When Ali Noor’s bank came to his mid-sized mart called KNM Mart and put up a QR code at the mart for free, Ali was intrigued and a little excited. The bank explained to him how it would all work, and if people ended up using the QR code to make payments, it would be efficient both for the mart and for its customers. However, as Ali soon discovered, the QR code went pretty much ignored with very few people actually trying to use it to make transactions.

When it became clear that the QR code would be used once or twice in a week on a good week, a representative from the bank visited again. Except this time, they weren’t here to try and find out why this was happening or to do something about it. “They came and removed the QR from our mart, saying that there were not enough transactions coming through,” the mart owner said.

And in this little anecdote, ladies and gentlemen, lies the tragedy of digital payments in Pakistan. For starters, not all mart owners or shopkeepers are like Ali, and are in fact distrustful of QR codes. When the banks come to take them away, they breathe a sigh of relief at this strange new method finally not being around. Customers as well, clearly, are in no mood to try this new method of payments. This much is obvious, especially considering how most Pakistanis do not use the POS method to pay for things, QR codes were a far cry. The complexity of the question is why people are hesitant to make transactions on QR codes?

The permeability of smartphones and cheap internet data has only increased over the years in Pakistan and is only expected to increase even more. As the government tries to bring more of the population into the banked fold, QR payments make sense. QR codes are easy to place, are less costly, and have more benefits for merchants as compared to payments in cash or through debit or credit cards.

They take no time, there is no worry of handling or taking care of a card, and you can see in real time money coming in and out of your bank account.Yet, QR codes have failed to gain traction in Pakistan. The payment journey, discount fueled growth, strategic errors in business decisions, lack of interoperability, lack of users with mobile banking applications, lobbying by competitors and a deeply entrenched status-quo that has eventually led to lack of competence in digital banking might be the reasons that QR codes for payments have not been able to gain serious momentum.

If harnessed, this momentum could culminate in a revolution in the payments space in Pakistan. It is an alternative to POS machines that have higher MDRs that make it unattractive for small merchants to enable POS transactions via payment cards at their location. Since the majority of the merchants in Pakistan operate at a small scale, enabling them for QR transactions holds the potential to transform the payments ecosystem in Pakistan and make it wholly digital.

Payment schemes, banks and fintech companies have all had their days of experimenting with QR codes for digital payments in Pakistan. UBL was the first one to launch QR codes in Pakistan with the collaboration of Mastercard in 2015. It was followed by Finja and FonePay, EasyPaisa, JazzCash and HBL, all of whom tried cracking the QR payments space. Some fizzled out in the process completely like FonePay, some limited their operations to a small scale, while others are still trying to make it through the thorny QR payments journey in Pakistan.

The QR payments journey

You have, of course, seen them (even if you did not realise it or pay attention at the time). The average reader of Profit goes to restaurants, and must have at some time or the other seen a small card that you scan with your phone and it shows you a menu. That is essentially what a QR code is, and they are everywhere. The Lahore Museum has them up on certain displays so you can scan the code and the information about the exhibit pulls up on your screen. Anyone can easily and conveniently create a QR code and anyone can scan it hassle free.

That is all it is. It is a barcode that is machine readable and can store data that can be retrieved when the QR code is scanned. Similarly, it can also be used to make payments. So you can walk into a mart, purchase groceries and instead of making payment via cash or debit card, you can simply scan the QR code placed by a bank at a merchant and make payments swiftly and safely.

This means you now have three options to make payments. Say you go to a restaurant. You can either pay in cash, or make payment via debit card or credit where the restaurant will simply take your card, swipe it on a POS machine. The transaction is carried out electronically with no cash exchange involved. All the monetary exchange takes place electronically between your bank and restaurateur’s bank electronically. Then we have the QR codes. The QR code payments journey for a customer looks something like this.

