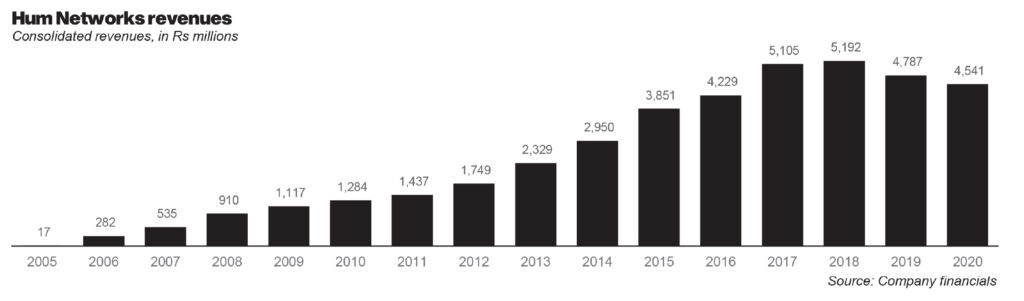

There are no two ways to say it: Hum TV is Sultana Siddiqui’s baby. Yes, she raised the financing from investors including her brother Jahangir Siddiqui – the veteran, and now retired, investment banker – and yes, her daughter-in-law Momina Duraid is a key figure in the creative direction taken by the company, and her son Duraid is the CEO. But when it comes to Hum TV, everyone knows Sultana gets the last word.

But, if the rumours in the market – and the astonishing movement of the company’s stock price – are any indication, that may not be true for much longer.

There appears to be a concerted, well-financed effort to seize control of Hum Networks – the parent company of four major Pakistani television channels including Hum TV (local entertainment), Hum Sitaray (hybrid local and foreign entertainment), Hum Masala (food and cooking), and Hum News.

How do we know this? Hum Networks’ stock price has shot through the roof, and some of its existing foreign shareholders have acquired an even larger stake in the company, implying a desire to take control over the company’s board of directors, if not the management itself.

Should the changes be pushed through, it would the culmination of a saga almost as dramatic as the television shows that air on the company’s flagship entertainment channel. Unlike those shows, however, this drama has the virtue of playing out in real life.

The share sale, and the stock price run-up

On June 5, 2020, Hum Networks sent a disclosure notice to the Pakistan Stock Exchange: Kingsway Capital – a London-based asset management firm – had bought 16.5 million shares of Hum Network at Rs8.90 per share, valuing the transaction at nearly Rs147 million (about $900,000). The shares represented about 1.7% of the total shares outstanding of the company.

Kingsway already owned 16.3% of Hum Networks, so adding a little more to its holdings was not necessarily out of the ordinary, or even newsworthy. Here is what makes it significant, however: prior to this transaction, a consortium of 15 foreign investors owned about 48.6% of the company. Add in this amount and the foreign investors now own 50.3% of Hum Networks, enough to have a majority share.

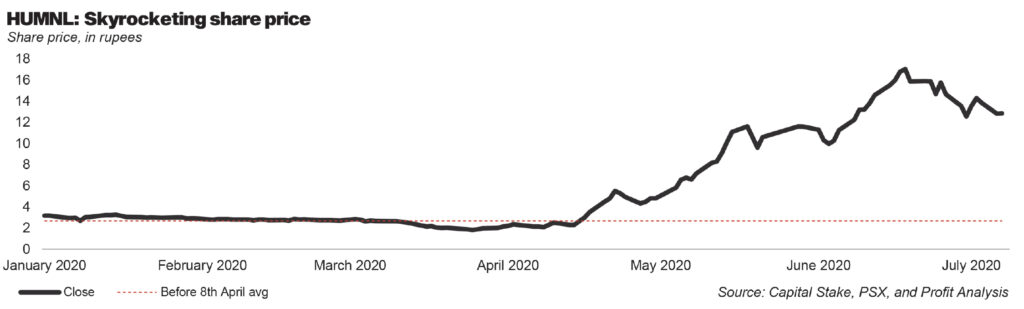

That this change took place against the backdrop of an extraordinary run-up in Hum Networks’ share price – the stock jumped from Rs1.82 per share on March 25 to Rs10.26 the day before the Kingsway announcement, an astonishing rise of 463% in just over two months – and the move starts to look like the prelude to something more serious.

And then there was the massive rise in trading volumes. Prior to April 15, 2020, the average number of shares traded in Hum Networks was around 258,000 per day. Between April 15 and July 7, however, the average trading volume in the company’s shares jumped to 5,767,000 per day, an increase of 2,135%.

