It is a simple enough story and almost nobody in the government – and even some people outside of government – seems tired of telling it: the Pakistani economy was on its path to recovering from the 2018-19 recession when it was struck hard by the lockdowns induced by the coronavirus pandemic, leading to a short, sharp recession. But the government swung into action with a fiscal stimulus, regulatory incentives for investments in some sectors, and looser macroeconomic policy, and the recovery has been just as rapid, at least insofar as industrial activity is concerned.

The problem is that the last bit of that story – the part about low interest rates being part of the stimulus that has led to the economic recovery – is not entirely supported by the data. And that has significant consequences, because if that last bit is not true, then a lot of Pakistani macroeconomics needs to be rethought.

Why, you might ask? Because most of macroeconomic theory assumes that governments do not behave like cocaine addicts. And if, as in the case of the Government of Pakistan – specifically the Finance Ministry – a government does behave like a cocaine addict, macroeconomic models break down and if one’s policy decisions are based on those models, one will end up making the wrong decision.

What we will tell next is the story of a cast of characters – each behaving rationally, given the constraints they are operating under – and every single one of them contributing to a most irrational state of affairs.

Here is our central thesis, based on an analysis of banking sector data from the State Bank of Pakistan and other macroeconomic data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics: the effect of monetary policy on lending – and therefore economic growth – is very limited in Pakistan, in large part because the government is the dominant borrower that crowds out the private sector.

That much is well-established, including by research conducted by economists at the State Bank itself. It is also established that monetary policy has little to no influence on the government’s willingness to run large budget deficits.

So, if we are saying that monetary policy has little stimulative effect on the economy, some influence on inflation (but less than in other economies), and has no impact on the government’s willingness to borrow, what is it good for? Why not permanently set interest rates low so that industries looking for loans face a low financing cost and thus are able to borrow more and grow faster?

Many, many reasons why.

In this story, we will first lay out how and why the government of Pakistan became the dominant borrower of the financial system, then lay out how that completely cripples the ability of the State Bank of Pakistan to use monetary policy as an instrument of economic policy in Pakistan, followed by an explanation of why, despite their lack of effect on lending, the central bank should not adopt a policy of permanently low interest rates (you would think we would not need to say this, but this tends to be one of the most consistent demands of every business lobby in Pakistan.)

How the government came to dominate borrowing

At one level, this is a simple story: the government of Pakistan has simply failed to get its fiscal house in order through poor enforcement of tax laws and as a result runs massive fiscal deficits. The borrowing needs of that deficit are so high, that the government now accounts for a majority of the lending in the banking system.

But, of course, the simple story tells us absolutely nothing useful. The more relevant questions to ask are why the government of Pakistan has gotten to this point. Because if we stop the story at “the government simply is not doing its job”, we assume the problem is corruption, or incompetence, or some combination thereof. The more fleshed out story, however, will reveal that the problem is one of incentives.

Here is what has now been happening more or less uninterrupted since the late 1980s in Pakistan: a new administration comes into office and the civil servants who constitute the more permanent fixture of the government decides it is time to tell them the truth. The truth is usually that the previous government was painting a rosier picture of their record than the reality, and that the country’s finances are in bad shape.

At that point, the new administration – whether it be an elected politician, or a military dictator – has a choice. They can announce the corrected numbers (in one fashion or another, most governments in Pakistan end up doing that), and then either adopt policies that would fix the problem over the long run, or they can adopt policies that will win them the next election. Nobody has yet seemed to figure out one set of policies that will do both.

(Side note: Pakistan has had authoritarian dictatorships, but not totalitarian ones, which means even our dictators do not exercise absolute control and – at one point or another – have had to contest a semi-fair election. There are many, many implications of what that means, but this publication will leave those to experts who understand these subjects better than we do.)

The government’s first option is that it can crack down on tax evasion and try to implement taxes on currently untaxed portions of the population which will result in no growth in tax collection in the short run but may increase collection in the long run, with no guarantees of success.

In the meantime, the government will have no means of dealing with the short-term collapse in the country’s foreign exchange reserves, which will mean that the rupee will keep depreciating. Given Pakistan’s reliance on imported energy – in the form of both oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG) – the country will face higher inflation if the currency keep depreciating.

The second option is to let the civil servants who run the finance ministry and the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) run the tricks that they do in order to increase tax revenues in the short run. The ability to quickly raise revenues allows the government to show international lenders like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) that it is doing better at managing its finances, which allows them to access foreign borrowing. That foreign borrowing allows the rupee to remain stable.

Keeping the rupee stable allows the government to brag about low inflation, since inflation in Pakistan is tied to energy costs. Low inflation – governments seem to believe – will help them win re-election.

