There is no vehicle more used, no mode-of-transport more common, and no sawari quite so quintessentially South and South-East Asian as the humble motorcycle. Two wheels, a seat, and small motor that turn those wheels through a chain. That is all you need for a motorcycle, particularly in a country like Pakistan where it is a low-cost, high-utility invention meant for everyday intra-city travel.

In the rest of the world, the story is a little different. Motorcycles are either a passion or an indulgence meant to be taken out for long road-trips and pleasure rides. After all, a motorbike is one hell of a ride on a cool summer evening or a sunny winter afternoon, but for everyday travel it is less than comfortable — particularly compared to cars and buses. In Pakistan, however, motorcycles are the most prevalent form of transportation.

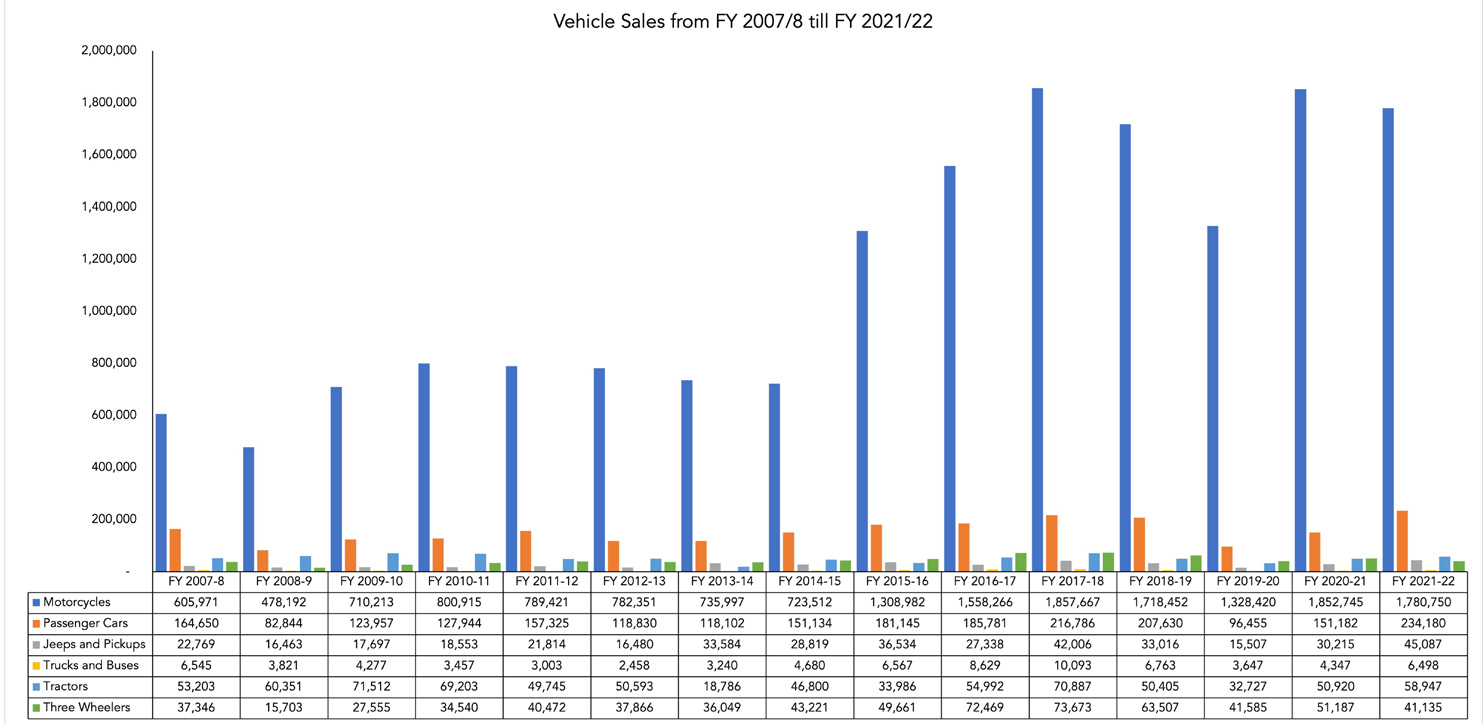

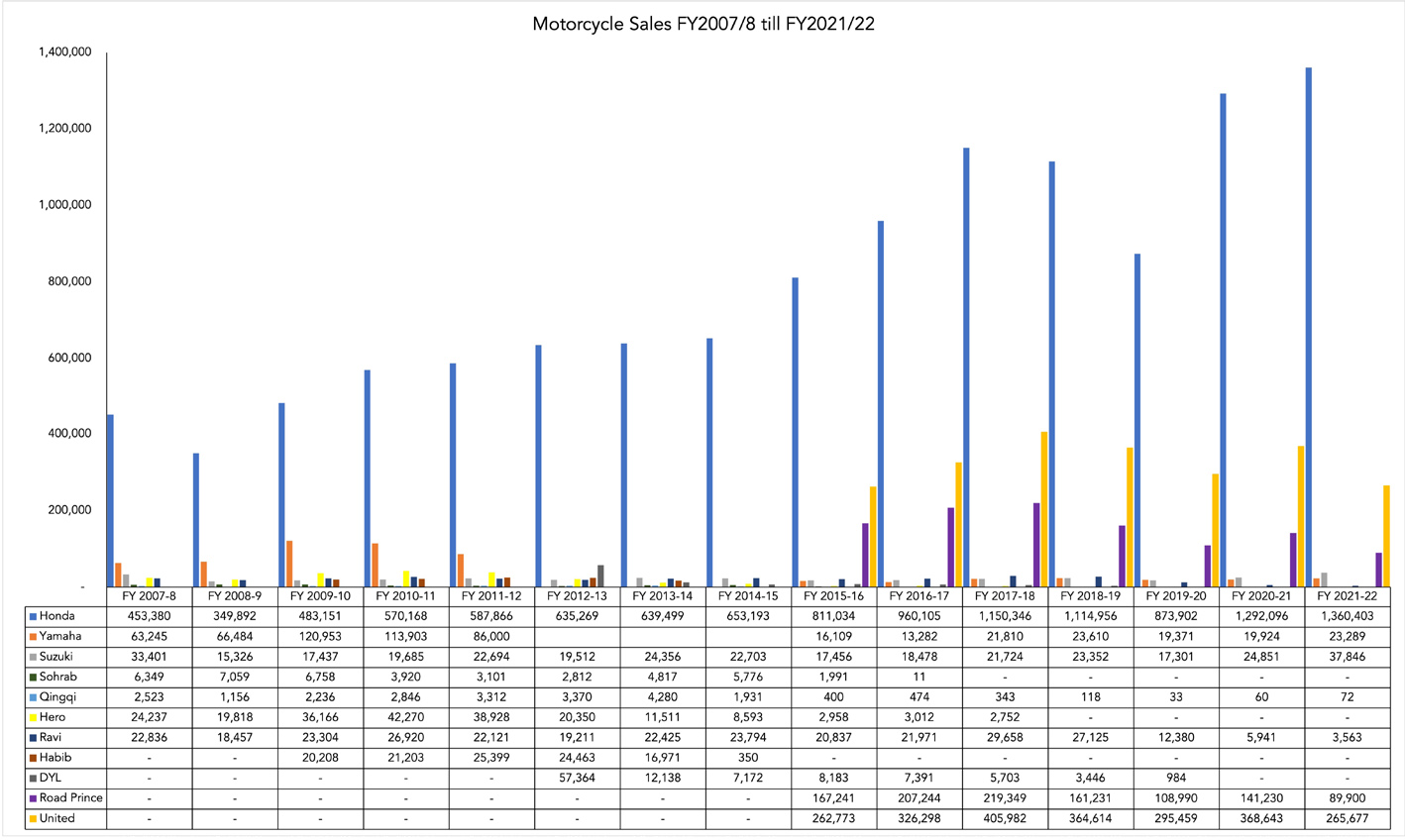

Data from the Pakistan Automotive Manufacturers Association’s (PAMA) statistics from FY 2007/8 to FY 2021/22 show that they not only dwarf every other category of vehicle, but they also sell in excess of all other vehicles combined. Multiple times over. And when you think motorcycles in Pakistan, you don’t have to look much farther than Honda of “mai te Honda hi le san” fame.

