On May 1 this year, two pieces of legislation were bludgeoned through the Punjab Assembly that put out of commission a staggering 58,000 elected representatives in the province. Claiming it was the dawn of a new era for democracy in the country, the Pakistan Thereek i Insaaf (PTI) government rushed the Local Government Act, 2019, and the Village Panchayat and Neighbourhood Councils (VPNC) Act, 2019, through the provincial assembly on the insistence of Prime Minister Imran Khan. The Pakistan Muslim Leageue Nawaz (PML-N) called it a legislative coup.

Whether the move was heavy handed or prudent, the PTI was always going to take a stab at local body governments at some point or the other. After all, while the Prime Minister’s reformist credentials were put to the test in KP, his true battle ground, and the apple of his eye, was always going to be the Punjab.

That the Premiere is pulling all the punches is not strange or unexpected, After all, his party will still be licking its wounds after it failed to implement an ambitious local government plan in KP between 2013-18. Local government reforms have been on Imran Khan’s agenda from the early days of his much hyped 22 year political struggle. But the thing is, campaigning for local governments is not unique to Imran Khan. It’s just one of those things that everyone seems to support but still somehow never agree on.

For starters, the concept of having local government bodies instinctively makes sense. After all, it would be a more efficient administrative system and would add another tier to the democratic process, making accountability and access to said administrators a less arduous process than it currently is. It would also allow communities to look out for and administer themselves in accordance with their own best interests, and leave legislators in the assemblies to the more important task of actually legislating instead of being caught up in gali mohal riff raff.

But more than just being a third tier of democracy, having a local bodies system means having a new economic process. In essence, it is not just a new administrative stratification, but also involves the dispensation and spending of money. Things such as education and health that people automatically look towards the provincial government for would now be handled by local representatives.

This of course means big provincial and federal level politicians loosening their grip on the purse strings, and allowing money to flow directly into each district. In the Punjab, this would not only lead to the formation of small scale economies in every district but also creation of local conditions conducive for individuals and society to achieve better levels of economic development . It would mean different levels of performance and efficiency in the handling of money.

Then why is it that despite more than seven decades of existence, Pakistan continues to experiment with one local government system after the other? The answer is simple – money and politics. Local body governments can only be effective if they are empowered, otherwise they are toothless as a Duma. The key to an empowered local bodies system is funding, and that means the provincial government, specifically the MPAs that constitute it, letting go of the purse strings and agreeing to equitably split the spoils among the districts.

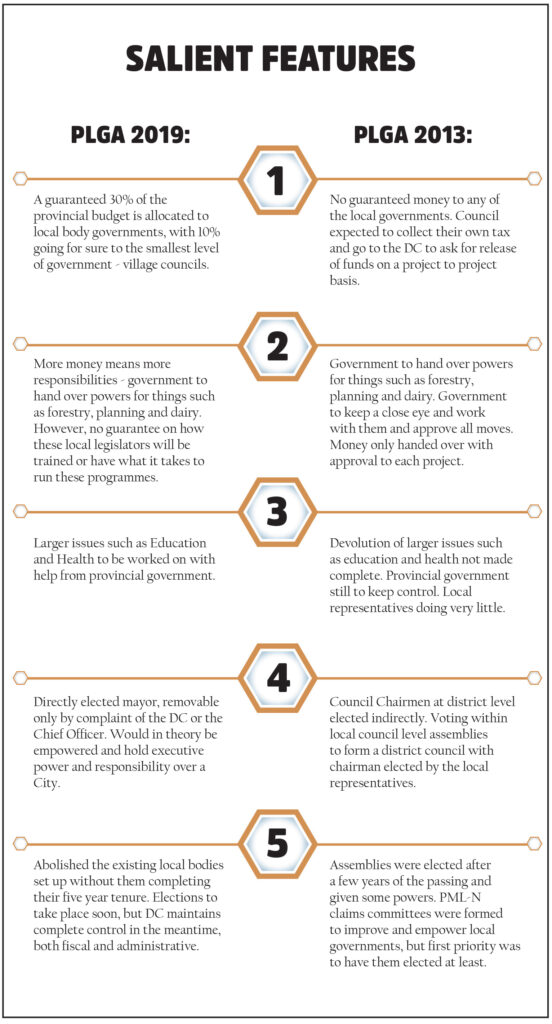

The PTI’s claim, for once, is a strong one. Though they may have taken the leap back in 2013, the PML-N’s local government system was far from empowered. District councils worked on a project to project basis, did not get regular funding, and were heavily dependent not only on the Deputy Commissioner (DC) of the district, but also how well connected they were to the local MNAs and MPAs. The current government has a bold new plan, one that provides smaller, more easily managed divisions. Their hook is a guaranteed 30% cut from the provincial budget to local governments.

