently faces a scenario in which it is largely food sufficient but not food secure.

Despite Pakistan being ranked 8th in producing wheat, 10th in rice, 5th in sugarcane, and 4th in milk production, a 2019 report of the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) showed that nearly 37% of households in Pakistan are food insecure. In the four years since the SBP’s report, matters have only worsened. Food price inflation in Pakistan has been in double digits since August 2019. The cost of food has been 10.4-19.5% higher than the previous year in urban areas and 12.6-23.8% in rural areas, according to figures published by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the concept of food security is flexible, but is widely believed to “exist when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food which meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.”

In short, for a country to be considered food sufficient it does not just have to produce a sufficient amount of food, but that food should be easily available, affordable, and of a quality that meets basic nutritional requirements. For a reliable level of food security, it is vital that the access and affordability of food is not affected by shock events such as floods and economic crises that result in inflation.

The concept is not difficult to grasp, but it is so simple that it often gets lost in the cracks. Food is the most basic building block of human life. The quality and quantity of caloric intake of a population affects its overall productivity, standard of living, and most importantly happiness and satisfaction.

While access to food is a basic, fundamental human right there is a way to put an economic cost on food insecurity. The lack of food security has strong economic implications. According to a special section of the SBP’s annual report from 2019-20, the state of food security has strong linkages with the state of human capital in the country. The Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations has also estimated that a high rate of malnutrition can cost an economy around 3-4% of GDP. In the case of Pakistan, estimates suggest that malnutrition and its outcomes cost the economy 3% of GDP (US$ 7.6 billion) every year.

To put this in very mathematical terms, malnutrition and food insecurity manifests in the shape of high child mortality rates, prevalence of zinc and iodine deficiencies, stunting, and anaemia, which lead to deficits in physical and mental development that weakens labour productivity and loss of future labour force in the country.

On a much more human level, however, the lack of food security means a whole lot of misery, hunger, and anguish. According to the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report for 2020, prevalence of undernourishment in Pakistan is 12.3% and an estimated 26 million people in Pakistan are undernourished or food-insecure. Pakistan’s children have suffered and are continuing to suffer. Malnutrition from an early age results in consequences that last entire lifetimes.

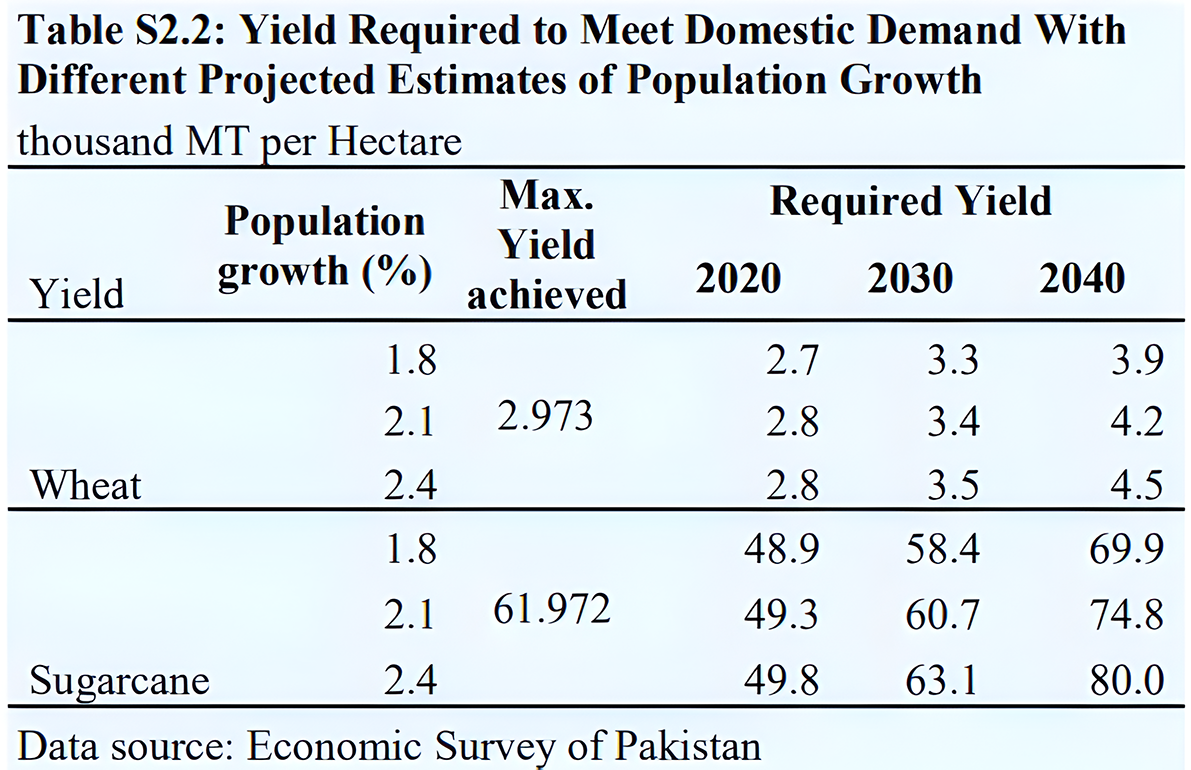

Add on top of that a high population growth and unfavourable water and climatic conditions and you have a scenario that threatens to spill over and cause mayhem. Pakistan is barely maintaining its current food security level of just over 60%. According to the SBP report mentioned earlier, “of the 36.9 percent of the households in Pakistan labelled as “food insecure”, 18.3 percent face “severe” food insecurity.” Concerns over food security may increase at an alarming rate over the next two or three decades. This will also mean that the overall fiscal and balance-of-payments cost will also escalate just to maintain the current level of food security in the country.

