The locusts are finally catching up with us. How this has happened has been a sordid tale, one well recorded by the cover story of Profit’s previous issue. But in essence, it has been a long tale of neglect and the federal government turning its head and hoping the problem will go away.

As per reports, the first swarm of locusts had come from the United Arab Emirates in mid-2019, and in the next few weeks time another new infestation arrived from Iran. There were early warnings that the problem could get out of hand. As early as May 2019, Muhammad Akram Dashti, a senator from Balochistan, was giving speeches in parliament urging the federal government to start preparing for the locust plague that had just emerged in his province.

It took the government the rest of the year until they finally declared a state of national emergency in early 2020. Originally, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) had said the locust invasion was initially expected to subside by mid-November. The government decided to wait for this and let things smooth over, instead of actively trying to remove locust eggs and nests. This, along with weather conditions favourable for locust reproduction, has the FAO now saying that the second generation is 20 times bigger. Locusts move in swarms of up to 50 million, can travel 90 miles a day, and lay as many as 1,000 eggs per square metre of land.

“It could have been prevented,” Senator Dashti now says. “I raised this issue when it was confined to a division of the Balochistan province. It was the responsibility of the federal government to help farmers against such destruction, but the federal government didn’t take it seriously. I requested for spraying of crops time and again. Nothing happened.” Now, he says, it is too late, and many people will starve.

The senator is correct. There are now legitimate fears of food shortages sweeping through government circles, and farmers across the country continue to suffer. According to the FAO, Pakistan will incur losses of about PKR 353 billion in winter crops, such as wheat and potatoes, and a further PKR 464 billion in the summer crops being planted now. An update from the FAO last month warned that “it would be imperative to contain and control the desert locust infestation in the midst of the additional impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on health, livelihoods, food security and nutrition for Pakistan’s most poor and vulnerable communities”.

The Guardian reported looming catastrophe as well, saying it will be economically devastating for a country where agriculture accounts for 20% of GDP and 65% of the population live and work in agricultural areas. “Pakistan is already suffering from crippling inflation, which is now at a 12-year high, and the unprecedented economic burden imposed by the coronavirus pandemic,” the UK publication wrote. The cost of flour and vegetables had already risen by approximately 15% since the beginning of 2020, and the locust infestation, if not tackled timely and in a cost effective manner can lead to even basic food staples becoming unaffordable for the masses.

State minister of Agriculture for the worst hit province, Sindh, Ismail Rahoo called the plague a “dangerous and catastrophic threat to the economy, agriculture and food security in Pakistan”. Speaking to a media outlet he said last month that the swarms would “be ten times worse than last year. They are attacking from three sides. The locusts and their eggs have now covered 50,000 square kilometres of farmland. We are expecting them to infest more than 5m hectares. And they are not just attacking Sindh province, but also the agricultural areas of Punjab and Balochistan.”

The questions you should be asking

One positive is that the locusts have not gone unnoticed, garnering local and international media attention, with little remaining that has not already been covered by the mainstream media when it comes to locusts attack, potential wheat shortage and the price inclinations. But this kind of attention in the middle of a pandemic also shows the depth and seriousness of the problem.

However, a shortage of food and a corresponding increase in both the imports and price of wheat and other food grains is not inevitable. And what is not being discussed is the impact that these higher imports will have on the economy in the long-run. It is not likely to be a one-time crisis where food fell short and the federal government jumped in with some extra borrowings and saved the day. Such a crisis, irrespective of what its short-term solution is, leads to several deeper and long-term problems for an economy, especially an economy like Pakistan.

There is a network of industries and an entire cycle of production at play here. When the wheat crops will be reduced, that would not only directly impact the farmers and landowners, but it will also have a trickle down impact on the threshers, the flour mills, the transportation sector for wheat, as well as the marketplace for byproducts of wheat. In one glance, it is clear as day that the government might be able to make up for the end product quantity required for consumption in the country, but what about the entire chain of production and transportation that will suffer as a result of the lower wheat crop? What about the entire process mismanagement, and not to mention the vested interests for profiteering?

There have also been reports of Pakistan exporting close to 0.7 million tonnes of wheat towards the end of last year despite the raging fears of wheat shortage brewing since as early as 2019. Some corners of the government have been heard saying that only 40,000 tonnes were exported to Afghanistan and that was also to be a mode of diplomacy more than a trade factor. Here, it might be notable to recall that despite exporting north of a million tonnes back in 2018, Pakistan faced no shortage in home markets. Products like these are traded as a result of the stabilization policies for food crops, and not the other way round. Making a preemptive decision to export wheat, irrespective of whether it was done with or without the government’s knowledge of the impacts it would have, is undeniably a corrupt move, and one that will have long term and devastating impacts on the country’s economy.

What happens now that we are in the eye of the storm?