Yet the road to this point has not been a simple one. The history of motorcycles in Pakistan and how Honda came to rule them all is a long, winding road that takes us down decades of colonial and post-colonial history. At the core of the current scenario is a simple issue. Pakistan’s cities are horrendously designed and no real attention to public transport of walkability has ever been given. As life has grown faster and the population has grown, the requirement for cheap transport has burgeoned and cheap motorcycles have long been the solution. It is a story not very different from other South and East Asian countries. But to get to the bottom of it we must go back more than a hundred years. Back to a time before bikes and cars. Back to when the first petrol-engine motor car was brought to India, changing how life was lived forever.

British beginnings

It happened in 1897. A Parsi gentleman from Calcutta bought a motorcar and brought it back to India. Fascinated by this new mode of transportation, three more Parsi businessmen brought cars to India by the next year, one of them being Jamshedji Tata. That same year, the first pneumatic tyres arrived in Bombay, with Dunlop opening an office in the city. Suddenly there was no looking back.

It is hard to imagine now, but back then there were no carpeted roads the way there are now. Traffic in the Indian subcontinent had been limited to horse-drawn carriages and trams, the railways, tongas, and bicycles. It is remarkable how quickly traffic and everyday life changed and developed in the next few decades.

The motorization of transport was swift all over the world and India was not too far behind. As early as 1908 Bombay had 276 cars and 1,088 bicycles and Madras 250 and 3,146 respectively. With the introduction of motor vehicles came a major shift in life.

Bicycles moved rapidly from being used by well-to-do Britons and Indians to being, even before 1914, a means by which postmen, telegram boys, government clerks, and municipal servants conducted their business or commuted to and from work. By the 1920s the perceived ‘indignity’ of the bicycle had begun to restrict its use among both white and Indian elites. This, of course, is the first instance that we get a distinction along class-lines appearing between two-wheeler and four-wheeler vehicles.

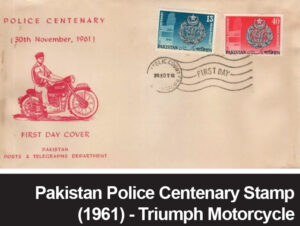

After the first world war, motorcars became much more common, even though motorbikes were still a comparatively rare sight. But even as the bicycle became a lower middle class, or even working class vehicle, an increasingly subaltern mode of transport for those who could not afford a motorbike, there was suddenly an influx of two-wheeler motorbikes coming into the subcontinent. The amount of bikes particularly saw an increase after World War Two, where they were used extensively resulting in the blossoming of an entire industry.

These motorcycles were either American or British. The most notable companies between the two included the Indian Motocycle Manufacturing Company, Harley Davidson, Triumph Motorcycles, Birmingham Small Arms (BSA), Matchless Motorcycles, and Ariel Motorcycles.

The British companies had a more solid footing in the subcontinent due to British suzerainty whilst American companies did not prioritise the subcontinent. “American bikes were brought over by merchants and priests who would sell them here if they got a good price.” Shaikh Abdul Wahid, Lead Cyclist of the British Motorcycle Club of Pakistan, told Profit.

British manufacturers had also become cash rich because of their lucrative wartime contracts leading to the British government implementing mandatory export quotas. The absence of competition, due to quite literally bombing the competition, and the surplus productive capacity led to their global hegemony.

Enter partition

At the time of partition, motorcycles were a largely accepted means of transport. And this was not a cheap means of transport. “A bike in those days cost Rs 2,600-2,700 whereas a tola of gold cost Rs 100,” explains Wahid. A tola of gold currently retails for Rs 136,582. By those standards, simply scaling the cost of the motorcycles similar to the price of gold, these British motorcycles would have cost Rs 3.5 million today — in which you could get the Suzuki Swift today.

There were two reasons for these bikes being this expensive. The first was that back then bikes were not considered a cheap mode of transportation. The second was that they were all imported. Cities like Lahore and Karachi had less motor-traffic than Bombay or Calcutta, but there was a steady demand for motorcycles. As a result, the new state started importing motorcycles. These bikes came semi-assembled, and are what we now know as “semi-knocked down” (SKD) units, which meant the two-wheelers came partially assembled and some of the fitting and assembling would be done in Pakistan.

“They were brought in wooden crates and were then assembled here,” said Wahid. As a result, a small industry began to emerge surrounding the assembly of these SKD unit motorcycles. Polad, Universal, and Lotia were local companies that set-up shop in Karachi to assemble the British motorcycles by engaging in partnerships with their British counterparts. Universal began assembling Triumph and BSA motorcycles, Polad assembled Matchless motorcycles, and Lotia assembled Ariel motorcycles. These companies then built up their own networks of mechanics whom they taught how to assemble the motorcycles, and subsequently incorporated them as dealers to sell the motorcycles.

Now the thing with SKDs is that it is a good trade-off for when you want to manufacture something locally without possessing the requisite industrial base. However, it is a temporary solution at best. Ideally, you want to be importing any vehicle as a completely-knocked-down (CKD) unit and then assemble the whole thing yourself. This would give you the lowest cost of production in the long-run but also requires immediate capital injection to set-up assembly lines capable of efficiently putting together CKD units.

So here was the situation. If you wanted to convert your industry from SKD to CKD, you had to have more volume in demand. To do that, the bikes had to be cheaper. And that would have meant producing lighter quality more practical motorcycles designed specifically to be cost-effective. For decades after partition, the SKD model continued as was. Some tried to import bikes from Japan and China as well, but British and American motorcycle manufacturers like Triumph continued to dominate the streets of Lahore and Karachi. But as the population grew and cities began to sprawl, the demand for cheap vehicles grew. And that is where Honda comes in.

The big-three (wheels): Vespa

No, we do not mean Toyota, Honda, and Suzuki. Because before these three companies entered the market and took over there was another important big-three that made an impact on Pakistan’s motor-history: the three-wheeler Vespa.

Perception is an amazing tool. Up until the 1960s, motorcycles were considered an upwardly mobile means of transportation. They were driven by government officers, bankers, and other professionals and considered a sign of doing well in life. That is why, perhaps, few could have imagined that cheap versions could be successful on a larger scale.

A local company called Khawaja Autos brought the Italian scooter brand Vespa to Pakistan. Cheap, slow, and decidedly un-sexy, the Vespa was the every-man vehicle. The sheer sales volume achieved by Khawaja Autos through this move proved to be a game changer. One of the unexpected results was that mobility suddenly increased, and it became apparent that there was room in the market for more cheap transport accommodation. The problem became, however, that Khawaja Autos doubled down on three-wheeler scooters. The environment was all but ripe for someone to take advantage of. And that is when Honda came in and began the Japanese domination of Pakistan’s automobile industry.

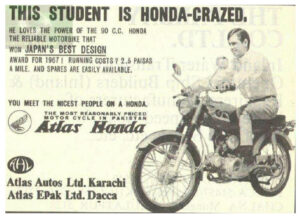

Yusuf Sherazi, the chairman of the Atlas Group, realised this. He became the first Pakistani to gain licensing for the manufacture of motorcycles in partnership with Honda Motors of Japan, along with Syed Wajid Ali, the brother of Syed Babar Ali. Together, the two families set up the motorcycle industry in Pakistan, and the Atlas Group saw a meteoric rise. Honda itself was formed in 1948, but by 1955 had become the leading Japanese manufacturer of motorcycles. So, in 1962, when Atlas Autos signed an agreement with Honda, the Japanese company was only 15 years old. Pakistan at the time was the fifth largest country in the world behind China, India, the Soviet Union and the United States. Honda came to India in 1995, and brought motorcycles there in 1999. In Pakistan, Honda brought motorcycles in 1962, and cars in 1992, entirely due to the efforts of Shirazi. The first two factories that Yusuf Shirazi set up were in Lahore and Dhaka. The project was an instant success, and Honda was followed into the market by Yamaha, which commenced operations in 1968 with an assembly plant in Balochistan. However, they could not replicate the same success as Honda and had two failed local ventures.

