Pakistan’s fledgling microfinance sector that never quite took flight is currently sitting on a ticking time bomb that could go off at any moment. Already a dwindling sector in the country, it has been further pushed against the ropes by the blows of inflation, interest rate hikes, and the heat of a global economic downturn.

Currently, the threat ready to implode at any point are loans at the risk of default — a situation originally triggered by the pandemic. While both the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) and the government have tried to provide relief and bail out the sector, the situation remains bleak.

In this article we explore how the major players are coping with the aftershocks of the pandemic and whether the sector is heading towards recovery or if difficult times have just begun?

Industry overview

The main investors in the country’s microfinance banks (MFBs) are commercial banks, Telcos, nonprofit entities/rural support programmes and specialised microfinance institutes.

The NGO-backed MFBs include the likes of NRSP Microfinance Bank Ltd, a subsidiary of the National Rural Support Programme, the Kashf Foundation as well as the Aga Khan Foundation’s philanthropy wing. The investments are an extension of the vision of these organisations; a vision based on poverty alleviation through financial inclusion.

The telcos adventure in the sector started after the SBP authorised the issuance of branchless banking licences in 2008. Telenor was the first one to do this when it joined hands with Tameer microfinance bank to launch easypaisa in 2009. Jazz followed them closley by launching Jazzcash in 2012. The telcos soon bought the majority stakes in these banks and rebranded them. Tameer became Telenor Microfinance Bank, Waseela was converted to Mobilink Microfinance Bank Limited (MMBL) while Rozgar microfinance bank was renamed as U Microfinance Bank Ltd, more commonly known as Ubank, after acquisition by the PTCL.

Commercial banks are also key players in the sector. The likes of HBL Microfinance Bank Ltd and Khushali Microfinance Bank Ltd (30% ownership of UBL) are examples of investment of conventional banks into the sector.

In 2020, however, this sector was jolted by the Covid-19 pandemic. Lockdowns halted business activity. Microfinance institutions provide small loans to a target audience that is not the most affluent in society. These are loans that could be provided to someone to open a shop for their trade such as to a barber or a carpenter. Unfortunately, these were exactly the people most impacted by the lockdowns with their small businesses being closed for months on end. This meant the microfinance sector was caught in a fix as the majority of its borrowers were not in a position to pay their loan instalments immediately.

How the sector responded to the pandemic

Immediately, regulators also realised that a crisis was brewing. The people that had taken these small loans were not expecting the pandemic and neither were the microfinance institutions. To try and stave off the rot that was setting in because of the unprecedented circumstance, the SBP decided to ease the pressure through the Debt Relief Scheme for deferment or rescheduling of COVID-affected borrowers through BPRD Circular No.14 of 2020. As per the scheme, the payment of loan principal could be deferred for up to 12 months if the borrower continues to service the interest amount.

The scheme also provided a restructuring option through which the outstanding principal and interest could be converted into a new loan altogether with revised terms and conditions. The programme remained valid up to 31 March 2021.

Though the relief was for the whole financial sector, the microfinance entities were the primary beneficiaries. “Out of 1.883 million applications received, banks, DFIs and MFBs have approved 1.825 million applications (96.92%) up to April 02, 2021,” As per SBP’s website.

“Since the launch of the scheme, individual borrowers, especially customers of microfinance banks, have been the major beneficiaries of the scheme. The restructured and deferred loans include 1.717 million approved applications of customers of microfinance banks involving an amount of Rs 121 billion, which approximately constitutes 50 percent of total net-loan portfolio of MFBs,” The website further stated.

For instance, Khushhali bank, the largest microfinance lender in the country deferred/rescheduled a loan portfolio of PKR 35.1 billion under the scheme, and HBL Microfinance availed the scheme for loans worth PKR 12.7 billion.

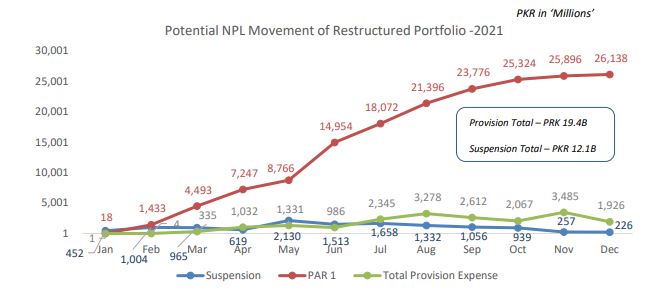

However, once the scheme expired in 2021, the sector started facing a fallout in the form of deterioration of portfolio quality. In simple terms, this refers to that portion of the total lending that is deemed to be recoverable.

