Every day at 8am, Islam Sahab rolls up the shutters to the store ‘Chinar’, named after the tree species found in Kashmir. He sits there, in shifts, till around 12:05am (pre-pandemic), and 7pm (during pandemic). He has been doing this for the last 16 years, and in the process Chinar has become a fixture of Saba Commercial, a market located in the upscale DHA neighbourhood of Karachi.

Chinar is what you would call a mid-size store. Every day, there is a stream of customers from the adjoining residential areas. It is significantly larger than your average kiryana store, with two aisles, and it stocks limited foreign products. But it also retains aspects of the mohalla store; one can, for instance, have a running tab at Chinar, to be paid back at an almost undecided date. Islam Sahab recognizes and greets returning customers, some of whom have been shopping at Chinar for years.

Chinar exists in a particularly interesting location for retail options. Down the alley, is a paan store whose entire business model is predicated on staying open two hours later than Chinar, to serve the people who flock to the nearby dhaba. One kilometer away is Mustafa Store, which is somewhat bigger, cleaner and has three ailes. And in a two kilometer radius, exist the big three department stores, all taking up prime real estate along the seafront: Carrefour, Imtiaz, and Chase Up.

Islam Sahab is acutely aware of the differences between his store and the big three. Every day, he has to keep a check on the various distributors, from which he buys his products. The larger department stores can buy in bulk, directly from the consumer goods manufacturers. Meanwhile, Islam Sahab has to negotiate prices with distributors and build personal relationships.

Distributors who sell items that are frequently in demand are paid directly in cash; but sometimes he must also write eight-day cheques or 15-day cheques to distributors, with the expectation that customers will buy the products from the stores eventually.

This complex supply chain system – which distributor, which wholesaler, and what prices – is a headache for retailers like him. And there are around 700,000 traditional retailers in the country. What if someone made these retailers’ lives easier?

Around January 2020, two ambitious young ‘waapistanis’, Saad Jangda and Hamza Jawaid, were beginning to have this same conversation with each other. They decided to meet up with Mr. Waapistani himself, Aatif Awan, the founder of venture capital firm Indus Valley Capital. Ironically, or perhaps fittingly, the three met to bounce off ideas at Xanders, an upscale restaurant located in the very heart of that same two kilometre radius of Karachi that encompasses examples of all of the retail players that might be affected.

The end result? On June 1, 2020, Jawaid and Jangda announced that they had raised $1.3 million dollars for their new startup, Bazaar. It definitely raised eyebrows: that is Pakistan’s largest pre-seed round amount.

And they are not alone. A few days later, the startup Tajir – founded by brothers Ismail and Babar Khan in 2018 – announced raising $1.8 million in their latest financing round led by Fatima Gobi Ventures. Tajir competes in the same space as Bazaar, though it has the advantage of having been part of the 2020 incubator class of YCombinator, arguably the world’s most famous incubator, which produced the likes of companies like Airbnb, Stripe, Instacart, Doordash, etc.

And then of course, there is Jugnu, an app developed in August 2019 by retail technology company Salesflo. To Salesflo’s credit, it has bootstrapped Jugnu to over 10,000 retailers that it claims it has on its B2B platform. The founders of Salesflo did not disclose if they had raised any funds from outside, Crunchbase data shows that the company raised $500,000 on June 1, 2020 in a pre-seed round.

Salesflo is little different, in that it focuses on automation of the supply chain, but we will get to that in a bit.

These players have differing models, but all can agree on one thing: the current retail supply chain, as it exists, is inefficient.

The model

To understand Pakistan’s retail supply chain, all you need to be familiar with are four terms: manufacturer, distributor, wholesaler, retailer.

At the top of this food chain are the manufacturers; think Unilever or Nestle. They sell to two groups: large retailers, and distributors.

Large retailers are basically the aforementioned department stores, like Carrefour and Imtiaz. They can afford to have direct relationships with FMCGs because of their scale and their size, and can buy products in bulk.