Needless to say, every government – both civilian and military – has chosen option number two. You can see why it is the rational choice for them. Option one is better for the country in the long run, but there is no guarantee of success and, in any case, any administration simply does not have the kind of time that it would take to implement that long-term fix. They will be in the middle of a re-election campaign long before then.

Why do the civil servants offer this option, though? After all, the whole justification of having a permanent civil service who cannot be fired (only transferred) is that they are supposed to help the cabinet and the prime minister think long term. Well, if your power within the civil service is predicated on how much the prime minister or the powerful cabinet member relies on you for advice, then it is in your best interest to deliver advice to them that they will perceive as helping them win re-election.

Nobody ever got fired or transferred in the civil service for not suggesting ideas that would help the country’s economic progress in the long run.

So, both the politicians (and military dictators) and the civil servants are behaving in a manner that serves their own interests, but one that ensures that – in the long run – Pakistan’s economy remains mired in one chronic fiscal and external account crisis from which we have struggled to escape. That is not a problem of corruption, or incompetence, but one of incentives. And it is a problem that remains constant, regardless of whether we switch to a military dictatorship or a democracy.

At Profit, we have covered the implications of the obsession with the rupee before. In this story, however, we will cover what this means for the Pakistani banking system and for monetary policy.

The government as a dominant borrower

The problem with choosing option two, outlined above, is that it is a bit like taking cocaine when you are very tired and need to work. Yes, the drug will give you an energy boost and you will be able to keep going longer, but now you have a different problem: you are a drug addict.

The same is true of the government of Pakistan. All those tricks that the FBR uses (those withholding taxes you pay on your cellular credit and bank transactions are two examples of such tricks) to increase tax revenue work in the short run, but do not actually help reduce Pakistan’s budget imbalances in the long run, which means that the government’s budget deficit never really goes down in any sustainable way.

Running a budget deficit means the government needs to borrow to pay for its expenses, which it does by issuing bonds. In theory, the government of Pakistan is open to selling those bonds to anyone, and indeed, though National Savings, it sells them directly to individuals as well. But given the dominance of the banks in Pakistan’s financial system, the bulk of the bonds it sells are bought by the banks.

Given just how long the government has been running these deficits, and how large they are relative to the size of the economy, over time, the banks’ lending to the government has reached the point where it now constitutes a majority of their total lending portfolios. Government borrowing became a majority of total borrowing in the economy in the second quarter of 2011, and has effectively stayed the majority since then.

The State Bank has noticed that trend and has used language that indicates that it considers the government’s borrowing to be a major macroeconomic problem. As far back as 2013, the central bank talked about ways to address the government’s borrowing and how it was confounding its ability to make monetary policy.

See, the problem is not just that the government borrows a lot of money. The problem is that the government borrows a lot of money and does not care what interest rate it pays to borrow that money.

In a working paper for the central bank quoted in its third quarterly report for fiscal year 2013, then the SBP’s Chief Economic Adviser Mushtaq Khan wrote: “Price signals often fail in structurally distorted economies. A desperate borrower does not respond to price signals; this is especially the case with addictive goods/services. While increasing interest rates is sufficient to deter an individual from borrowing more, in the case of a government with a short-term horizon, the rising cost of credit will not deter fresh borrowing, but only increase the government’s indebtedness and squeeze the fiscal accounts further.”

[Note that it is the State Bank that used the language about ‘addictive substances’. We simply added the ‘cocaine’ part. In our defense, the SBP started it.]

Why is this relevant? Because raising rates has historically been used by central bankers to wake up their governments to the inflationary impact of their excessive borrowing. By raising interest rates, and therefore the amount of interest the government has to pay on its debt, central banks hope to induce governments to reduce their borrowing.

But if, as in the case of the government of Pakistan, the government is behaving like an addict, then monetary policy’s impact on the fiscal situation of the country is virtually non-existent.

In such a situation, there have been many who argue the following: “if the State Bank cannot use interest rates to knock some sense into fiscal policy, why not reduce interest rates so that at least the rest of the economy can access capital at lower borrowing rates, which would then increase economic growth?”

That is just a flat-out terrible idea, not least because it effectively means giving in to the government’s worst habits: giving more cocaine to an addict. We have no idea what the equivalent of a government overdosing to death looks like, but we suspect it will not be pleasant. Actually, we do know: it is called hyperinflation, followed by swift economic collapse. (See Weimar Germany, Zimbabwe, and Venezuela for details.)

And then the supposed effect on the rest of the economy – even assuming we can avoid a catastrophic hyperinflation – is not good.

Specifically, here is our contention: given the role of the government as the dominant borrower in the banking system, lowering interest rates will have no material stimulative impact on the economy.

Why lower interest rates will not work to boost economic growth

We will caveat the following analysis by stating categorically that we do not claim to have made substantive findings, and that our research is merely what we hope is a useful starting point for a more robust analysis. These are simple, univariate ordinary least-squares regression analyses and a more multivariate approach is likely to yield findings that may differ from ours.

