By now, the rise of electronic payments in Pakistan is quite clear and has been covered extensively by many publications, including this magazine. What is less clear is that what should be the implication of the rise of digital payments – that the proportion of payments in Pakistan made in physical cash is going down – has not happened yet, or at least not nearly as much as the rise in digital payments might imply.

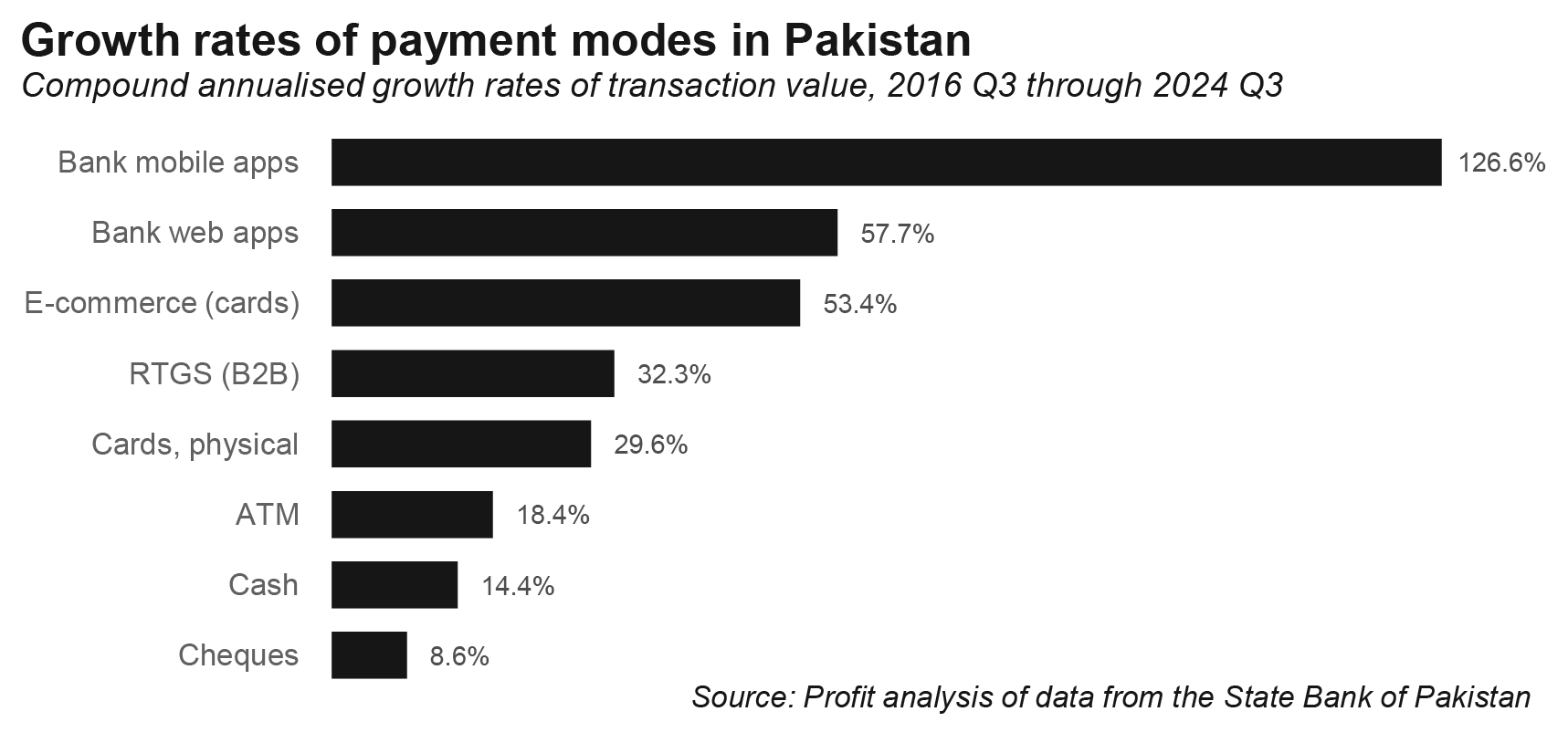

During the third quarter of 2024, digital payments – bank apps, websites, and card-based e-commerce payments – have increased to approximately 9.3% of the value of all transactions that take place in Pakistan, up from just 0.3% in the same quarter in 2016, which is a nearly 31x increase in market share for digital payments, according to data from the State Bank of Pakistan.

