As you read this article, history is about to be made. Pakistan stands on the brink of a momentous occasion: the third consecutive democratic election in its tumultuous history.

It is a contentious election for many reasons. Not because it is particularly hotly contested but because there are more than the usual few aspersions on the integrity of the electoral process. And while political engineering and level playing fields are on everyone’s mind, most people might not realise there is an entire tier of democracy they are being deprived of in this election. It is not noticeable because this deprivation is nothing new.

Local governments simply do not exist in Pakistan. They are very much supposed to. When the 18th Amendment was passed in Pakistan in 2008, powers were stripped both from the President of Pakistan and the Federal Government. Some powers and responsibilities previously held by the centre were devolved to the provinces. These provinces were then further supposed to devolve powers to a third tier democracy: local governments.

The concept was simple. Before 2008, the federal government was responsible for everything from foreign policy to health and education. After the amendment, matters like health and education were given over to the provinces. This way, legislators in parliament would get time to focus their energy on the larger picture. Similarly, the provincial legislature is supposed to let local governments deal with issues such as taxation, and local water and sanitation issues.

The case for local governments is one that has been flogged to death, whilst local governments never draw a single breath. However, that does not diminish their significance. It may sound trite to say that they are more vital than ever now, but the case is especially compelling when any prospective government will need all hands on deck to tackle a relentless economic crisis on a war footing.

Local Governments 101

Local administrations represent the most fundamental tier of public governance within a state or district. In a multitude of nations, they embody the third tier of governance. This holds true for Pakistan as well, where local administrations are subordinate to both federal and provincial governments. The three varieties of local governments are: district government administrations, town (tehsil) municipal administrations, and union council administrations.

This publication has already covered the details of what a local government can, and cannot do previously.

Read more: The great local government gambit

Every tier boasts its own distinctive service functions and obligations. At tehsil level, the spotlight is on health, community development, education and agriculture. Infrastructure and municipal services are concentrated at the district level, whereas community services occur at union level. These three levels of local government are harmonised and consolidated with the aid of a bottom-up system, composed of clear-cut electoral arrangements, planning systems, and specific procedures for overseeing service delivery.

The history of these local governments have been exhaustively penned by myriad publications. Their existence predates the creation of Pakistan, functioning within the modern boundaries of Pakistan prior to its inception. At present, local governments are operational solely in Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Sindh. Of these, the one in Sindh is perhaps the most noteworthy, owing to the presence of Karachi. Consequently, we extended an invitation to the Mayor of Karachi — Murtaza Wahab. An interview was agreed upon in principle, yet it remains unrealised at the time of writing.

Has there been a local government system that historically towered above the rest?

“Although we harbour differences with Pervez Musharraf’s government, primarily due to the illegitimacy of his regime, one commendable act was the empowerment of local government. For the first time, we witnessed an effective local government,” asserts Ahmed Bilal Mehboob, the President of the Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency (PILDAT).

Firstly, Musharraf’s local government system was far from perfect. It was met with widespread disapproval. A survey conducted by Pattan, assessing the performance of district nazims (Mayor) from 2001 to 2006, revealed that over 50% of males and females were dissatisfied with their District Nazims by the end of their tenure. However, many nostalgically hark back to the Musharraf era local governments, viewing them as the closest Pakistan has come to a functioning system of this sort. Providentially, it is also the most extensively documented and will consequently serve as the cornerstone of this piece.

The service delivery question

It is a widely held belief that decentralisation enhances accountability, as voters can more effectively scrutinise the actions of policy-makers due to their relative closeness, and policy-makers, in turn, seeking re-election, are attentive to voter preferences. Given that the median voter in a developing country is impoverished, and that advancements in basic education, health and physical infrastructure services benefit the poor, this attentiveness leads to better service delivery.

This argument forms one of the key pillars that advocates of local governments lean on when extolling their numerous virtues.