The restaurant will put up a QR code just like he has a POS machine. You would have to open your mobile application and scan the QR code. The mobile application will then ask you to enter the amount. Once you enter the amount and pay from your end, the transaction completion notification will go to the merchant who then confirms that the payment was successful. Somewhere between the transaction, you would have to put a one-time password for your application that you will receive on SMS or email. This is how all the QR code payments in Pakistan are currently made. And between cash, POS transactions and QR payments, QR payments seem to be ones that require a little more effort and maybe patience, given that cash and POS transactions are almost instantaneous.

“The QR payments journey is currently very manual and there is considerable room for improvement,” says Omar Moeen Malik, head of digital wallets and payment products at EasyPaisa. “Presently, it is the customer that is bearing the friction while making a payment via QR codes. He has to manually login to the application that requires internet connectivity. If he does not have internet connectivity on his phone, he can not make the payment. Then he has to enter the amount. If the amount entered is wrong, reversals can become a frustrating, painful process,” Omar adds. “And finally, the merchant has to wait for a confirmation SMS message to check the amount entered before the payment is considered complete”

Now this is a big problem. QR codes are supposed to make life easier but end up doing the opposite. To begin with, the number of mobile banking application users is small. According to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) Annual Performance Review 2020, the total number of mobile phone banking users in the country is less than 9 million. This means that less than 5% of the total population is currently enabled to use mobile banking applications and the number of users that can make QR transactions on these transactions are even smaller because not all banks that are issuers of these mobile applications have enabled QR payments on their respective applications.

An innovation in the payments space are NFC enabled cards for contactless payments. That is debit or credit cards on your phone that can be scanned on a machine to make payments. Though the speed of payment is quicker, the merchant needs equipment that is NFC enabled and the device at the merchant that initiates the payment costs somewhere around Rs25,000. Whereas a QR code can be made available for as low as $1 only.

“Some friction will always be there but we have to adopt the payment journey that has the least friction,” says Nadeem Haroon, country manager for UnionPay International in Pakistan. UnionPay International, also known as China UnionPay, is an international payment scheme that is headquartered in China that provides card services to banks. “What we follow here is the merchant presented QR code that is full of friction. In China, the most successful QR payment is the consumer presented QR code. The consumer generates the QR code and the merchant scans it. It is relatively closer to what a card payment looks like. Just like a customer giving a card to a merchant to make a payment, the customer would instead give QR code to the merchant to scan and complete the payment.”

Similarly, Omar says that instead of deploying static QR codes, we currently use in Pakistan, we can have dynamic QR codes in which the merchant generates a receipt with a QR code that has the payment amount prefilled. The customer only has to scan the QR code on that receipt and the payment is completed. This way, no amounts are being added by the customer. And the notifications can also go directly to the merchant’s computer system instead of his mobile phone. But dynamic QR codes require quite a bit of integration with the merchant systems. “In other markets, QR codes have evolved quite a bit. We are at an infancy stage and have a long way to go in terms of technology and product.”

The strategic errors

Up until now, the only reason people have bothered to use QRs for payments is to avail discounts.Though that might have led to an increase in transactions, it has kept people from using it on a daily basis, especially since enticing users with discounts is a horrible idea over the long term. This is connected with what we discussed above. Since QR code payments are full of friction, users won’t bear that friction unless there are discounts on it. But discounts mean that people will make transactions as long as there are discounts. It will drive transactions but not consistent usage.

Ammar Naveed Ikhlas, head of digital ecosystems and channels at Faysal Bank, explains to Profit that the market for QR payments is going to be developed on the basis of incentives and the schemes, so Visa, Mastercard and UnionPay, are giving these incentives to change customer behaviour, “Incentives can be in different forms. These can be discounts. These can also be rewards offered by banks and banks continue to offer these rewards,” he adds.

An example of such rewards are the Alfalah Orbits. On each purchase, Bank Alfalah adds Alfalah Orbits to customers’ accounts, which, when accumulated enough, can be used to make purchases by customers against which they would not have to make any payments. They can simply redeem those Orbits they accumulated as incentives against earlier purchases. “Over a period of time, it becomes a second nature and then you say you don’t want to carry cash. The fundamental is that you have to eliminate cash, and to do that you have to incentivise leaving cash,” Ammar says, explaining why incentives are necessary.