Which is great, except these stores are not really indicative of Pakistan’s retail sector. As Babar Khan, in his blog on Tajir points out, 91% of retail flows through independent ‘mom-and-pop’ stores.

This is where the distributor comes in. Around 40 years ago, manufacturers in Pakistan would go to the trouble of setting up distribution channels themselves. Today, these distribution channels are separate, but no less formidable. Distributors will have their own fleet of vans, their own delivery staff, and manage their own inventory coming in from the manufacturer. The distributor goes on to sell to two groups: retailers, and small wholesalers.

The first group is pretty straightforward: these are store owners. The second group is basically a marketplace for very small retailers, or kiryana stores. This is a store that is not served by a distributor, for no real reason apart from it having very low volumes.

It is possible as a retailer to have all three places to choose from. It could have a direct relationship with a manufacturer for some products (usually unlikely), and it could also maintain a vast network of distributors for some goods. It can also buy from the small wholesaler. Many kiryana stores also buy not just from small wholesalers, but from the large retailers themselves. This is how one often sees quasi-distributors, shopping in bulk at places like Carrefour, alongside other customers.

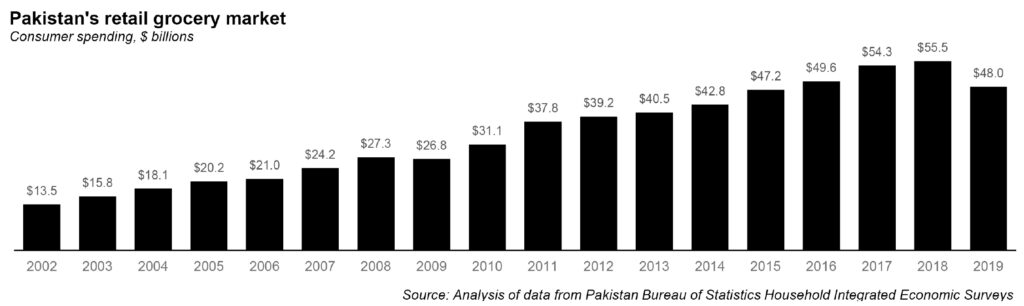

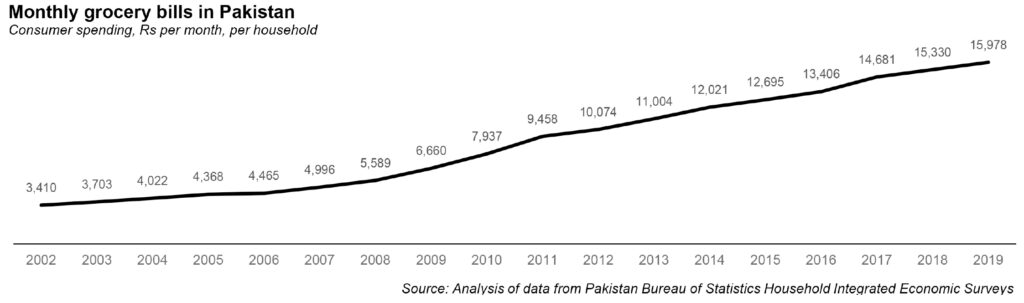

This is an inefficient system for a retail industry worth $125 billion a year, of which $48 billion are just groceries, according to Profit’s analysis of data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics’ Household Integrated Economic Surveys.

Also, the distributor is not just selling to the retailer. The retailer actually has to wait around for designated sales people to arrive to take orders, or an order booker. This is why so many kiryana stores have to go to small wholesalers to begin with; distributors simply do not have enough order bookers around, and so focus on the larger retailers.

Pakistan has approximately 650,000 to 700,000 kiryana stores. No consumer goods company is able to distribute products to all of them. So they work through the distributors, sub-distributors and wholesalers to get the products across to those retailers. However, smaller manufacturers generally have difficulty in sustaining supply chains in rural areas as their cost to serve each retailer is high: each order booker, engaged to make a run at one shop incurs costs and time for orders that tends to be small, with thin margins to begin with. It simply does not make sense to carry out these transactions.

