Nothing can prepare you for the inevitable.

For most of the past six decades, banking in Pakistan has been dominated by the same five banks: Habib Bank, National Bank, United Bank, MCB Bank, and Allied Bank. There has been some movement in the order of the banks between them – in terms of deposits, National Bank was larger than Habib Bank from 1974 through 2012 – but that list has stayed the same. Yes, Bank Alfalah briefly cracked their ranks between 2005 and 2009, but it soon slipped in terms of market share once again.

The industry refers to them as the Big Five Banks. They think of themselves as the Big Five Banks. Because they are the Big Five Banks, and their dominance has not seriously been questioned.

Until now.

Nothing can last forever, and there is absolutely nothing ordained that these five must remain the biggest banks in the country, and their middle market competitors certainly do not view the structure of the market that way either. But there are two banks in particular – Meezan Bank and Bank AL Habib – that are looking to seriously upend the established order at the top of Pakistan’s banking system.

Both banks have very different histories, and have very different strategies for growth. Meezan Bank is a pure-play Islamic bank and while Bank AL Habib does have an Islamic banking division, it accounts for a relatively small percentage of its business, with the bulk of Bank AL Habib’s growth coming from conventional banking.

In other words, both banks have risen to the threshold of Pakistani banking’s most exclusive club by taking different paths towards answering a question that has been on the mind of every Pakistani bank CEO over the past decade: just how important is Islamic banking to the sector’s future? A look at the growth trajectories of these two banks might provide some clues, and which bank has the better prospects might help determine the answer to that question.

To help answer that question, Profit dove deep into the respective histories of these two banks – and their financial statements. We sought comment from their management teams, but were not able to get a response in time for publication. Should we receive a response after publication, we will update the web version of this story accordingly.

But this much is certain: by mid-2021, the list of the largest banks in Pakistan will be very different than it has been for the past six decades. And with that will change both the nature and variety of financial services available to Pakistani individuals and businesses.

Two banks, two histories

Of the two banks, Bank AL Habib has the longer history, and not just of the legal entity. The Habib family are possibly the oldest Muslim business family in South Asia that are still in business. Indeed, they started business in 1841, a full 27 years before Jamsetji Tata started the Empress Mill in Nagpur that became the foundation of the Tata Group.

The group is named after Habib Esmail, the most prominent patriarch of the family, who joined his relatives’ business in 1891. Habib’s two sons – Mahomedali Habib and Dawood Habib – created Habib Bank in Bombay in 1941, starting the family’s foray into banking, the industry that has now become the core of the family’s holdings and wealth, and the institutions they have set up have become a bedrock of the Pakistani financial system.

In 1947, the Habibs showed the value of having a financial empire to the government of Pakistan. At Partition, when a dispute arose over how much of the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) assets would stay with the RBI and how much would go to the newly created State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), Mahomedali Habib wrote a blank cheque and handed it to Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the country’s founder and incoming Governor-General. Jinnah wrote in Rs80 million.

Yet despite that contribution to Pakistan’s early financial stabilisation, the Habib family found themselves subject to Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s nationalisation drive. On December 31, 1973, members of the Habib family were forced to walk out of the offices of Habib Bank Plaza in Karachi – then the country’s tallest building – and to forcibly hand over control over the bank their family created to the government of Pakistan. The very government of Pakistan they had bailed out when it needed them the most.

It would be the last time the family would ever run that bank.

But when the government of Pakistan – under then-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif – announced in 1991 that it would permit private sector entities to once again apply for banking licenses, among the first in line were not one but two branches of the Habib family. Bank AL Habib was created that same year (the other branch of the family created Metropolitan Bank in 1992, which later became Habib Metropolitan Bank.)

Given the family’s origins in trading, Bank AL Habib has a strong foothold in financing trade, but they have since expanded their footprint towards working capital financing and even longer-term financing for manufacturing businesses. The bank now has one of the most diversified sets of clients in the banking industry. More interestingly, the bank has remained largely committed to conventional banking at a time when other banks have sought to jump headlong into Islamic banking. Bank AL Habib does have a large and rapidly growing Islamic banking division, but the bulk of its growth has come from its conventional business.

Meezan Bank’s history is a lot newer. It originally started off in 1997 as Al-Meezan Investment Bank, an Islamic investment bank, since the State Bank of Pakistan used to have the same policies as the RBI, which had initially made it difficult for Islamic banks to exist as deposit-taking institutions from retail customers. The bank was created by Irfan Siddiqui, its first CEO, who raised the financing for the creation of the bank from investors in the Gulf Arab states. Siddiqui was then the general manager of Pak-Kuwait Investment Company.