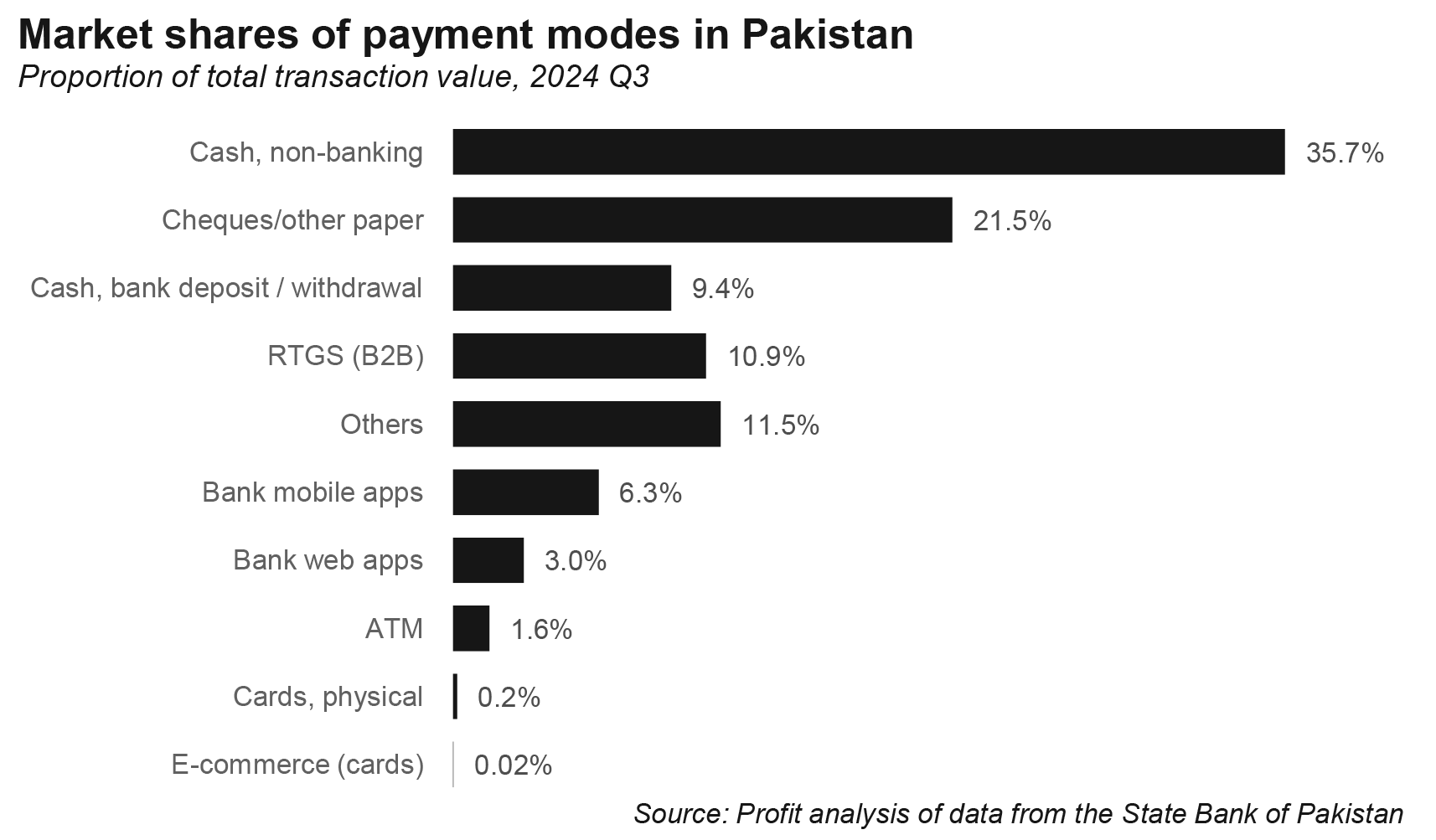

You would think that cash would have fallen by a corresponding percentage, but you would be wrong. According to Profit’s estimates based on data from the State Bank, the proportion of transactions in Pakistan that took place purely in physical cash (which means excluding cash deposits and withdrawals from bank branches and ATMs), were approximately 35.7% of the value of all transactions that took place during the third quarter of 2024. Eight years ago, in 2016, that number was 38.4%, so cash is down slightly from where it was almost a decade ago.

But not by nearly as much as that rise in digital payments number might have led you to think. The content in this publication is expensive to produce. But unlike other journalistic outfits, business publications have to cover the very organizations that directly give them advertisements. Hence, this large source of revenue, which is the lifeblood of other media houses, is severely compromised on account of Profit’s no-compromise policy when it comes to our reporting. No wonder, Profit has lost multiple ad deals, worth tens of millions of rupees, due to stories that held big businesses to account. Hence, for our work to continue unfettered, it must be supported by discerning readers who know the value of quality business journalism, not just for the economy but for the society as a whole.To read the full article, subscribe and support independent business journalism in Pakistan