Then, in 1971, disaster struck on a national level. The independence of Bangladesh meant that half the country was now another nation, but it also meant that all the private industry set up in erstwhile East Pakistan was now no longer available to them, including one of the motorbike plants. However, there was also a silver-lining. By this point, Honda motorcycles had become common-place in Pakistan. The independence of Bangladesh meant significantly reduced purchasing power and the overall market for high-end British motorcycles. Globally, British motorcycle manufacturers had lost significant ground to their Japanese counterparts. The Japanese initially built mostly small motorcycles with an engine capacity of less than 250cc, but had gradually moved ‘up’ the market with larger and larger motorcycles. In contrast, by 1975 the British industry produced nothing smaller than machines in the 500cc engine displacement class, with the majority of production in the 750cc and 850cc classes, and had nowhere left to retreat.

Smaller bikes, bigger money: How the market shaped up

With British motorcycles down in the dumps, Honda once again saw a spike in demand. Yamaha also launched again in 1974 which proved to be more successful than their last couple of efforts. In 1976, the exact results of this shift became apparent. In that same year, Honda Atlas launched the now iconic CD-70, and CG-125. Yamaha launched their YBR-100 Royale, and Sindh Engineering Limited introduced Suzuki to the Pakistani motorcycle market. Suddenly, there was an influx of cheap and easily available motorcycles in Pakistan and the industry saw healthy competition too. In fact, the main event of 1976 was not the now classic CD-70, but the YBR-100, which propelled Yamaha to immediate stardom whereas Honda would only catch-up later.

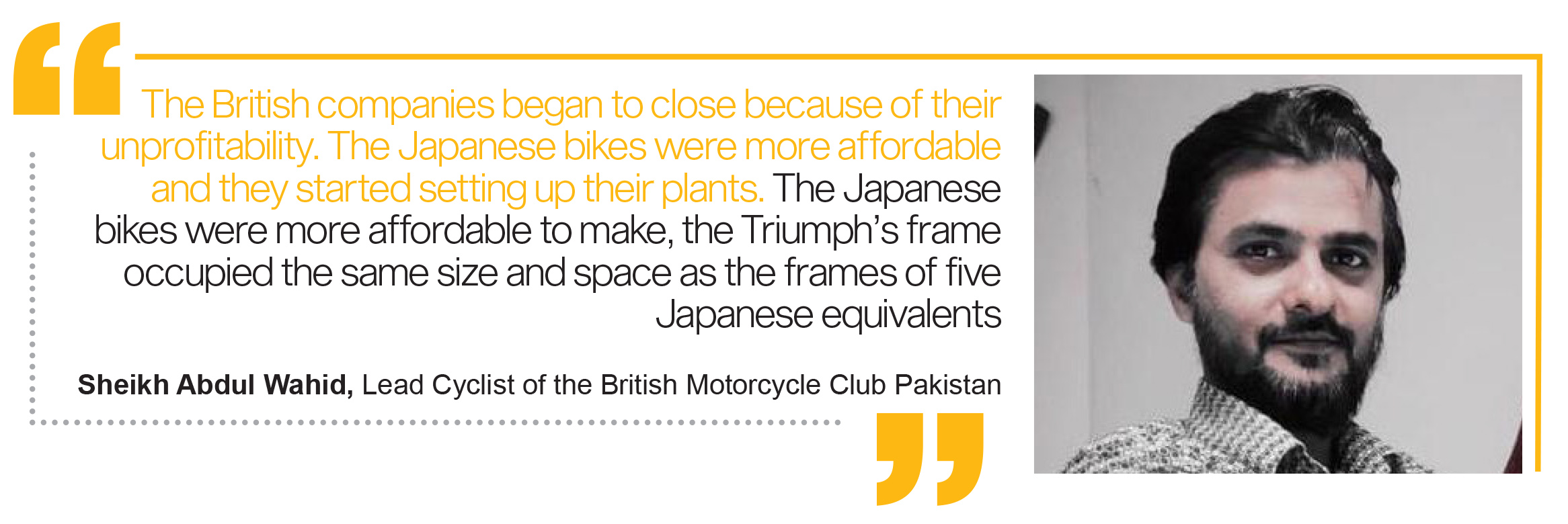

“The British companies were lost. They began to close because of their unprofitability. The Japanese bikes were more affordable and they started setting up their plants.” said Wahid. “The Japanese bikes were more affordable to make, the Triumph’s frame occupied the same size and space as the frames of five Japanese equivalents,” Wahid explains to Profit.

Localisation was also a problem. Remember, how we said SKDs were a short-term fix? Well, the British companies just continued to utilise the jugar on the assumption that the economy would remain stable and the good times would continue. “They never considered localisation. Royal Enfield was smart, they set up a plant in India and have continued producing bikes there. Ours completely shutdown. In the end their parts were still available till 1988-89, after which the assemblers auctioned off everything and closed shop.” said Wahid.