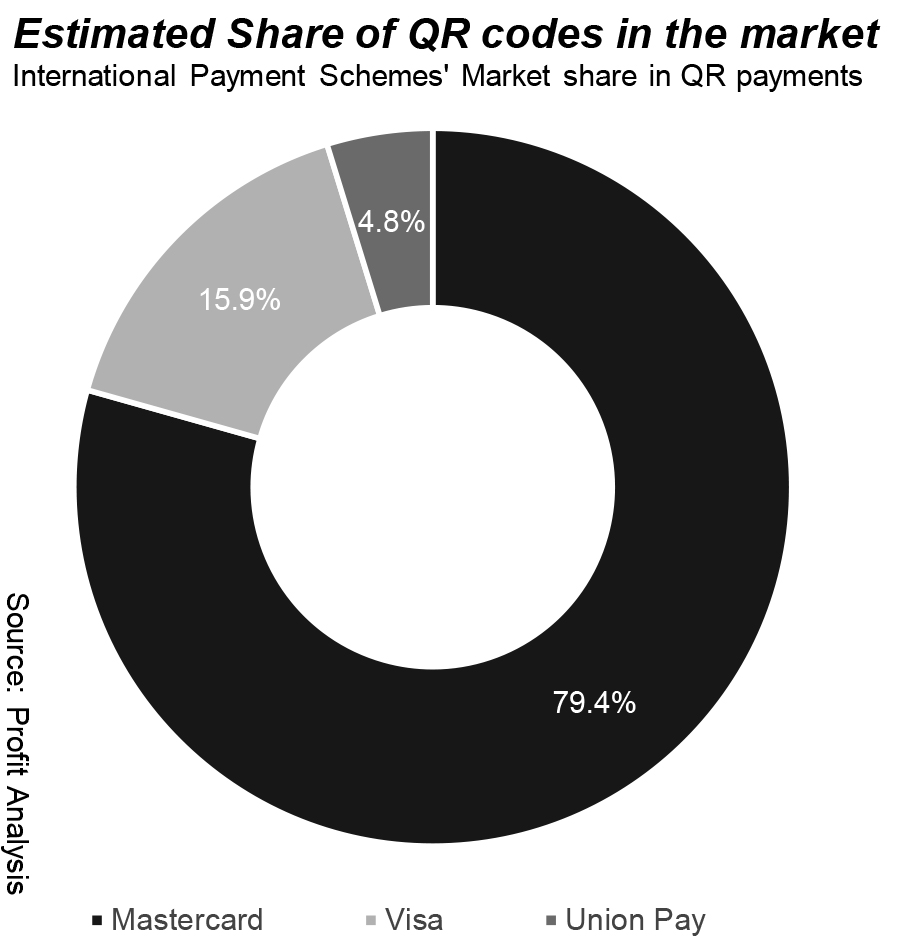

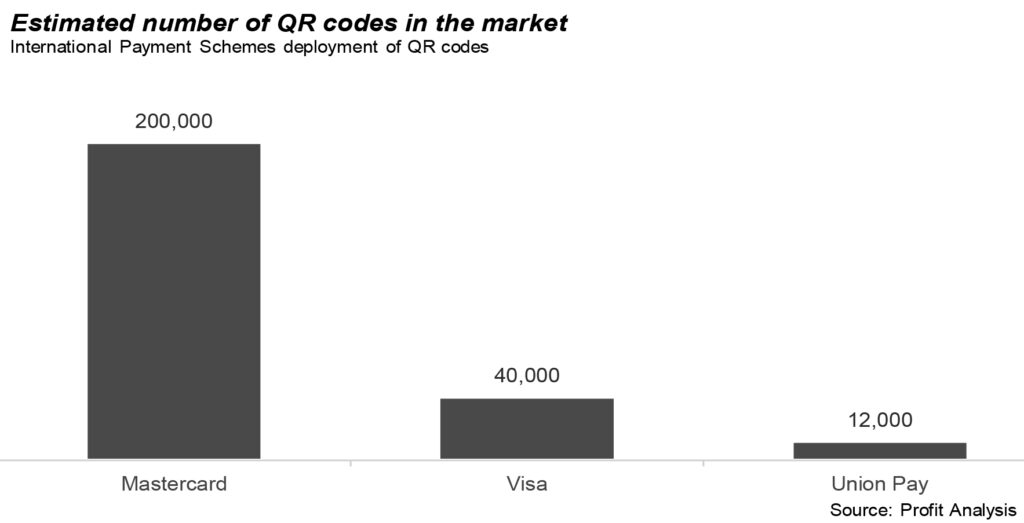

“People are using QR payments today to get redemptions,” says Atyab Tahir, country manager for Mastercard Pakistan. “International Payment Scheme-backed QR codes are being used because there is a redemption associated with it. QR transactions have usually been for a Rs100 burger or Rs100 pizza on discount and if the discounts are removed, transactions stop.”

What does this do? Discounts mean that transactions could be there and it might actually be a healthy number. But usage on a daily basis would be very limited. “This essentially means that payments via QR codes have been kept as a redemption tool and not as a transaction tool in the country,” Atyab explains.

International payment schemes have put in marketing money behind QR payments to get some traction, but that marketing money went to the wrong use case. For instance, the majority of people in Pakistan are not fast food eaters that would go to McDonalds or PizzaHut or KFC to eat. This strategy was driven by Mastercard which is the dominant player in QR space. When the majority of the QR codes were deployed at quick service restaurants (QSR), the usage was limited to what in this market is considered the affluent space. “If the use cases had been built in school fees or utility bill payments or grocery or kiryana stores or pharmacies, it would make more sense,” Atyab says.

When UBL partnered with Mastercard in 2015 to deploy QR codes, these were the times when mobile applications, through which users can scan the QR codes, were very limited in number and were new for banks as well as customers. “From the early days, all the players in digital payments have driven a wrong strategy when it comes to QR codes,” an industry expert who chose to remain anonymous told Profit. “When QR codes were initially launched, the practice was to deploy QR codes at locations where user concentration was measured according to the number of debit cards in that particular location rather than application users of a bank,” they explain.

