Has the aftermath of the Aurat March this year been a little bit less vociferous in its hate? Or have we just got so used to being demonised that we’re not feeling the heat as much? Amongst the myriad conversations that took place at the marches but most especially in the days following them, one particular plaint has stood out.

It is the barrier that many women still face in Pakistan: Access to financial services.

Pakistan is part of the seven-nation group that has more than 50% unbanked population. So there are no surprises there that women’s ownership of bank accounts lies abysmally low at 7%.

It is commonplace to have joint bank accounts with husbands as co-owners. According to a recent report discussed at the launch of Standard Chartered’s women-specific banking titled “SC Sahar Women’s Account,” in February, only 14 million bank accounts are owned by women, of which one in six are operated by women, the rest are joint accounts with men.

These stats tell a story. Women essentially do not have agency over their own money. In conversation with Profit, a young working woman who wishes not to be named, said that after she got married the couple decided to open a joint bank account for savings. But “Now I can’t even take out my money to spend on my parents’ needs and luxuries without giving him a justification. I don’t ask him where he spends his money but because he gets to know every time I take out money it becomes a matter of discussion,” she said.

“When I got my first job in 2021, I went to Bank Alfalah to open my bank account,” says Memoonah Asad, a young woman in her 20s. On the first day, no banking agent paid heed. Maybe I looked too young, or maybe it was just because I was a woman. I kept telling them that I’m running out of time so eventually, I left. The next day when I visited they kept asking me for a ‘valid’ source of income even though I did show them proof of my employment. On the third visit, I took my father along and once he showed them his proof of income only then they started the process.”

Asad points out two major contentions: Relatability and documentation. In 2021, SBP noted that only 13% of the banking staff and 1% of the branchless banking staff are women. Therefore, like Asad, a lot of women feel intimidated to visit the bank as they fear they won’t be taken seriously. So they can never really be financially literate enough to understand which documents are needed.

Unbanked women

In the last few years, the gender gap in financial services has widened significantly. This is mostly because the population is slowly becoming part of banking and financial services, but it comprises mostly men. “The majority of unbanked adults continue to be women even in economies that have successfully increased account ownership and have a small share of unbanked adults. In Türkiye, for example, about a quarter of adults are unbanked, and yet 71% of those unbanked adults are women. Brazil, China, Kenya, Russia, and Thailand also have relatively high rates of account ownership, compared with their developing economy peers, and yet a majority of those who are still unbanked are women. Things are not much different in economies in which less than half the population is banked. For example, in Egypt, Guinea, and Pakistan women make up more than half of the unbanked population,” says World Bank’s Findex Report, 2021.

