It was April 2018 when Sarah* called for a driver from a popular ride-hailing company to her office at about 9:30pm at night. When the driver showed up, she got in and told him the address to her home. A ride that usually took her half an hour, had already taken around 50 minutes and she still was nowhere near her home. Busy texting her friend, she noticed the time on her phone and asked the driver what was taking so long. The driver responded by saying there was a traffic jam and he had hence taken a longer route. Urging him to hurry up, she got busy on her phone again. As she felt the car coming to a stop, she looked up and outside the window. She was clearly in a different area. The driver had instead stopped in a deserted street. What happened next would remain etched in her memory forever.

The driver had turned around, and had a knife pointed at her. He ordered her to quietly get out of the car, and follow him to his friends’ apartment. Trembling with fear, she got out, and in a moment of madness, started screaming hysterically. Luckily, a few people from the neighboring house got out and saw her, which led the driver to flee.

While Profit has not been able to independently verify Sarah’s identity or story, it is by no means a unique or unusual one. Women narrate such experiences on social media quite often, which makes one wonder, is the ride-hailing business not safe for women In Pakistan? And have businesses tried to do more to ensure women’s safety?

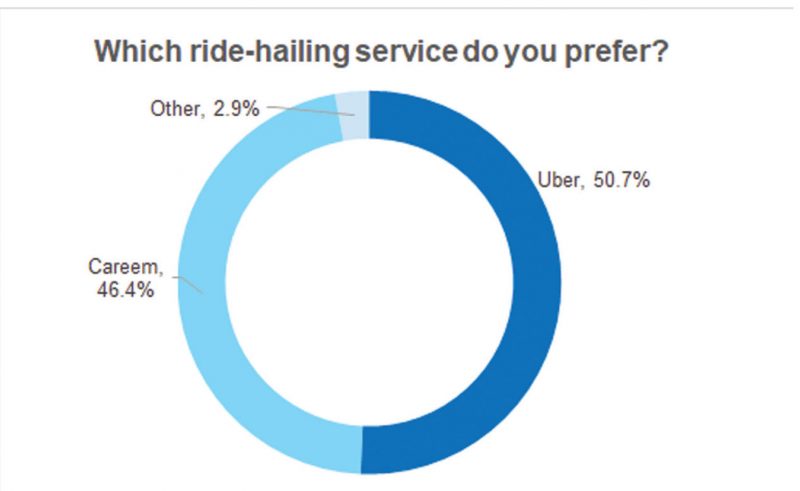

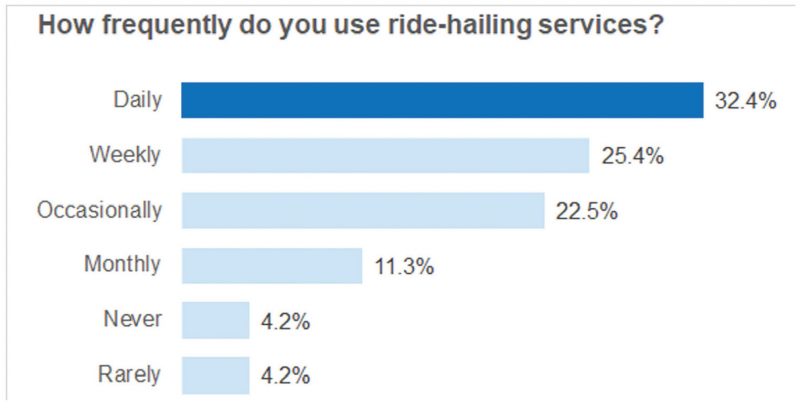

The birth of ride-hailing services such as Uber and Careem has had a massive impact in Pakistan. The ride-hailing concept has itself been a game-changer and has made travel easy, convenient, and personalized. But in this, as in many things, the ability of women to take advantage of this convenience is more limited than that of men.

In a survey conducted by Profit, 30% of women who have used ride-hailing services say they have felt unsafe in them, and 15% said they have faced harassment. And when asked about what might make them a more frequent user of the services, nearly 59% of women surveyed said that increased security, and 33% said the ability to select the gender of the driver.

For women, by women

A few companies are trying to change that situation and offer more security for women. In March 2017, a new company entered the ride-hailing business: Paxi. The company started operations in Karachi with three unique features; the option to call the ‘captain’ through an SMS or by calling its call centre, uniform-clad drivers, and a ‘Pink Taxi’ – a service for women, by women.

Zahid Sheikh, the CEO of the company, had then said the company wanted to provide women with an equal opportunity, and a safe environment for women passengers as well as captains.

Careem, in 2016, had also updated its fleet with female captains who would pick both male and female passengers. Paxi, in a bid to differentiate itself, and perhaps provide a more exclusive service, ensured its female captains would only operate for female passengers.

“The idea behind Paxi was a transport service, especially for women. We started Paxi in the hopes of capturing the female audience, and to provide a more convenient and safer environment for women in Pakistan”, says Iqra Hameed, Paxi’s former marketing manager.

In 2017, Paxi announced that it will ‘soon’ start its operations in Peshawar and Islamabad.