For instance, UBL launched its pilot with Mastercard in 2015 in Karachi. QR deployments were based on cards but the functionality was of applications. This meant that the bank would deploy QR codes at places where card transactions were higher, whereas QR transactions were going to be done via applications. To be more specific, if Gulshan-e-Jauhar had more application users, QR codes would be more concentrated in Clifton where debit cards were high in number. It was the time when applications were newer for banks and customers. So you firstly have a limited number of application users and then you are deploying QR codes where there are little application users. Consequently, in a double whammy, QR transactions remained low.

“This was our first learning. That mobile applications rather than card usage should have been the basis of deploying QR codes,” he adds.

In another strategic error, QR codes were deployed at locations where there were POS machines already. “Now there is potential for QR transactions in high-cash markets like utility bills and school fees but we haven’t deployed that there,” says Atyab.

The banks themselves have shown a tendency to mistrust the possible success of the QR codes. For example, if someone is inclined to pay electronically, they are more likely to pay using POS than through a QR code. In the aforementioned scenario of the mart as well, the acquiring bank that put up the QR code at the mart, which in this case was HBL, also had a POS machine deployed at the same mart. The mart owner said that the transactions on the POS were visibly higher than QR payments.

The banks themselves have shown a tendency to mistrust the possible success of the QR codes. For example, if someone is inclined to pay electronically, they are more likely to pay using POS than through a QR code. In the aforementioned scenario of the mart as well, the acquiring bank that put up the QR code at the mart, which in this case was HBL, also had a POS machine deployed at the same mart. The mart owner said that the transactions on the POS were visibly higher than QR payments.