One thing is clear, on paper, the PTI’s propositions are much better than what the League proposed and put in place. It distributes money not just more evenly to the districts and with a lot more checks and balances, it also distributes a whole lot more of it – and in turn dishes out many more responsibilities. The problem, however, is that in their aggressive blustering and posturing, the PTI has not allowed the (formerly) incumbent local representatives to complete their five year terms. And even after the passing of the Punjab Local Government Act 2019, the government will need at least a year, by their own estimates, to hold fresh elections, during which time districts will be ruled by the DCs – now without even the facade of some kind of local elected oversight to their actions. And with court cases already raging, the implementation of the new proposed system could be delayed until further notice. But the greatest concern keeping followers of the local bodies saga up at night is the KP analogy, where the PTI had also tried to implement a similarly groundbreaking local bodies system and failed miserably, with money not coming through and their own legislators standing as hurdles.

As things stand, there are currently no local representatives in the Punjab, and the DCs reign supreme – untouched and unmoved, waiting out the storm of the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) and letting their charges fester for now.

The PTI has undoubtedly made a bold move. But will it pay off? Politically, they have taken away the last bastion of remaining PML-N electoral authority in the province in one fell swoop. Financially, if implemented, their system could just be a stroke of genius. But the cost-benefit of the equation, at least as per the league, becomes a question of the democratic process and financial viability. And even if the PTI were somehow able to conduct elections within a year, their ability to implement this system and inject 30% of the provincial budget into district governments is what has everyone worried, especially since they have been keeping mum on the topic in recent times, as well as delaying the existing court cases against the PLGA 2019. How feasible is this plan? What are the implementation issues standing between the PTI and an empowered local body government? And what, if any, is the cost to democracy? Profit, takes a look.

The anatomy of a democracy

When the history books are written, one of the turning points in Pakistan will be the 18th amendment. In 2010 after the long years of the Musharraf era, the country finally seemed to be on a democratic track. And while the 18th amendment will always first and foremost be remembered for limiting the powers of the President and bringing Pakistan into a purely parliamentary form of democracy, it will also be remembered for bringing about the dissolution of certain powers from the center to the provinces.

When these powers were first being handed over to the provinces, Ahmad Iqbal was still an aspiring public policy maker with stars in his eyes waiting for a similar dissolution of powers to take place inside the provinces, and for local district level representatives to be empowered to tackle head on the specific issues of their localities. After all, once powers that should have been provincial from the beginning were finally handed over to the provinces, one would expect the provinces to follow suit and do the same on a district level. Article 140 A of the constitution brought in by the amendment said as much, legitimising local bodies as a necessary third tier of government. What happened instead was provincial governments taking control of what should have been local issues and forming bloated health, education and other departments.

Then, in 2013, the Punjab government led by the PML-N passed the PLGA of that year. For one reason or the other, elections could not be held until 2017. It was in this year that Ahmad Iqbal decided to pursue his interest in local bodies not as a policy maker, but as a candidate, being elected for council from Narrowal and going on to be nominated and elected as the council’s chair. Today, he is one of the 58,000 local representatives put out of commission by the Buzdar government.

Speaking to Profit at his home in Lahore, he has no illusions about the realities of the PML-N’s local body systems and the issues that came with it. He is a staunch League hand, among a crop of new leaders that were working their way up the party ranks and are currently reeling in the face of their party’s recent woes. But despite his fierce loyalties, he is candid about the realities of the system he was a part of. Mild mannered but well informed on the subject he has made his own, his main contention is that the PLGA 2019 is an unnecessary move – a case of thunder and no rain.

“There was absolutely no need for this,” he says. “This is little more than a change in nomenclature. If the government really wanted to empower local government’s, they simply would have funded the existing representatives.”

According to Ahmad, increasing the funding for local governments was simply a question of calling a meeting of the Punjab Finance Commission – the body consisting of provincial and local representatives as well technocrats that assigns funds from the provincial budget to districts.

“The biggest issue of local government is funding, and funding is not a function of legislation as the PTI is trying to make it out to be. We did not require this new experiment, and could have simply empowered the existing system” Ahmad explains. “If the PTI had really believed in local governments, they never would have sent elected representatives packing before their tenure was over. Instead, regardless of what party they belonged to, they would have backed and bankrolled them.”