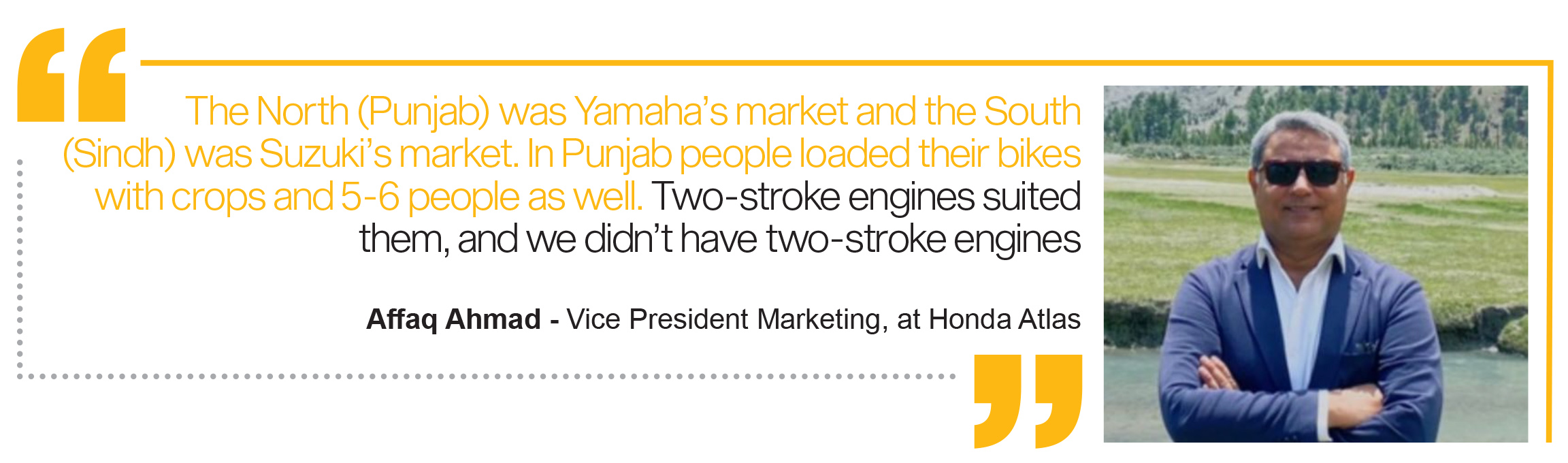

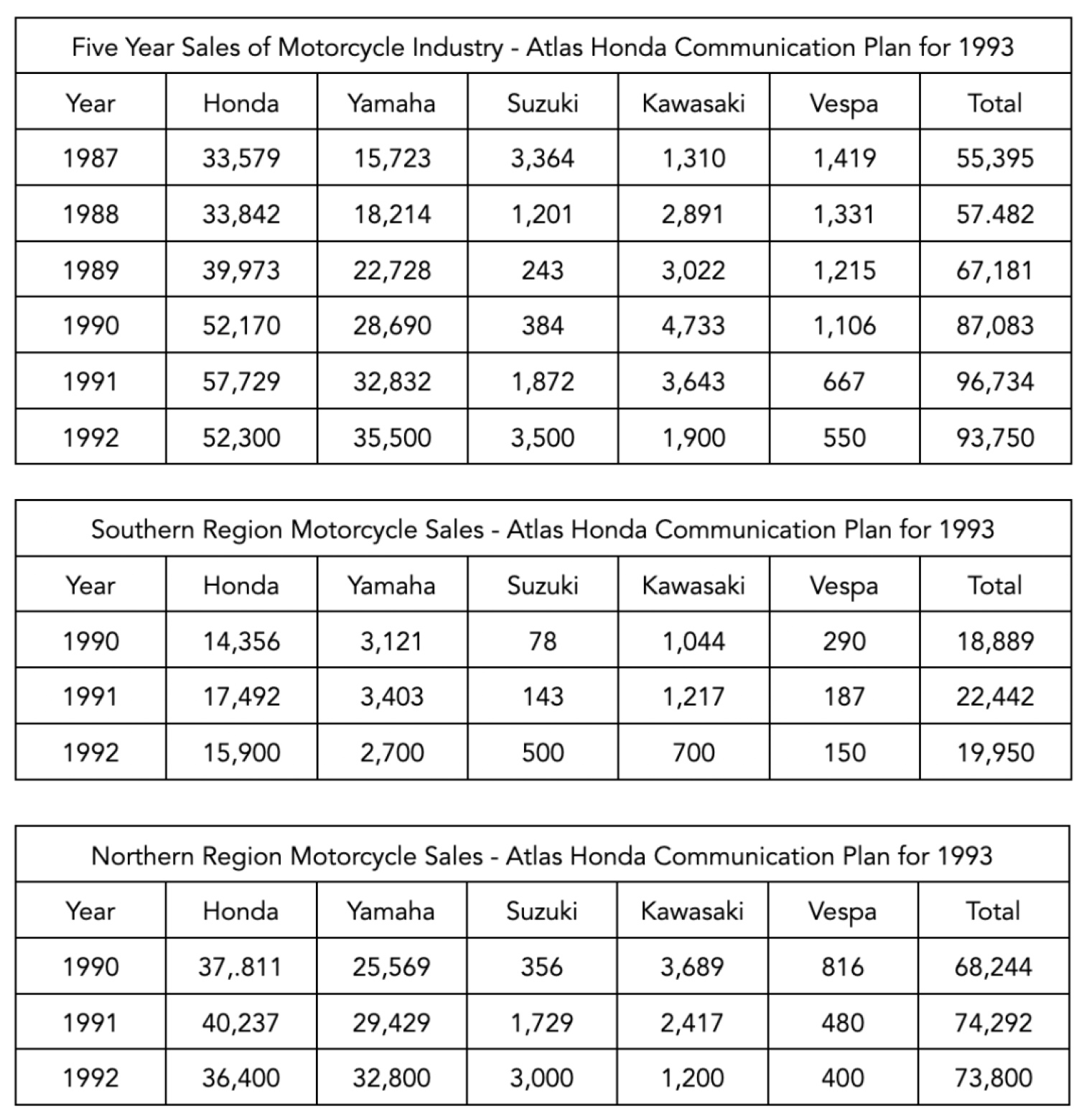

Localisation, scale, and cost would all be words that would come to categorise the industry for decades to come. And it would be off those concepts that Yamaha would be able to dominate the market for the years to come. Even though Honda had a first-mover advantage, losing their factory in Dhaka proved to be a significant blow. On top of this, Yamaha used a combination of clever tactics and good marketing to become King of the Ring. “The North (Punjab) was Yamaha’s market and the South (Sindh) was Suzuki’s market.” said, Afaq Ahmad – Vice President Marketing, at Honda Atlas. “There was a time when people said mai Suzuki lena aya hun like it was a fridge. It was like Xerox with printing. And in the North, you’d have people say Yamaha gaddi kadani ha.”

“Suzuki outsold Honda in Punjab. Customers would go to Honda showrooms and demand to buy a Suzuki because the bikes were so similar and Suzuki had such a strong footing” Muhammad Sabir Shaikh, Chairman of the Association of Pakistan Motorcycle Assemblers (APMA), told Profit.

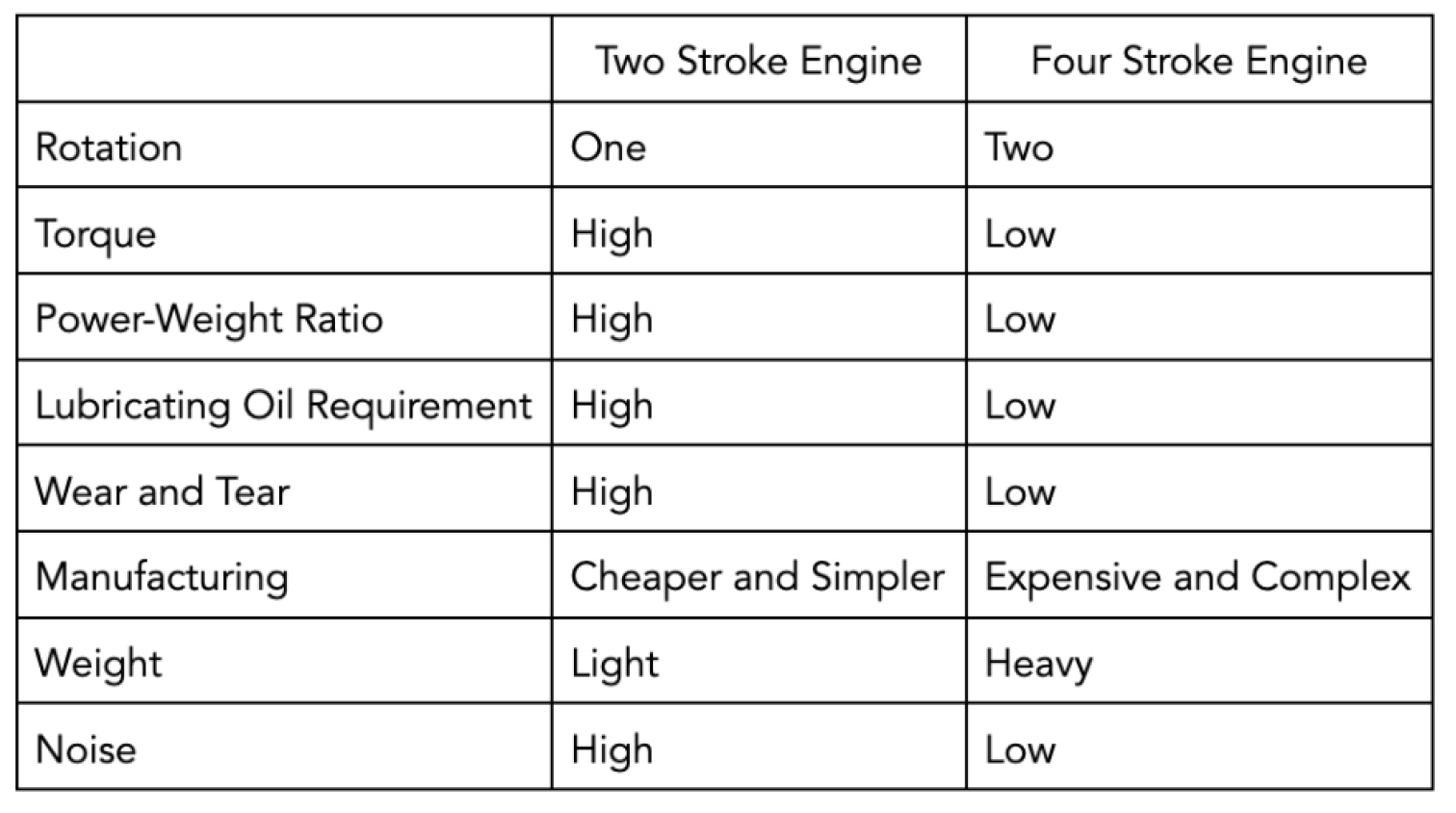

Honda’s misery was largely a result of their choice of engines for their motorcycles. “Our bikes were not two-stroke. Two stroke engines produced more torque and the acceleration was immediate. This fascinated people” continues Honda’s head of marketing Affaq Ahmad. “The two-stroke engine also enabled Yamaha’s domination of rural Punjab. In Punjab people would even transport their crops on bikes and sometimes 5-6 people would be on one bike. For these purposes, two-stroke engines were ideal.”