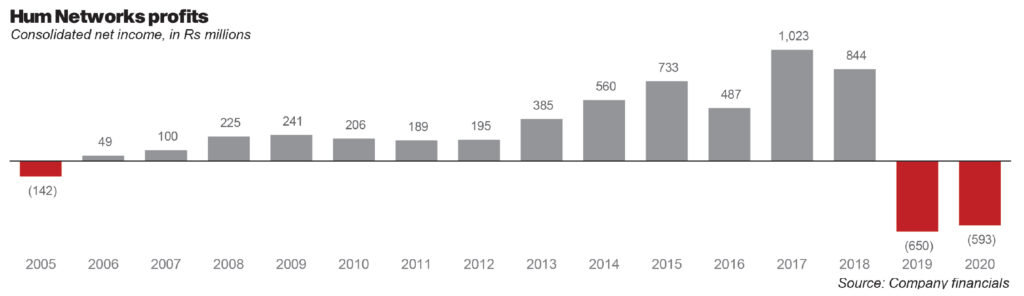

None of this is justified by the company’s recent performance. The most recent earnings announcement came on April 30, 2020 for the nine months ending March 31, 2020. While the numbers were slightly better than the previous quarter, they were hardly anything to get this excited about.

For the first quarter of 2020, revenue was up an impressive 21.8% compared to the same period last year, and the company managed to swing from a loss to a profit. However, that increase in quarterly revenue was not enough to reverse the otherwise dismal performance of Hum Networks. Revenue for the nine months ending March 31, 2020 (the first three quarters of the company’s financial year) was still down 8.3% compared to the same period in the previous year.

That result announcement justifies some of the optimism, to be sure, but hardly the kind that justifies the stock price jumping as high as it did, nor the kind of volumes that rose as high as they did.

So, what exactly is happening with Hum Networks? Why are so many of its shares trading hands, and why are investors so excitedly bidding up the price of the stock?

Before we explore the answer to those questions, let us add in two more ingredients to this drama: Sohail Ansar, one of the independent directors of the company sold 582,000 shares – nearly all of the shares he owned – in 18 transactions on June 9 and June 11, at an average price of Rs13.70 per share. All told, Ansar’s share transactions resulted in him receiving nearly Rs8 million. It is unclear if Ansar made a profit or loss on his investment in the company’s shares.

And then came one more wrinkle: on July 6, the company once again wrote to the PSX and informed them that the share registrar of the company – the entity that actually holds the records of who owns how many shares and when they transacted – would be changing from the Central Depository Company of Pakistan (CDC), the most widely respected registrar in the country, to FD Registrar Services, a much lesser-known provider of such services.

All of this reeks of a battle for control of the company. So how did we get here?

Who wants to control Hum?

Let us first settle the mystery question: who would have an interest in wresting control of the board of directors of Hum Networks and why?