“The reality, however, is that the PML-N had around 90% of the local representatives, and this new act coming in at such a time is not only suspect but is a simple rebranding” he goes on to say.

But while he thinks that the new system being introduced by the PTI is unnecessary, he is under no false pretenses regarding the issues with the system he was a part of until very recently. He admits that a number of the powers that the 2013 act had given to local governments were in fact retained by the provincial and were only shared in name. These included the larger fish like health and education, but even smaller issues such as forestry, livestock, dairy and development. Once again, to tackle these issues, the key was money – money and in turn power that the provincial government and its representatives were unwilling to give up.

“The PML-N government had already been looking into these issues. I was part of the empowerment committees, and there was a lot of drawing and redrawing we had to do because of legal issues, bureaucratic issues and other very technical issues – but we were determined to fix these problems” he explains.

“If the PTI wants to give 30 lakhs to every small council, I am the biggest supporter of this cause. But starting from scratch just sets us back and undoes so much work.”

Clearly Ahmad Iqbal believes in the concept of local governance – to hear him speak of it, it is the be all and end all of democracy and where the problem starts and ends. It is an attractive proposition after all – people elected directly for a small area that know the people and know the problems, empowered and financed with help from designated professionals is a dream combination to solve specific community issues in accordance with the wishes of the community. It also leaves the legislature to do what it is supposed to do – legislate.

This, of course, is the perfect local government scenario. Perhaps it is this belief and hope that drove Ahmad to take the Punjab government to court once the local bodies elected in 2017 were abolished. The case itself has not challenged the legality of the PLGA 2019, although doing this is also a distinct possibility according to lawyers. Instead, it is simply bringing up how elected assemblies could be so easily dismissed before their term ended, thus breaking the covenant between voter and state.

At the center of the League’s argument remains the single driving point: yes, their system was flawed, but they were working on it. The PTI acted rashly, and should have renovated not bulldozed.

But despite Ahmad’s claims that most of the changes are a what’s-in-a-name sort of situation, the PTI’s proposed system truly is leagues ahead of the League. But how exactly does it differ, and is it anything more than a pipe dream?

Revenues and expenditures

The cold hard truth is that the PTI’s plan is scrumptious – the sort of idealistic reforms that you just want to eat right up, lick your lips, and go back asking for seconds, and thirds. 30% of the budget goes to the local bodies, of this, a significant 10% to village councils and the remaining 15% to be divided amongst the districts. But despite just how good the deal sounds, the government doesn’t seem particularly keen to talk about it.

The mastermind behind the plan, of course, was the former Senior Minister Aleem Khan. Back in March, a couple of months before the Act was passed, he had been interviewed by this reporter for Pakistan Today.

The minister had seemed hopeful, promising major changes and to fight tooth and nail with his own colleagues in the assembly to take forward the vision of Imran Khan. Now, he shied away, perhaps because of his arrest by NAB and removal from office. Despite being back in the field, however, he first ignored messages on whatsapp and later deigned it beneath him to comment on his own designs.

Taking over from him had been the Law Minister Raja Basharat, but he too refused to comment, saying the local bodies charge had been taken away from him by the CM himself. Profit attempted to contact Chief Minister Buzdar, but to no avail, we are assuming because he may have been busy fighting the good fight, selflessly offering rides to people stuck in rainwater. Even his spokesman, Dr Shahbaz Gill, did not seem interested in being a person that speaks. But once again, he is a busy man with much on his schedule. While he did see our messages, perhaps he simply forgot to respond in the heat of making videos on the opulent nature of houses in the province.

The person that Profit was able to speak to was Dr Sameen Mohsin, an Assistant Professor at the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) who has been researching local governments in the Punjab since 2016 and has written extensively on the topic.

An expert at traversing the complicated geography of the PLGA 2019, she cautiously agreed with Ahmad Iqbal, saying that the PTI could have handled the situation with more care instead of taking the wrecking ball approach. But at the same time, she was clear that the system proposed by the PTI was a much superior one – the question once again remained one of implementation.

Ideally, local bodies would be expected to collect their own taxes – such as on property sales. But this amount is insignificant, and could also increase disparity between districts depending on what sort of infrastructure exists in and around them.

“In the PML-N system, taxes had been centralised, and local governments did not have control over them. They were also not getting the money they were supposed to” Dr Sameen explains. During the PML-N time, local governments were working on a project to project basis. They would apply to the DC for a grant for a certain project, and then it would be processed.

