Pakistani banks have been living large over the past few years. As the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) cranked up policy rates consistently, banks started riding a wave of record profits. The banking sector—both conventional and Islamic—has raked in some serious cash.

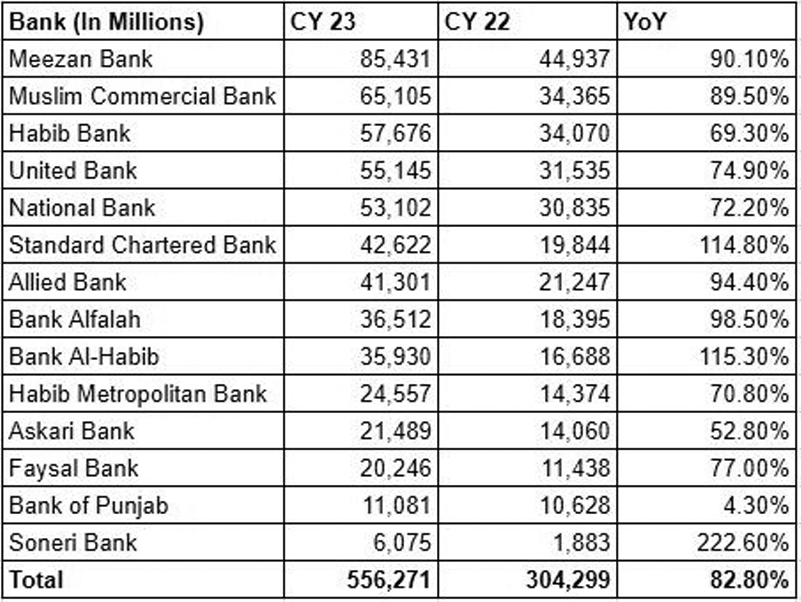

But a closer look shows that Islamic Banks made profits that were a bit larger than what you would expect them to have made in this time. Meezan Bank, for example, made the highest profit after tax in 2023. The bank was able to earn net profits of more than Rs 85 billion while the next best result saw MCB earn Rs. 65 billion. Next in line are the three biggest banks of the country with Habib Bank, UBL and National Bank of Pakistan earning around Rs 57 billion, Rs 55 billion and Rs 53 billion respectively.

This is even more intriguing considering banks like National Bank, Habib Bank and UBL have asset bases which are over Rs. 5 trillion, Rs. 4.6 trillion and Rs. 3 trillion, respectively. On the other hand, Meezan Bank has a smaller asset base of Rs. 2.5 trillion, yet it was able to yield almost double the profits compared to these behemoths.

Perhaps that is why the eye-catching profitability of the Islamic Banking Sector raised some eyebrows at a recent meeting of a Senate Standing Committee, which expressed its doubts about how Islamic Banks managed this. But before we get into that, it is worth revisiting how the banks have done so well in the past few years.

Sky-High Rates, Soaring Profits

Here’s how it all unfolded. Starting in September 2021, the SBP began aggressively hiking the policy rate. By June 2023, that rate shot up by a staggering 15%, peaking at 22%. The result? Banks posted record profits, with some nearly doubling their earnings. For example, Meezan Bank, the biggest player in Islamic finance in Pakistan, saw its profits after tax soar by 91% in 2023, hitting over Rs 85 billion. Meanwhile, Faysal Bank, another fully Islamic institution, wasn’t far behind, posting a 77% increase in profits.

The root of this windfall? High interest rates. But here’s the twist: instead of lending to businesses and consumers, banks are funneling their capital into government securities—a safer, less risky bet. This has left the private sector scrambling for credit, as borrowing costs have become prohibitively expensive.

It’s no surprise then that the government has started to take notice. On August 28, 2024, the Senate Standing Committee on Finance and Revenue took the SBP to task, calling for a detailed briefing on Islamic banking practices. The committee’s chairman, Saleem Mandviwalla, was quick to point fingers, accusing Islamic banks of exploiting consumers with sky-high rates.

SBP’s Deputy Governor, Dr. Inayat Hussain, pushed back. He contended that Islamic banking in Pakistan adheres to stricter standards than those seen globally, and that the accusations were misplaced. But is the government really just looking for a scapegoat, or is there more beneath the surface?