“The industry started to see a declining trend in asset quality where overall Portfolio at Risk (PAR) 30 days crossed 6% during the year 2021. It is further anticipated that due to ever-increasing economic pressure, the non-performing loans may see a rising trend which is a key challenge for the microfinance sector for the year 2022,” said a statement in the Khushali President & CEO Review: Annual Report 2021, a report to the bank’s shareholders.

Yet, it must be noted that this wasn’t something the sector didn’t anticipate in the first place. Back in October 2020, the microfinance industry did a collective assessment of the liquidity crisis and reached a conclusion that one-fifth of the portfolio restructured under the SBP scheme is likely to default.

“Based on our assumption and calculations of 80% recovery from restructured portfolio and consequently 20% flow into NPLs, the industry is vulnerable to a risk of 41% erosion of its capital base,” states the internal industry working paper.

Source: Industry Working

Still, most MFBs did not provide for the amount to the extent the industry analysis recommended. For instance, HBL Microfinance Bank provided only 10 percent for the restructured/rescheduled portfolio. The rationale provided was that the bank had historically performed better than the industry average in portfolio quality, thus, 20% provisioning was not representative of the bank’s portfolio situation.

Furthermore, a significant amount pertaining to restructured/rescheduled loans was pending for recovery as at 31 december 2021. The aforementioned pending collections were 50 percent for HBL Microfinance and 96% for Ubank. However, for Khushali bank it was around only 17 but the figure is from a significantly larger base (approximately 29% of industry’s total rescheduling).

Future concerns — NPLs and the liquidity

Before we analyse the current liquidity situation of the sector, it is important to understand a few terms. There are two types of liquidity, the regulatory requirements and the simple cash liquidity (this is the amount you require for continuing business operations).

The regulatory liquidity refers to the Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) which banks have to maintain. Currently, a minimum CAR of 15% is to be maintained by the MFBs. The calculation of CAR is based on the capital held by banks divided by the aggregate of the bank’s risk weighted assets. As a rule of thumb, to improve CAR you have to decrease risk and increase capital.

Also, a term to remember is Subordinated debt. This is a debt that in case of winding up of the company has the last charge on the assets of a company (amongst all debt). Due to this characteristic, the debt is classified as capital when calculating CAR.

Now that we have a better understanding of the terms, let us take a look at the situation in the sector. The table below shows the CAR for some of the largest players in the market. The figures have generally been low over the past three years and when compared to the last five to seven years, the CAR has shrunk significantly for most players.

Capital Adequacy Ratio of MFBs

Source: Annual Reports & PACRA

To further highlight the situation let us take a look at two instances. In 2020, the CAR for HBL Microfinance was 15.1%, just above the statutory requirement. To enable this, HBL, the parent company of the bank, injected PKR 2 billion capital in the form of subordinated debt. Without this injection, the ratio would have fallen below the threshold to around 12.5%.

In the case of NRSP, the CAR threshold was breached in 2021 and the figure was between 11% to 12% as per sources. To avoid the wrath of the regulator, the bank assured an equity injection of PKR 1 billion from its parent company.

Disclosure in NRSP’s 2021 Financial Statements

Another player in the sector, Telenor bank, continues to face a deteriorating liquidity as it piles up losses while its sponsors, Alipay and Telenor, inject equity to keep it afloat. The combined additional equity invested in the bank for 2020 and 2021 is around PKR 19 billion with the latter year seeing an inflow of PKR 11.6 billion. (Read more about it in Profit’s article: Losses continue for Telenor Microfinance Bank)

As far as conventional borrowing is concerned, almost all the major MFBs saw a massive increase with the exception of MMBL. HBL MFB’s borrowing went from zero in 2019 to PKR 2.8 billion in 2021. Khushhali bank’s borrowings increased 977% between 2021 and 2020. While for NRSP and Ubank, the borrowings almost doubled and tripled respectively over the last year.

At the risk of diverging from the topic at hand, it is worth looking at the anomaly that is Ubank. This MFB is almost operating like a commercial bank. It has invested more in securities than it has lended (unusual for the sector) and it has massive borrowings, almost five to nine times the borrowing of other MFBs in the sector. The bank has miserably failed to recover the rescheduled portfolio as mentioned earlier and has high provisioning for delinquencies.

Yet, it was able to increase Profit-After-Tax for the year ended 2021 by 23%. If one takes a deep look at the financials, they will figure out that total comprehensive income has fallen for the bank as a result of unrealised losses on investment, ironically.

Furthermore, the effective tax rate for the bank was around 16%, lowest in the past five years. That is quite weird given the fact that the effective rate for the bank has usually been above 20%.