Of course, there are some confusions at this point. For example, getting approval from the DC seems to be an issue from the local government system that was set-up in the Musharraf era. And as Ahmad Iqbal explains, the local assemblies were empowered to make their own decisions during the League tenure.

“The house was empowered under the PML-N. They could approve projects, and the Chairman would have the executive powers to implement these plans. The DC had no function in this system” he tells us.

But as he goes on to explain, the DC was simply looking after revenues, which were a provincial matter in the PLGA 2013. They were also an ad hoc sort of administrative authority over health and education – two departments that were still in the process of being devolved.

However, the one thing that the PTI still has going in its favour, at least so far as the legislation itself is concerned, is the amount of money they are promising the local bodies.

“In the new system, the government is pledging 26% from the budget for the first year to local governments. This amount is fixed, and can go up but not down. Of this, 10% goes to the village panchayat councils and the rest to the districts” says Dr Sameen.

“In theory this money should be divided equally, but the Provincial Finance Commission (PFC) also has a role to play over here, and if it determines that, say, Faisalabad should get more money on so and so indicators – that would be the call of the commission.”

While Profit was unable to get the government to comment on this, even though up until this point their plan seemed impressive, Dr Mohsin was kind enough to share some of her conversations with the former secretary who had drafted the 2019 legislation.

According to him, and in turn the PTI, the PFC was not there to meddle, but a safeguard to ensure that not only was the budget being allocated, but that all areas were being treated equitably rather than equally. The argument is sound, after all, some areas might be able to raise their own money through taxes because of say, them being important points near the motorway. Other more isolated areas might thus need help, and a mixed PFC with provincial and local representatives as well as technocrats could possibly keep things in balance.

In essence, the PTI government has handed over a lot more revenue to the local bodies. Not only this, but instead of approving project to project, they are also empowering the councils by giving them a free reign. But what this ends up doing is also making local governments responsible for a lot of their own expenditures, and thus putting a lot more responsibility on their shoulders – with apparently little thought given to any training that these political novices might require.

This, of course, is a concern. But one that is easily brushed away by the PTI since they have always branded themselves as an idealistic party. While one may worry about the lack of experience and training of local representatives with handling this much money and dealing with this issue, the PTI has time and again said that this is their method to build up Pakistan’s future leadership. It is a question of trusting the people of Pakistan, and a difference on a more ideological and fundamental level than it is a technical one.

The provincial government would thus no longer have to worry about things such as zoning, waste management, forestry or dairy. They would simply hand over the money, and the local government would do with it as it thinks best. Even education and health would ideally fall under the local government category, but because of the complicated nature of such departments, the powers here will be shared – with an aim to eventually devolve these to district government’s as well.

“This time there is a lot more responsibility. The third schedule of the act explains the functions – things like education and health in part 1 are to be done in coordination with the provincial govt, which basically means by the provincial government. Part 2 is the sole domain of the local govt. Once money has been transferred, the expectation will be higher” Sameen Mohsin explains.

But despite all these new responsibilities, and their idealism, the PTI has maintained one major check on the powers and freedom of these legislators, and a dangerous one at that: the bureaucracy.

Azeem ush shaan Shahenshah

While the revenue-expenditure model being proposed by the PTI captures a pretty picture, one of empowered local governments with funds at its disposal, there remain certain structural issues, that may just have become even more pronounced than they were in the previous system that the PML-N had brought in.