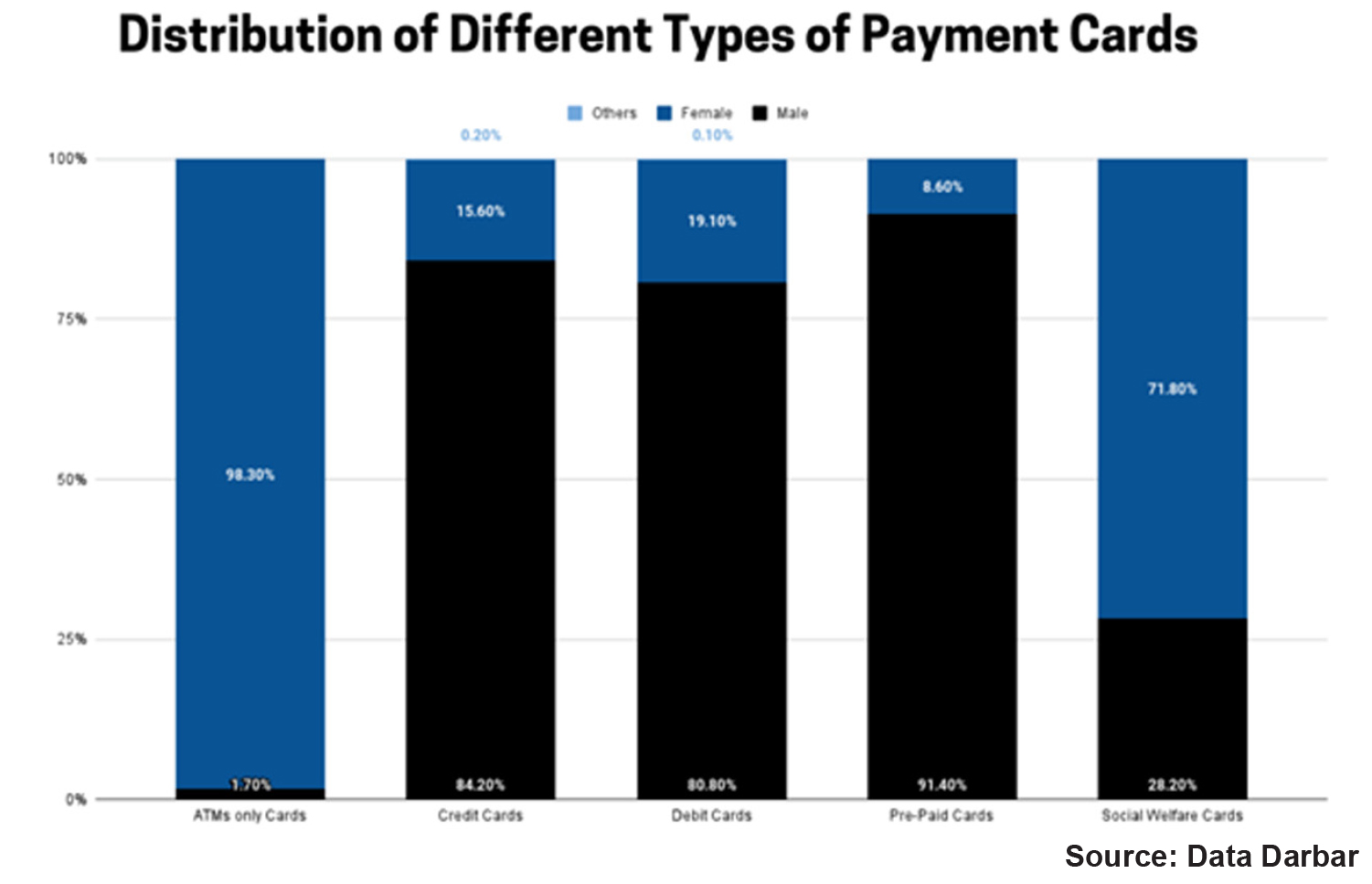

Below is the breakdown of women’s participation in banking services in Pakistan compared to men:

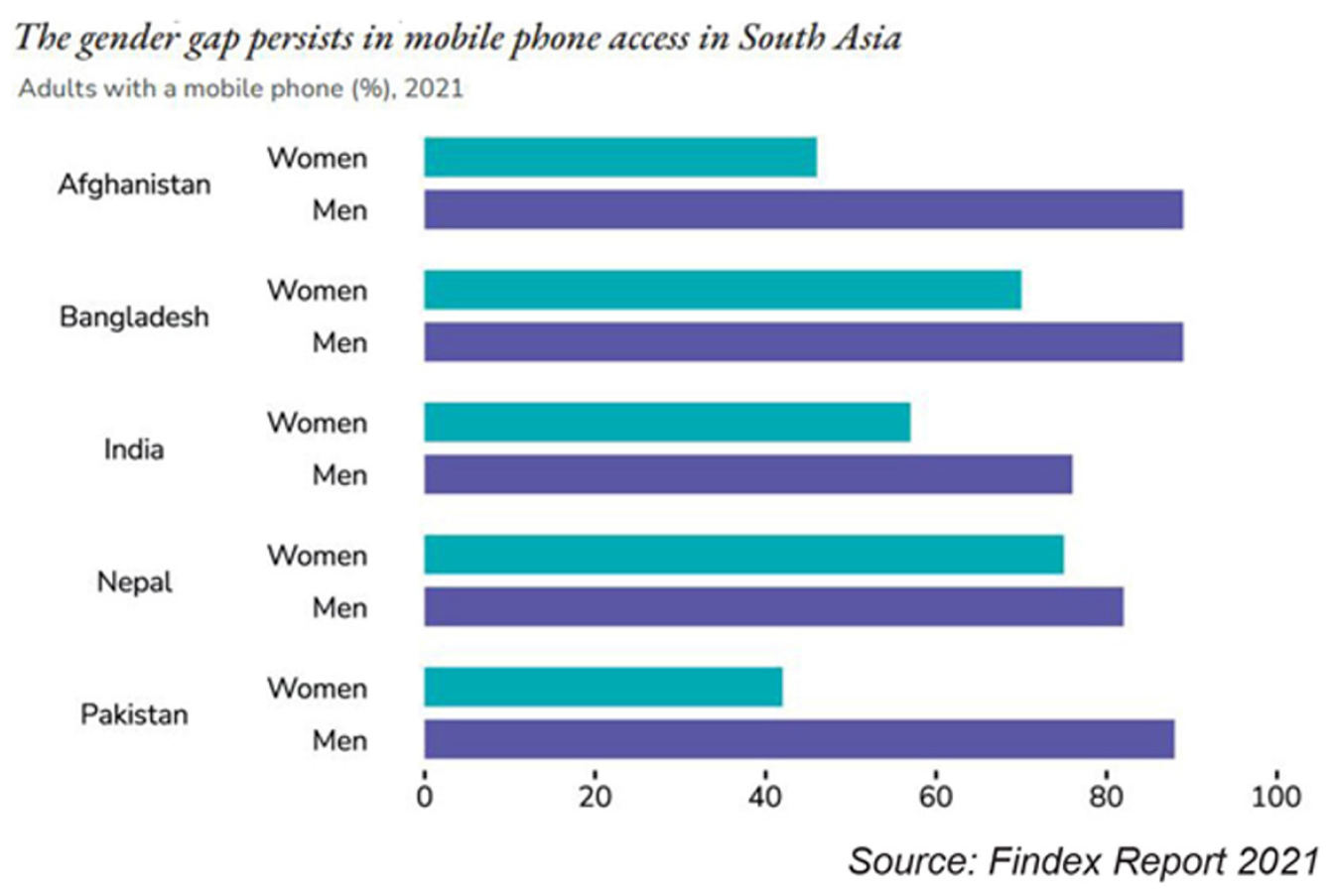

A lot of it has to do with the cultural and social norms, and perceptions about women. For example, in Pakistan there’s a massive gender gap in mobile ownership. Pakistan falls behind even Afghanistan in this regard. The graph below shows these dismal numbers.:

Without mobiles phones there can be no access to digital banking, or even electronic banking because registration requires a phone number. Forget phones, some women don’t even have an ID card.