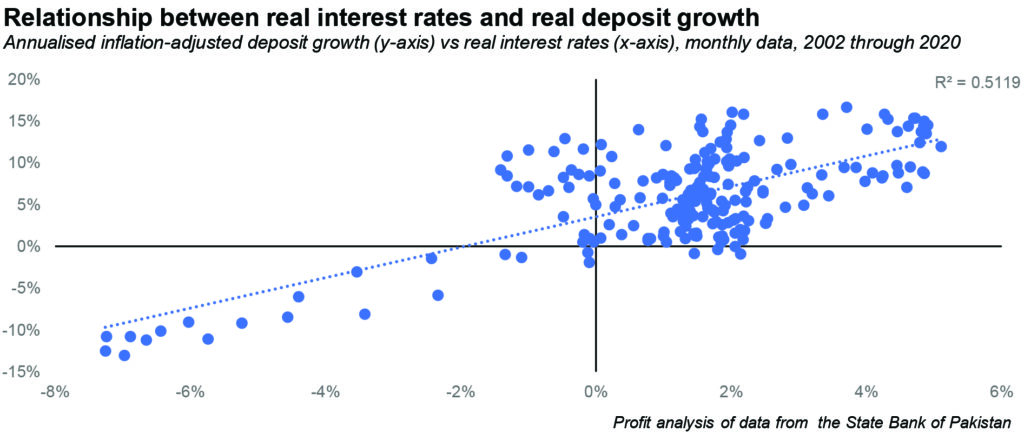

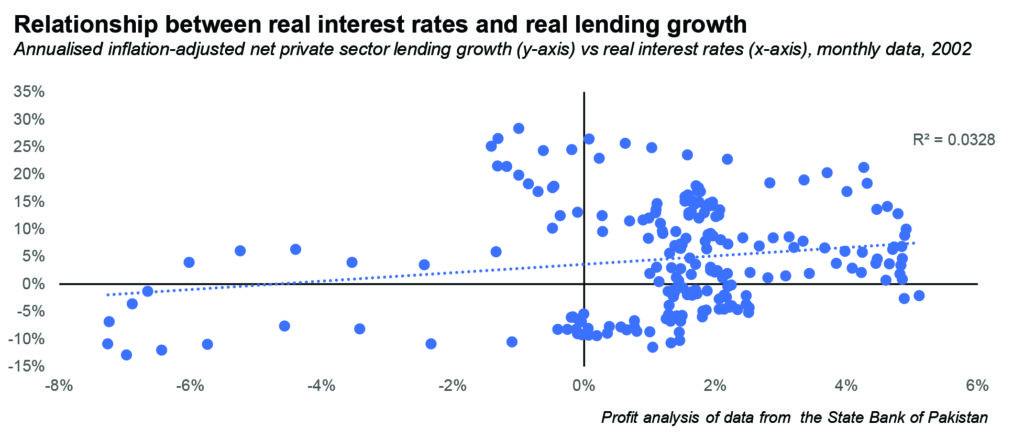

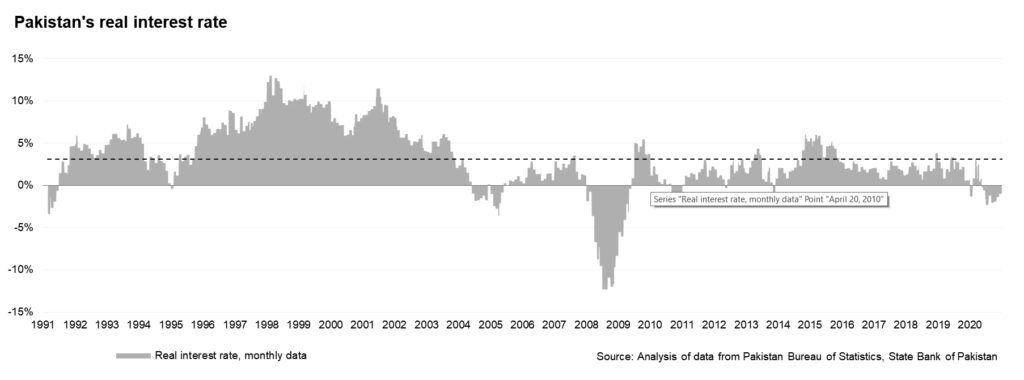

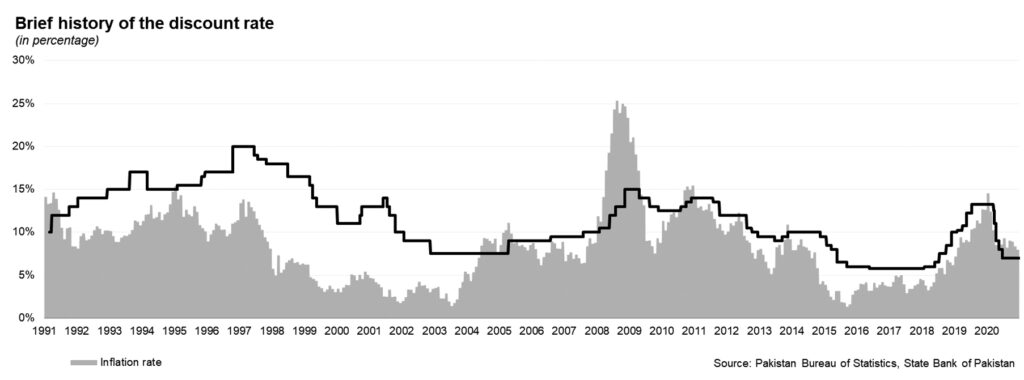

With that said, our initial analysis of deposit and lending data from the State Bank of Pakistan and inflation data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics indicates that when the SBP’s discount rate exceeds the inflation rate, there is a positive effect on deposit growth at the banks, but when the benchmark discount rate is below inflation, there is no material impact on private sector lending growth.

Before we dive into our findings, first a brief note on our methodology. We used real interest rates, which we defined as the trailing 12-month average of the State Bank’s discount rate minus the trailing 12-month average of the rate of inflation as measured by the national consumer price index (CPI). For both private sector lending, and for deposits, we used real – meaning inflation-adjusted – growth rates. Again, we used trailing 12-month averages for both. Adjustments for inflation involved geometric, not arithmetic subtraction.

We examined data from January 2002 through November 2020, with the data for each month representing the preceding 12-month period. This gave us 215 observations for the period in question. We then ran a single-variable linear regression of real interest rates against real deposit growth, and real interest rates against real private sector lending growth.

Why use private sector lending and not total lending? Because in order for monetary policy to have a stimulative impact, it needs to increase the private sector’s access and desire for capital to indicate that the economy is growing. If it only increases government borrowing, all it is doing is increasing the government’s willingness to borrow.

The effect we observe on deposits is exactly what we would expect to find: if real interest rates go up, so does the inflation-adjusted increase in deposits, meaning that deposits increase faster than inflation the higher interest rates are relative to inflation. This stands to reason: the better the inflation-adjusted returns banks can earn on their borrowing, the more they can pass on to depositors, which in turn will attract more depositors.

The effect on private sector lending, however, is less clear: there is a very weak relationship between real interest rates and inflation-adjusted growth in private sector lending. We would expect to find a negative relationship: the lower the interest rates, the higher the growth in private sector lending. Instead, we find a weak positive relationship, and a very low r-squared value (0.032), which suggests that real interest rates have very little explanatory power in determining the direction of growth in private sector lending.