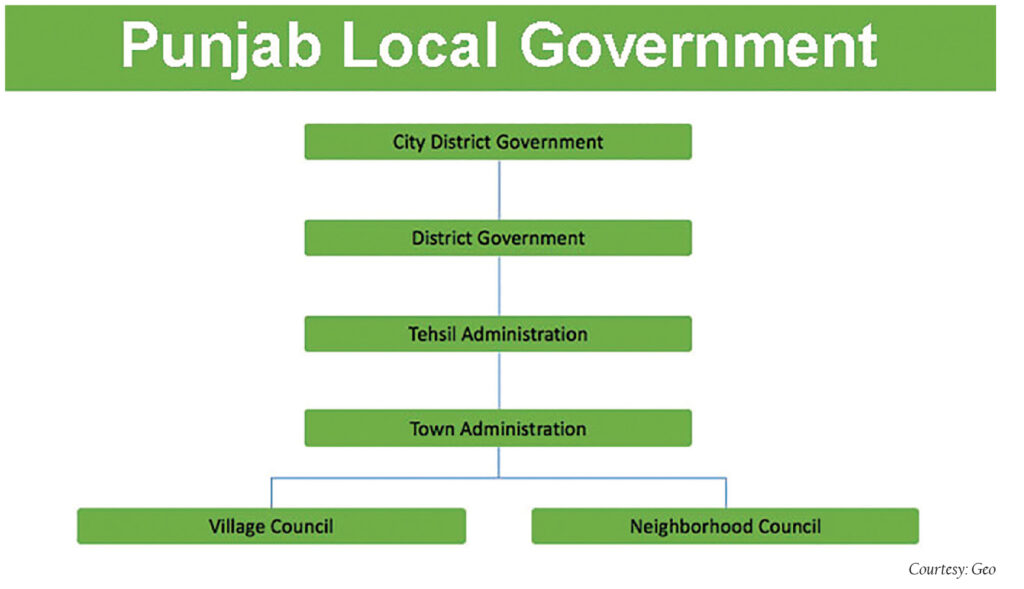

Enter the DC, the MPA, and the Chief Officer. The DC and the MPA are household terms – princely figures in local politics and the distribution of money. But what the PTI’s plan introduces is the concept of a Chief Officer, a figure now verging on the Kingly in his district. You see, in the new system, the PTI has argued that a district is too large to be run by a single body efficiently, so the largest division in the new local bodies system will be a Tehsil.

“You see they’ve place local governments in a very awkward position by not having a district head. You would automatically think that this would mean we’re doing away with the position of DC, but instead they’ve only given them even more power” says Ahmad Iqbal.

And he’s right. Other than the DC having the power to decline moves made by the local government, there will also be a new position called ‘Chief Officer.’ This bureaucrat will be responsible for coordinating between tehsils, and be the de facto and de jure head of the district.

“The people of Gujranwala are the real stakeholders of Gujranwala. The DC of Gujranwala is no one. This is a transient office, and it cannot be allowed to rule the roost” Ahmad continues.

Sameen agrees that this is a lapse, and could in fact be used by the government to control districts in case of inadvertent results in local body elections.

“The CO has a lot of power. He is basically responsible for everything. Is there going to be a meeting? The CO will be in charge. Paperwork? The CO needs to sign off on it. In turn, the DCO is going to want to be cosy with this new officer, and local government representatives without much political clout will be left without the influence that their mandate should grant them” she explains.

An example she cites is that of Saira Afzal Tarar, an MNA from Hafizabad whose father was the District Chairman in the city. Because of this close relationship, the DC would listen to Ms Tarar’s father and approve his projects. If a young, unconnected up and comer was to become District Chairman, they would not be able to move paper and get things done as effectively.

As the then secretary in charge of the Act had explained, however, the Act introduced checks and balances onto the role of the bureaucracy. It makes sure that the bureaucracy is answerable to elected representatives as much as they are accountable to bureaucrats. This, however, might raise the possibility of deadlocks on key matters of spending.

“Financially speaking, this Act introduces checks in balances. It requires audits and oversight by the finance commission. But at the same time, these local councils will not be able to pull any of this off without the help of the DC since they are untrained. And if the government wants to use its officers nefariously, then nothing will stop it” she said.

However, another concern expressed by Sameen was an interesting one – that with so much power in the hands of the COs and DCs – development would essentially be paralysed, because none of these officers would be willing to sign anything.

“Even if the PTI is somehow able to implement this, these bureaucrats still have a lot of power. This means that nothing can happen without them. And if the current process of accountability goes on as it is, then no one will be willing to sign anything as it has been happening in recent times. No bureaucrat wants to risk the wrath of NAB.”

One way that the PTI had been planning to circumvent this issue was through a directly elected, and empowered Mayor in certain larger districts. To his credit, Ahmad Iqbal said he supported the idea of direct elections as a democrat, but questioned the timing and feasibility of such a move.

“As a democrat it makes sense to me, but this would also mean that only people with money can run for mayor. In the PML-N’s system, any councilor could be elected to this executive position” he says.

“This topic had been brought up in the Musharraf era as well, but all the parties had agreed that it would be too much. For example, one of the issues was that the Mayor of Lahore would end up having a larger electoral mandate than the Prime Minister of Pakistan.”

Despite the complexities of such a plan, Dr Sameen continues to think that it might in fact just be a good idea. “Direct election means there is one person solely in charge of all of the urban concerns of Lahore – and if that person is an empowered mayor like say they have in London or Istanbul, then they have the capacity to make great changes and be a major player in politics. I don’t think mandate is a reason to not have a directly elected mayor. And the benefit is that direct elections mean direct accountability.”