“Now, if you instead find a merchant that is using purely cash transaction, you can educate them about how they are losing 1-2% of value, spending effort in reconciling cash and spending effort in delineating how much money they took out from their cash box for domestic use etc, they will be inclined to change their ways. And once you offer them QR codes, you will get automatic reconciliation and no hassle of dealing with cash. So the cost of dealing with cash is high enough for people dealing with cash to incentivise people to shift to QR at kiryana stores,” says Atyab.

“POS machines cost $350-400, QR code costs only $1 dollar. If you include all the logistics cost, marketing cost, printing cost, it will cost $10 dollars for a single merchant. Whereas POS is $350-400 without the logistics cost or connectivity cost. The replacement cost of POS also runs much higher. In stark contrast, even if you have to replace the QR code 10 times because of wear and tear, it will still be $100 only,” says an industry expert.

It is an expensive endeavour for banks to deploy POS terminals while QR codes can be deployed at a much lower cost. For a merchant, the merchant discount rate (MDR) that merchant pays against the QR code, in case of POS is 2.5%, whereas in case of QR codes, the MDR is only 1% for international payment schemes. The merchant is naturally better off having a QR code rather than POS machines.

Because of its cost effectiveness, QR codes can be adopted by small merchants readily. Since majority merchants are small, QR codes become the most effective way to digitise payments on a large scale in Pakistan.

The status quo

There is a running theory in the industry that commercial banks are generally not inclined towards digital banking, and the only steps they have taken towards digital banking were taken because the regulator, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), directed these banks to do so. The theory makes sense. Banks want deposits. That is how they make most money and they are better off if the money stays in accounts at a bank.

“What banks don’t realise is that if someone pulls out cash, let’s say Rs5,000, from a bank, chances are that he will make some payments from that cash and some of it will remain in his pocket, and the banks are losing out on it,” one source explained. It seems to be a question of Pakistani banks being stuck in their old ways. “If the same customer is trained on digital banking and making QR transactions, the cash that remains in his pocket unused will stay in his account with the banks and banks would actually have more money in deposits overall if a majority is on digital banking. With digital, he would not need to withdraw Rs5,000. He will make Rs200 or 500 payments where it is required digitally and the remaining will stay with the bank and this will increase their deposits,” they add.

Our source also explained why banks are unable to think along the lines of digital banking and which keeps digital banking transactions, like QR payments, low. Officials that are heading digital banking divisions at some banks have spent decades in banking that has been done in an orthodox way. These people are also orthodox when it comes to banking with little understanding and consequently little inclination towards digital banking.

Our source adds that some of these officials are masters in core banking, but not digital banking, and are also unwilling to listen to people that are experts. We are talking about officials that are heads of branch banking business or loan business, the core of banking business so far, running the show at banks when it comes to digital banking and QR codes. “So you need new people in the industry who are experts of acquiring and issuing business. People who know how to onboard merchants for digital modes of payments, issuing digital payment instruments and the technicalities involved therein,” said one expert.

A source further said that technical know-how aside, some of the banks’ officials do not even promote their running digital banking products. “We are talking about a digital banking product that is enabled in mobile applications of some banks and bank officials are still not promoting it. It is all about prioritisation. If digital mobile payments are to be promoted, they have to make that the priority,” he adds.

This is coupled with the theory that the SBP is also laxed when it comes to enforcing penalties against digital banking, whereas they are active in imposing penalties when it comes to violation of branch banking rules. Lack of technical skills and lack of willingness to promote digital banking products, with lack of strict accountability has eventually resulted in the market being underserved.

Interoperability – the silver bullet

Before we try to understand what interoperability, you need to know the difference between an issuer and an acquirer. An issuer bank is the financial institution that gives you a debit card of a particular payment scheme. In case of QRs, an issuing bank is the financial institution with whom a customer maintains an account and uses its mobile application.