In 2001, Siddiqui turned his attention full time towards managing Meezan Bank and seeking to convert it into a full-fledged, retail deposit-taking, Islamic bank after the State Bank changed the rules to allow the creation of such entities. And in true Pakistani banking form, they sought to bolster the new entity’s credibility by buying out the operations of a foreign bank looking to exit the market, in this case, the Pakistani branches of the Paris-based Societe-Generale.

During the first few years of operation (the bank’s first full year was 2002), Meezan Bank had a hard time getting Pakistan’s major corporations to take it seriously as a competitor. All of them had relationships either with existing local banks or with some of the multinational banks. An Islamic bank was not something they readily understood, particularly when Meezan Bank told them that their loans would have a greater level of scrutiny than its conventional peers.

So Meezan Bank – which had no trouble attracting deposits from Pakistan’s religiously-minded Muslim population – began lending to small and medium-sized businesses, some of whom may have previously avoided banks entirely because they were owned by religious people who did not want to partake in the conventional banking system.

Note the difference in clientele that Meezan and Bank AL Habib had: Meezan relied on smaller businesses that may have previously avoided borrowing altogether. Bank AL Habib was able to rely on the Habib brand name which would have made it easier to attract business from some companies that may have previously been clients of Habib Bank. Meezan Bank had to grow its client base from the ground up, whereas Bank AL Habib had somewhat of a head start.

Both companies – however – had significantly smaller balance sheets than the Big Five banks and hence had to rely on lending relationships with mid-sized companies rather than the major multinational corporations or the larger local companies, at least initially.

Islamic vs Conventional: a difference in options

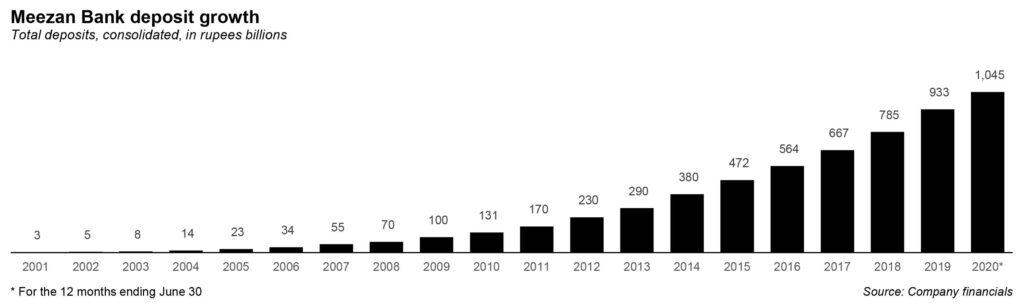

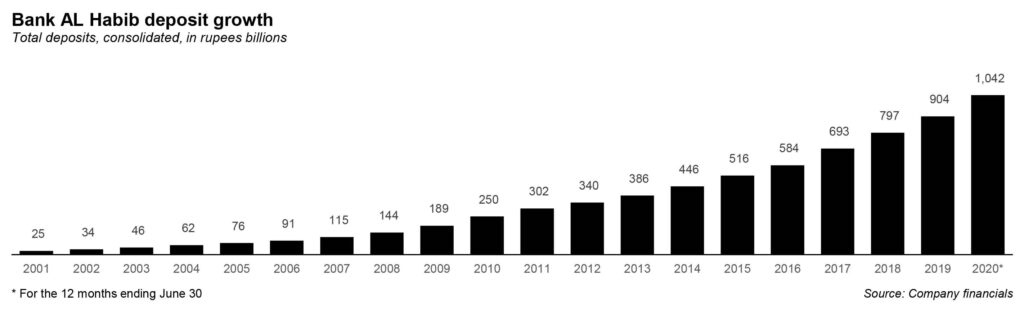

So, what are the results of that strategy. In terms of deposit growth, there is almost no contest: Meezan Bank has been growing a lot faster than Bank AL Habib for almost every single period we examined since 2001, when the bank first got its license and came into existence. Indeed, over that 19-year period, Meezan Bank has grown its deposits faster than Bank AL Habib for 17 of those years, with Bank AL Habib outpacing its Islamic rivals in just two years over two decades.

The numbers speak for themselves: since 2001, Meezan Bank’s deposit base has grown at an average rate of 37.7% per year, while Bank AL Habib’s deposits have grown at 22.1% during that same period. The industry as a whole grew by an average of 14.8% per year during that time.