Indeed, in the 42 months during which there were negative average real interest rates over the preceding year, exactly 21 were periods that saw positive inflation-adjusted private sector lending growth, and exactly 21 that saw negative inflation-adjusted private sector lending growth. In effect, when real interest rates are negative, there is exactly a 50% probability that private sector lending will increase, and a 50% probability that it will not. A literal coin-flip.

And this result stands to reason: if the government is the dominant borrower, accounting for the bulk of borrowing from the banks, the overwhelming bulk of new loans would go to the government, not the private sector.

There is also another reason this makes sense: if negative real interest rates decrease deposit growth, there will be a lot less new money for the banks to deploy into new loans, and in an environment where rates are low, banks will go for the option that will do the most to increase their return on equity, which in the case of the Pakistani economy means government bonds.

Why? Because government bonds do not require the banks to set aside any capital in order to invest in them. If Habib Bank wants to buy Rs100 billion in new government bonds, it needs to increase its capital base by precisely Rs0, but if it wants to increase its lending by Rs100 billion, it needs to set aside around Rs10 billion in either shareholder equity, or some other form of capital to be able to lend that much.

That means that any returns it earns on those government bonds will translate into a higher return on equity than any private sector lending. And that is before we even get into fact that there is a risk of defaults in private sector lending, but not in government lending.

What does all of this mean? It means that if the State Bank of Pakistan were to lower interest rates to below inflation, it would significantly decrease the growth in deposits in the banking system, but would not actually do anything substantive to increase the kind of lending that actually boosts economic growth.

So then why would the State Bank do such a thing at all? It would incentivise bad behaviour by the finance ministry, cripple the formal financial sector, and have no meaningful impact on economic growth. So the next time you see some industry lobbyist on television calling for lower interest rates, know that what they are calling for will help absolutely nobody but the addict. And probably not even the addict.

So, I think it is the best decision to making state bank an autonomous body.