The most powerful people in Pakistan were all at the Serena Hotel in Islamabad this week to mark the first Pakistan Mineral Summit. The country’s top political and military leadership along with scientists, experts, and industry high-ups were present to discuss the country’s potential as a hub for mining and natural resources.

The theme of the event seemed to be hope. The claim was that with its vast and unexplored natural resources Pakistan could possibly be home to over $6 trillion worth of natural resources. In the face of this very hopeful and very generous estimate those at the conference gave the impression of a tightly sealed united front.

The minerals summit titled “Dust to Development: Investment Opportunities in Pakistan” was a joint effort by Pakistan’s Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC) and Canada-based Barrick Gold Corporation, facilitated by Pakistan’s Ministry of Petroleum. Pakistan’s Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif and Pakistan Army Chief General Syed Asim Munir addressed the keynote sessions at the summit.

The event was bolstered in particular by a high-profile delegation from Saudi Arabia which arrived in Pakistan to participate in the inaugural summit. Led by Saudi Vice Minister for Mining Affairs, Engineer Khalid bin Saleh Al Mudaifer, the delegation also included representatives from Saudi mining companies Ma’aden and Manara Minerals. Saudi Arabia is currently the world’s fourth-largest net importer of mineral products.

In the midst of these tall claims it is important to remember something — the $6 trillion figure is not just an estimation but one that is on the more generous end. In reality, with projects and initiatives like this, the full potential is rarely unlocked and even what is usually there takes decades upon decades to explore and mine. But putting that aside the reality is that Pakistan does indeed have vast natural resource potential. The question is, can we harvest it? In the past there have been some successes and other times when literally golden opportunities were embarrassingly fumbled.

Perhaps because of this one of the most interesting speeches at the conference was developed by the CEO of Engro, Mr Ghias Khan, who pointed towards the need for public-private partnership to make such chances count. More than anyone else, Engro and its CEO are in a place to comment on this because they have been at the center of one of the biggest natural resource related successes Pakistan has seen — Thar Coal.

“Thar produces 10% of PK’s power & saves $1bn in imports/yr. Its socio-economic success provides a blueprint of how to unlock Pakistan’s $6 trillion mining potential,” Ghias said in a tweet following the event. “What would be really good to see is the presence of the Pakistani private sector in mineral mining as well because, with the stewardship of the federal and provincial government, it was the private sector that led Thar’s development. The Thar example gives us this blueprint which is namely:

- The power of public-private partnership models

- Patient capital with a long-view is essential

- Projects of national interest should transcend politics

- Private sector involvement is key to mineral mining success and development of local regions. These are the kinds of projects that can change the fate of nations.

Thar coal is indeed a good, home-grown example of managing and profiting from natural resources. Then again, Pakistan also has a glaring example of how not to manage its natural resources — Reko Diq. With the discovery of new natural resources and mineral reserves Pakistan is poised to possibly change its destiny. Foreign investors will be interested and while it might not be worth $6 trillion Pakistan can make this a major source of exports and income. We must focus on learning from both our mistakes and our successes to take full advantage of whatever potential Pakistan possesses.

The Thar Coal example

It is a simple problem. Pakistan relies heavily on imported fuel sources such as reliquified natural gas (RLNG) to produce electricity. Whenever there is an international crisis, such as the Russia-Ukraine war, Pakistan’s energy sector is rocked by the ripple effect. There is a simple solution. Cheaper fuel — something like coal perhaps. And the source is right there too. Spread over more than 9000 km2, the Thar coal fields are one of the largest deposits of lignite coal in the world — with an estimated 175 billion tonnes of coal that according to some could solve Pakistan’s energy woes for, not decades, but centuries to come.

The question is, if this rich natural resource is available, why has it not been utilised more than it is currently? Discovered in the early 1990s by the Geological Survey of Pakistan (GSP), Thar Coal accounts for around 2000 MW of electricity produced in the country — a number that has risen from 660 MW just one year ago.

In short, Thar Coal offers a cheap, alternative, local source of energy that can be used to produce electricity and help Pakistan escape its topsy-turvy reliance on international markets to maintain its energy supply.