While the two have some differences on the issue of directly elected mayors, the point they seem to be missing is that as per the 2019 Act – while the mayor wields significant financial powers, the DC can still refuse him. In fact, if the mayor is unable to explain himself before the DC, the DC can move the provincial government for the removal of the mayor – a one man, bureaucratic impeachment.

In the PTI’s defense, the Mayor and the council can also have the DC or the CO investigated if they find enough cause. Accountability in this system works both ways, but considering how Pakistan works, the system still leaves some room or the other for there to be political pressure exerted through the bureaucracy – if it isn’t paralysed by the crippling fear of accountability watchdogs of course.

But the organisation aside, there is one other fear: that the PTI will simply not do any of what they have promised, and that the DCs will continue their lazy reign of not signing anything. And that is where KP comes in, and the disaster that the PTI’s local government reform efforts were in that province.

The KP story

It was a trainwreck. It was a dumpster fire. It was a trainwreck inside a dumpster fire. The PTI has tried many things in KP that have been disastrous – the BRT project comes to mind for example. But the much touted local government reforms are where they really did outdo themselves.

“They simply just didn’t hand out the money they were supposed to” explains Muhammad Saleem, a KP based developmental economist. “In KP they also promised a 30% cut of the budget to local governments, but when the time came, they just didn’t hand out the money.”

Education was supposed to devolve completely to the local tier of government, but instead it became one of the most powerful and boasted about ministries in the provincial government. Similarly, there was a finance commission in KP as well, but without any money to allocate, their annual meetings became little more than catch ups over tea.

As a number of local government representatives explained, their election had increased their social standing, but without any money at their disposal, they were unable to do anything.

“The conspiracy behind this, so to speak, of course was the PTI’s own MNAs and MPAs. You see the local MPA was basically playing the role of the DC here, and these legislators did not want to give up control of the money and discreatonary funds, so they just didn’t let it happen” explains Muhammad Saleem.

Along with this, the local governments were unable to collect any taxes even, since even this bare basic operation required money that they did not have. In addition to this, property that they owned in Swabi for example, was the cheapest in the area and went practically for peanuts.

Back in March when Pakistan Today had interviewed Aleem Khan, he had admitted that the biggest task would be reigning in the party’s own MPAs, who were already feeling disenfranchised by the empowerment of local bodies. While Profit had been able to get some answers from here and there representing the PTI’s defenses of the possible problems in their act, this is one question no one was interested in answering. Whether this refusal to speak on the matter now indicates that fear becoming a real problem or not is for the PTI to answer – but it is certainly a possibility.

The verdict

At the end of all of this, despite the drawbacks and the PTI’s plan having the fail safe of bureaucratic oversight, the PLGA 2019 still sounds like a dream plan. The sheer amount of money being promised to the lowest tiers of government along with the authority to spend it is inspiring. But will they ever get the money? And if someone other than the PTI is elected and in charge, will the CO ever let them use that money if they actually get it?

The possibilities are endless, but then again, so are the pitfalls. The current reality, however, is that there are no local bodies in Punjab. And as things stand – the DC rules in seclusion, trying their best to keep away from the long reaching claws of accountability. While Ahmad Iqbal has not challenged the legality of the PLGA 2019, it is only a matter of time before that happens, and judges are quick to grant stays.

The PTI must remember, they are in power only for five years unless re-elected. If they are unable to fight the court battles or arrange elections, the DCs could go on ruling in their self induced stupor. They would not suffer. The PTI would not suffer. Even the League wouldn’t. Just the districts. And until third tier representation is ensured, Article 140 A of the constitution via the 18th Amendment remains unfulfilled, and Punjab remains in the grips of a colonial administration system. The money remains undisturbed, and the functions are unmoved.

Perhaps Ahmad Iqbal is right. Flawed as the PML-N system was, perhaps it was hasty to dismiss it completely instead of giving it the heavy reforms it quite clearly required. Money could have been injected into it rather than spent on something shiny and new.

You never know, of course, the PTI might just have a few tricks up its sleeve. But looking at KP, and looking at the facts, one shudders to think of all that could go wrong.

The (VPNC) Act 2019 should be implemented with major focus on Karachi, which would bring discipline, legitimacy.

We are always with our PM in his every step that he taken for the betterment of Pakistan

Comments are closed.