If there is a single place that can be thought of as the foremost cathedral to free-market capitalism, it is not the New York Stock Exchange, nor any other place in Lower Manhattan, or the City of London; it is Saieh Hall at the University of Chicago in the historic Hyde Park neighbourhood on the south side of Chicago. Fitting, perhaps, then that the building was originally built as a theological seminary and has a decidedly religious architecture. In this building is housed the University of Chicago’s economics department, which has produced or otherwise been affiliated with 29 Nobel laureates in economics – more than any other institution in the world.

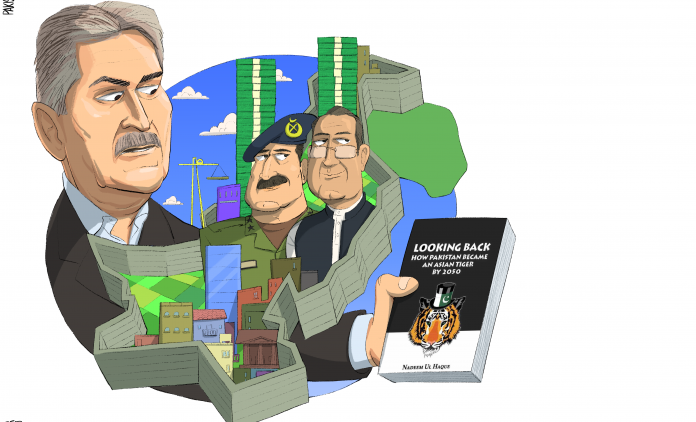

It is here that Nadeem ul Haque, former head of the Planning Commission and author of Looking Back: How Pakistan Became an Asian Tiger by 2050, got his training as an economist. It is not possible to understand his work – arguably one of the very few forward-looking visions for economic growth for Pakistan put out in recent years by a trained economist – without understanding where he comes from.

Say the name Nadeem ul Haque in front of any bureaucrat or journalist in Islamabad (or really anywhere else in Pakistan), and you will get the same look. That smirk, coupled with a rolling of the eyes. A knowing look of the cognoscenti. “Oh, that doddering fool. Yes, of course we know of him. He has no idea what he is talking about. All he has are theories from America. We know how the real world works, especially in Pakistan.” And in some ways, they are right.

Haque is a man obsessed with ideas in a country where – by his own acknowledgement – there are very few readers even among the literate and educated segments of the population. And while he has documented the ways in which the civilian bureaucracy maintains its stranglehold on Pakistan’s economic resources perhaps better than anyone else, he never quite managed to find a way to thwart their control. To use an analogy from the 1980s British political satire Yes, Minister, it would be as though the minister Jim Hacker understood exactly what his top bureaucrat Sir Humphrey Appleby was about to do, but did not know how to stop him.

Yet despite these appearances of being a misfit in the government of Pakistan, Haque – through his papers and now this book – has diagnosed the fundamental disease of Pakistan’s lack of economic growth and progress quite well: the charge of moving the country’s economy forward has been given to an institution (the Civil Service of Pakistan) that is far more interested in maximizing their own gains and that they do so specifically through their control of urban geography, in particular through their control of the country’s prime real estate.

Looking Back is a quick read (I finished it on a six-hour flight) and covers a wide range of subjects (more on the book’s unique storytelling mechanism later), but is most persuasive when it lays out its case on exactly how land is used as the ultimate economic resource in Pakistan. Control of prime real estate is used to not only enrich the higher echelons of the civilian and military bureaucracy, but even within that bureaucracy, to provide greater benefit to those who toe the line more to the Establishment (in the broadest sense of the word) than those who are seen as less subservient.

Say all you want about Haque’s theories, this diagnosis of the primary ills of Pakistan is hard to argue with. How did this supposedly out-of-touch Chicago-trained career-IMF economist come to so clearly understand and diagnose the travails of Pakistan’s bureaucracy? Well, it helps that he grew up among them.

A privileged upbringing, a flirtation with Marxism, and Chicago

Nadeem ul Haque was born in 1952 to S.I. Haque, a very well-known civil servant of the time and a member of the old British-era Indian Civil Service (ICS) who went on to become the last chief secretary of West Pakistan. It is unsurprising then, that he went to Aitchison College and Government College Lahore before jetting off to London in 1971 to begin an undergraduate degree in economics at the London School of Economics.

Perhaps most shocking for a man who would later go on to study in Chicago around the likes of right-of-center icons such as Milton Friedman was his very serious inclinations towards Marxism. Sitting in the living room of his house in the suburbs of Washington DC – the fruits of a lifelong career at the International Monetary Fund – I asked him what on earth he was thinking when he decided to become a Marxist.

