Ask the scholars that spend decades obsessing over Japanese aesthetics and they will tell you tales of loft ideals and an ideology of beauty. They will wax and wane philosophical about the transient and stark beauty of wabi, the beauty of natural ageing known as sabi, the profound grace in the subtlety of yugen.

The modern study of Japan, in particular Japanese aesthetics is perhaps the most understated yet currently most prevalent oriental enterprise in existence. Perhaps it is based in history, the fact that Japan remains uncolonised – the undiscovered pearl of the East that the great European empires failed to make their own. Whatever it is, there is a defined fascination with all things Japanese.

But where the scholars would prefer to be known as academics engaged in Japan studies, the overarching phenomena comes down to one word: Weebs. A weeb is a derisive term for a non-Japanese person who is so obsessed with Japanese culture that they wish they were actually Japanese.

More than anything else, a weeb is a category of people. It is greatly an American export, once again going back to history, perhaps because of the states’ latent guilt over their atomic adventures in Japan at the end of the second world war.

Weeaboos are usually characterised as a laughable counterculture. In a country like Pakistan, however, to be a weeb you need a certain level of exposure not just to Japanese cartoons, products and traditions, but also some understanding of the American subculture.

Why this small section of society is important to us is because they make up a market. A market that has a somewhat inelastic demand, because the product is something the consumers are passionate about and because they have the money to spare.

In Pakistan, MiniSo is the brand cashing in on the Japanese aesthetic. Walk into one of their stores, and you will feel like you have just been shoved by the Tokyo crowds into a Japanese outlet store. Their stores are sleek, all white walls with tinges and borders of red, set out like a sci-fi movie. They do not pander aggressively to the weeb crowd (you will find no anime posters or katana replicas), but it does have a very modern Japanese vibe. From the soap dish alarm clocks to their knock off earphones, keyboards, bottles, lego sets, towels, slippers, cutlery, speakers, stationary and all number of other products – everything is decidedly Japanese.

Everything, that is, except MiniSo itself. For despite its Japanese name, design and branding, MiniSo is a Chinese mass retail brand, and they have successfully made inroads all over the international retail segment, and Pakistan is no different.

MiniSo entered the Pakistani market in 2017, but started its earlier operations in China in 2013. Thus far, MiniSo has operations in 60 countries and regions including the United States, Canada, Russia, Singapore, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Korea, Malaysia, Hong Kong (China) and Macau (China), with an average monthly growth rate of 80 -100 stores. According to the website of the company, MiniSo has opened over 3,500 stores worldwide in five years of operations, with business turnover reaching US $2.5 billion in 2018.

In Pakistan, MiniSo opened its first store in 2017 and reached to 45 stores in just 2 years. And things are only getting started.

The Japense aesthetic

MiniSo is not the only entrant in the international retail segment and in Pakistan. Two more brands with similar concept have also jumped in to lay their claim on the pie, but are rather very small as compared to MiniSo. These other two brands are XimiVogue and Latt Liv.

The story, however, is the same. Both of these brands also sell themselves as Japanese retailers, but they are headquartered in, you guessed it, China. They were started in, began their operations in and continue to have their major operations in China. They make their products in China, all or at least one of the cofounders are Chinese, and yet, all three of them insist that they are not Chinese.

In the retail business, especially designer retail as brands like MiniSo are, image is everything. And if you are a Chinese retailer, it is not going to be a same-noodle-different-sauce scenario. If you tell your customers you are a Chinese retailer that makes its products in China, they will immediately think cheap and perishable. If you sell it to them as Japanese, they will immediately think high end, high quality. This leads these retailers to adopt identities to best market themselves.

For instance, MiniSo portrays itself as a ‘Japan-based designer brand’, though the bulk of its operations are in China and their initial operations actually started in the Chinese market in 2013. In China, it operates over a thousand outlets opened in a span of a few years. The company was originally founded in Japan in September 2013 by Japanase designer Miyake Jyunya and his Chinese partner and president of the company, Ye Guo Fu. In the month following the opening of their office in Japan, the founders moved on to China and set up an office in Guangzhou, which became the headquarters of the company. The initial Japanese branch, and designer, thus become simple tools to give legitimacy to their farcical illusion.