Now, one might argue: well, of course Meezan Bank’s growth numbers look good: they were starting from a lower base. So is this not just a low base effect showing up in the growth numbers? Yes, but also no.

It is true that Meezan Bank had deposits of just Rs3 billion on December 31, 2001 while Bank AL Habib had nearly Rs25 billion. Meezan Bank, however, not only grew faster than Bank AL Habib, but is now larger even in absolute terms. As of June 30, 2020, the latest period for which both banks’ financial statements are available, Meezan Bank had deposits of Rs1,045 billion to Bank AL Habib’s Rs1,042 billion. Meezan overtook Bank AL Habib as the sixth largest bank in Pakistan by deposits in 2019.

And those higher growth rates are reflected even for more recent time periods, when both banks had massive balance sheets. Over the past five years, for instance, Meezan’s deposits grew by an average of 19.6% per year compared to 15.1% per year for Bank AL Habib and 12% per year for the industry as a whole.

Indeed, in previous interviews with this scribe, Meezan Bank’s management are quite possibly the only ones who have never once expressed any concerns about how to grow their deposits. Being the oldest pure-play Islamic bank in a country filled with religious Muslims has its advantages: Meezan can simply set up a branch just about anywhere and watch the deposits just flow in almost automatically.

By comparison, Bank AL Habib has had to work a lot harder to raise its deposit base, especially since it is competing against all of the other conventional banks in the country. While the bank has a large market share in Karachi, the country’s financial capital, it has faced a more competitive environment when expanding its business footprint in the rest of the country (though it has been considerably more successful at this than the bank named Habib: Habib Metropolitan Bank).

For Meezan, the core challenge has been deploying the deposits it is so easily able to raise into profitable lending opportunities, a task made considerably more difficult by the fact that the government of Pakistan issues very few Islamic bonds. Most other banks are able to raise deposits and plow that money lazily into government bonds. While Meezan can do that to some extent, the dearth of Islamic government bond options means it has to get more creative with respect to its lending practices.

Hence, Meezan innovated with respect to consumer lending in a way that most other banks avoid. Islamic borrowing options are something that many religiously minded consumers value, and Meezan has been able to create several options for those customers. Meezan’s bankers do the usual consumer lending products common in developed markets but far less common in Pakistan: mortgages, auto lending, and even Islamic credit cards.

But Meezan also took their consumer lending division one step further, introducing direct appliance purchase lending as well. The bank was the first in Pakistan to start offering loans to purchase laptops, for instance, and its consumer finance division remains among the largest in the country.

Meanwhile, Bank AL Habib is able to invest a considerable portion of its deposits into government bonds, and hence does not face a particularly acute need for innovating on its lending side. Indeed, Bank AL Habib is proudly old-fashioned about its lending practices. It does not like advertising its credit card, for instance, and only introduced the product very reluctantly, initially offering it ‘by invitation’ to its oldest clients.

Bank AL Habib likes offering the kind of loans that have existed for centuries: lending for working capital needs, or trade financing, often collateralised, and usually very low risk. And, of course, they – like every other conventional bank in Pakistan – love lending to the government in the form of investments into government bonds.

That difference in options is visible in their lending books. Meezan Bank is only able to deploy about 30% of its total lending book into Islamic government bonds, whereas Bank AL Habib puts about 53% of its lending into government bonds. Meanwhile, about 7% of Meezan’s total lending is in consumer financing, whereas Bank AL Habib’s consumer financing is just 2% of its total lending.

Which one will win out?

So let us now return to the question we asked at the beginning of this story: which bank has the better growth prospects, and what implications does that have for the relative importance of Islamic banking to Pakistan’s financial services sector?

