It was March 16, 2008 and I walked into my office at 9 am just like I had done for the past two months. I was an entry-level research analyst at a small brokerage firm in New York, my first job. My office was in Midtown Manhattan, specifically at 380 Madison Avenue, just two blocks up from the Roosevelt Hotel, owned by Pakistan International Airlines. Across the street from my office was 383 Madison Avenue, a large octagonal building of stone, glass, and steel that was the global headquarters of Bear Stearns.

This day, however, was different. For starters, within a matter of minutes, all of my colleagues seemed to be congregated around the windows overlooking Madison Avenue. And so I joined them. What I saw was a sight I had never seen before and will never forget: thousands upon thousands of employees of Bear Stearns, the venerated American investment bank and the fifth largest in the world, were pouring out of the building and onto the street, many with boxes that contained what appeared to be the entire contents of their desks.

It was starting.

The global financial crisis which would go on to transform the world as we knew it was unfolding right before my eyes, though at the time I had no idea of the significance of what I was witnessing.

At lunch that day, the high-end restaurants in the neighbourhood that normally catered to the high-flying investment bankers and traders were completely empty. The McDonald’s and the low-priced delis, however, were packed with people who just a few days ago would have scoffed at the idea of having to eat there.

At the close of that day, we found out that Bear Stearns would be sold to JPMorgan Chase, for just $2 a share. It was a humiliating end to an investment bank that had once proudly proclaimed that it was the only Wall Street firm to have remained profitable throughout the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Six months later, the same drama unfolded, this time at Lehman Brothers. This time, of course, the reverberations would be a lot louder. Lehman was much bigger than Bear Stearns, and unlike Bear, Lehman was not bought out but filed for bankruptcy. The fallout was much worse.

In November 2008, I moved back to Pakistan (no, I wasn’t fired or laid off) and began working at the asset management subsidiary of Faysal Bank. There, I found that a financial crisis similar to the one that I had experienced in New York was also playing out in Karachi.

However, it had very different origins, and would end very differently as well.

Unlike the US financial crisis of 2008, which started in the private sector, the Pakistani financial crisis that year started in the public sector, and was motivated largely by the desire of the Musharraf Administration and the then-ruling Pakistan Muslim League Quaid (PML-Q) to win the February 2008 elections.

In its bid to win that election, the Musharraf Administration decided to try to hold petrol prices in Pakistan artificially low at a time when oil and commodity prices were rising sharply throughout the world. In late 2007 and early 2008, the government ended up spending the country’s foreign exchange reserves in order to do so, leaving the country with both a massive fiscal deficit as well as a current account deficit.

By March 2008, when the new government – led by the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) – came into office, the fiscal deficit was well on its way to above 7.5% of the total size of the economy and the current account deficit was even higher at 8.5% of gross domestic product (GDP). The impact on the country’s foreign exchange reserves was particularly dire: before the crisis started in late 2007, Pakistan had $16 billion in foreign exchange reserves. A year later, that number was down to less than $5 billion.

When the new government took office, it began correcting many of the catastrophic errors that had been committed by the Musharraf Administration. However, the situation could not be fixed without significant pain inflicted not just upon the country’s financial system but also the wider economy.

For starters, the rupee had to be allowed to fall from the artificially strong levels it had been kept at by the previous government. That had two effects: it caused a sharp rise in inflation – and therefore interest rates – and it caused many wealthier individuals to begin pulling out money from their rupee accounts, and converting them into dollars, further exacerbating the slide of the rupee.

This hit the banks on two fronts. At one level, the rise in inflation and interest rates meant that their loans (the asset side of their balance sheets) started to go bad as more and more borrowers struggled to make the now much higher interest payments on their loans. On the liability side of their balance sheet, the movement of deposits out of rupee accounts meant that there was a crunch of liquidity right when they needed the money the most.

And then were the rumours.

There were several rumours doing the rounds that – just like in 1998 after the nuclear tests – the government might freeze assets and might even go further and actually seize the contents of bank lockers and vaults.

It also did not help that in the middle of all of this came Eid ul Fitr (which was October 3 that year), which is when banks traditionally have a hard time because so many people withdraw large sums of money from their accounts to spend on their family and for Eidi.

The situation got so bad that the interbank lending market – the market in which all commercial banks in the country lend money to each other to make up for short-term asset-liability mismatches, and one that is the lifeblood of any country’s financial system – seized up. According to sources who worked in the treasury departments of those banks at the time, and wish to remain anonymous, the situation did not just affect the small banks. At one point, around Eid ul Fitr, the market was so frozen that treasurers from Habib Bank and United Bank were unwilling to lend to each other.