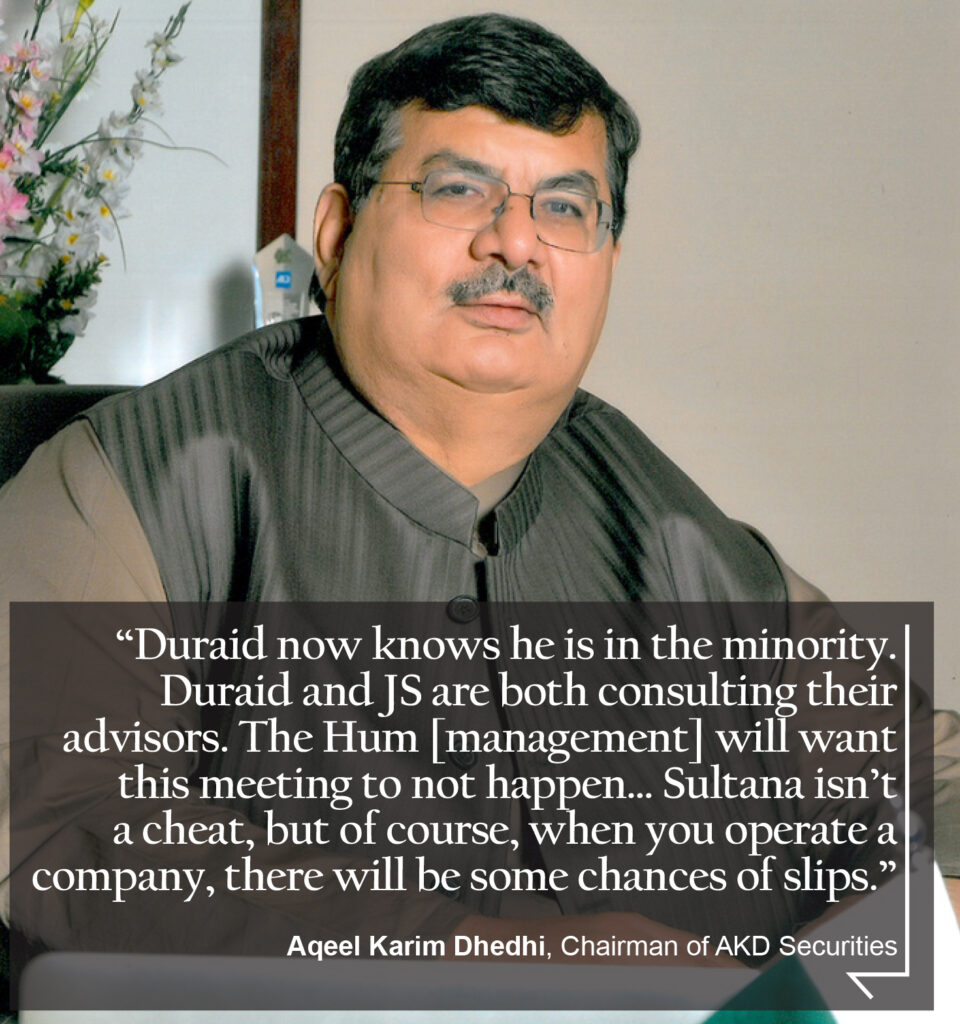

Aqeel Karim Dhedhi, the highly influential investment banker and stockbroker known throughout the market by his initials AKD (also the name of his firm), thinks he knows who is behind it: “Jahangir Siddiqui just wants to bring Sultana down,” he said in an interview with Profit.

He even has an elaborate theory as to how and why Jahangir Siddiqui would want his own sister ousted from the company that represents her life’s work and pinnacle of her professional accomplishments.

As reported in a previous story in Profit, Sultana had started the network with the financial support of her brother, but had built it up into a successful enterprise on the strength of her own talents. In recent years, however, there had been a falling out between the two siblings. The reason is somewhat unclear, though AKD thinks he knows why.

The issue, he thinks, started in 2012, when Sultana Siddiqui and Momina Duraid – her daughter-in-law – both bought houses in the United States. “The main question [Jahangir had] was where Sultana got the money to buy the house,” said AKD.

The dispute arose from the nature of the company and the complex financial arrangements that Hum Networks has with Moomal Productions (now called MD Productions), the main production company from which it buys its content. Hum Networks’ business model relies on that relationship. Here is how.

Television is a difficult business because you have to keep producing shows that have audience appeal. Unlike shows in the US and UK, where good shows often run for multiple seasons, Pakistani shows are effectively all designed to be single-season shows of varying lengths, with one story arc dominating the entire season and the show concluding when that arc ends. That means there is much higher turnover in shows, and therefore much less predictability in terms of whether or not a channel will be able to produce content that people will like.

It also means more financial instability for the actors, producers, directors, scriptwriters, and other staff who are involved in the production of television shows. They do not know where their next paycheck will come from once the show they are working on ends.

Hum Networks succeeded by attracting the best talent, which it did by solving the financial insecurity problem for people who work in the television business. In addition to the publicly listed Hum Networks, Sultana and her family also own Moomal Productions (now renamed MD Productions), a private production house that have an exclusive contract to produce content for Hum TV, the company’s main entertainment television channel.

Because they have guaranteed uptake of their shows, Moomal has a habit of granting multi-show or multi-film contracts to actors, directors, writers and other talent. Thus, even though shows last for a single season, Moomal is able to hire people for longer, giving talent more predictability and Moomal (and by extension, Hum TV), the ability to attract some of the best talent in the industry.

And this strategy has largely worked. The dramas it has produced have generated an audience beyond Pakistan and the company syndicated the 2011 show Humsafar, its biggest hit drama and the biggest ever in Pakistani television history, to an Indian channel. Humsafar generated Rs200 million for the company in revenue on its first television run, the highest for any Pakistani television show until that time, and in the syndication deal, it earned even more.