“You don’t understand. It was the peak of socialism back then. Marxism had hope and promise. The United States was embroiled in the Vietnam War. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union was showing tremendous technological promise.”

And Haque was not just a campus Marxist either. He was one of a band of roughly a dozen Aitchisonian boys – privileged lads, all – who decided to take their ideas about a Marxist utopia to Pakistan and fight alongside Baloch separatists in the insurgency in early 1970s. These boys included Najam Sethi, Ahmed Rashid, and a few others. It appears that the nerdiest, and least capable of fighting, was Haque (though most accounts suggest that the others were not much better either).

The Aitchisonian alumni in the Baloch insurgency, however, were not seeking to actually support the separatist cause. They were trying to persuade the Baloch to become the vanguard of a Marxist revolution that would encompass all of Pakistan. In other words, they wanted the Baloch militants to be revolutionary and Marxist, but not separatist.

Haque was arrested before he had a chance to do anything and spent a night in jail before being bailed out by Najam Sethi, who vouched to the government as to just how truly useless a militant Haque was.

The youthful indiscretions notwithstanding, Haque spent the next few years working at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), working alongside professors who had never studied what was then still the relatively new subfield of econometrics, the now standard quantitative side of economics. He was always an academic at heart and after a few false starts, finally managed to land a slot at the University of Chicago’s PhD program in economics, where he started in 1979.

At Chicago, Haque went from being surrounded by people who barely knew what a regression was to being surrounded by Nobel-prize-winning economists who expected him, a humble graduate student, to critique their work. His thesis advisor was Gary Becker, the man who practically invented the concept of human capital as a theory in economics (he would go on to win a Nobel Prize in economics in 1992).

“They killed my confidence in Pakistan,” he said. “And there I was in Chicago, having Becker and Heckman [both Nobel laureates] asking me to critique their papers. I would go into the standard Pakistani mode of deference to them. Becker looked at me point-blank and said: ‘This is not you being impolite. This is your job. You are supposed to critique my work.’ Papers of mine that were rejected at PIDE were picked by Heckman for me to deliver seminars on at Chicago.”

That serious training in economics – alongside giants in the field – laid the intellectual foundation of Haque’s career. Although he spent the next 30 years at the IMF, his mind kept working on the most fundamental question that should plague any Pakistani economist: why has Pakistan lagged behind so many of its peers in Asia, and what is stopping it from attaining the kind of economic growth that would create a truly broad-based prosperity in the country?

Looking back: the narrative tool

Rather than the standard, dry economics texts where the writer simply expounds their views on what ails Pakistan (I’m looking at you, Shahid Javed Burki), Haque tries a different approach. He imagines a prosperous Pakistan at a point distant enough in the future (he picked 2050), and then works his way backwards as to how he imagines Pakistan could get there. In this, it is a fundamentally more optimistic view of Pakistan, laying out a vision of what the national interest should look like, and then tries to imagine a path the country could take to get there.

Haque is the first to acknowledge that the path he lays out is by no means the only right one. Indeed, in the preface to his book, he states that his purpose in writing it is to encourage a conversation among Pakistanis as to what they think is the optimal path to getting there.

In Haque’s imagination, the key to solving Pakistan’s problem lies not a single theoretical model, but rather in viewing Pakistani society, politics, and its economy as an interwoven complex system that has its own dynamics and is best shaped by fostering a bottom-up ideas-led approach to solving local problems that then work their way up throughout the entire complex system.

Yet while his ideas about what might allow Pakistan to move onto the path of becoming an economically prosperous, politically peaceful, and socially vibrant country are interesting, the most well-developed parts of his book are those where he tries to diagnose the problem. And the fundamental problem – he argues – is that the government of Pakistan is a badly designed institution that is geared to serve the interests of its elite members, not of the country as a whole. While he cites many areas where this system of perverse incentives manifests itself, a theme that runs through much of the book is the manner in which civil servants control land and how they use that control to enrich themselves at the expense of the nation as a whole.

Land: Pakistan’s biggest Ponzi scheme

Any international investor who has analysed Pakistani real estate will tell you that the market makes no sense whatsoever. Rental yields are abysmally low, mortgage financing virtually nonexistent, and yet somehow property prices are astronomically high. There are now several buildings in Karachi and Lahore with $1 million asking prices for apartments. How does this make sense? Who can afford these places and how are they paying for them, if not through a mortgage?