“Development, while not exclusive to the presence of local government, tends to be executed with greater efficiency under its auspices. Projects are not only more abundant but also completed at a brisker pace, largely because those responsible for their execution are more directly accountable to the local populace,” contends Mehboob.

“I believe if you inquire with anyone in Karachi, they will recount how the most development transpired when powers were delegated to the local level in 2001,” Mehboob adds. Sadly, we cannot regale readers from Karachi with the nostalgia that Mehboob points towards. However, we did find the data for Punjab.

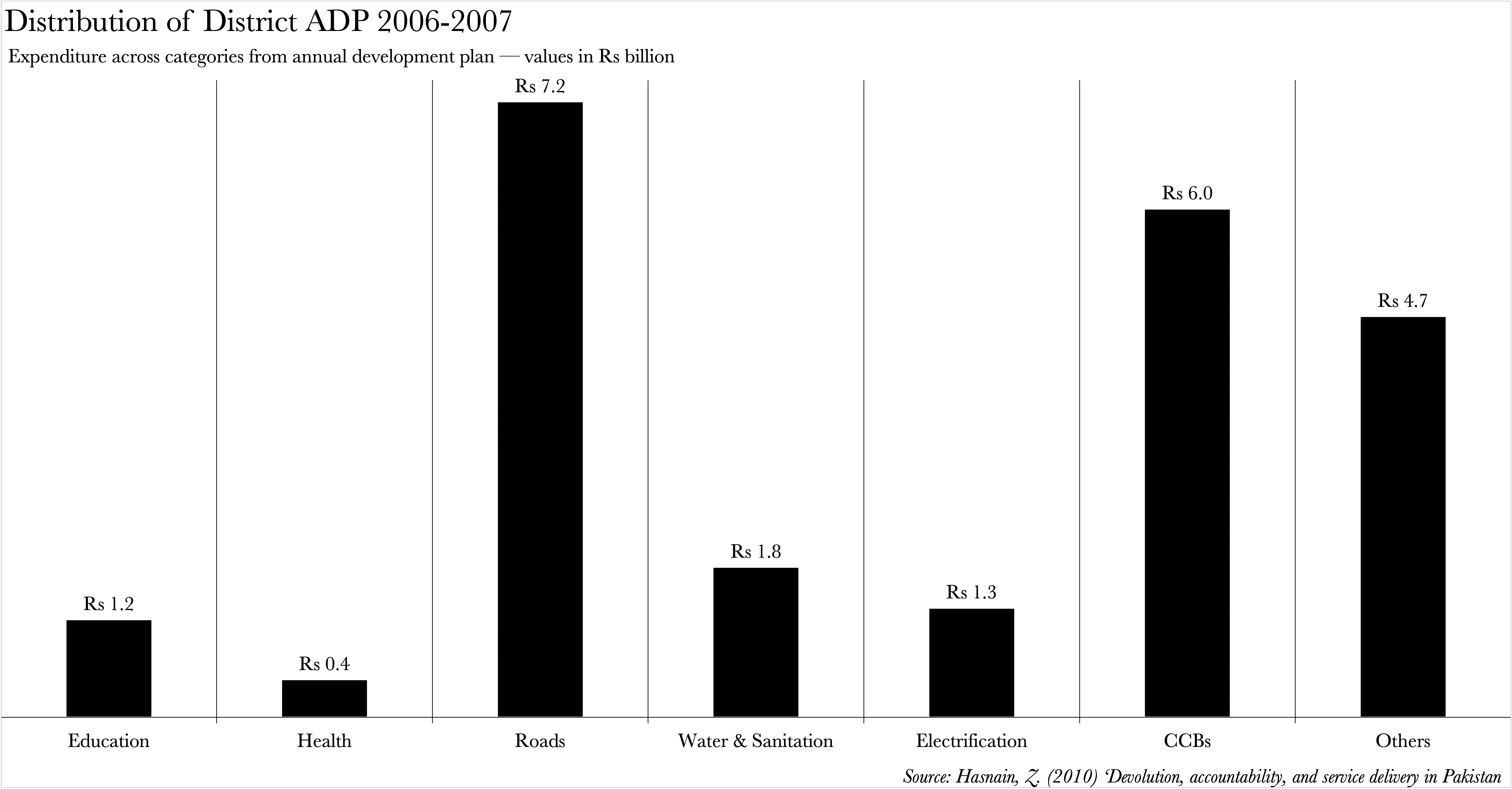

A cursory examination of the provincial and district development expenditures in Punjab from 2006 to 2007 reveals a striking emphasis on physical infrastructure. These projects, while small-scale, are tailored to meet the specific needs of individual neighbourhoods.