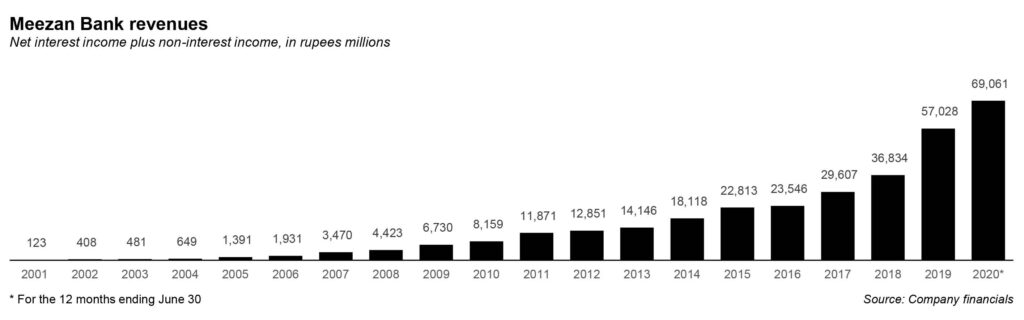

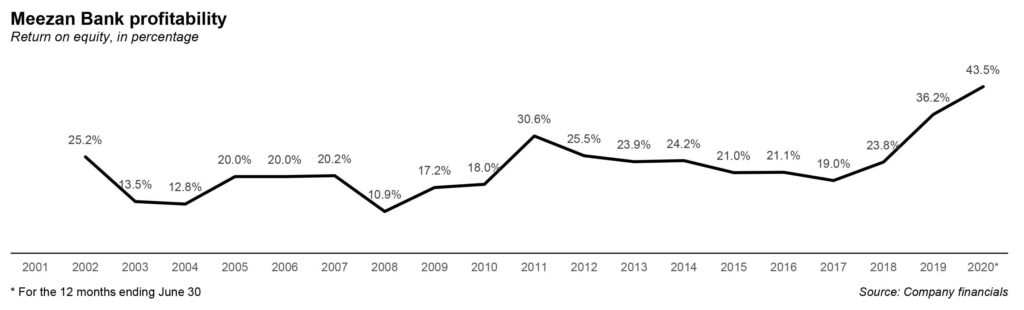

On the surface, the answer is obvious: Meezan has been growing faster – and is far more profitable – than Bank AL Habib. But digging a little deeper, and one finds that the answer may be somewhat more complex, and that Bank AL Habib cannot be ruled out as a competitor for a place in Pakistan’s Big Five banks.

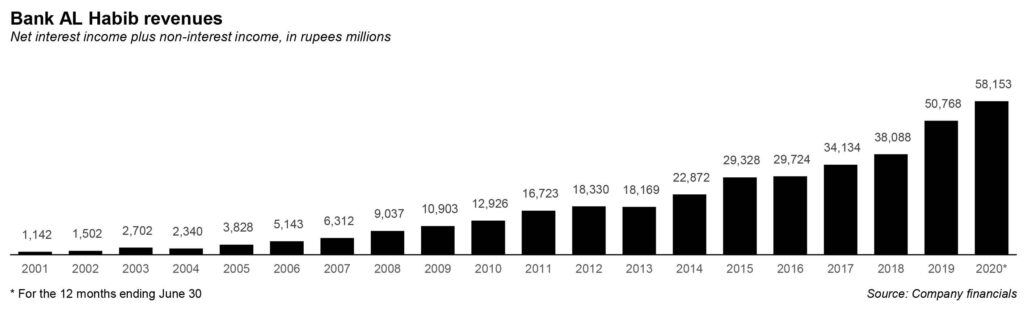

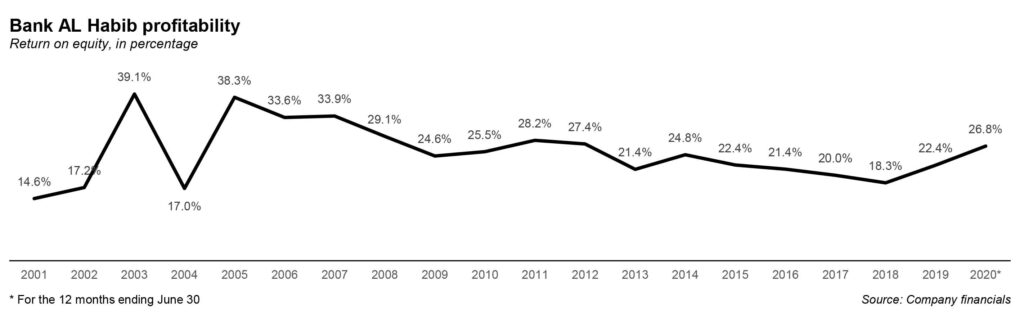

In terms of profitability, Meezan Bank is easily the single most profitable bank in the country: its return on equity – the single most important measure of a bank’s profitability – is the highest in Pakistan, bar none. During 2019, Meezan Bank’s return on equity hit 36.2%, several percentage points higher than the next highest bank: Standard Chartered Bank Pakistan, which had a return on equity of 23.8% during that year. Bank AL Habib was the third highest at 22.4% during a year when the industry as a whole averaged a 12.8% return on equity.