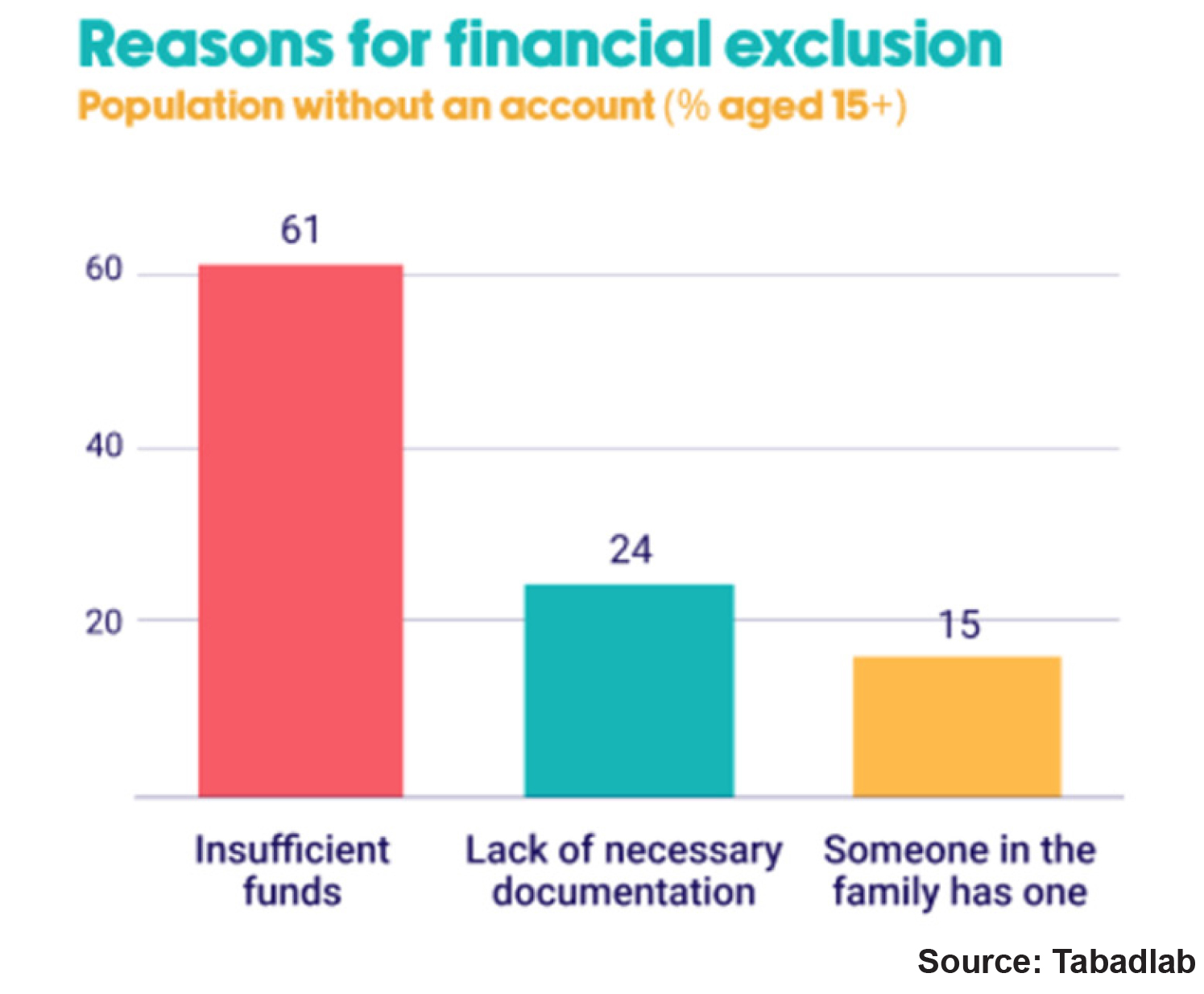

“The biggest hindrance is the cultural restriction. A lot of women who apply for loans don’t have the right documentation, they struggle with something as simple as a CNIC,” said a member of the senior management at a local bank. It’s not that they don’t get it. It’s the overly complicated system that pushes them away from it.