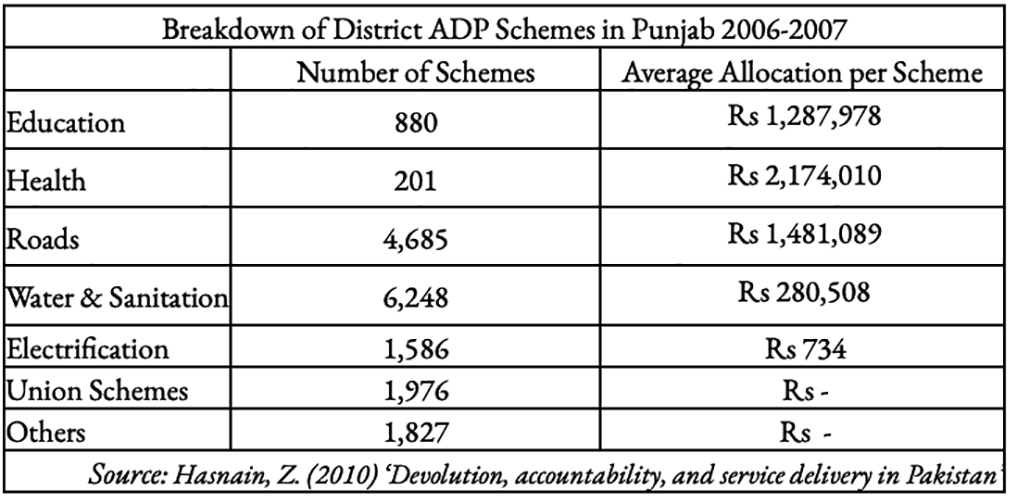

Of the Rs 23 billion collectively allocated in their annual development plans during the aforementioned period, a significant 46% was earmarked for roads, electrification, and water. If we discount the mandatory 25% that was allocated to citizen community boards, then a staggering 64% of the total discretionary funds of the local government were allocated to these categories. The localised nature of these projects is evident in the average outlay: Rs 1.5 million for a road and Rs 300,000 for a water and sanitation scheme. The expenditure itself ensured that these initiatives were designed for the immediate gratification of the local government’s constituency, rather than for broader, cross-provincial appeal.