Two stroke engines apart from being more powerful in the specific aforementioned manner, were also simpler mechanically which provided Yamaha and Suzuki with an intrinsic advantage. These engines have fewer moving parts, and are thus cheaper and easier to service which reduced the cost of ownership for buyers whilst also making them the darling of mechanics. Is this last bit important? Well, yes. “Every product has an influencer and the influencers for motorcycles are the mechanics. They are the opinion makers.” Ahmad told Profit. “Suzuki and Yamaha’s product was easy to disassemble, assemble, and fix. This allowed them to quickly build a network of mechanics.”

The legend of Kawasaki

By the 1980s, three Japanese companies had a hold on the motorcycle industry. At this same time, Honda and Suzuki were both also trying to expand into cars with the introduction of Toyota to Pakistan. But in the field of bikes, the Big Three were Yamaha, Suzuki, and then Honda — all in that order. Until that trinity became a quartet.

The introduction of Saif Nadeem Kawasaki Motors Limited in 1982 changed the game. Back in the early days before Vespa and Honda, motorcycles were cool. They had an overreaching sex appeal. After they became cheaply available and the Japanese iterations took over the British ones, things changed a little. For sure, bikes were still designed to be good-looking but with the cheaper ones you could only do so much. And most people were buying the smaller ones such as Yamaha’s 100cc. Kawasaki changed this entire scenario by introducing cheaper bikes made to look longer, sleeker, more American (very much like the motorbikes that the famous detective novel series the ‘Hardy Boys’ had made popular).

Kawasaki became the bad-boy motorbike. They had established an assembling plant in 1977 but with the introduction of this new venture, it doubled down on the Pakistani market. Kawasaki jumped on the two-stroke bandwagon. It was a no brainer for the time. The dealer network existed and that’s what the customer wanted. To differentiate themselves from everyone, Kawasaki went straight for the upper end of the price spectrum.

“The Kawasaki 70 was very popular. It’s still a vintage bike here.” said Ahmad. “It’s GTO 125 was matchless.” Kawasaki was such a phenomena and so loved by its customers for its performance that its bikes were dubbed widow makers. The Japanese quartet could be broken down into the two-stroke trinity of Yamaha, Kawasaki, and Suzuzki, and then Honda separately with its four-stroke alternative. Honda did try to enter the two-stroke market by introducing its two-stroke MB-100 in 1980 and the H-100S in 1982. However, both models were largely unsuccessful.

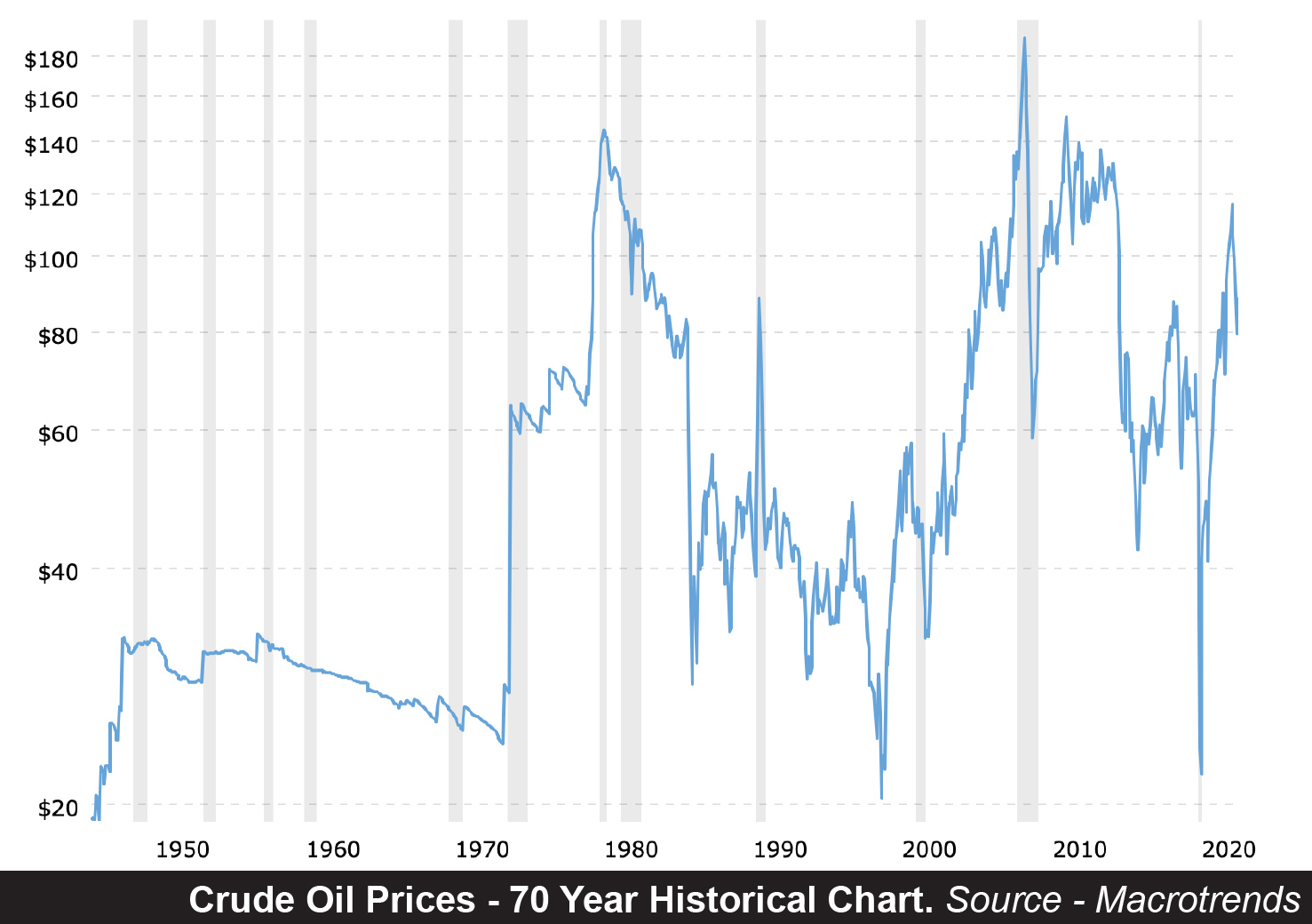

Honda’s limited initial success and the imperious run by the quartet was not just a Pakistani phenomenon though. This 1960’s to the 1980’s is what many argue was the golden age of two stroke motorcycles with the aforementioned trinity dominating globally. Until 1984 happened. But then came the crash. In 1984, the sale of two-stroke cars and motorcycles was banned in the USA. The ban was implemented to tighten emissions regulations on vehicles. Two-strokes couldn’t be modified to reduce their emissions to an acceptable standard, therefore they were no longer road legal. This was a major reset for motorcycle manufacturers which prompted the shift to four-stroke motorcycles lest they continue to stay frozen out of the, then, largest motorcycle market.