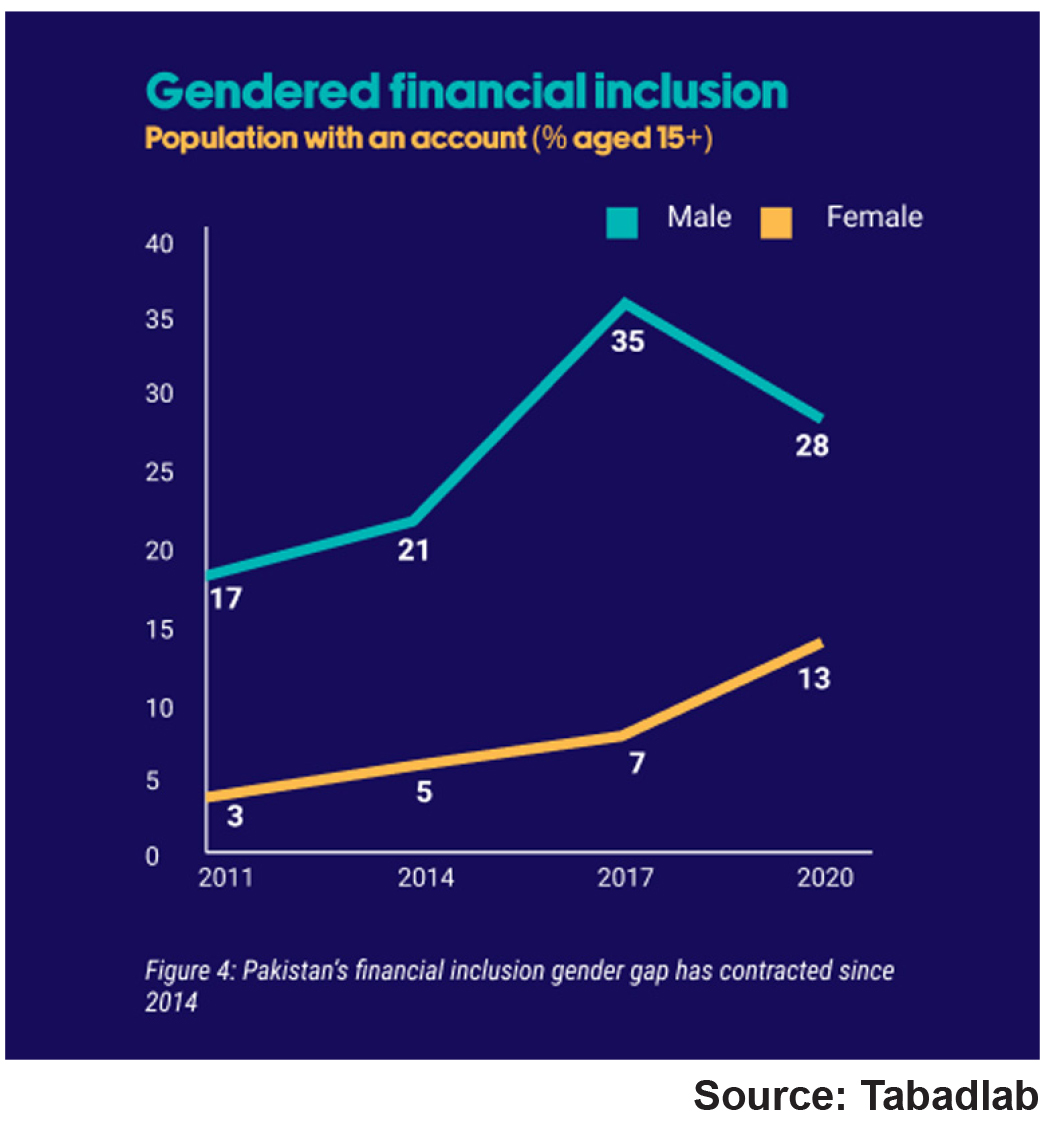

Having said that, numbers show that over the years women’s participation has doubled, reaching a double figure percentage of 13% from 3% in the last decade (look at table below).

This shows that though the gender gap may have narrowed, women’s inclusion is still less than half when compared to their male counterparts. This is because they generally have little to no digital exposure to the outside world, which impedes their access to money and even the right documentation. The following graph explains the reason behind women’s financial exclusion.

With such problems, women turn to other alternatives. According to Halima Iqbal, a former banker in Canada and co-founder of the online committee system Oraan, pooling in money for committees is a more acceptable form of financial services. “They are not just pooling in but are actively participating in various schemes to strategise their spending and loans. The success of committees is because the treasurer is a woman. A lot of women have expressed their concern that they trust a woman to handle their finances,” she said.

Household expenditure is often handed over to women. They devise how to pay bills, school fees, manage groceries and maybe even create savings. Cultural normative behaviour dictates they help everyone and anyone in the family when there is a need so often times they are seen financially assisting extended family members as well. “My maternal uncles have shops so their income is not stable. To kickstart their businesses, I took a loan from the bank of Rs 500,000 and now I face a deduction of Rs 14,500 in my pay every month. Their business is not going too well, so I pay for their kids’ school fees too,” said Hina Abbas, a lady health care worker in Shikarpur.

Abbas’ story busts the traditional myth that women don’t need banking services. When women are involved in formal financial services, there is a trickle-down effect on the community.

How efficient are SBP’s policies?