MiniSo has been criticised for masquerading as a Japanese brand even though it operates only a handful of stores in Japan while its stores in China are over 1,000. In an interview with Singaporean publication The Straits Times, MiniSo founders had to defend the company’s Japanese origin and insisted that it is actually a Japanese designer brand, even though media reports say that when MiniSo launched in China, it had no outlet in Japan. The founders even had to defend the name which sounded like Japanese retailer giant Daiso, and its logo which resembled that of Uniqlo – another Japanese retail brand.

Similarly, XimiVogue, also known as XimiSo, calls itself a ‘Korea-based designer brand’, while Latt Liv categorises itself as a Scandinavian concept brand.

The Chinese context is important. Given the reputation of Chinese retail products particularly in the lifestyle category, it’s not surprising that these brands would run away from their true origins and try to portray themselves as something which they are not. There is a lot of stigma around Chinese products which are shunned, at least by Pakistani consumers, for being low on quality. And as such, the stigma around Chinese products would kill the market even for the best of these products.

But an insider tells Profit that these brands are actually Chinese and their products are ‘made’ in China. Giving it a spin to make it look like a Japanese brand is a marketing strategy, or rather a gimmick of sorts, as Japanese products are well respected for their quality and well demanded in the international markets including Pakistan.

For these brands, courtesy the inexpensive product manufacturing value chain in China, it is the convenient prices that make the model attractive. Aesthetically pleasing, good quality lifestyle products ranging from kitchenware to health and fitness to fashion can be bought from any of these brands at a low price. Imagine the customers you would pull if you had (supposedly) Japanese products to sell, for as low as Rs200-250 per item.

The business model

MiniSo’s business model is an innovation of the traditional retail business models that we are familiar with. Its strength are the low price products because of low-cost retailing model, but one that has been tweaked to keep customers coming back.

MiniSo keeps costs and consequently prices low because its products are designed in-house and it has an efficient supply chain. More importantly, however, low prices are a result of low margins that the company earns for itself. Forbes reported citing MiniSo founder Ye Guofu’s interview with Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business in the spring of 2017, that the company’s gross margin was a tiny 8%.

So how does MiniSo keep customers coming back for its products?

At each MiniSo store, only a limited range of products is offered with a limited stock. This yields in a high inventory turnover. So if you like some products at MiniSo, which you surely will because the products are really nice in design and quality, you better rush to the store and buy it as quickly as possible because the stock is more limited, and if the stock depletes, the same range would not be available. It would be replaced with a new range though, with even better looking, high quality products, creating a treasure-hunt sort of an experience for the customers, who keep on coming back, fascinated by some of the best looking products at very low prices.

Making millions?

MiniSo, like most things Chinese in this century, likes to be in control. All over the world, they run their vast array of shops themselves, preferring to micromanage everything. In Pakistan, however, the majority of the MiniSo stores you see are franchises.

In an interview with Aurora magazine in December 2018, MiniSo’s General Manager for Pakistan, Kezhi Jiang, had said that a majority of the stores worldwide were company operated but for further and a rather rapid expansion, MiniSo was putting stock in developing and implementing their franchising model.

If you were to get a MiniSo franchise in Pakistan, it would cost you a non-refundable management fee of $3,500, charged one time for 3 years, which comes to a total of $10,500. In addition to this, there is a non-refundable franchise fee of $15,000 charged one time – both these are exclusive of taxes; another $15,000 as security deposit charged as a refundable amount.

MiniSo also charges $200 per metre square as advance renovation fee, $380 per metre square as advance furniture and fixture fee, $500 per metre square as advance first batch of goods fee and $8,000 for first batch of replenishment goods. All in all, the franchise cost, including the cost of the inventory for the first shipment, furniture and renovation, all of which depend on the size of the shop, the total for getting a MiniSo franchise for any location in Pakistan will cost you anywhere between $210,500-$372,500. That is obviously plus tax and that does not include rent for the outlet, which is to be borne by the franchisee.