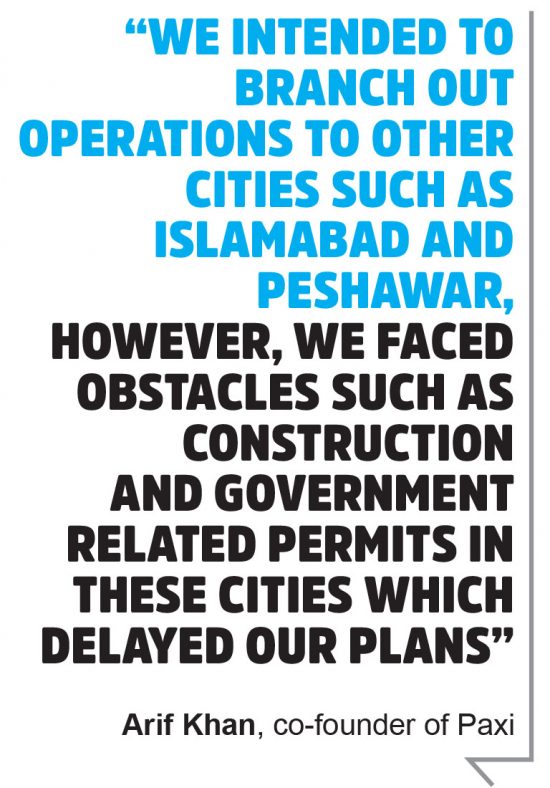

“We intended to branch out operations to other cities such as Islamabad and Peshawar, however, we faced obstacles such as construction and government-related permits in these cities which delayed our plans,” says Arif Khan, co-founder of Paxi.

With a population of more than 23 million people, Karachi is a city that has seen exponential growth and urbanization. It is a major hotspot for new businesses, eager to explore their options in the area and achieve rapid growth. It also still has the single largest concentration of middle class Pakistanis who have the kind of spending power that would form the target market for any such startup.

Since 2017, Paxi, a company which has seen steady growth and has received considerable coverage from the media, has only been able to increase its fleet of female captains to 12, confirms Arif Khan. “We have had to train our female captains on customer ethics, self-defense, CPR, and especially in panic-situations that frequently occur in the Karachi traffic”, he says.

At present, Paxi operates at the same pace it has been since the last year. Its co-founder estimates that it will take years to popularize the concept of a female-only ride-hailing service in Pakistan.

Equal opportunity for all

Another entrant called ‘Safr’, found the spotlight last year in Lahore when talks of a women-only ride-hailing service circled media outlets. Somewhat counterintuitively, the inspiration for Safr was not local to the Pakistani market, but came originally from the United States market. Michael Pelletz, an ex-Uber driver from Boston, realised the need of a female-only service similar to Uber, and created ‘Chariot’.

While the company called Chariot didn’t work out as planned, the idea struck a chord with Pakistani-American Zain Gillani, who acquired the company, re-branded it as ‘SafeHer’, which later became ‘Safr’. The new owner of Safr saw the need for a by women, for women ride-hailing service in Pakistan, and set out to create a team in the country.

“The concept of Safr is simple. It is a ride-sharing platform for women who have had to use public transport, and face the risk of assault, unwanted stares and advances from men”, says Syeda Ramla Hassan, CEO of Safr.

“Women face harassment on a daily basis. While cases are frequently reported and heard, I suspect that most are not even reported. Even if we look at the surveys conducted by UN Women, by the Government of Punjab, or by the Aurat Foundation, 90% of women who participated in the surveys in Lahore had faced sexual harassment in public transportation., and over 82% had faced harassment in bus stops”, adds Ramla.

Safr believes that the people of Pakistan want a new and reliable service for women who can safely travel from point A to point B, irrespective of the time and location. “Most of the people we have talked to have faced issues with male captains, and would welcome a female-only service”, says Ramla.

Among the women surveyed by Profit online, there seems to be at least some support for Ramla’s hypothesis, though perhaps not as strong as she might expect it to be. Of those surveyed, 41% of women stated that they would support a women-only service, while 59% stated that they have no gender preference.

Some of the detailed responses indicated the prevalence of stereotypes of female drivers, especially among men who use ride-hailing services, regardless of whether they support or oppose a female-only ride-hailing service. One respondent commented that he would rather choose a male captain since female captains are known to drive slow. Another user said that his niece was almost robbed and kidnapped on gunpoint and she had to get out of a moving vehicle. “I think a woman-only ride-hailing service can be very successful,” he added.

In a separate survey, Profit asked what they would choose if people were given the option to choose the gender of their captain. Out of the 358 responses, 240 (67%) said they would choose a ‘male’ captain, while 118 (33%) said they would choose a ‘female’ captain.

Most of the respondents (both female and male) suggested that the main difference between a male and a female driver is the experience of driving in crowded traffic.

Safr’s CEO further shared her disappointment with the ride-hailing services currently operating in the country, and about how they had failed to live up to their promises of equal opportunity, freedom of movement, and creating job opportunities.