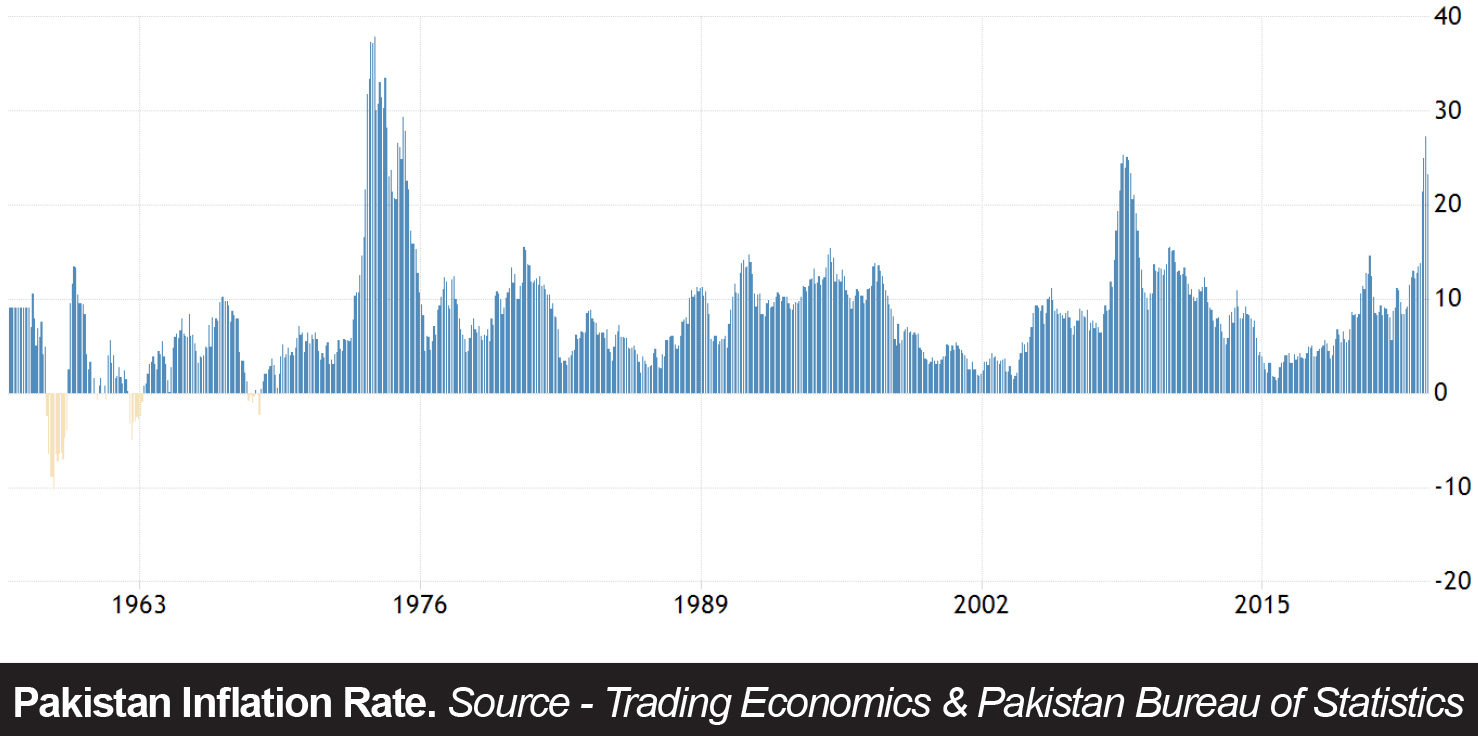

Now, this did not translate directly to Pakistan. In fact, to this day there is no regulation in the country against two-stroke motorcycles. However, it was more convenient for the Japanese parent companies to have their domestic portfolio running in Pakistan as well, which saw an end to the two-stroke phenomenon. On top of this, two-stroke bikes also ate more petrol and were more expensive to maintain.

Honda’s era

The four-stroke engine was considered the better alternative, both in Pakistan and globally. And this is when Honda lucked out. It was cognisant of how the industry was on the precipice of a shift in the 1990s, and it sought to capitalise on the opportunity by making a few smart marketing decisions. In 1992, Honda released what Ahmad referred to as the “Big CD-70”. This was Honda borrowing from Yamaha’s and Suzuki’s playbook whereby they abandoned their smaller frame for a more domineering one.

“Our CD-70 looked very small in comparison to the competition, which did not appeal in particular to customers in Punjab. Yamaha’s bigger fuel tanks made them look bigger as well” told Ahmed. “To survive in Punjab, we decided to enlarge the frame. We increased the wheel-base, the fuel tank, and the seats so that we could reposition ourselves against Yamaha” continued Ahmed. It was also around this time that Honda sought to capitalise on the rising fuel costs and highlight the four-stroke engines fuel efficiency relative to its two-stroke counterparts with their “aik bhi bohat hai” ad set. At a time of increasing fuel prices again, this just worked.

The onset of the 1990s was perhaps the first time that the term ‘and the rest is history’ could have been used for Pakistan’s most iconic motorcycle. This transition from the two-stroke to four-stroke is also what laid the groundwork for the shift from the Big 3 to the Big 1 in the motorcycle industry.

There are no publicly available sales figures for this time period, however, Profit was able to acquire Atlas Honda’s Communication Plan for 1993 to identify the sales throughout between 1987-1992. Looking at the figures, Honda’s dominance is evident with the company having a 56% national market share at its lowest. The numbers also corroborate Ahmad’s statements whereby despite Honda’s imperious figures, Yamaha retained brand equity in Punjab unlike its other former two-stroke contemporaries.

The most notable change was Suzuki’s capitulation to Honda in the Southern region where it lost key markets such as Hyderabad and Karachi. Suzuki’s losses were so concerning that In 1991, Suzuki Corporation of Japan started taking a more active interest in Suzuki operations in Pakistan. In late 1991, there was a major management change in Suzuki of Pakistan whereby Mr Danishmand, previously the CEO of Atlas Honda, was made head of Suzuki.

Not only would the aforementioned trinity have to play on Honda’s playing field, but they would also run into their own struggles, and in particular rely on Honda’s mechanics. Setting four-stroke as the standard and its mechanics as the default, Honda had made the rules of the game very clear. However, whilst everyone was fixated on how the two-stroke trinity would transition, the groundwork had been laid for newer entrants who want to leverage this established infrastructure to launch themselves.

The Chinese make a splash

If there is one thing that this entire long-winding history of motorcycles in Pakistan teaches us, it is that the most important part of getting a motorcycle business up and running has been localisation. Failing to localise is why the British motorcycle industry collapsed abroad. It is also why others failed, and how in recent years a number of Chinese manufacturers have been able to enter the market.