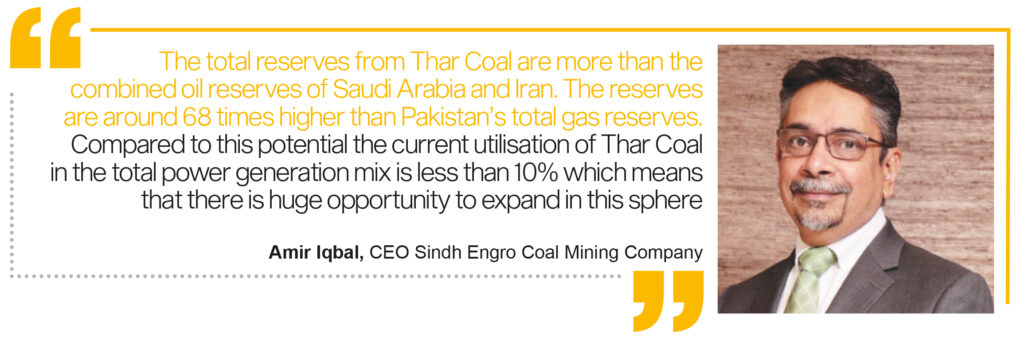

“The total reserves from Thar Coal are more than the combined oil reserves of Saudi Arabia and Iran. The reserves are around 68 times higher than Pakistan’s total gas reserves. Compared to this potential the current utilisation of Thar Coal in the total power generation mix is less than 10% which means that there is huge opportunity to expand in this sphere,” said Amir Iqbal, CEO of Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company, in an earlier interview with Profit. “That means Thar Coal has the potential to produce approximately 100,000 megawatts of electricity for 200 years – enough to make Pakistan self-sufficient in the energy sector.”

“The recent global supply chain disruptions have brought to light how Pakistan’s reliance on imported fuels is detrimental to its long-term economic growth,” says Engro Mining boss Amir Iqbal. “The country’s energy mix needs an urgent overhaul with more indigenous sources like Thar Coal added to it. This will save precious foreign exchange reserves and put Pakistan on the path of sustainable energy security.”

“This is one of the major advantages of using Thar Coal, as it is the most economically viable source of fuel for the country. Thar coal expansion could also provide a huge relief for FOREX reserves of Pakistan with savings of approximately USD 2.5 billion, while it will result in the reduction of more than PKR 100 billion in circular debt on an annual basis.”

Already, Thar Coal is being touted as the solution to many of Karachi’s electricity woes as well. The new owners of K-Electric have said an investment of $3.5 billion will be made in the next five years for cheap electricity. This investment will encompass wind, coal, and solar energy projects to ensure affordable electricity for the citizens of Karachi. In the first phase, the power plant located in Jamshoro will be shifted from imported coal to Thar coal as the production at Jamshoro Coal Power Plant has been shut down due to non availability of imported coal.

As of now, other than Engro’s plant, all coal power plants in the country are reliant on imported coal. Using Thar coal would mean Pakistan could indigenously produce electricity. All of this has only been possible because on this occasion, Thar coal has not faced undue red-taping or court involvements. A big part of this is because Thar Coal was part of an early harvest CPEC project and thus the government was on its best behaviour. In actuality the government of Pakistan is not always the most reliable business partner — something that was clearly on display in our other example: Reko Diq.

The Reko Diq debacle

Reko Diq, which means sandy peak in Balochi, is a small town in district Chagai, Balochistan. Geological literature reveals that the Chagai district is part of a belt called the Tethyan Magmatic Arc, which stretches from Turkey and Iran into Pakistan. The arc is a known reservoir for rare earth metals, and Pakistan’s share lies underneath the region between Chagai and North Waziristan. Reko Diq is said to hold an estimated 5.9 billion tons of mineral resources, with an average copper grade of 0.41 percent and gold grade of 0.22 grams per ton.

Out of a total 5.9 billion tons of ore, only 2.2 billion tons are economically extractable. The total area of the Reko Diq mines is said to be spread over 13,000 square kilometres. With such figures, it is believed to hold the world’s fifth largest deposits of copper and gold. The resources were originally explored in 1993 by an Australian company, BHP Billiton, after signing an agreement with Balochistan’s then caretaker government under the leadership of chief minister Naseer Mengal.

To put it very briefly it was a golden opportunity. But over the next two decades the exploration of Reko Diq kept changing hands. This was the first bad sign. In April 2000, BHP suspended its exploratory work and handed over its obligations to another Australian company, Mincor Resources. In 2006, Mincor was acquired by the TCC which is a subsidiary of Mincor and a joint venture between Canadian-Israeli owned Barrick Gold and Antofagasta of Chile. In the same year, the legality of CHEJVA was challenged in the Balochistan High Court.

Throughout this process the government did not resist these transfers — something perceived to have been because of inefficiency. On top of this, different cases were filed in both provincial and federal courts over the matter. Very briefly put the entire matter became a legal quagmire that nobody wanted to touch.

In 2012, the TCC took the matter to the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) to seek compensation for $11.43bn in damages after the Balochistan government turned down a leasing request from the company. In July 2017, the ICSID ruled against Pakistan by declaring that there was no wrongdoing in CHEJVA – the ground on which the Supreme Court of Pakistan had terminated the agreement. Eventually the tribunal held that Pakistan was liable to pay damages.

This had Pakistan in a complete bind. By 2022, some of these matters had settled. In fact, after receiving a favourable ruling from the Supreme Court of Pakistan, Barrick Gold even announced its intentions to reconstitute work on the site.