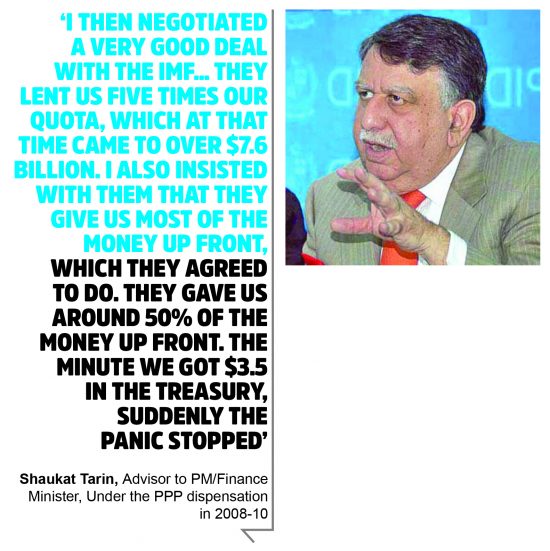

It was in the midst of all of this – on October 8 2008 – that Shaukat Tarin, a legendary figure in Pakistan’s banking community, was appointed federal finance minister and told to stave off one of the worst financial crises the country had seen up until that point.

“I took over in October in the middle of a severe liquidity crisis and I thought that Pakistan would not have enough money to pay off its bonds that were maturing in December 2008 and January 2009,” said Tarin, in an interview with Profit. “We had less than one month’s reserves. The current account deficit was $2.5 billion a month! I knew that in about two months, we could go bankrupt.”

The global financial crisis was not directly affecting Pakistan, but it was making solutions much harder to find.

“Because Pakistan’s economy – particularly the private sector and the banks – are not that well-connected with the global economy, the Lehman crisis did not hit us that much,” said Tarin. “But because the global bond markets were frozen, and because our export markets were very weak, we had to rely on extraordinary measures.”

The first thing Tarin did was try to stem the domestic panic. In a meeting he chaired at the finance ministry, he declared “over my dead body will anyone consider asset seizures” in Pakistani banks. He then went on television and addressed head on the rumours that were causing a run on the country’s banking system.

And then, over the objections of President Asif Ali Zardari and Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani, Tarin headed to Washington to negotiate with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a bailout that might help stop the bleeding.

“I then negotiated a very good deal with the IMF,” said Tarin. “They lent us five times our quota, which at that time came to over $7.6 billion. I also insisted with them that they give us most of the money up front, which they agreed to do. They gave us around 50% of the money up front. The minute we got $3.5 in the treasury, suddenly the panic stopped.”

Of course, this was not the end of the crisis, though the extreme bleeding had been stopped. The next few months were dedicated towards stabilising the banks and the country’s macroeconomic health.

On the banking front, part of the problem had been that the banks had been using depositor money to invest in the stock market, which had crashed dramatically over the course of 2008. The benchmark KSE 100 index had peaked on April 18, 2008 at a level 15,676 and then crashed until it hit 4,815 on January 26, 2009, a peak-to-trough decline of 69.3%.

On that front, State Bank Governor Salim Raza and his team came up with a plan: instead of forcing the banks to recognize their losses all at once, they would be asked to quantify the full scope of the loss and then recognize one quarter of it for every quarter over the course of the calendar year 2009. Not only did that divide up the losses, but it also allowed the banks more time to shore up their reserves, and it allowed the markets to recover, resulting in lower losses than were anticipated in January 2009.

With respect to the macroeconomic indicators, it was abundantly clear that Pakistan’s current account deficit needed fixing. “Because of the global financial crisis, we knew we could not rely on exports picking up and we knew we could not count on foreign investment,” said Tarin. “That left only one source of dollars flowing into Pakistan: remittances.”

“At the time, most of our remittances came through the hundi/hawala channels, and only about $5 billion came in through formal channels. We created a task force to study that and bring most of it into the formal banking channels. We created the Pakistan Remittance Initiative, which was tremendously successful and this past year, we crossed $20 billion in formal remittances.”

The PRI has widely been seen as a remarkably successful initiative and Pakistan consistently ranks among the World Bank’s studies as the cheapest country to send remittances to in terms of transaction costs.

Have we learnt anything?

The banking system in Pakistan today is considerably safer than it was in the swashbuckling days of the Musharraf Administration. Banks have far more restrictions on their ability to invest in stocks, and they are also much more limited in their ability to make riskier consumer loans, which means that there are few borrowers who are likely to be hurt by reckless lending practices on the part of the banks.

But in Pakistan, the problem never really started with the banks, and so solving the banking problem will not really stabilize the Pakistani economy. The problem was, and remains, the federal government, and on that front, just about nothing has changed, right down to the insane obsession with the exchange rate, the desire to artificially and recklessly shield urban upper middle-class consumers from higher energy prices, and a willingness to let the rich get away with tax evasion.

While the government led by the Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI) is attempting to deal with at least some of the wreckage left by its predecessors, it is far from clear if they have the ability to steer the government of Pakistan away from its current status as the single biggest threat to the country’s macroeconomic stability. In Pakistan, it was never the banks that were too big to fail, it was the government. And that remains truer today than ever before.

What an absolutely gripping article! But I do wonder if PTI has the wherewithal to get out of this one today. Not only do I lack confidence in their ability for action beyond words, I have a major concern about the geopolitical aspects of the IMF support that has been there for us throughout history. I do wish if someone can throw some light on the current situation.

Thanks for this article. It is very illuminating and explains very nicely how our forex situation led to problems with our domestic banking.

PTI is repeating some of the same mistakes as Musharraf. Petroleum product prices haven’t increased even though they make up 23% of our imports and their prices are rising in the international market. Instead they are increasing duties on cheese!

Comments are closed.