And if you are a retailer, how do you know the price you are receiving is a fair one? There is no efficient way of comparing different suppliers’ price points. Again, it is the small kiryana store which oftens suffers, as it is the last player in the chain, and therefore the one with the least amount of wiggle room. If you pick up a product from a kiryana store, it is likely to have passed through a couple of hands – that is, if it arrives at all. Inefficiencies means that sometimes retailers have their orders delayed or cancelled.

And finally, a major point: someone has to physically go from the kiryana to the wholesale market to pick up goods. That person is often the store owner themselves, which means the store is shut for the time that they are gone, leading to a loss in revenue.

The wholesale market also reeks of counterfeit products. Being a small retailer is generally not a happy business to be in.

The disruptors

What Tajir and Bazaar decided to do is focus on eliminating those inefficiencies. They did so by creating online marketplaces accessible through mobile apps to enable retailers to buy a variety of products from distributors and be able to compare prices in a transparent manner.

Both companies sell it like it is a win-win situation for both parties. For instance, Tajir says that suppliers can enjoy greater sales at higher margins with zero additional investment. But to be clear, both apps are designed to empower the overburdened and overworked stressed retailer.

They also minimise how much influence a distributor can exert, or more accurately how annoying a distributor can be for a retailer. So, in the theoretical scheme of things, B2B players entering the market have great benefits in terms of taking out the middlemen in the value chain. That is what B2B solves and eliminates which has a clear value for the shopkeeper.

It could give shopkeepers direct access, helping them save precious time, clearing any ambiguity regarding the authenticity of the products they are selling. For the manufacturer, the benefit of optimisation: theoretically, bringing down cost to serve seems quite promising.

Tajir and Bazaar’s solution to end the problem is almost identical. One operates in Pakistan’s largest city, the other operates in Pakistan’s second largest city. Ismail and Babar Khan are brothers, Jangda and Jawaid might as well be brothers. The two went to middle school together at Foundation Public School in Karachi, often carpooling together. Both went abroad for their higher education, with Jawaid studying at London School of Economics and Jangda at the University of Michigan. Jawaid decided to work at McKinsey in Dubai for four years after graduation; Jangda worked in advertising at Snapchat in New York, before becoming a product manager at Careem in Dubai, becoming Jawaid’s roommate in the process.

Jangda quit and moved home to Karachi in November 2019, with Jawaid’s work frequently flying him home as well.

Both thought it was around the right time. “For any ecosystem you need three different things: You need the right talent, the right amount of funding, and a conducive environment to play in. The last one has been missing in Pakistan, and [that] has changed in the last two to three years,” said Jawaid.

For Jawaid, the impetus for a startup like this has always been to create value for the retailer. As he explains: “He, or she, is a stellar entrepreneur, running their store, running their finances, buying from their guys, serving their communities. He’s an e-commerce player who attends the shaadis and funerals of their communities. Yeh jo mohallay ki dukaan hoti hain, they are a key part of the community. They do a huge amount of business.”

After fleshing out ideas in January, the two talked to around 200 retailers in the city, asking them how they spent their day and how the supply side of the markets work. From there, the two ran a pilot program in mid-April, to test the waters. This was in the middle of the Covid-19 pandemic in Pakistan, which if anything, according to Jawaid, created a greater need for Bazaar, as stores’ timings were even further restricted. They then pitched to Aatif Awan, and San Francisco-based venture capital fund Alter Global, and commenced formal discussion.

Profit mentioned the earlier career achievements of Jangda and Jawaid to drive home a point: as according to sources, Alter Global specialises in looking out for talent from emerging markets that a) have gone to schools in the developed world, and b) have worked at foreign companies, and therefore have picked up those skill sets. Both Jangda and Jawaid fit the bill.