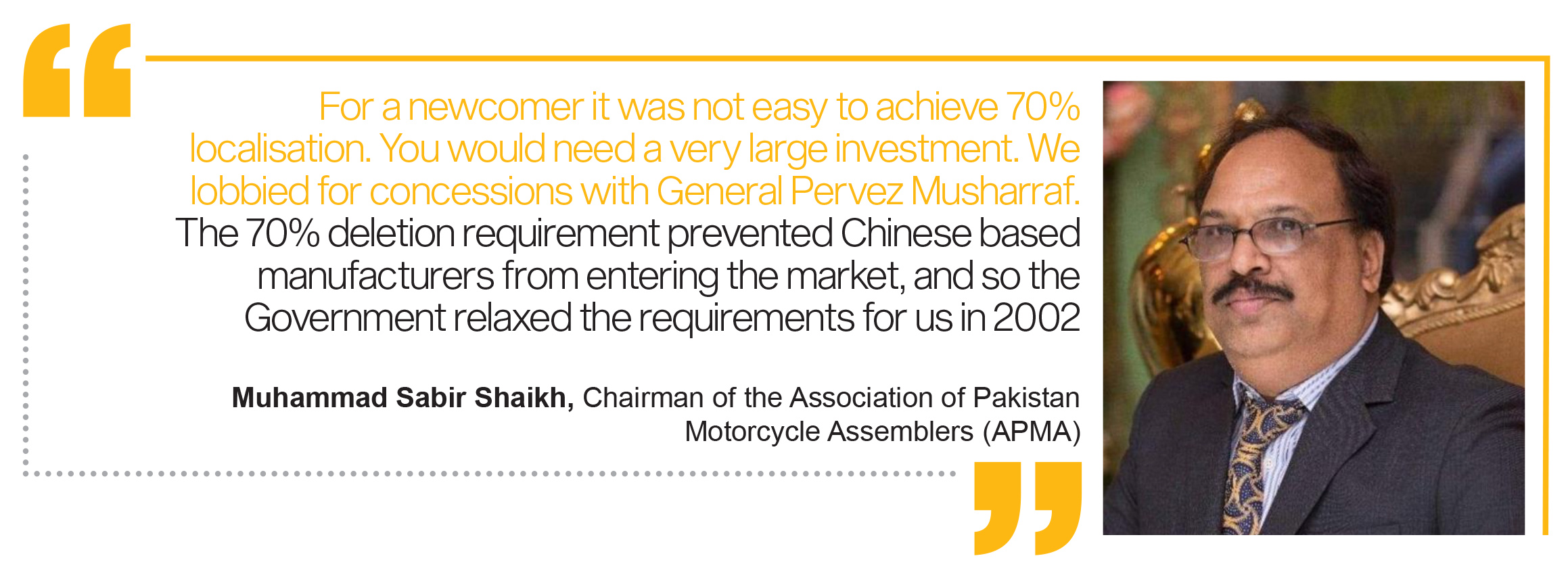

“For a newcomer it was not easy to achieve 70% localisation. You would need a very large investment” said Shaikh, Chairman of the Association of Pakistan Motorcycle Assemblers. However, 1994 proved to provide an opportunity that was too good for the taking. Why do we say this? Well, this was the last year of production for Kawasaki. “Kawasaki had financial issues and it failed to meet the localisation requirements.”

Kawasaki’s woes were common knowledge and subsequently Sohrab Cycles rose to the occasion with its JS70.“It was the first Chinese motorcycle.” Ahmad told Profit. “Sohrab made a good machine and undertook localisation. It’s bicycle background helped it with electroplating. Their rims are still better than most of the market to this day.” continued Ahmad. Sohrab’s entry and Kawasaki’s exit prompted other companies to jump the gun as well, most notably Plum Qingqi Motors in 1995 and United Autos in 1999. These companies were then followed by Hero and Pak Hero in 2000.

Chinese motorcycles are ubiquitous now, but in reality they came through the continuous efforts of multiple manufacturers to establish themselves through trial and error. Breaking into the motorcycle industry was initially a very painful task. The Government initiated a localisation program in 1987. In 1995, it launched the Product Specific Deletion Programme (PSDP) to nurture the industry in its infancy and support its growth by requiring OEMs to achieve local content levels of at least 70%.

However, many in the automotive market began to realise that there was potential for additional sales volume particularly due to the increased motorcycle production capacity across the border in China. “You could find Chinese replicas of the CD-70 for $250 whereas it was sold for $1,000 here.” And where there’s a will, there’s a way. The breakthrough for the Chinese manufacturers came first in 2002, and then in 2004.

“We lobbied for concessions with General Pervez Musharraf. The 70% deletion requirement prevented Chinese based manufacturers from entering the market, and so the Government relaxed the requirements for us in 2002” said Shaikh. Shaikh’s comments are in reference to the reduction in import duties by, then, Finance Minister Shaukat Aziz in 2002. This led to seven new companies entering the market. These new Chinese entrants setup shop in Hyderabad and Karachi. Most notable of them, that still commands a sizable market share today, would be Super Star. The real breakthrough, however, was in 2004. To put it into context, if 2002 was a crack in the wall, then 2004 was the wall coming down entirely. So, what happened? Pakistan scrapped its localisation program entirely. Albeit, not of its own free will.

Local players reached out to prospective partners in China and began importing vehicles in droves. How many companies sought to establish themselves as players in the motorcycle space? “A lot of brands came. I think there were more than 100 applicants” Muhammad Salman, Director of Sales and Marketing at Road Prince, told Profit. Shaikh puts the exact number of applicants at 125. However, there is no official count as to how many applicants proliferated the market throughout the 2000s. The floodgates were open and it was essentially the wild west.

For the sake of brevity, Profit will identify the major players that entered the fray and continue to operate at a reasonable scale. These firms can be divided into the Hyderabad and Lahore based ones as a secondary filter. The former included Unique in 2004, Super Power in 2004, and Hi-Speed in 2004. The latter included Road Prince in 2004, and Ravi in 2007. From 2002-7, sales increased year-on-year peaking at 195,688 in 2007. What led to the ascent of these companies? Deferred payments. Lots of them.

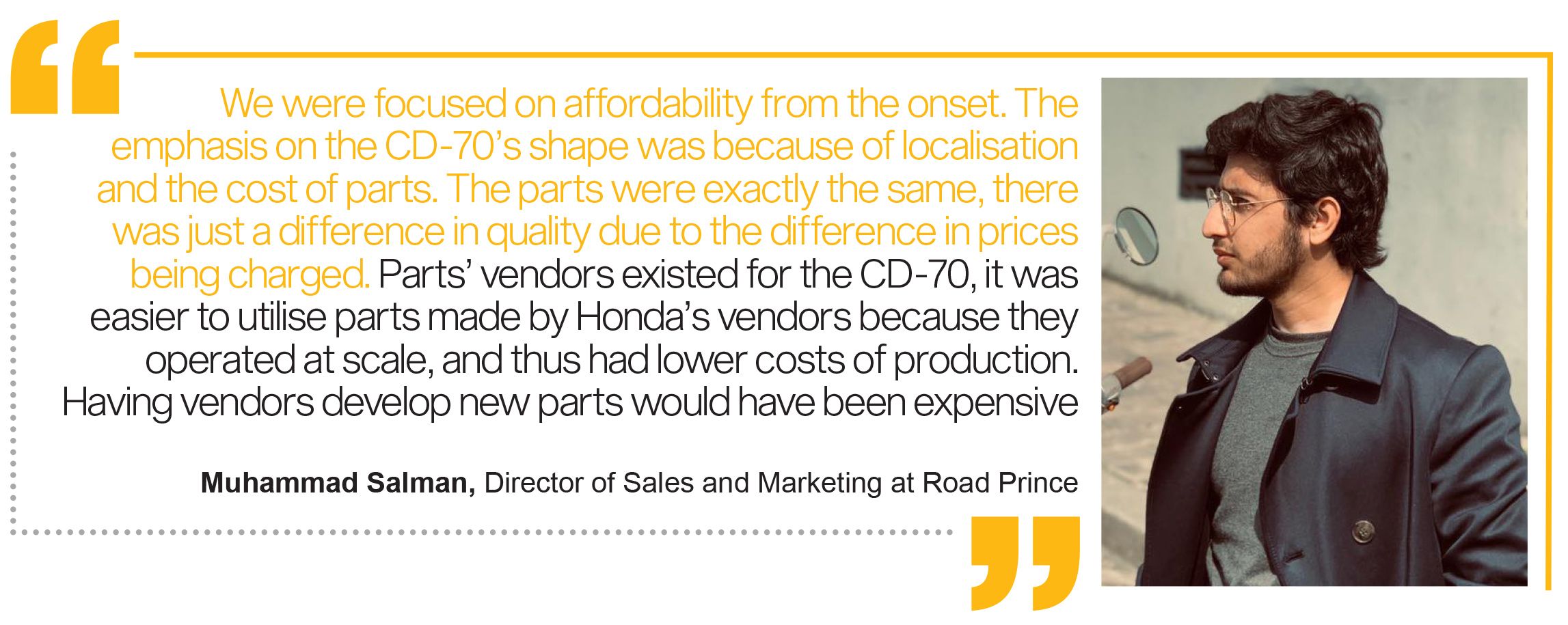

“Honda originally used to lease its motorcycles to its dealers so we, along with our contemporaries adopted the measure as well. We gave credit terms of 8-9 months. The deferred payments gave us a boost in sales” said Salman. Moreover, Chinese brands focused on affordability. Doubling down on the CD-70 provided them the opportunity to initiate a race to the bottom in terms of prices due to the infrastructure of dealers and vendors that the Japanese, Honda in particular, had established.