The downside of the strategy, however, is the potential for financial conflicts. While all the public company’s shareholders own the television channel, only Sultana and Momina own MD Productions. But Momina’s husband is the CEO of the company that decides how much MD Productions gets paid for its shows. And the minority shareholders of Hum Networks – including, back then, Jahangir Siddiqui – have no visibility into the finances of MD Productions.

That means that Duraid can agree to buy a show or film for an unreasonably high price from MD Productions, knowing that the excess profits will flow to his wife and mother. That high price, however, means a lower profit margin for Hum Networks, the publicly listed company in which Jahangir Siddiqui then had a share.

It was exactly this potential for a conflict of interest that – according to AKD – Jahangir was angry about in 2012 when he demanded to know where Sultana and Momina got the money to buy a house in the United States.

Sibling rivalry

The fight grew heated enough that outside arbitrators were involved. The initial two arbitrators were Bashir Janmohammad (one of the major shareholders of Dalda), and Arif Habib, another investment banker, and industrialist who is the controlling shareholder in the eponymous Arif Habib Group.

In AKD’s telling of the story, Sultana conceded that the houses were indeed bought from the proceeds of the profits from Moomal Productions, but suggested that the profits were legitimate. Jahangir, however, found the arrangement to be untenable, and demanded that the production house be moved inside the publicly listed company so that all shareholders could share in its profits, not just Sultana and Momina.

The arbitrators, however, disagreed with Jahangir’s position and insisted that Sultana had the right to continue owning the production house independently. Jahangir was deeply upset at this result, and then suggested what is known in market parlance as man mela: a price is set for the company and whoever has the capacity agrees to buy the other party’s shares outright.

That may have resolved the problem, but – AKD says – Ali Jahangir Siddiqui, Jahangir’s son and heir stepped in and insisted that they be a forensic audit to determine how much money has been siphoned out of Hum Networks before the man mela could take place. Arif Habib suggested a compromise, suggesting a regular audit by one of the Big Five accounting firms in Pakistan.

Ali disagreed that such an audit would be sufficient and insisted on a forensic audit. Since then, says AKD, Jahangir and his son have been trying to seize control over the company.

Is this JS, or just corporate governance?

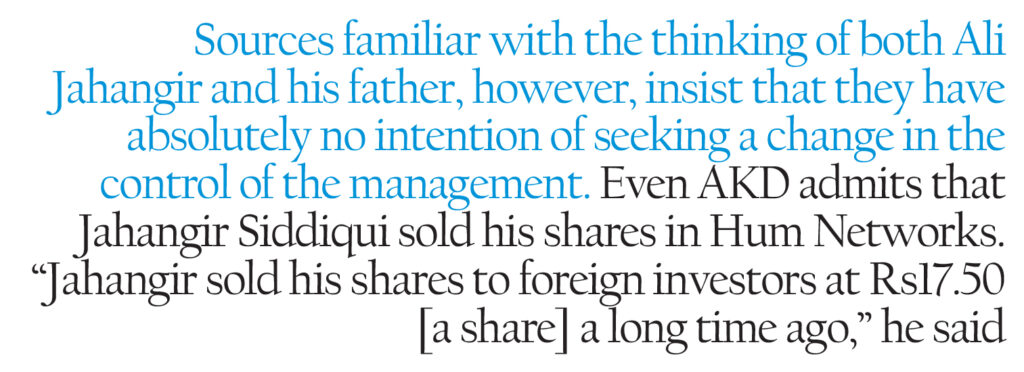

Sources familiar with the thinking of both Ali Jahangir and his father, however, insist that they have absolutely no intention of seeking a change in the control of the management.

Even AKD admits that Jahangir Siddiqui sold his shares in Hum Networks. “Jahangir sold his shares to foreign investors at Rs17.50 [a share] a long time ago,” he said.

However, even though JS does not appear anywhere in the shareholder list, AKD insists that he wants to take control over the company. “When Kingsway got upset at Hum, Jahangir got them to be his proxy,” he alleges.

To be clear, what AKD is suggesting – while theoretically possible – does not actually make any sense. For instance, let us suppose that the foreign investors really are seeking to control the company on Jahangir’s behalf. However, even if they control more than 50% of the shares, they can still not seek an ouster of the management. Under Pakistani law, removing a CEO requires not a majority but a supermajority of 75% of the shares of a company. And the CEO has complete control over who else is in management.

Duraid and his brother Shunaid control 29.4% of the company, which means that unless Shunaid decides to back Jahangir Siddiqui – a highly unlikely prospect given the recent animosity between the two families – there is no way any group of investors can remove Duraid as the CEO.