The Islamic Banking Boom

Pakistan’s Islamic banking sector is no small player. It began in 2001 with the goal of offering a Shariah-compliant alternative to conventional banking, and Meezan Bank received the country’s first Islamic banking license in 2002. Fast-forward to today, and Islamic banking has taken off. By the first quarter of 2024, 22 banks were involved in the sector, six of them fully Islamic. Together, they now command a 25% share of the market.

Meezan Bank has been leading the charge. Despite having a smaller asset base than conventional giants like National Bank, Habib Bank, and UBL, Meezan managed to deliver significantly higher profits in 2023. With Rs 85 billion in profit after tax, it outshined competitors with asset bases more than twice its size.

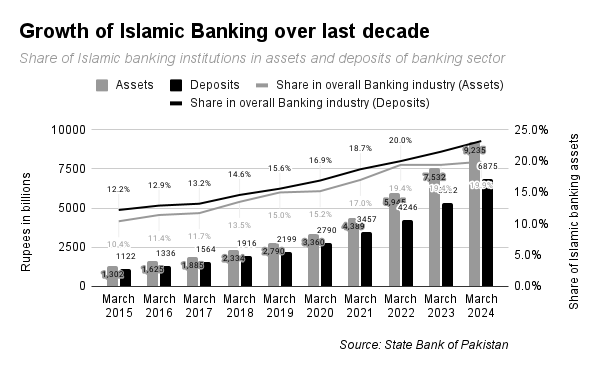

Between March 2015 and March 2024, the assets of Islamic banking institutions have, on average, grown by around 24% annually. Deposits with Islamic banking institutions have grown by around 22% during the same period.

Share of Islamic banking institutions in the overall banking sector has almost doubled. In 2015, the share of Islamic banking assets and deposits in the overall banking sector accounted for only 10% and 12%. This has changed a decade later with the share of assets and deposits doubling to almost 20% and 23% respectively.

Moreover, as mentioned earlier, amongst the banking sector, Meezan Bank made the highest profit after tax in 2023. The bank was able to earn net profits of more than Rs 85 billion while the next best result saw MCB earn Rs. 65 billion. Next in line are the three biggest banks of the country with Habib Bank, UBL and National Bank of Pakistan earning around Rs 57 billion, Rs 55 billion and Rs 53 billion respectively.

This is even more intriguing considering banks like National Bank, Habib Bank and UBL have asset bases which are over Rs. 5 trillion, Rs. 4.6 trillion and Rs. 3 trillion, respectively. On the other hand, Meezan Bank has a smaller asset base of Rs. 2.5 trillion, yet it was able to yield almost double the profits compared to these behemoths.

Perhaps it is this very contrasting profitability that caught the eye of the chairman senate and led to his inquiry into practices of Islamic banking.

Profit has already covered what has led to improved profitability for Meezan Bank and, in general, leads to enhanced profitability for Islamic banks.

So, What’s the Catch?

What’s driving this profitability? A big part of the story is the absence of a minimum deposit rate (MDR) for Islamic banks. Conventional banks, by contrast, are required to pay a minimum rate to depositors—usually 1.5% below the prevailing policy rate. So, with a policy rate of 17.5%, conventional banks are paying 16% interest on savings accounts. Islamic banks, however, aren’t bound by this rule. Instead, they follow a profit-and-loss sharing model, which results in much lower costs for the banks and fatter margins.

This lack of an MDR has created a larger spread for Islamic banks. While conventional banks saw their net spread (the difference between what they earn and what they pay out) shrink to 30% in 2023, Islamic banks held steady at around 50%.

The Real Difference Between Conventional and Islamic Banking

Islamic finance, by its very nature, works differently. It prohibits the charging of interest (riba) under Shariah law, so Islamic banks don’t engage in interest-based lending. Instead, they focus on risk-sharing. Depositors, in theory, are more like shareholders—if the bank profits, they profit; if the bank loses, they share in that loss.

On the lending side, Islamic banks often use asset-backed financing. A common structure is ijarah (leasing), where the bank buys a property and leases it to the customer, who makes payments that include a built-in profit margin for the bank.