It is a view confirmed by Jesse Sullivan, the founder and CEO of Alter. He told Profit over email: “The team is exceptional in both its high character and its competency. The founders bring a mix of product design and operations experience from some of the world’s best companies, with their colleagues at Careem and McKinsey exclaiming to us their belief that these guys are future founders of a tech unicorn company. At Alter, we back role-model founders that are on a mission not only to build their company but also to build their country, and Saad and Hamza are on a larger mission to transform their country for the better through entrepreneurship.”

He added the VC has been interested in the Pakistani market for two years, citing the huge population, the rapidly growing smartphone/data use, and the gap in consumer and enterprise needs.

“There are so many inefficiencies in the market right now when it comes to small business owners. These shop owners have smartphones in their hands, and by bringing easy-to-use technology to their fingertips, Bazaar will make their lives simpler and save them money,” said Sullivan.

Tajir (who declined to interview for this story), also has a very positive VC story: it’s the first startup from Pakistan to be backed by the YCombinator, quite possibly the most famous startup accelerator in the world. Its latest round of financing includes Pioneer Fund, Golden Gate Ventures, Fatima Gobi Ventures, Karavan, and VentureSouq. Since 2018, the startup has amassed 15000 retailers in the greater Lahore area.

Bazaar declined to say how many retailers they had gotten on board, but did reveal that they now had 20 core team members, recruited from different consumer goods manufacturers, Swvl, and Careem.

The automation expert

If Bazaar and Tajir are looking to change the relationship between mostly distributors and retailers, then the company Salesflo was looking at a different part of the puzzle: how to smoothen the relationships between manufacturers and distributors/ retailers.

Salesflo, which was founded in 2015, is the brainchild of Yasir Memon and Sharoon Saleem. Memon graduated from LUMS and Saleem graduated from GIKI, and both joined Unilever as management trainees a few years apart. Memon stayed there for the next eight years, until deciding to venture out with Sharoon to form Salesflo.

Salesflo is a SaaS, or Software as a Service, company, and sells software to manufacturers to help automate their processes.

As Memon put it, when manufacturers would reach out to stores to book orders, they would typically use paper and a pen to note it down. “So our software basically allowed them to have a mobile app on the device and they would send their sales team to go and collect orders on that mobile app from these stores. And for the entire inventory management, the logistics management, the dispatch management cash collection, everything would be done on that software.”

The process of automation was so successful that Salesflo was able to attract big fast-moving consumer goods manufacturers (FMCGs) like Nestle and FrieslandCampina Engro Foods in Pakistan. Smaller companies were switched over from paper and pen to automation, while larger companies were switched over from a previous legacy system to a more analytics focused system that supports augmented intelligence (AI).

This approach also seeks to reduce inefficiencies as well, but is less disruptive than the other companies. In fact, Memon does not mince words when it comes to talking about Tajir and Bazaar, calling their models unsustainable in the long term. His experience working with manufacturers as ‘clients to please’ has given him some perspective about how to tackle the supply chain.

“Fundamentally we’ve seen this in multiple markets that whenever Tajir and Bazar type of model comes in, manufacturers basically tend to blacklist the specific marketplace that tries to disrupt their model. A number of manufacturers blacklisted Tajir, I don’t think Tajir has any terms with any of the manufacturers right now,” he said.

He is also wary of trying to eliminate distributors or curtail then, noting that these are full-fledged large organisations that are quite automated.

And yet, in August 2019, Salesflo started Jugnu, an app that does pretty much exactly what Tajir and Bazaar do. Their justification? Well, they had already spent a significant amount of time maintaining good relations with manufacturers.

“We’d already done the plumbing work for a lot of manufacturers. And if we can now give the capability to the retailer to be able to place an order to the manufacturer, the manufacturer can choose if they wanted to service it through a distributor, if so, which one they want to service through, and if they want to service it to some indirect wholesaler.” said Memon.