This is exactly what sources familiar with the Hum Networks’ management tell Profit: that they believe there is no way to effect a change of management control and hence they remain unconcerned about the activity in the share price of the company or the new shares being bought by the foreign investors.

Based on the data Profit has reviewed, and what we know of Pakistani securities and corporate governance laws, the case AKD is making – that Jahangir Siddiqui is out to ruin his sister and seize control over her company – does not appear to be backed by the evidence.

What is clear, however, is that the objections raised by Jahangir and Ali Jahangir are shared not just by them, but by the foreign investors who bought out their shares.

Moving MD Productions in-house… maybe?

The foreign investors to whom Jahangir Siddiqui sold his shares ended up demanding exactly what Jahangir had been demanding all along: that the production house now know as MD Productions no longer be a separate entity and instead become a wholly-owned subsidiary of the publicly listed company into which they were buying shares.

In other words, what Jahangir was demanding had been in accordance with globally recognised good corporate governance practices, a demand that Sultana, Momina, and Duraid has to accede to anyway when they asked Jahangir to exit the company.

However, it appears that – even though they promised the foreign investors that they would do so – Sultana and family have not actually gotten around to moving MD Productions in-house to Hum Networks, despite it having been more than four years since they first committed to having done so.

The Hum Networks board first approved of the merger of MD Productions with Hum back in September 2016. In April 2019, however, the company withdrew its application for the merger from the Sindh High Court – “due to inordinate delay in the matter proceeding with the High Court,” they said in the 2019 annual financial statements.

That statement, however, sounds odd. The Sindh High Court is known as the most corporate-friendly court in the country. Halting or even delaying mergers and acquisitions transactions without cause is uncommon. Given the fact that this was a merger that the management of both companies were not particularly keen on to begin with, we suspect – though cannot confirm – that there are other reasons for why the merger was never completed.

Nonetheless, it appears that the Hum Networks management have not entirely given up on the matter. On February 28, 2020, they announced that they would try once again to have the merger go through. It is unclear what stage the merger is at, and the extent to which the management has had a change of heart on the matter. One thing is clear, however: if the merger does not go through, the foreign investors are likely to have one more reason to be upset with the management.

The share registrar change

Then we get to the shady business of changing the share registrar. Sources familiar with the management’s thinking state that Duraid and Sultana are not worried about a change in the shareholding of the company, and yet they made a move to change the share registrar from the CDC – the most widely respected registrar in Pakistan – to FD Registrar Services, a single-member private company that does not even have a website.

The move is seen as highly suspect by the foreign investors, particularly Kingsway Capital, who have made the unusual move of explicitly opposing the shareholder resolution required to approve the change. The motion to change the registrar will be presented at the extraordinary general meeting of the shareholders, announced for Saturday, August 22, 2020.

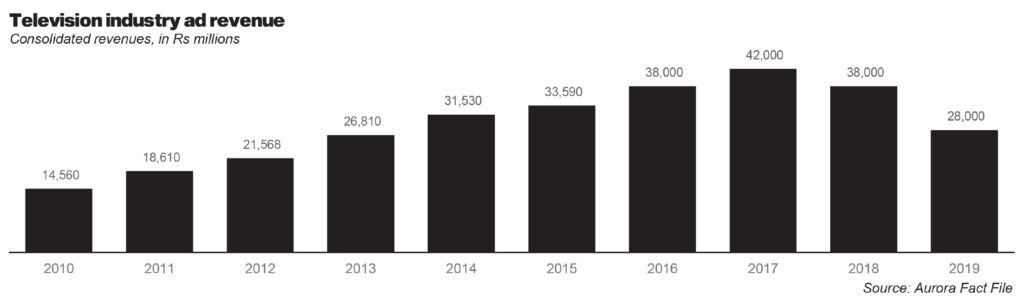

Why would Hum Networks want to change their share registrar? Well, for one thing, the CDC is among the more expensive registrars, and the management have stated that they want to cut back on costs, given the declining revenues of the company.

However, the costs of the registrar’s services are so immaterial that they do not even show up as a separate line item in the company’s detailed financial statements for 2019. So why change registrars? Well, if you are worried about who owns your shares, and you decide to change the entity that records who owns which shares from a well-reputed entity to a no-name company without even a website, one might forgive the foreign investors for thinking there is potential for foul play.