In Islamic banking, savings and credit function differently from conventional banking. Islamic deposit accounts do not earn interest; instead, depositors receive dividends based on the bank’s overall profitability. If the bank profits, depositors share in the returns, but if the bank incurs losses, depositors may also bear a portion of those losses. This risk-sharing model aligns with the principles of Islamic finance.

In contrast, conventional banks are obligated to pay a minimum deposit rate (MDR) on savings accounts. This interest-based model ensures depositors receive a guaranteed return, irrespective of the bank’s performance, marking a clear distinction from the profit-and-loss sharing system in Islamic banking.

On the credit side, Islamic banks often use leasing (ijarah) as a financing tool. For example, the bank might buy a property and lease it to the customer over a fixed period, with payments structured to cover the bank’s costs plus profit. However, these payments are not labeled as interest, maintaining adherence to Shariah principles.

Exorbitant Rates or Fair Play?

So, are Islamic banks charging unreasonably high rates? It’s not a simple yes or no. A look at recent auctions of Shariah-compliant government securities tells a more nuanced story. Take the one-year Ijarah Sukuk, a bond-like instrument issued by the government. In July 2024, it was priced at 17.22%, which was actually 1.02% lower than the comparable one-year Treasury bill, which clocked in at 18.24%. The trend continued in subsequent auctions, with Sukuk consistently priced more competitively than conventional government debt.

For consumer products, too, Islamic banks are holding their own. The average profit rate on Islamic car financing hovers around 21.25%, which is roughly in line with conventional banks’ KIBOR + 4.5% rate. In housing finance, Islamic banks offer diminishing Musharaka (a shared ownership model), with an average profit rate of 20.56%, again aligning closely with market rates.

In some areas, Islamic banks are even leading the charge on competitive pricing. Since 2022, they’ve introduced fixed profit rates that undercut the current KIBOR regime by almost 3%.

On the consumer front, Islamic banks are increasingly gaining market share. An average Islamic car financing product offers an average profit rate of 21.25%, which aligns closely with the industry standard. Given that conventional banks have an average profit rate of around KIBOR + 4.5%, equivalent to approximately 21.5% with today’s KIBOR rates, Islamic banks are competitively priced. Additionally, Islamic banks have historically set benchmarks, with their lowest profit rate last year being 0.5% below the KIBOR rate, prompting other banks to adjust their rates accordingly.

In the Housing Finance sector, Islamic banks’ Diminishing Musharaka product maintains an average profit rate of 20.56%, consistent with industry rates. Furthermore, since 2022, Islamic banks have offered a unique fixed profit rate with an average of 15.75% across all segments, which is below the current KIBOR regime by nearly 3%. This competitive pricing has influenced other banks to adopt similar strategies.

It is important to note that Islamic banks are subject to rigorous oversight by their Shariah Compliance Departments, ensuring adherence to Islamic principles while maintaining international standards in other financial functions. This commitment to ethical practices and transparent pricing distinguishes Islamic banking and benefits customers by contributing to a more equitable financial landscape.

In contrast, higher rates are often observed in the domain of unsecured financing, a sector predominantly managed by conventional banks. Islamic banks offer limited unsecured financing products, which reflects a broader market trend rather than a specific issue with Islamic banking practices.

The competitive pricing of Sukuk, the successful participation in government and private sector funding, and the growing consumer confidence all contribute to a more nuanced understanding of Islamic banking practices. The rise of Islamic finance is driven not merely by religious adherence but also by its practical, asset-based investment model, which offers a competitive and increasingly mainstream alternative to conventional banking.

The Verdict: Ethical or Exploitative?

Islamic banks operate under strict oversight, with Shariah Compliance Departments ensuring that all practices adhere to Islamic principles. This focus on ethics is a big draw for many customers. However, with Islamic banks now competing head-to-head with their conventional counterparts in profitability, questions about fairness and transparency are surfacing.

Is Islamic banking truly a more ethical and consumer-friendly alternative, or are the banks simply cashing in on their unique market position? While their risk-sharing model and asset-backed approach offer some benefits, the absence of minimum deposit rates and government scrutiny are making people think twice. As the government continues its probe, the future of Islamic banking in Pakistan will depend on finding the right balance between profit and principles.