But wait, here is a buzzkill, not every MFB is in crisis. A prominent exception is MMBL. The bank is operating with zero borrowing; neither conventional nor subordinate. Further, it has a very comfortable position when it comes to advances to deposit ratio and on top of it the cost of funds is very low given the zero cost Jazzcash deposits.

A recent analysis of MMBL’s performance by PACRA states, “The Bank’s net advances clocked in at PKR 37,123mln as at End-Dec’21 (End-Dec’20: PKR 24,510mln), depicting a growth of 51 percent. The Bank’s non-performing loans increased significantly to PKR 1,247mln (End-Dec’20: PKR 68mln).”

“The infection ratio stood at 3.2 percent as at End-Dec’21 (End-Dec’20: 0.3 percent). However, the Bank’s exposure to market risk is low due to factors such as (i) nil investments in money market funds (ii) nil borrowings and (iii) a significant portion of zero cost BB deposits in the funding base. The Bank’s advances to deposit ratio (ADR) clocked in at 64 percent at End-Dec’21 (End-Dec’20: 52 percent) indicating significant growth in the loan book,” the report further added.

As per the analysis, MMBL’s growth strategy is based on caution, but what enables them to achieve this is the fact that majority of their deposits (around 70%) are from Jazz cash accounts which technically costs them nothing. This is a luxury that none of the other operators in the sector have. “The bank has never claimed to be the largest microfinance bank in the country nor are we competing on growing our loan book through unsustainable measures. Rather, our focus is to expand without compromising the quality of our lending portfolio,” explained Sardar Abubakr, the Chief Finance & Digital officer of MMBL while talking to Profit.

Yet, for the overall sector, the outlook is bleak. What further aggravates the situation is the fact that the provisioning is still not reported to its fullest extent.

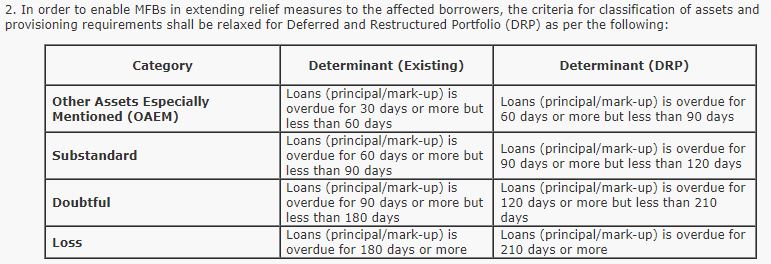

With the intent to ease the liquidity pressure on MFBs, SBP issued circular letter no 1 dated December 01, 2021, whereby criteria for classification of assets and provisioning requirements for MFBs were relaxed by providing 30 days extension for Deferred and Restructured Portfolio upto 31 March 2022.

Source: SBP

The cherry on top is the fact that the SBP is pushing for the implementation of IFRS-9 (by Jan 2024 for MFBs) which will further increase the provisioning for the microfinance sector, a serious blow to their liquidity. (Read more about it in Profit’s article: IFRS-9 likely to revamp loan provisioning)

Bail out time

Given the socio-economic importance of this sector, the government and the regulator seems keen to bail them out. For instance, the government-backed lending schemes and a shift to low risk, collateralised lending can ease out the pressure on the sector.

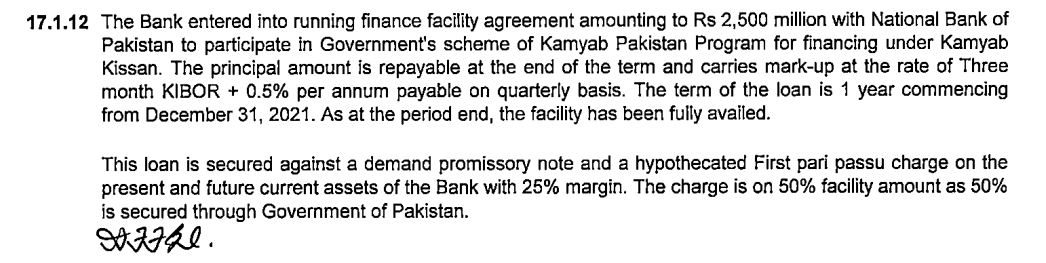

The Kamyab Pakistan Programme was one example where the government disbursed the interest-free loans with the help of commercial and microfinance banks. These loans are technically secured by the SBP, and thus reduce the liquidity risk of the sector.

Ubank recently received an interest-free Term Finance Facility of PKR 5 billion under the aforementioned scheme. NRSP bank also benefited from the scheme last year.

Source: NRSP annual financial statement 2021

Moreover, the sector is focusing towards housing finance assisted by an increased financing limit by the SBP (through the AC&MFD Circular No. 02 of 2020) as well as the Government Mark-up Subsidy Scheme (GMSS).