“We were focused on affordability from the onset. The emphasis on the CD-70’s shape was because of localisation and the cost of parts. The parts were exactly the same, there was just a difference in quality due to the difference in prices being charged. Parts’ vendors existed for the CD-70, it was easier to utilise parts made by Honda’s vendors because they operated at scale, and thus had lower costs of production. Having vendors develop new parts would have been expensive.” continued Salman.

So how did the Japanese incumbents respond? Well, it was in 2004 that Honda introduced its iconic “Mein te honda ee lay saan” as a response. While the Japanese bikes had originally entered as the cheaper option to the British bikes, they now presented themselves as the quality, legacy, product. Suzuki consolidated its presence in Pakistan by incorporating its motorcycle division (Suzuki Motorcycle Pakistan Limited) into its main car business (Pak Suzuki Motor Company) in January 2007. Finally, Yamaha suffered from a divorce between the Japanese parent company and its local partner in Pakistan in 2008. The local partner, the Dawood Group, retained the infrastructure and production facilities, and relaunched Yamaha as DYL. A spin on the original Dawood Yamaha Limited (DYL) name.In hindsight, it’s not hard to tell which of the three made the better decision.

The state of the industry

Moving beyond the late 2000s till now, there are perhaps just three major highlights. Honda’s absolute domination of the industry, the Chinese entrants entrench themselves, Yamaha returns to the market and repositions itself in the Pakistani market alongside Suzuki.

Let’s start with Honda’s domination. What do we mean by that? Put simply, there was a Big 3, and there was the Chinese, but at the end of the day, there’s really just one company in the sector. Profit looked at sales figures provided by PAMA from FY 2007/8 till FY 2021/22. Honda was the single largest player every year. Every year, it was also greater than the sum of all other players combined. On average, it produced 455,911 more motorcycles than all its competitors combined. This reached a peak in FY 2021/22 where it produced 940,056 more units than all other competitors combined whilst at its lowest in FY 2008/9, it still produced 221,592 more units.

The remaining six entrants have solidified themselves in the Pakistani market as the last ones standing. Not only have they been able to create their own brands and personas, but just the sheer amount of time that they have spent operating in the industry have reduced the moral hazard that many customers associated previously with the Chinese market due to how permeable it was. The Karachi and Hyderabad based companies are not members of PAMA, and therefore their sales figures are not available. However, based on Profit’s interactions with the aforementioned sources, alongside others, we have a solid idea as to where they stand. The Sindh centred competitors would roughly lay between Road Prince and Ravi in terms of sales volume. As to the particular hierarchy amongst themselves, well, Profit was unable to ascertain that due to the negligible difference in volume between all of them.

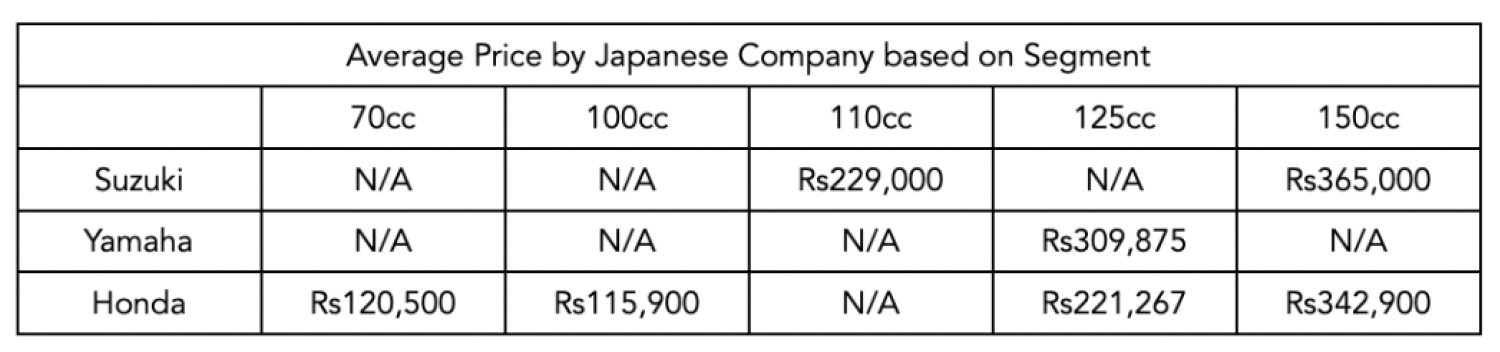

Finally, the relationship between Honda and its Japanese counterparts. Yamaha Motors had split with the Dawood Group due to Dawood’s reluctance to move beyond the affordable segments. Yamaha, on the other hand, realised that a race towards the bottom in terms of pricing may not be the most profitable strategy for them to employ. Thus, when they relaunched the brand in 2015, the aim was to cater to a new target market. Similarly, Suzuki sought fit to compete in the more premium segment. This was largely due to Suzuki’s car segment being the company’s bread and butter. Suzuki could therefore afford to compete on the more premium segment on account of the scarce competition there and because it largely did think of the segment as ancillary to its core car operations.

So how different were Yamaha and Suzuki in terms of market positioning this time around? Well, they completely extricated themselves from the 70cc segment. Once, the main battleground for all three was now served solely by Honda. Yamaha and Suzuki do not compete with each other in any segment but do compete with Honda. The former competes with Honda in the 125cc segment, whereas the latter competes with Honda in the 150cc. In both segments Yamaha and Suzuki offering is appreciably more expensive than Honda’s.

Now that we’re all caught up now, the lurking question that might pop in anyone’s, anyone at least into motorcycles or who read the introduction to the CD-70 and CG-125, mind at this point is why is that still the dominant motorcycle in Pakistan? By that we do not mean just Honda’s offering but also as to why the design is the darling of the Chinese manufactures?

The simple answer is cost and scale. It’s cheap to make, which leads to customers buying it, which in turn allows companies to make it en-masse and incur lower per unit costs. Simple economies of scales really. Are we likely to have more modern and better motorcycles become as ubiquitous as the CD-70 and CG-125? Maybe.

It’s not impossible for either Honda or the Chinese to do this. It’s just very hard. What do we mean? Let’s start with the Chinese reason for sticking with the tried and trusted bike designs. “We’re a local brand, not an international one. The Japanese are backed by their foreign parents whereas we have had to navigate the market on our own. We’ve only begun exploring the premium market recently as our footfall has improved. If we were to partner with a foreign company for the premium segment then we would be able to easily capture market share as well.” Salman told Profit. However, Salman didn’t tell Profit as to why Road Prince hasn’t done exactly that. The answer to that Profit found with Honda.

“We have a very large lineup but only two of our models are successful. Companies cannot bring new models because they are stillborn because of how expensive they become due to the duties. The government will not only need to align localisation to protect existing investment but also provide space to import new parts not found in Pakistan needed for the newer models.” Ahmad told Profit. What does he mean here? The aforementioned three SROs that are attached to the TBS mechanism.

As a reminder as to what they are. They are the duties that are levied on imported parts. Their aim is to discourage imported inputs and encourage companies either using local inputs or making the requisite inputs here themselves. “Localisation cannot happen without scale. The SROs need to be revised for higher engine displacement models whereby grace periods are given to allow companies to build the volume needed to localise the parts.”

We’ll likely have to add a new section entirely to this piece in case the Government does act on the recommendations. Until then, we can just add FY 2022/23’s data to the graph as the trend looks stable going forward. Unless of course, we have a new country emerge as a juggernaut with its motorcycle industrial complex to dislodge the Chinese.

Federal Government must immediately announce new Policy for made in Pakistan Scooties, Electric Scooties, Less than 250cc Engine based Motorcycle in Pakistan to Save Foreign exchange reserves of the Country.

Meanwhile, Honda has released a new sticker for the Honda CG 125 Self 2023 model. Except for the new adhesive sticker, the 2017 motorcycle has no additional features over the previous year’s model. It is worth noting that the overall design of the CG 125 Self differs slightly from the standard model.

very nice article story about motor cycle

very interesting blog, I really appreciate the author

A very insightful article to highlight a much valid point, however I would have appreciated if some recommendations for the solution were also presented here.

사설 카지노

j9korea.com