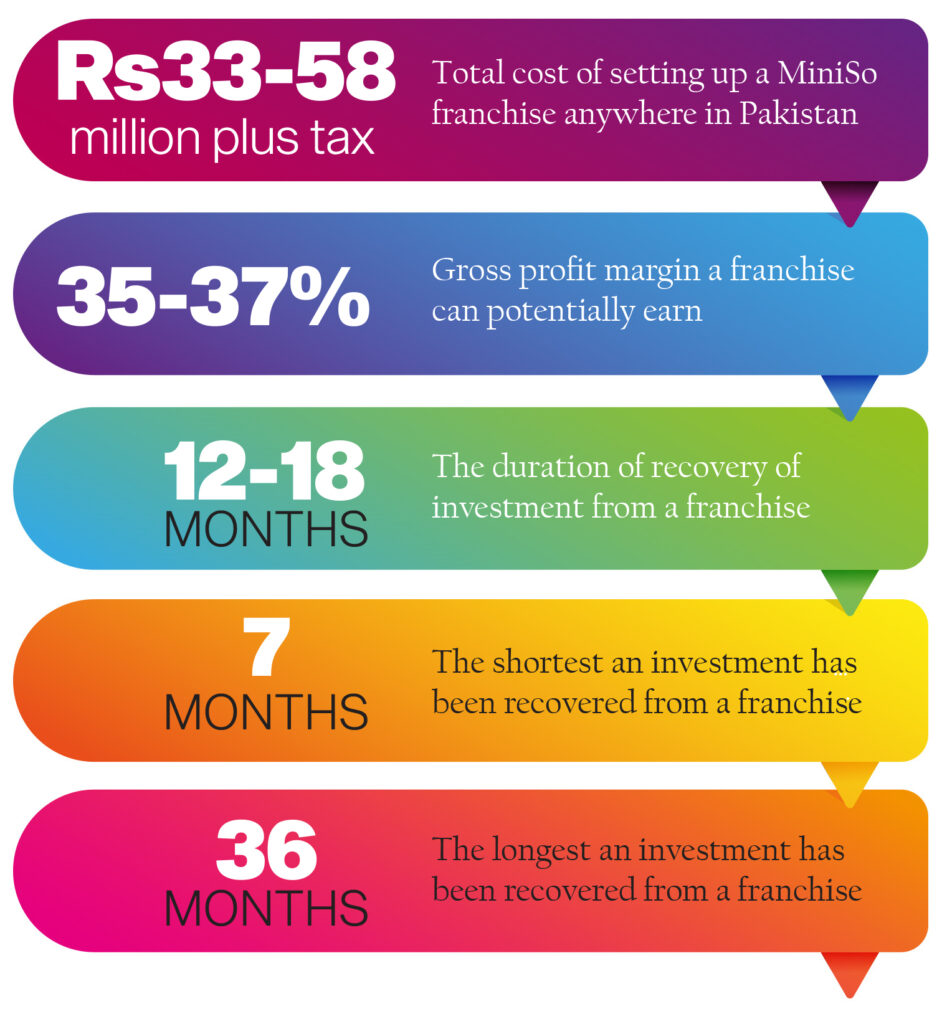

That would be Rs33,048,500 to Rs58,482,500, at Rs157 for the dollar, plus taxes and rentals, for anyone who can foot the bill. The return on investment is something MiniSo claims has the requisite bang for the many many bucks a franchise owner will have spent. They claim to promise a gross profit margin of 35%-37% to all franchisees, while the return on investment is between 12-18 months.

For those with surplus money and looking to invest, MiniSo can be a gravy train. An industry expert told Profit that the margin offered by MiniSo to its franchisees is very lucrative and the shortest an investment has been recovered through a MiniSo franchise is seven months, while the longest it took to recover an investment has been three years.