The advantage that Jugnu claims to have over the others is the close link with manufacturers. And it seems to be working – the platform has roughly 12,000 retailers on it, and is present in Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad, Gujranwala, Sialkot, and Kasur.

Adoption

So which business model is likely to succeed? And are they likely to bring the disruption that they claim they want to in the industry? Some examples from other countries might help provide an answer to those questions.

Let us take China for instance. There are at least five parties which make sure that the whole tech-enabled value chain works. There is a company that owns the B2B marketplace platform, then there is a company that owns the physical stock, then there is a company that owns brands and marketing spending, there are companies which do last mile deliveries and then to top it off and maybe the most crucial, are companies that take care of the financial payments.

But, even in China, it involves a lot of handholding, handshakes in the middle to make it seamless. For successful adoption of the B2B model, you would have to integrate on many ends, in a holistic ecosystem.

In Pakistan, and in this very space, credit sales are prevalent. A retailer would not make upfront payments to a distributor, rather a necessity that it is bought on credit. Critical questions arise as to how will that be catered through the tech? Who will extend the credit? Who will be responsible for the credit? Needless to say, the app owner, the manufacturer and distributor are varying parties, so who takes the risk?

For anyone trying to digitise this space, it is pertinent to understand the reasons for doing so. Is it well and truly an attempt to make a difference; to increase efficiency in the supply chain; to facilitate competitive pricing and to harmonise the players or is it to rid the market of the middlemen i.e. distributors and wholesalers. If it is the latter, it shall be nothing short of a call to war.

Disrupting the status quo in any field is a massive ask but taking on the distribution bigwigs, some of whom, bigger than basic manufacturers, with their pools of resources, government and political connections, army of labourers, fleets of transport, diverse channels of supply, and piles and piles of stock, would be a different challenge altogether. Most of these distributors have worked in this space for decades, know it like the back of their hand: its nooks and corners, its mentality.

It is an issue that Memon is aware of: “The distributors, the retailers, the market has been working in a set way for not years but decades. So it will be a constant hampering, telling them again and again what they need to do, how they need to go about the process and the benefit they are going to reap out of it eventually.”

Firstly, in order to stand up to the system these companies would require much more cash than they have raised or may raise in the not too distant future. It would require a long-term systematic plan to integrate the space and its players in order for it to be a nationwide change. As of now, it remains unclear the extent to which these companies will be able to scale their operations nationwide.

Another competitive pressure will come from prominent manufacturers and distributors themselves. While these young companies were launching their apps to rid the world of its tiring inefficiencies, the manufacturers and distributors too have started to digitise and technologically improve their businesses and the ecosystems they exist in.

An example of which is the app launched by Unilever for direct procurement by retailers. Profit has learnt that this app improves the retailer experience through enhanced ordering, sales, marketing and payment systems. An app which simplifies and facilitates ordering for the retailers, deliveries by the distributors and payments for all parties: a glimmer of what a harmonised, holistic tech ecosystem for the retail supply chain might look like.

Ultimately, whether it is about automating the supply chain, or disrupting the distributor model, for any app to be successful, the retailer will have to adopt the technology. Islam Sahab seemed a little cautious about using any app. “I have built relationships with distributors for over 16 years. They help out in circumstances, get things like paint, or signages,” he said.

His colleague manning the cashier was more brutal. “Everyone these days is making an app. I get messages from these places: try this, try that.”

Any tech or VC jargon of ‘disruption’ companies will fall flat, if retailers like Islam Sahab are not adequately convinced of the end product. The three startups have all amassed curious and frankly, brave, retailers. Let us see if they can retain them.

What a fantastic article. As one of the player in B2B category, I am amazed of how detailed you have explained this. Speak my heart out. Thank you

Great explanation of the business model these startups are trying to disrupt and risks which they face.

Would love to read a follow up article now after an year has passed, with B2B tech space even more crowded with Retailo and Dastagyr also joining Bazaar, Taajir and Jugnu.