On the other hand, an acquiring bank is a financial institution that puts up a QR at a merchant location. It is similar to banks that put up POS machines at a merchant for debit or credit card transactions. So if HBL today is an acquirer for Visa, it would put up QR codes at merchants of the same payment scheme, that is Visa and all the banks that do issuance for Visa, meaning that mobile banking applications of these banks are enabled for scanning Visa QR codes, customer of all those banks will be able to scan and make payments through those QR codes.

Now, there are proprietary QR codes and non-proprietary QR codes. All the Visa, Mastercard or UnionPay QR codes are non-proprietary and any bank can do issuance or acquiring of those QR codes. The other option is that a bank creates a proprietary QR code unique to itself, meaning that only that particular bank would be an acquirer for that QR code and would put up those codes at a merchant itself (for non-proprietary codes, acquiring can be done by multiple banks). When it comes to issuance, only the bank’s customers will be able to make payments via those QR codes.

Basically, if you walk into a shop and see a QR code, you may have to look a little more clearly to see if it is a Visa and Mastercard QR code or a QR code from a specific bank. If the QR code is backed by Visa or Mastercard, its is non-proprietary, which means you can scan it with the bank app for any bank and make your payment. If the QR code has been issued for a specific bank, it is proprietary, and thus only the customers of that bank will be able to scan and pay.

Take EasyPaisa for example. The payments and branchless banking provider has both proprietary as well as non-proprietary QR codes. It has created its own QR code and it is an issuer for Mastercard as well. This means that as an acquirer, EasyPaisa would deploy its proprietary QR codes at merchant locations. It is an issuer as well, meaning that all the EasyPaisa users would be able to make payments through that QR code via EasyPaisa mobile application. Now since it is proprietary, no other bank customer would be able to scan and make payment using an app other than EasyPaisa on that proprietary code. This is what we call a closed loop transaction. It also brings up the massive problem of interoperability.

On the other hand, EasyPaisa does issuance for Mastercard that is a non-proprietary QR code because it is not specific to one bank only. So EasyPaisa customers can use their mobile application to make payments through a Mastercard QR code at let’s say McDonalds that has been put up there by a different bank, let’s say Bank Alfalah.

To summarise it again, a person with an EasyPaisa mobile application can make a QR payment on a Mastercard QR code placed by Bank Alfalah at McDonalds. But a Bank Alfalah mobile application user cannot scan a QR code and make payment at a merchant that has EasyPaisa’s proprietary QR code.

With different acquirers and issuers, different schemes and proprietary QR codes, it becomes a situation where there are multiple QR codes of Visa, Mastercard, Finja, EasyPaisa and JazzCash at a merchant. Seemingly, it is nice for a customer to have multiple QR codes and thus have multiple options and multiple incentives on QR codes to choose from, but only if he has those mobile banking applications. But it would be nicer if there is a single QR which could be scanned by all issuers, that is mobile applications of all banks, and the uptake and usage on QR codes would get better.

This is where 1Link and the SBP come in.

A quicker option to improve adoption of QR codes that the SBP recognised was to create an interoperable QR code, meaning each banks’ customer would be able to scan that code and make payments regardless of who put up the code. This interoperable QR code in Pakistan was created by 1Link, and it was called 1QR. It was created at the request of the State Bank of Pakistan between 2017-18, but between the years it was launched, 1QR has not been able to take off either and has gone bust.

“The problem with international payments schemes is that they can drive banks through incentives but do not have the power to mandate banks to partner with them. It ultimately becomes a time consuming process that a significant number of banks onboard with a payment scheme and enable large numbers of transactions on QR codes,” an expert in the fintech space, who chose to remain anonymous, told Profit. It is worth remembering that even with debit and credit cards, there was a process that took years for regulators to intervene and 1link to eventually connect all ATMs to all cards. Unfortunately, QR codes with their lack of popularity do not have that kind of time.