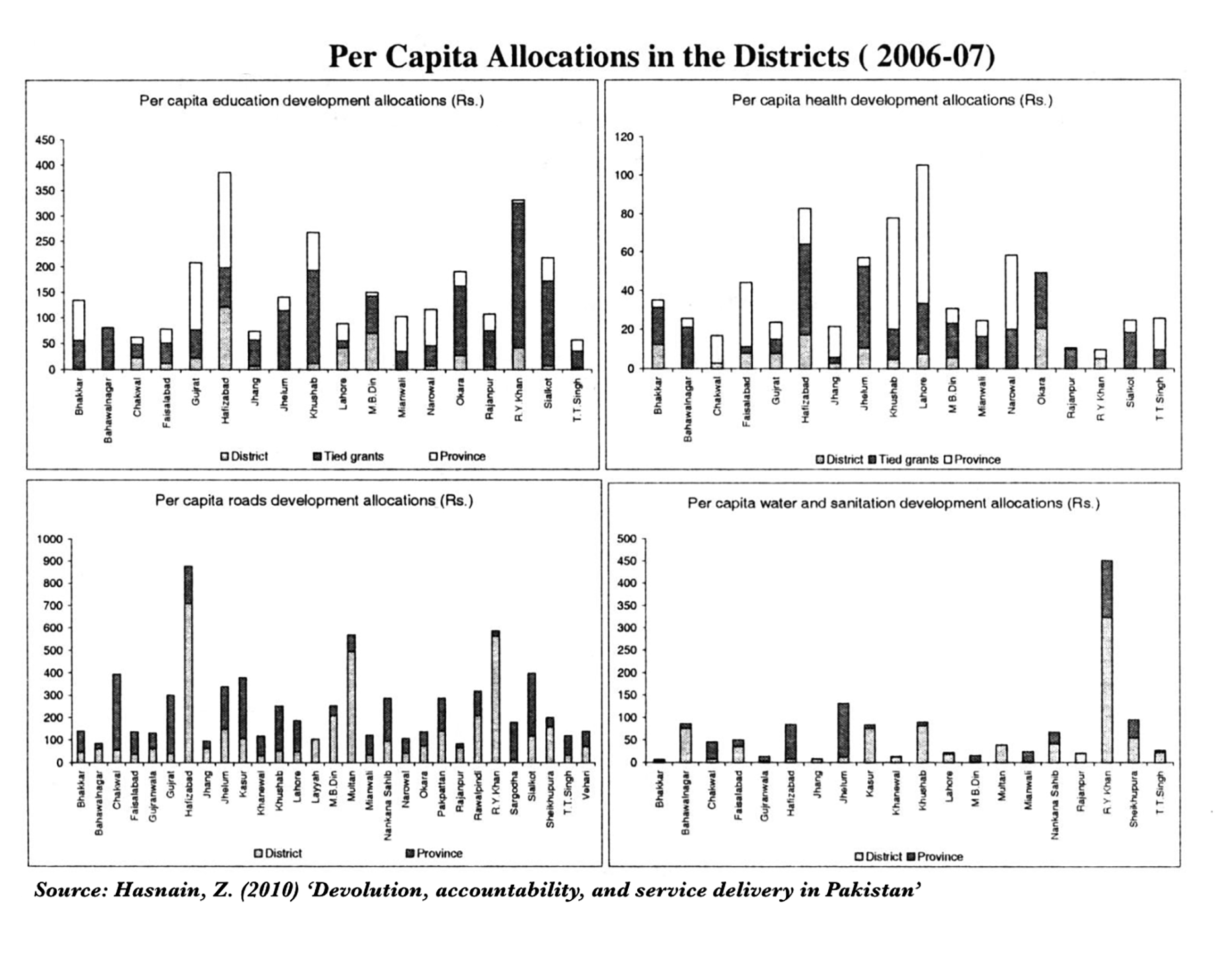

Furthermore, local governments also mitigate the bias that provincial governments have for dedicating expenditure to their own heartlands. Examining the data further reveals that in per capita terms, districts were out pacing the Punjab Government on various accounts for developmental projects. The logical consequence of this is more equitable distribution of development across the province.

Healthcare and education were the only notable gaps in local government spending. Could it be that these crucial sectors were met with indifference by local governments? We cannot say for sure. However, what we do know is that the Punjab Government launched the Punjab Education Sector Reform Programme during this period, and also invested heavily in basic health units.

It is reasonable to assume that these provincial initiatives influenced the choices of local policy-makers. The task of claiming credit for a service becomes a labyrinthine endeavour when multiple tiers of governance partake in its provision. Such a scenario can engender incentives for politicians to shift their focus towards targeted benefits or on more conspicuous interventions. Furthermore, there is no detriment in district governments ceding some areas to the province.