To understand the absurdity of Pakistani real estate, one must first look at what constitutes prime land, how it is zoned, how it is used, and thus how its relative scarcity determines its prices. And in this, it helps to understand how the government – specifically, its top decision-makers – think about land.

Drive through any major thoroughfare in any city in Pakistan and one finds the vast majority of the real estate there occupied by government buildings. Not public institutions accessible to the public at large, mind you. No, these are buildings built by the bureaucratic elite to serve the bureaucratic elite. Close to these buildings are large suburban-style developments meant originally for government officials. These developments have the best infrastructure Pakistan has to offer, and proximity to the heart of the cities they are located in, and they are given away at throwaway prices to the elite of the civilian and military bureaucracy.

Instead of developing dense cores around which to center economic and social life, Pakistani cities have central districts designed to create generational wealth for bureaucrats. (Disclosure: I am personally the beneficiary of this unjust socio-economic order. My father is a retired military officer who sold one of the plots he received after retirement to pay for my undergraduate education at a university in the United States, an educational experience that has fundamentally transformed my life, and significantly enhanced my lifetime earning potential. Yes, you absolutely should hate me, and people like me.)

But even if one were to ignore the grand larceny that are the plots and perks that bureaucrats award themselves, the economic costs of using prime land for residential rather than commercial purposes makes no sense. The Planning Commission and the Capital Development Authority estimated in 2011 that Islamabad alone had 60 million square feet of land dedicated to awarding perks to civil servants which, if commercially developed could result in Pakistan’s entire GDP being raised by 2-3%. And that is just Islamabad. Cities all over Pakistan have this kind of prime real estate being wasted.

But Haque goes beyond just pointing out such waste. His central argument is that the government does not work for ordinary Pakistanis because it has set up a perfect system to maximise wealth for its own senior members and to ensure that there is no internal dissent within the civil service.

Junior civil servants run local governments, mid-level bureaucrats run the provinces, and the senior-most babus run the federal government. At each level, the bureaucrats are paid very little, but given access to homes, cars, and servants, the kind of luxuries one would expect to be able to afford only in the later stages of a highly successful career in the private sector.

At each level, bureaucrats are charged with decisions on where to allocate government resources, and how to allow private resources to be allocated across urban Pakistan. And at every level, bureaucrats are reminded that while they may be living large, they are cash poor, a situation that will only be remedied upon retirement, or close to retirement, when they get their plots of land and houses to build on them.

Given the fact that their whole life’s financial success (assuming they are the most honest officers imaginable and do not take any bribes at all) depends on the value of the land they will get upon retirement, what kind of decisions do you think they will make about public policy?

Where will the roads get repaired faster? Which neighbourhoods will get the heavier police presence and better security? Which neighbourhoods will get allocations of land for schools and hospitals? Where will the street lights be functioning? And conversely, which neighbourhoods will these supposedly noble civil servants not care about? The answers, based on their incentive structures, are obvious.

That, in a nutshell, argues Haque, is Pakistan’s problem. Resources are allocated to pad the retirement benefits of the bureaucracy, not to create a vibrant society and dynamic economy. No set of policies, no matter how well designed, will work to fix Pakistan’s woes unless the government charged with implementing those policies has its incentives shifted away from serving themselves and towards serving the nation as a whole.

On this, he is scathingly critical of bilateral and multilateral donors and their consultants who make painstaking efforts to analyse various sectors of Pakistan’s economy and develop policy recommendations, which are then adopted wholesale by the bureaucracy, because it relieves them of the burden of having to do any thinking for themselves. Haque’s biggest criticism: that donors design policies and proposals without examining the ability or willingness of the bureaucracy to implement them. Crucially, no donor appears willing to even touch the subject of civil service reform.

In his book, Haque argues that one way to significantly improve the functioning of the government is to adopt what is fundamentally the Singapore/Japan model: high salaries, with very few fringe benefits, which forces bureaucrats to think about the infrastructure of the country as a whole, not just the specific colony in which they plan to retire.

Whether Haque is being optimistic in expecting the civil service to give up their luxurious benefits, or whether he has a realistic plan, remains an open question. One key piece of evidence? His proposals for civil service reform, which he put forward in 2011, went absolutely nowhere.

Wonderful read Farooq. I’m definitely getting this book.

This book has disclosed real character of civil servants who never worked 4 poor people of Pakistan.the whole establishment mint the wealth thr real estate. Dr Haque one must read.very informative & investgative book from economic as well as politcal point of view i want 2 read this book.

The article is more concerned about Nadeem ul Haque rather than about what he has said.

You have established his authority lets move on…