The deep rooted causes

There are of course reasons behind this. So how does a country with one of the largest agrarian economies in the world find itself unable to sufficiently provide food for nearly 40% of its population? For decades, agriculture has been neglected and people’s earnings have been hit by one economic crisis after another. On top of this, particularly in the past decade or so, climate change related disasters and changes in the environment have resulted in our already neglected agriculture becoming less competitive.

One of the most important things to understand is that as the world’s population has grown, more land has had to be brought under cultivation to meet humanity’s caloric needs. And as the world has progressed, this has required a serious scientific approach. Research in the field of agriculture has led to mechanisation of farms, the development of seeds that give higher yields and are more resistant to different weather conditions, and areas before thought uncultivable have been turned into rich sources of food. The primary role of agricultural research is to heighten knowledge and improve technology. It heightens understanding of the interactions and interdependence between production systems and farming communities. This requires a holistic and interdisciplinary approach to problem identification, analysis and solution-finding.

This has been entirely missing in Pakistan. A major reason for the food price inflation in recent times are increasing input costs for agriculture over the past two years. Higher fuel prices and the devaluation of the rupee have led to a rise in costs in both fertiliser and seeds. Prices increase more in rural areas because commodities are diverted to cities due to higher profit margins, and because of the higher cost of imported items such as pulses and cooking oil.

On top of this, land is disproportionately owned in the country. This has led to a vast misutilization of the subsidies and support prices that the government very regularly offers. On top of this, the effects of climate change have been devastatingly clear.

According to UNESCAP, Pakistan could lose more than 9% of its annual GDP due to climate change. Severe heat waves and untimely rains have also severely impacted Pakistan’s agricultural production. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has warned that the frequency of such extreme weather conditions will increase in the future, causing a severe risk to Pakistan’s food security. The Asian Development Bank projects sharp declines in key food and cash crops (such as wheat, sugarcane, rice, maize, and cotton) in the coming years due to rising cultivating costs and climate change.

So what does this year’s budget have to offer?

The 2023-24 budget really doesn’t do much to solve any of these deep rooted issues. The federal government has allocated Rs21 billion in the budget for 2022-23 under a three-year Growth Strategy for improving the output of crops and livestock, countering climate change impact, promoting smart agriculture, value-addition and agro-processing. It has also announced Rs11bn for the provision of the latest machinery, laser land-levellers and quality seeds for the agriculture sector and enhancing exports of farm produce.

In terms of relief, the government has abolished sales tax on tractors, other agriculture tools as well as seeds and has made customs duty zero on import of agricultural tools, irrigation systems, harvesting machines, greenhouse farming and for agro-based industries.

It has increased subsidies for fertiliser plants from Rs6bn in the outgoing year to Rs15bn for the year 2022-23, a 150pc hike. A separate allocation of Rs6.0bn has been made as a subsidy for urea compost import. The government has apportioned Rs10bn for agriculture relief initiatives without giving any details in the budget documents.

Among the steps announced by Finance Minister Ishaq Dar on Friday is a significantly large increase in loans for farmers — from Rs1.8tr Rs2.2tr — the allocation of Rs50bn to shift 50,000 tube wells to solar power, the withdrawal of duties on seed import, and duty exemption on the import of combine harvesters.

The talking points have all been the same as well. The government promised to ensure direct provision of subsidy to farmers on fertilisers, timely loans, and direct support prices. However, the measures must go beyond years. Last year when the prime minister had just come into power, his response to the catastrophic floods in the country had been announcing the Kissan Subsidy Package.

Under the package, the government will give Rs10.6 billion loans to small farmers across the country while small farmers of flood-hit areas would get loans worth Rs 80 billion. In addition to the interest-free and subsidised loans, subsidies will also be given on farm imports such as fertilisers, electricity, seeds, and even tractors.

This was necessary in the face of devastation. If implemented correctly, packages such as this have a wide-reaching impact in helping farmers affected by this year’s floods back on their feet. But that is as far as they can and should go. The scale of the problem faced by our agricultural sector will not be fixed by any subsidy package. At most, any subsidy will provide temporary relief. For too long the state has allowed the country’s agriculture to suffer and have offered only stop-gap solutions such as subsidy packaged. We have been papering over the cracks for so long that our entire agrarian economy has grown dependent on subsidy packages.

For decades Pakistan has been falling behind on agricultural competitiveness. While the rest of the world has developed through research, mechanisation, and technological advancements we have lagged behind. On top of that now our farmers are facing the harsh and unpredictable realities of climate change.

Pakistan’s own neighbours like China and India have managed to specialise in certain crops and become the leading producers of those crops in the entire world. Meanwhile Pakistan has lost its edge in the global markets. Simply take a look at our cotton production as an example. Between 2015 and 2020, Pakistan’s production of cotton declined by nearly 35%, from nearly 14 million bales in 2015 to just over 9 million bales in 2020.

And while our cotton production and quality have gone down, countries like Egypt have used the latest genetically modified seeds to get more yield per area with better quality fibres as well. At the same time, they have also industrialised and set-up the processing of these crops domestically. With no focus on value-addition or research, Pakistan’s agriculture is down and out for the count on many fronts. For almost all of our major produce, we have low crop yields, soil infertility, outdated farm practices, and extremely low mechanisation. Already dogged by these problems, our beleaguered farmers now face a serious threat from climate change as well. Weather patterns are wild and erratic, going from drought to flood within a matter of months.

If Pakistan is to move forward on the agricultural front, which it must if it wants to maintain food security, we will have to shift our focus from subsidies to actual research and development. Agriculture is still the largest component of our economy, and fixing it will take persistent, daily, dedicated, single-minded focus. It is the need of the hour, and with the effects of climate change knocking on our doors there has never been a more urgent moment in time to try and fix it.