“When I see stories posted by people and women on social media and hear of these incidents of harassment, it tells me that the promise made by the ride-sharing companies that we have, have not been fulfilled because women still face harassment in one way or another on a daily basis. So, when a woman driver is not comfortable picking up a male passenger at night, her work hours are automatically limited, and hence her earning potential and freedom of movement are also limited.

“This scenario is not just prevalent in Pakistan, it’s all over the world,” she adds.

Paxi, initially had intentions to become the primary go-to service for Karachiites. However, with the rise of Uber and Careem, it had to focus on its niche, and develop its female-only business. “With 12 female captains currently on board, it’s hard for business to flow on a regular basis”, says the company’s co-founder.

Arif Khan also told Profit that female captains hardly get regular passengers throughout the day, and hence, are paid a monthly salary.

“Our female captains are currently providing pick-and-drop services for women who have to go to and come back from offices, schools, and universities. We also pay them commission for any other passengers they pick throughout the day.” he explains.

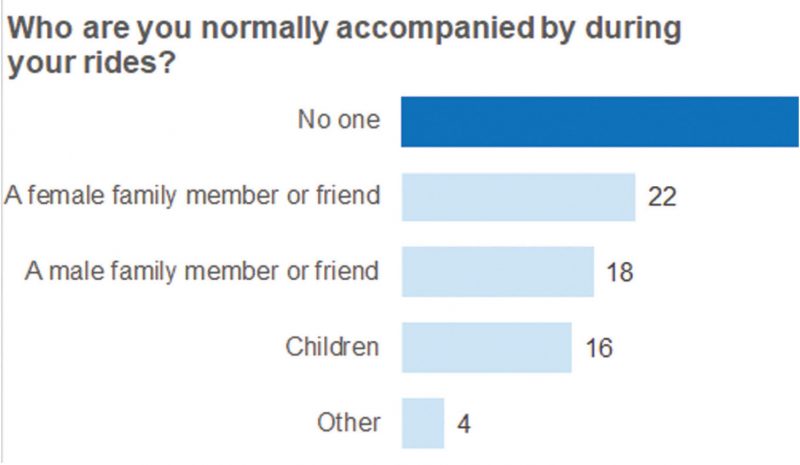

For women, working during the night is almost an impossibility due to family reasons, society, and culture. Fathers have issues allowing their daughters to travel late in the night, husbands seldom allow their wives to work at all, and single women find it difficult to work late and face harassment. As found out in the survey conducted by Profit, most women have trouble travelling in the evening, especially with male drivers.

Profit sought comment from Careem Pakistan about their female captains, but the company declined to comment.

Failure to launch

It is clear from both survey data as well as anecdotal evidence that there should be at least somewhat of a market for ride-hailing services that cater to women, particularly as a means of solving for the rampant harassment problem in the country. Both Paxi and Safr have attempted to create that solution, though both have had difficulty making headway into the market against their larger competitors – Careem and Uber – for different reasons: Paxi has a problem scaling its operations, and Safr has trapped itself in a cycle of planning and public relations without actually launching operations.

In the case of both companies, at least part of the problem in scaling appears to be a lack of funding. Both Uber and Careem have poured millions of dollars into seeking to capture the approximately $300 million (and rapidly growing) ride-hailing market in Pakistan. Those are the kind of resources not available to the founders of both Paxi and Safr, though it is not entirely clearly if they have sought such funding and been unsuccessful, or whether they have not even tried to obtain growth capital from external investors.

Pakistan’s venture capital industry is small, but has been attracting growing interest from institutional investors looking to capitalize on the opportunity for promising tech startups in the country. For their part, while the management team of Safr appears to have identified a market niche they wish to serve, they appear to believe that their biggest challenge in creating a business that can scale has more to do with societal factors than their own lack of financing and marketing.

“The problem is that the society has restricted its female population and its freedom of movement by enforcing a draconian culture that does not allow women to go out, or work late at night,” says Safr’s CEO.

As for the company’s marketing efforts, the company appears to be relying on low-cost methods to try to get the word out: “We’re in talks with some major banks, NGO’s, and other financial institutions to help us get more awareness for our app. We’re also in talks with some people in the red-light areas so we can onboard females who have not had the privilege to receive proper education and hence get employment,” says Ramla. “The idea is to get make people more aware of the concept of a female-only ride-hailing service first, and this is why we are focusing on promoting ourselves. We hope to launch our services soon.”

* Names have been changed to protect people’s identities.

i think major question is not whether people have preference for women only service. question is those who are interested, are they willing ot pay the premium for that? if people are willing to pay a premium, ride hailing services can introduce a feature of woman safe drivers, those who are regestered with local police and have their background checked. This will make them have a certain premium over others.

Uber is losing its credibility in the race of making money. Uber increase its charges as well as hidden charges on the name of fixed fares. 2 months ago I used to give 200 for my fare now when once a blue moon I got 50% discount I pay 200.

Some times same per km/minute rates exceeds.

I avoid using uber now. Most of my family n friend to whom I referred uber are avoiding uber.

Mohammed Aslam Mohammad Sadiq age 27

Comments are closed.