“Duraid now knows he is in the minority,” said AKD. “Duraid and JS are both consulting their advisors. The Hum [management] will want this meeting to not happen.”

Tellingly, he added the following sentence: “Sultana isn’t a cheat, but of course, when you operate a company, there will be some chances of slips.”

What comes next?

Even though AKD remains convinced that JS is making a move to take over Hum Networks, it remains unclear as to how he might be able to do so at all. On the other hand, there do seem to be some visibly upset foreign institutional shareholders who have made their displeasure with the Hum management known in no uncertain terms.

Meanwhile, one of the announcements that came through as part of the notice for the extraordinary shareholder meeting: Sultana will finally be retiring as a director of Hum Networks, perhaps choosing to relinquish control to the next generation while she can still leave on a positive note.

And while the foreign investors do not have enough votes to oust the management, they do seem deeply unhappy, a situation that is unlikely to remain tenable for long.

I was one of the ardent supporters of HUM TV

)when Sultana Appa had strong control over the quality of Drama content and message it use to convey to our society. Unfortunately third rate topics of Dramasp picked from flop Indian pTV industry are displayed focused at three main themes such as magics, detretrioted family relationships not acceptable unde our culture r any normal standards provoking or legitimizing such relationships in families….cannot even want mention here. Just for Business ratings

What’s the content of HUM TV dramas? Detroit viewers ethics and moral values. This channel should always make rating as PG18+. Though unfortunately after HUM TV dramas content, now same content being adopted at other channels.

I’m convinced that unfortunately Hum tv aired so filthy dramas that only destroyed our social and religious norms, misguided and lured the young generation specially the innocent girls. Hum tv, it’s owners, writers, directors, producers, actors and all para staff must must feel ashamed for showing publicly illecit relations between girl and her father in law, a girl and her sister’s husband and a married woman and her husband’s friend. Even in the open European and American society it doesn’t and can’t happen. All these vulgar people are fuel for hellfire. They need to feel ashamed and this wretched woman Sultana siddiqi is Don and iblis of all these people and the اسلام enemy hum channel. If it were in Saudia Arabia all of them should have been hanged much earlier. They have caused an irreparable damage to our homes, boys and girls and the society. They don’t fear God at all and neither they believe in Resurrection.

The financial statements of Hum Network Limited for the year ended 30 June 2019 disclosed MD Production (Private) Limited as a related party. Total amount of the transactions will MD Production was Rs. 1.3 billion during the year. Transactions with related parties is a very sensitive issue and SECP closely monitors such transactions. These transactions must be carried out under arms length in accordance with the provisions of Section 208 of the Companies Act, 2017 and the Companies (Related Party Transactions and Maintenance of Related Records) Regulations, 2018; Otherwise related party transactions are put before the Shareholders for approval. I have reviewed AGM notice. It does not include any agenda item for the approval of related party transactions. I request the writer to revisit the article, because it misleads. If frivolous information is really necessary to be included in the article, she must have also discussed law of the land in detail though she hinted about it.

The senior finance management are born fraudsters who undertake fraudulent transactions within the Group companies; fake companies are made to transfer profits, transfer pricing issues etc. Shame on stock exchange & Big 4 Auditors that such activities are being carried out in listed Companies and they are sleeping. The financial statements are manipulated; shame on their auditors who call themselves Big 4; they are also unable to identify any such transactions as they are more concerned with the Business.

It is quite astonishing to believe that it is a listed Company.

the corroboration that the CFO is born fraudster can be judged from the fact that the share registrar has been changed from CDC to another less creditable organisation in July 2020; when shares started to move. This was probably done to make frauds with other shareholders and manipulate the shareholding.

Duraid and Sultana both are fraudsters; they have allowed maximum manipulation in FS of their group companies; it is quite astonishing how the laws in Pakistan operate as a family owned business is making Billions of Rs. in frauds and there is nobody to challenge or question it.

She is Ekta Kapoor of Pakistan and ruled Hum Network and influenced many other media channels

Whatever viewer or reader says, it’s an excellent article

Accidently I read the research article of Ariba Shahid. Indeed it is a great work and very informative for me. I knows the name of AAPA Sultana Siddiqui since she joined PTV in early 70s. No doubt She is a legendary figure in Pakistan.

I want to be a actor. Please help me

Please aik acha actor banna ma Mari help Kara plz

I want to meet you. Please send me address.

Sultan ap is the best lady In the Pakistan shobiz

I need your help ma’am and Duraid Sir pls