“Some responsibilities transcend the purview of local authorities. Highways, perhaps, are more fitting for the provincial government’s attention, while motorways may be more aptly handled by the federal government,” posits Mehboob.

It is not far-fetched to imagine that district administrations deferring to the province on these issues was not a grave mistake. Perhaps it was not an error in the slightest. One conceivable rationale for districts prioritising physical infrastructure is its inherent ‘diversity’ compared to social infrastructure. Roads and drains exhibit a variety in size and form, whereas primary schools and basic health units maintain a relative uniformity. This diversity paves the way for ‘specialisation’, empowering district policy-makers to focus on and claim credit for smaller, local schemes, and provincial policy-makers to claim credit for the larger ones.

A survey conducted by the Devolution Trust for Community unveiled that the majority of reasons for contacting union councillors, as reported by both male and female respondents, pertained to personal issues such as financial assistance, identity card issuance, police-related problems, or disputes. Those who reached out for service delivery reasons did so primarily concerning water, roads, and electricity. A mere 2% of respondents sought local officials for education and health matters. If these were the driving factors behind public interaction with their local government, then it is evident that the local government was indeed responsive to the people’s demands at the time.

Let us revisit the issue. In a developing country, service delivery implies basic infrastructure development. The local governments, when fully empowered, accomplish precisely that. Moreover, they launch projects at a scale that is tailored for their own district and, consequently, cater only to those people whom they represent.

This seems rather obvious. If the criterion of service delivery is to enhance physical infrastructure in your district, then local governments are superior. If anyone is casting their ballot for their prospective legislator, hoping they will resolve these local infrastructure problems, then they would have been better off with the local governments of two decades ago.

Nonetheless, constituents will still harbour expectations that this year’s elections will impel their legislators to emulate what their local governments accomplished years ago. This not only culminates in unfulfilled promises and resentment but may also result in subpar legislation. What if a significant number of these legislators harbour no authentic interest in being part of the legislature to begin with? What if their sole purpose is to serve their constituents in whatever capacity they can?

The better legislator question

A prevalent contention posits that legislators ought to concentrate on legislating, eschewing administrative duties. To put it differently, a legislator hailing from the provincial or national assembly should immerse themselves in their respective assembly’s debates, rather than diverting their focus to, for instance, the construction of a stadium. This, however, is a contentious issue. Let us examine both sides of the argument, and proceed from there.

“The constitutional mandate of local government, if properly implemented, would transform our lawmakers from contractor representatives to bona fide legislators, compelling them to extend their concerns beyond mere roadworks, local waterworks, and gas and electricity connections,” proclaims Abdul Moiz Jaferii, a Senior Partner at HWP LAW Waheed Masood Jaferii Kayani.

“Robust local governments would also amplify the incentive to become a lawmaker. It would revolutionise the political status quo, where the majority of individuals currently vying for provincial assemblies would then covet a mayoral ticket within their own constituencies,” Jaferii adds.

Now for the other perspective.

“Legislators at all tiers of government, be it the provincial assembly or the national assembly, juggle both legislative and executive functions. We elect a cohort of individuals tasked with overseeing the bureaucracy and the legislature,” posits Umar Ijaz Gilani, a Partner at Law and Policy Chambers.

“For instance, a member of the national assembly could potentially ascend to a ministerial role or find themselves in a position to hold a minister accountable. Similarly, those elected for the district assembly, the union council, wield the authority to enact certain rules for the governance of the union council,” Gilani expounds.

One potential reconciliation of these divergent opinions lies in the scarcity of options, or elected avenues in this context, for individuals to partake in. While it would be fallacious to assert that all legislators aspire to be administrators, it is not incorrect to suggest that a significant number might harbour no interest in the legislative assemblies to begin with and are only present due to a lack of alternatives.