Realising the utmost importance of women’s participation in the financial system, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) launched a targeted Banking of Equality policy in 2021. The policy comprises five pillars: improving gender diversity in the banking staff, women-centric products and services in all commercial banks, deploying women champions at all touchpoints to make the process easier and smoother for women, collecting of gender-disaggregated data to sharpen focus on financial inclusivity and reviewing existing and new policy frameworks for gender sensitivity.

The policy has thoroughly been applauded by the banking industry. But there are implementation measures which pose challenges, as many women have experienced. “Even now when you go to open a bank account, you will be asked to provide proof of income. It’s redundant for women who are housewives and don’t have official documentation of their money,” said Iqbal.

However, Abid Qamar, the spokesperson of SBP is hopeful. “It will take some time to be fully implemented. We launched Asaan account to cater to this problem. You can register an account on the phone just by entering your NIC number. No extra documents are required,” he explained.

Meanwhile, problems abound. Often, women’s information is breached by the banks. “It is a common practice to call the husband for confirmation when a woman registers their accounts. It has happened to me and so many women I know. Even if the husband is not a customer of the same bank, the bank staff thinks it’s their responsibility to inform how and when their wives are spending money,” highlighted Iqbal. This is a major violation of privacy and is rooted from the general perception that women do not understand finances.

When questioned, officials from different banks requesting anonymity, denied any such happening. One senior member at a local bank in Karachi described it as “hogwash” saying that in her knowledge, nothing like this has ever been done. “Even if it had, we would have vehemently stopped such a practice from perpetuating.”

The SBP’s policy, specifically the part of deploying women champions directly, contests against the overarching belief about women and their access to financial institutions. Profit asked Qamar what to do if the banking staff is not taking a woman seriously, and making the process more confusing for them rather than walking them through it. He replied, “you complain about the bank to us. The State Bank can’t employ their own agents to check what’s happening in each bank. But we do have a helpline and an email address on our website where we encourage everyone to launch their complaints if they are not following the protocol. This will help us review the performances and create better policies.”

But what kind of woman does this policy really help? It seems like it would be very helpful for someone who is financially literate. But what about the woman who has little to no education? What is she supposed to do?

“Of course it does. Every bank is supposed to have women-centric products and services that are designed specifically for your needs. If you visit any bank near you, you will find many products such as HBL Nisa Savings Account, Allied Khanum Account, and MCB Ladies Account. You can find a plan according to your needs,” mentioned Qamar. “The purpose of these accounts along with women champions is to facilitate the banking journey according to different needs and problems,” he added.

However, Profit reached out to some women, who visit banks often and try to avail banking services, and asked if they knew of such products in their banks. Almost every respondent said they had no idea such products existed. The very few who said they knew, expressed a very superficial understanding of what is available. “Yes, I saw a banner of Nisa Savings Account in HBL and something similar in UBL. But I never really inquired about it and no one from the bank told me either,” said Oroba Tasnim.

“Not inquiring is on her,” said the banker from Karachi, “but yes, these products need to be marketed in a way that makes them appealing enough for women to ask about them.”

Not many women know about the services that can be available to them and so are unable to derive any benefit from them. “We are encouraging commercial banks to market these products. It’s not a matter of two or three days. It will take some time. Banks’ performance is assessed based on their efforts to include more women so in a few years we can hope to see the real results,” said Qamar.

The central bank’s policy mandates every woman to have a bank account just with an ID document. But for those who don’t, SBP can’t do much about it. “It’s not under our mandate. It’s an issue that must be addressed by NADRA,” added Qamar.

The only thing that will stand the test of time then is for women to step out of their comfort zone, to visit these banks, to insist on knowing and understanding the products and services to them. But even then, this will help those who are literate and can therefore be pushed into making a change. For underprivileged women, access to financial services seems like a pipe dream.

Agar unhe finanacial azadi nahi rahegi to unhe har chiz puchkar karni hogi.

The Banking of Equality policy launched by the SBP aims to enhance gender diversity, promote women-centric products and services, improve access to financial services for women, collect gender-disaggregated data, and review policy frameworks for gender sensitivity. These objectives reflect the recognition of the importance of women’s participation in the financial system.