Of course, MiniSo is not invulnerable to the calculus of foot fall and how certain locations bring more footfall to the store than others, MiniSo is cautious about where its outlets are opened. The company has currently identified more than 100 locations where they want to open outlets. And while contracting a franchise, the location of the store is mutually decided by the company and the prospective franchisee.

An industry expert Profit talked to said that for a business like MiniSo, market of every location where a store is to be opened will be assessed, with the markets where the commercial activity is high is where an outlet should be opened.

Though both parties can propose markets, the franchisee shares multiple store options out of which Miniso finalises according to their criteria. And, as Profit got to know, MiniSo has rejected some franchises because of low commercial viability of the locations.

Franchises facilitate the company’s philosophy of rapid expansion. Multiple franchises would mean investment being mobilised quickly to open stores simultaneously. And many franchisees have contracted more franchises after opening their first outlet, which is a testament to the profitability of the business. Another testament to the success of such outlets is that no franchise owner has shut down a shop or even relocated to a different place due to a lack of sales.

An industry expert told Profit that MiniSo’s marketing for the franchises is done primarily through store artwork and word of mouth as they want consumers who are already familiar with their brand to partner up with them. Social Media platforms are used occasionally as well and more recently, MiniSo advertised discounts on social media for franchises to attract people to invest in MiniSo franchises despite a slowdown in the economy.

Giving its franchise model competition is XimiVogue. XimiVogue, also headquartered in China in the city of Guangzhou, has over 1,500 stores in 80 countries worldwide which it created in a span of 10 years, earning a total revenue of more than 2 billion RMB in 2018 (approximately US$297,876,140).

XimiVogue’s Pakistani presence is small with only 14 stores operational in major cities. It plans to increase this number to 25 in a year’s time.

Now here’s what a XimiVogue franchise will cost you: for a three-year contract, a franchise fee of US $15,000, a management fee of $10,000, refundable security deposit of $10,000, basic store renovation at $200 per metre square and $600 per metre square for the initial stock of goods. All in all, for a 93 square metre store, XimiVogue would charge you a total of $132,560, that includes $76,850 for the complete store and $55,800 for the initial stock, exclusive of applicable taxes.

In rupee terms, at Rs157 for the dollar, it comes out to Rs16,835,120 or Rs16.83 million, plus tax. That is cheaper than a MiniSo franchise but the costs do not end there. A franchisee would also have to bear the costs for the shop rent, staff costs, utilities, taxes, registration and license fees etc.

Moreover, there are certain shopping malls in Pakistan with specific standard requirements and if a franchisee selects such a location, the cost of complete store renovation will increase by the additional costs incurred.

And for the cost that is apparently less than a MiniSo franchise, XimiVogue offers a higher margin of 45%-49% – 10-12% higher than what MiniSo offers.

However, Profit’s observations and conversations with the staff at the malls in Lahore where both these brands are present, revealed that though both the brands are considered hip and hot by customers, it was MiniSo that had a greater foot fall at its store in these malls as compared to XimiVogue. Even the staff at one of the outlets of XimiVogue admitted that where there is MiniSo, XimiVogue gets a beating. On the other hand, Latt Liv is too small and has only a handful of company-operated stores in Pakistan. And its franchising model is yet to start.

you can earn 13-14% at zero risk by buying govt. bonds. you can make hundreds of percent by buying bitcoin. 35-37% return is not enough considering the immense risk and hassle related to running a business. in addition to the costs mentioned here there is also extortion money that has to be paid to various entities that come after IRL businesses.

is that 13-14% is monthly return? i am a little confused please clear that THANKS

annual

returns are always given as annual rates.

the title of this article reminds me of that old joke about how to become a millionaire – start off with 10 million!

13% annual returns on PKR is nothing to write home about.

Currency depreciation is almost 10% YoY which translates to net 3% ROI YoY on gov. bonds.

How to earn by govt bonds?

I have always wanted to invest for passive income. Would you be kind to advice me.

An informative article. Thanks for the effort.

yes but now miniso started online selling platform as well which is minisoonline.com.pk

Comments are closed.