In other words, Meezan is not just making the most of a bad situation by lending to the private sector – and to consumers – just because it cannot buy conventional government bonds. It is lending more profitably than any other bank in Pakistan, meaning it is not just lending to bad credit risks. It is actually good at finding good credit risks and then lending to them.

But both return on equity and deposit growth are backward looking indicators. They tell us that Meezan has been the better bank to bet on over the past two decades. It is not necessarily a good predictor of what happens over the next two decades.

To examine that, we will need to dig deeper into trends to examine not just the rate of change, but the rate of the rate of change. In calculus, this concept is called the second differential [d2y/dx2, for those of you who learnt calculus via the shortcuts], and it can be a useful tool in understanding future trends.

The key to Meezan’s success has been its dominance of the Islamic banking industry, which is the fastest growing segment of the broader banking sector. Since 2002, conventional deposits have grown at an average of just 12.9% per year, while Islamic banking deposits have grown at an average of 38.5% per year during that same period.

Over the past decade, despite the entry of virtually every single conventional bank into the Islamic banking industry, Meezan Bank’s market share of the Islamic banking industry has remained between 33% and 36% in any given year. So in order to understand Meezan’s growth prospects, one needs to understand just how big the Islamic banking industry can grow.

On that front, the second differential becomes important: how much of the new growth in deposits is being captured by Islamic banks? What percentage of the net new deposits that enter the Pakistani banking system every year are Islamic? That should give us some idea of just how big this industry can grow.

While Islamic banking currently accounts for 18% of total deposits as of the end of 2019, according to data from the State Bank of Pakistan and Profit’s analysis of the financial statements of every single bank in the country, it accounts for about 20% of net new deposits between 2002 and 2019. Crucially for the industry, net new Islamic banking deposits hit approximately 30-35% of total industry net new deposits, and have failed to go higher since then.

That seems to suggest that Islamic banking likely has a limit on its growth: approximately one-third of all deposits at some point in the future will be Islamic banking deposits, if current trends do not materially shift. And given Meezan’s steady market share within that market, that implies Meezan’s market share has a ceiling of somewhere between 10% and 12% of the total banking market.

Meezan Bank currently accounts for 6.1% of total banking industry deposits, which means it can continue growing significantly over the next few years. But if a 10-12% market share is its ceiling, that would place it at roughly the same market share as United Bank Ltd is today. In other words, the best case scenario for Meezan Bank is to become the third largest bank in the country.

By contrast, because Bank AL Habib offers both conventional and Islamic products – and has still managed to grow significantly faster than the Big Five – that implies that there is not necessarily a ceiling on its market share. It has a slightly longer climb than Meezan, but it is unlikely to hit a wall later on down the road.

Ultimately, it seems that not limiting itself to one set of customers is likely to be the winning strategy in the race to become one of the largest banks in Pakistan.

Meezan bank doesn’t have Islamic credit cards, or any credit cards for that matter.

Islamic banks do banking which is asset based. Without asset at back no Islamic banking. With the passage time Islamic market will get developed further strengthening IB.

Article covers what all these two banks have done and where their success lies. However I’m still not sure how they will enter the ranks of the so called “Big 5”. Analysis in the article does not match with what the title states…

This article could have used deposit figures of different banks which are easily available.

Impressive read! Conventional banks with Islamic windows are lagging behind due to a primary reason that Meezan is solely a Islamic Bank. To speak the truth, whenever a lay person is told to open an account and he is looking for Islamic product, Meezan Bank is the word of mouth. A small correction though, Meezan Bank is againt cash lending, so does not offer credit cards.

Since this article has not provided data on big 5 banks, growth prospects of those banks will change with the range of newer services and customer focus actions.

Thank you

Shafique

Well that brings a new era of competition in the market.

Meezan and Bank Al Habib performance very well in term of deposit procurement, easy financing, and most importantly trade business, they already cracked their way to enter in big 5 club in terms of profit and financing, and it seems very deposit base ll also be crossed in near future,

Moreover NA senate has already backed the resolution of allocating reasonable share of Govt business to islamic banks, this will pave the way to enter in this prestigious club of big 5,

Proud to be a share holder of meezan bank Ltd since its ipo. In next 5 years Meezan bank in big 5.mebl share profits with its share holder that is why mebl growing bank. Mebl ipo rs 12.25 was under subscribed. I have No plan to sale mebl shsres. Best bank. Best management. Masha Allah.