Whenever a scheme goes out and launches an interoperable QR code, they go out and promote that QR code heavily. For instance, Mastercard had designated marketing budgets for its QR codes to gain traction. But 1Link did not spend enough on marketing the interoperable QR against Visa, Mastercard and Unionpay QR codes that it would spend on marketing. “1Link had a window within which they had to go out and promote QR code and create the uptake but they are a company owned by 11 banks and that makes them completely ineffective,” says the expert.

“Only three to four banks agreed that they would become part of 1QR to create interoperability in the QR space, and there was no forceful implementation of this policy from the SBP. On the other hand, 1Link was competing with FonePay backed by Mastercard. They were putting up their QR codes and they were pumping in money into it. And because of that 1Link did not really get much traction on QR codes,” a source at 1Link told Profit.

“The 1QR code was in the market for a while. But when someone launches a card or a service like that, you have to go to banks and you have to integrate those banks and you have to run promotions and change behaviour. It is an expensive endeavour where these schemes when they issue these plastics and these QR codes create a lot of marketing programmes for players to sign up with QR code and merchants to put up QR codes. None of that took place in case of 1Link and consequently there has been very little uptake,” another source said.

Important players during this time that entered the QR space were mobile wallets JazzCash and EasyPaisa, which had closed loop models as described above. They stepped in because the business case was useful for them because they did not have debit cards initially and did not have anything to run their wallets for retail transactions. They only had phone applications for transfers and person to person (P2P) payment model. There was also increasing pressure from the SBP that P2P payments were in the grey and were hard to track.

Now, when EasyPaisa and JazzCash introduced proprietary QR codes, they put them up free of cost for the merchants. All of a sudden, EasyPaisa and JazzCash become competitive because of zero charges. Now with 1Link coming in with 1QR to create interoperability meant that 1Link was going to ask for a cut from EasyPaisa and JazzCash for acting as a switch to create interoperability. And paying 1Link that EasyPaisa and JazzCash would have to put some MDR on their QR codes which was free earlier.

Though 1Link proposed to EasyPaisa and JazzCash that they would only charge for a transaction that did not involve their proprietary QR codes. Meaning EasyPaisa users scanning EasyPaisa QR codes would stay in a closed loop. All other transactions would be made interoperable by 1Link and they would charge for that.

However, there was a problem with this plan. As our sources have informed us, these wallets, EasyPaisa particularly, had already made significant investments in deploying their proprietary QR codes, and that EasyPaisa had been very aggressive in trying to make inroads into multiple markets with QR codes backed by technical experts to make these investments a fruitful venture.

With 1QR, the investment was going to be diluted. And as it turned out that 1Link failed to promote interoperable QR codes also, it was reportedly these closed loop wallets that lobbied with the State Bank to remove 1QR codes where they had been deployed. As a consequence, the SBP had to do a tactical retreat because of which now there is no interoperable QR code in the market.

Even the payment schemes reportedly stood up and refused to use 1Link’s rail. “When the SBP said said that 1QR should be mandated, the payment schemes stood up and said that if 1Link’s rails are going to be used, payment schemes will pull their QRs from the market because their rails will not be used,” an official in the industry told Profit requesting anonymity.

Interoperability could have been achieved between payment schemes Visa, Mastercard and UnionPay. But payment schemes charge an MDR at 1% because they are foreign brands so why would 1QR be good for the industry? Because the MDR on it was even lower than international schemes. 1Link was only charging 0.3% in MDR to merchants against 1% charged by international schemes which would have been good for merchants for uptake of QR codes. 1Link, however, was not able to see it through.

But as the footprint of fintech companies increases, sources say that deliberations at SBP have promised these companies that interoperable QRs will be brought back to the market soon. The only problem is, and like a source tells us is that 1Link is “like a bank” because it is owned by 11 banks. Its governance structure makes it ineffective and inefficient. So let us hope that 1Link is not mandated to achieve the task of interoperability again.

Shahzaib

Can you please share the source for the numbers of merchants mentioned in the article?