Using the figures provided by Arif Habib Limited report “Revival of Reko Diq Project”, the scope and earnings this project would generate are massive to say the least. The project is divided into two phases, with a total projected capex cost of $7 billion, with the first phase requiring $4 billion and the second phase requiring $3 billion. In addition, the project’s total entry amount is $2.2 billion, bringing the entire project size to $9-10 billion. Annual copper output is predicted to be between 650 and 700 million pounds per annum for the first ten years, increasing to 800 to 850 million pounds per annum when phase 2 is completed. Furthermore, gold production is estimated to be 300,000 to 350,000 ounces on yearly basis for the first ten years (first phase) before increasing to 450,000 to 500,000 oz. following the planned expansion.

To estimate the overall value of the project we’ll assume constant pricing for both gold and copper, taking the average price of the commodities over the period of the last ten years. If we were to only look at the first phase of the project, keeping in mind the numbers above, it would generate an estimated $ 14 billion for the government in only the first 10 years of its operation. The significant portion of the revenue would be dominated by the sale of Copper and would account for 83.25% or $11.67 billion of the revenue in the first phase, whereas Gold would account for the remaining 16.75% or $2.35 billion.

Likewise, with the expansion envisioned for the second phase the output of the mine would increase, and with it the revenues generated would also rise. An accumulative revenue amount of $62 billion is expected to be generated over the course of the second phase that has a stipulated time period of 35 years.

To sum it all up, the Government of Pakistan would be able to generate an average of $1.4 billion annually over the course of the first phase and an additional $1.7 billion over the next 35 years during the second phase of the project. This would amount to a whopping $76 billion over the next 45-50 years. Although these estimates and calculations provide a simplistic understanding of the monetary returns expected to be generated by Reko Diq, these are still estimates nonetheless. The considerations taken to keep the number crunching consistent do not account for the variable price of copper and gold in the international market as well as other direct and indirect factors.

The government is an unreliable partner

And this is also where the problem mostly exists. All of these projections are well and good. The fact of the matter is that the government of Pakistan first started its exploration of Reko Diq in the early 90s. It has been more than three decades since then.

The scale of such projects is not quite understood by most people. Even with Reko Diq, now that the dust has settled from more than 30 years of legal battles, there are countless problems that exist. A key concern that still requires attention is the logistical aspect of this mega project, considering the remoteness of the project site, and consequently the logistics required to make this a feasible project have to be further developed.

Taking the example of the Saindak silver mine located in Chaghai, the silver ore extracted from the mine has to be transported 1,127 km from the site to the port in Karachi by trucks. That is absolutely ridiculous, as the costs associated with using trucks would have an adverse effect on the bottom line and overall feasibility of the project. If a similar plan is on the table for Reko Diq, the margins of Barrick and the Government would significantly diminish.

Water was highlighted as the project’s “most critical” issue in the Risk Assessment Report pertaining to Reko Diq published by Behre Dolbear in October 2007, and Pakistan underlined it during the ICSID hearings whilst examining the feasibility of ensuring water supply. Water is most commonly used in mining to process ore and to water mine roads to reduce dust. Aquifers, surface water, collected precipitation, and even water from the mine itself, provided the mine is actively dewatered, are all possible sources of water for mining.

Naturally due to the remoteness of the site location, developing infrastructure and building a sustainable water source for the next 45 years for the mining operations is a monumental challenge.

And then there is the biggest challenge. Historically as Pakistanis all of us have been witness to unsuppressed corruption, inefficiencies as well as plain and simple stupidity on part of the decision makers and various government entities. The country has a chequered past of poorly executed projects and pitiful government oversight with next to little or no support to investors. To compound all this, bureaucrats and politicians in positions of power never fail to get their kickbacks from projects like these.

As things stand now, the country’s leadership seems united on the potential of mineral mining in Pakistan. During his address, Army Chief General Syed Asim Munir emphasised the importance of joint efforts to realise the country’s mineral potential. With abundant mining opportunities, he invited foreign investors to contribute to realising the potential of Pakistan’s estimated $6 trillion worth of natural deposits.

“Foreign investors will be an integral part of the mines and mineral projects” and their investment will be secure under the SIFC established in June this year to offer single-window operations to potential investors. Gen Munir promised an investor-friendly system, ensuring ease of doing business and minimising unnecessary delays.

Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif expressed optimism that initiatives like the SIFC could turn hope into reality, enabling Pakistan to make its mark in the global economy. He emphasised the importance of transforming the country’s fortunes and attracting international investors for economic prosperity and development.

“We need to build a stronger narrative for a better future and the mineral wealth of Pakistan is a great opportunity for us to make our mark in the global economy. SIFC is an excellent step that can help Pakistan optimise the opportunities for Foreign Direct Investment”, the prime minister said.

But even the most efficiently managed natural resources project can take years upon years to kick off and start paying off. In Pakistan’s case there is the added baggage of the government’s long history of being an unreliable business partner. In the case of Reko Diq, decades later we are now in a position to start. On the flip side, Thar Coal has proven to be a natural resources exploration project that has paid off.

Which route Pakistan takes for the future will determine a lot.