According to the HBL MFB’s 2021 annual report, “HBL MFB is the largest provider of Housing Finance in the Microfinance Banking Sector. HBL MFB is also one of the largest contributories from the microfinance industry in the Government Mark-up Subsidy Scheme (GMSS); as at December 31, 2021 outstanding portfolio amounted to Rs.1,149 million.”

Going back to the Khushali Bank President & CEO Review: Annual Report 2021, it said:

“The Bank plans to focus on strengthening business performance supported by enhanced credit and risk management, to improve asset quality and grow our lending share in Housing and SME finance along with mobilisation of the retail segment to generate low-ticket deposits with the introduction of new product lines.”

All these steps reduce the risk of lending for the sector, and if you recall the rule of thumb, ultimately assists the liquidity. Further, to mitigate the pressure of loan defaults the SBP through AC&MFD Circular No. 02 of 2022 extended the provisioning criteria for Microenterprise loans and Housing loans, which effectively aids the liquidity of the banks.

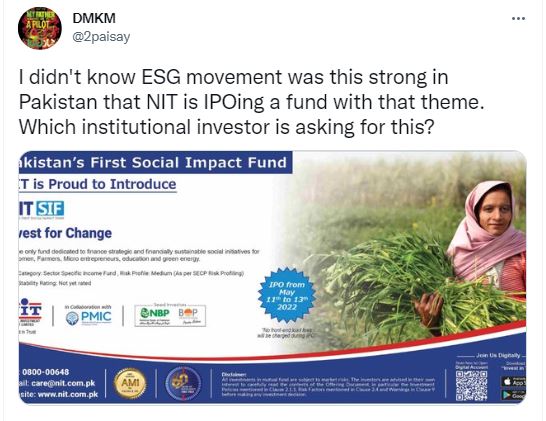

One tweet was telling. It identified a Fund of National Investment Trust which allowed upto 70% investments in the Microfinance sector categorising it as “Medium Risk”. This essentially allows another avenue for the sector to secure much-needed funding.

However, only the pandemic is not to blame for the condition of the industry. The flawed business model plays a massive role in threatening the operations of pure commercial play in the sector.

“The small loan ticket size coupled with an increased cost of operations due to accessing widespread remote areas weakens the microfinance business model. Yet, if the existing players are able to shift to a digital first approach, it could provide a spark for the turnaround of the industry,” Muhammad Havaris Arshad, a Senior Auditor of the Microfinance Sector, told Profit.

As per, COVID-19 and the Future of Microfinance: Evidence and Insights from Pakistan, an article published in Oxford Review of Economic Policy in May 2020, “Effectively coping with a volatile and unpredictable income is made easier by ready access to financial services, but the small transactions begotten by low incomes combined with fixed administrative costs make it exceedingly difficult for the market to provide those services. That has historically been the rock on which attempts to bring low-income households into the formal financial services market have crashed.”

“While it’s clear that MFIs are facing a liquidity crunch, and absent bailouts may quickly face insolvency, it is unclear what happens next. Even if bailouts are forthcoming, capital markets may be much more wary of investing in MFIs now that there is experience of how quickly normal operating procedure can turn into insolvency,” the article further added.

With how things stand currently, microfinance banks continue to find themselves in a conundrum. Efforts from the regulator to provide relief have done very little, and if serious restructuring efforts are not made or some other solution is not found, it will end with a bang.

Nice Article about microfinance and best information shared by Ahtasam Ahmad

Good detail analysis ،👍

Wow amazing sir love that analysis

Nice Article and best analysis

There was no bail out provided to the sector by the SBP. Infact the defaults are due to the policies of SBP during the pandemic which basically said that clients can choose not to pay and the MFB can recover loans after the pandemic.

No loan support, no interest support and no risk management support was given was given by the SBP to date.

So to use the word bail out is wrong and shows that the author is building a false narrative.

good article

NRSP MFB is run by a closely knit mafia. President is an Engineer by profession. Employees are not paid dues after resignations. It’s a shitty organization being fiefdom of select few

Master piece from Ahtasam Ahmad, one of the best article on current sitaution in MFBs. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks for the good information, I like it very much. Nothing is really impossible for you. your article is very good.

사설 카지노

j9korea.com

the most bad experience of microfinance is apna microfinance bank 🏦

I did best job in Nrsp bank ND the move to apna microfinance bank destroyed my career.

Allah Kareem apna bank ko tabah o barbad karay r jinhu ney Mari life kharab ki h Allah unko b tabaho barbad karay aameen 🤲

Most of MFBs are over staffed.