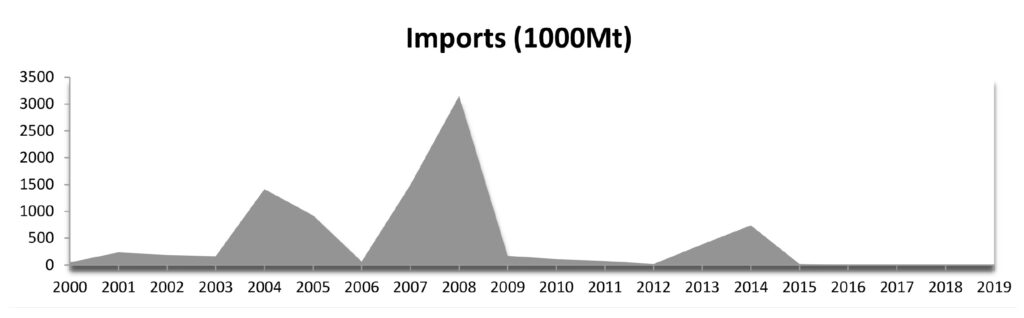

One of the ways to see the potential impacts of the current wheat crisis and resulting requirements of imports will be to see the economic impact of a similar move that happened in 2007-8. The crisis might have taken a different form back then, but the turn of events was the same. The international price of wheat exceeded the local price and wheat was exported before, and more than it should have been in the first place.

In 2007-8, when wheat stock was in surplus within Pakistan, the federal government under Musharraf administration Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz, exported around 4.3 million tonnes of wheat. The prices kept moving up and our local profiteers, possibly under the argument of earning foreign exchange for the country, kept exporting wheat until it started to present a shortage in the local market, which meant wheat had to be imported at a much higher price from the rate at which it was exported.

In the later half of 2008, the Pakistan People’s Party’s Gillani administration increased the wheat support price by around 50 percent which corresponded to the international price falling down and remaining below local prices up until last year, except for a small bump in 2011.

Higher local wheat price led to food inflation across the food basket and also had a trickle down impact on inflation otherwise. It was not just the entire chain of production that saw an increase in their income as well as their prices, but the related products of wheat, such as a feedstock as well, which in turn increased prices for milk and meat.

Now, the government has once again allowed unlimited import of wheat signing on the official import of 0.3 million tonnes of crops in May 2020, which is expected to rise a little further, and that too just for the first part of the year. The net impact of locust attacks and the rainy weather is yet to be seen for the rest of 2020. Considering the past data and the current situation in local and global markets, it is clearly a risky move as prices are heading upwards. Import price in 2020 would be higher than the prices at which we exported wheat earlier.

What is to be done?

For now, we seem to be repeating the 2007-8 actions, at least on a smaller scale, in 2020. To come up with the solutions, one should quickly revisit the causes of the problem. We did not have an accurate estimate of the extent of crop damage until April-May last year, and even then the government estimates did seem to show sufficiency despite the first locust attack.

This can be seen in notices issued by the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) in July 2019. There is also the factor of speculation when profiteering is factored in. in April 2019, when the news of crop damage began to make headlines, it caught speculators’ interest sooner than it did the interest of the government. The result has been higher flour prices instead of corresponding corrective policies and a corrective ban on exports.

The solution to the above problem can be directly traced back to the competency and the willingness of the government to take account of the situation at hand well before investors do, and to ensure that “diplomatic attempts” or outright brazen profiteering is not being done at the risk of local food shortage later. The government was warned time and again, but simply decided to bury their heads in the sand and hope the trouble would go away. There is not much to be recommended except perhaps that the representatives and governors of wheat policy are chosen based on merit and not on who pleases the one at the helm of affairs of the government of Pakistan.

Secondly, one might consider the possibly lengthier but more suited model for imports of wheat for Pakistan, now that we are directly looking at a wheat crisis. With the option of commercial wheat imports on the table, the likelihood of cheaper wheat making its way towards Pakistan is now higher. Instead of investing on a government scale, and yet again allowing unprepared and corrupt elements opportunities to try to resolve the issue only on the end-level of making sufficient wheat available for consumption, our government will be better off by allowing those operating within the supply chain of farming and harvesting crops to bring in the required quantities from the foreign market.

If this theory is correct, and the stakeholders directly related to the wheat crops start to bring in cheaper imported wheat, that would not only lead to stable prices, but will also preserve the chain of production, and thereby avoid the economic impacts created by the downfall of the related sectors of wheat production. The only negative impact will be for the seasonal profiteers, and some may say that is another added benefit more than anything else.

Finally, a somewhat more permanent and blanket solution to prevent premature export of wheat is to just get rid of the price-fixing policy. By pegging our local wheat price to international prices, we can at least ensure no involvement from these profiteers with the sole purpose of making some quick bucks.