PILDAT’s report on the performance of the 15th National Assembly (the outgoing one) revealed that the average attendance of members of the national assembly in their five-year tenure was recorded at 61%. It also discovered that out of the 218 members, 50 refrained from speaking for even a single minute. Clearly, a few would prefer to be elsewhere. Looking back at history, we see this to be indisputably the case.

The newly elected members of the provincial assemblies in 2002, many of whom had been seasoned politicians, discovered that this time around they had been stripped of their real power at the constituency, local, and grassroots level. Their authority and influence had been supplanted by a novel invention — that of district governments. With numerous provincial functions ostensibly devolved to the district level, the role of the provincial government and its representatives had been reconfigured in a way that did not favour them. District governments and their nazims, perhaps for the first time in history, were in a position to contest, at least theoretically, the provincial monopoly of power.

As a result, many provincial assembly heavyweights opted for the local government offices. Salim Jan Khan Mazari is a prominent example. A provincial assembly veteran, he secured a national assembly seat for Kashmore only to resign later and get elected in the local government. Other notable District Nazims (Mayors) include Shah Mahmood Qureshi, Faryal Talpur, and Nafisa Shah, among others.

It is noteworthy here to also emphasise that the 2001 and 2005 local government elections witnessed higher voter turnouts than the 1993, 1997, and 2002 national assembly elections. It is reasonable to infer here that if the local governments were empowered and esteemed as their counterparts, then not only would there be a better distribution of candidates across each tier of government, but also a better performance.

Beyond the aforementioned superior service delivery aspects, national and provincial legislators are not as potent as we perceive them in terms of implementing projects for their constituencies. The person orchestrating the affairs in the ultimately is the Chief Minister, through the bureaucracy. It is not the members of the provincial assembly. Legislators from the two assemblies can merely propose projects whilst sanctioning and executing them is contingent upon the Chief Ministers and the provincial secretaries.

It is a poor deal for any legislator who wants to make a difference in their district. It is also worse for anyone expecting their legislator to improve their constituency — obviously excluding a certain class of legislators.

So, to revisit the main point. Local governments would have facilitated better service delivery and legislation, however, they currently lack the capacity to do either.

If improvements on the past cannot sway one to revisit local governments, then what if we said that the current constitutional crises might have been mitigated at least if there had been an effective local government mechanism.

Could local governments have mitigated the current constitutional crisis?

The current constitutional crisis stems from the leader of the House in Parliament deciding that one day he could no longer tolerate sitting in the House to begin with. One perspective to consider is whether there existed a mechanism to deter a political party from deserting the national assembly, along with two provincial assemblies?

“Democracies can only thrive where there is political commitment to the institutions of democracy from rival political forces. It will be easier to foster that commitment if there are multiple tiers of government because every political actor will have the incentive to stay in the system so that he can continue to wield power at one tier or another,” asserts Gilani.

Then there are the caretaker government(s). This batch of caretaker governments is set to be the most famous that we have ever seen. While one can argue about what a caretaker government can and cannot do, it is likely that everyone can concur that having the roads of Mall Road scrubbed clean to combat smog is rather ludicrous.

“If we had efficient local governments who were in charge of policing and land revenue matters, then the need for a caretaker government at the provincial level would be diminished,” affirms Gilani.

The caretakers are perhaps the best note to end on. While many have scorned the caretaker governments for overstaying their welcome, their district counterparts — the district administrators — have been equally guilty of overstaying their welcome in local governments for decades. Similarly, while we chastise the caretaker governments for certain initiatives that might overstep their mandate, our provincial governments are equally culpable of violating the rights of local governments with impunity.

This is not to insinuate that one violation begets another, and that curbing one will necessarily curb the other. However, it is conceivable that if our legislators were not burdened with the task of resolving issues related to electricity transformers in their districts, they could have focused their energies on crafting superior laws that might have circumvented the current constitutional impasse.

Really its a fantastic and inspiring article.