The monthly debt bulletin released by the State Bank of Pakistan reveals that Pakistan’s public debt has increased by Rs. 18.5 trillion in only the last 15 months. The total public debt rose by approximately 41% from Rs. 44.4 trillion in March 2022 to Rs. 62.9 trillion by the end of June 2023. Moreover, the Economic Survey 2022-2023, published by the Finance Division, revealed that Pakistan’s total GDP grew at 21.7%, around 20% less than the percentage increase in debt over the same period. However, such calculations may be a misrepresentation of the actual debt figure.

The news speculating concern around this figure is primarily focused on the fact that this Rs. 18.5 trillion debt incurred over just 15 months by the PDM government with Miftah Ismail and Ishaq Dar as Finance Ministers is only Rs. 0.91 trillion less than the total amount of debt accumulated by the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf during their entire three years in government prior to the PDM. The strong opposition between the two political parties has made this a point of great criticism and contention.

However, there are two basic reasons as to why calculating public debt in absolute rupee terms without differentiating between patterns of domestic and external debt can be seen as an unfair representation of a government’s actual economic performance and here’s why:

- Pakistan’s Debt Stock in Absolute Terms

Firstly, the total amount of debt stock (money borrowed is more than the money repaid) in Pakistan will definitely continue to grow for the next few decades regardless of how efficient a government is. The inevitability of the debt stock is a consequence of the country’s inability to generate a revenue that is higher than its spending, which results in it borrowing money. Contrary to popular belief, the revenue deficit is not only due to the public’s refusal to pay taxes, but also stems from a deeper problem within the National Finance Commission (NFC). The NFC, by allocating only 2-5% weightage to tax revenue, has failed to incentivize tax collection and tax generation in Pakistan’s provinces (who the world bank estimates to have a potential of accruing billions of dollars worth of taxes). Therefore, when the Finance Minister is compelled to announce the resource provisions to the Provinces in the Federal Budget, Pakistan’s domestic debt figures immediately increase. This is aggravated by the growing net difference between our imports and exports, which drives our external borrowing and thus, raises our external debt.

Moreover, as long as Pakistan’s external account does not become self-sustaining, i.e, exports do not exceed imports, Pakistan will be looking towards external dollar financing, some of which is bound to be in the form of debt.

Therefore, without structural changes to our commissions, economy, and consumption patterns, the debt stock in absolute terms is simply bound to increase without a direct fault of the government in power.

- Debt to GDP Ratio: A Better Measure

Instead of looking at figures that are predestined to show an increase, the debt crisis can be more realistically assessed through the debt to GDP ratio. By comparing what a country owes with what it produces, the debt-to-GDP ratio reliably indicates that particular country’s ability to pay back its debts.

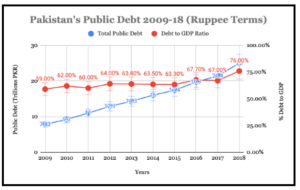

To illustrate, Figure 1 depicts precisely the stark difference between presenting public debt as a percentage of GDP versus in absolute terms. While the trend for total public debt is a consistent increase from 2009 and 2018, the debt to GDP ratio shows that Pakistan’s actual position of repaying its debt is inconsistent and does not follow a fixed pattern. A similar trend would appear for the measures between 2018 and 2023.

Figure 1

The critics who are blatantly criticising the PDM-stint are failing to account for is that even though the total amount of debt increased by a greater amount during the PDM government, total debt as a percentage of GDP was 75.8% in March 2022, while on the contrary, it is currently at 73.6%, which means that Pakistan is actually at a better position to repay its public debt after the PDM government than it was after PTI’s rule.

It is important to note here that the debt stock during this period is more domestic than external, which has its own set of problems, but these problems supersede the binary of “better or worse than the previous government”.

- Accounting for Currency Devaluations: The Best Measure

However, measuring Total Debt as a percentage of GDP without accounting for changes in exchange rates, especially when the changes are as drastic as they were in the last 1 year, is still a simplistic and more importantly, unrepresentative measure. This is because while the total external borrowing may have actually increased by a small amount in dollar terms, due to the rupee devaluation between the two time periods, when the figures are converted to rupee terms and compared, the difference may appear to be exponentially larger than it actually is. This is perhaps the reason why PDM’s public debt figure appears to be as staggering as it is, especially when compared to 2022’s statistics– it may very well be that this overly pronounced figure of Rs. 63 trillion is simply a consequence of the exchange rate increasing from Rs. 205 in July 2022 to Rs. 285 in July 2023.

Let me explain. Public Debt includes the total amount of money borrowed and required to be paid back. This is further divided into domestic debt, which is money owed to lenders within the country in the country’s own currency, and external debt, which is money borrowed from foreign lenders, including commercial banks, governments, or international financial institutions in foreign currency (usually USD). External debt is required to be paid back in the dollars and therefore, likely to be earned in dollars as well, which means that unless the state aims to convert domestic earnings into USD dollar amounts, then the accounting of external debt is not entirely sensitive to exchange rate valuations as is popularly assumed. This means that converting external debt to domestic currency for the sake of calculation of the debt-to-gdp ratio, would sometimes add an undue exchange rate bias.

| Years | Total External Debt

(in USD) |

Total External Debt (in PKR) | Exchange Rate (USD to PKR) |

| 2018 | 95 Billion USD | 13.3 Trillion PKR | 1 USD: 140 PKR |

| 2019 | 106 Billion USD | 18.7 Trillion PKR | 1 USD: 163 PKR |

| 2020 | 113 Billion USD | 19 Trillion PKR | 1 USD: 168 PKR |

| 2021 | 122 Billion USD | 19.2 Trillion PKR | 1 USD: 180 PKR |

| 2022 | 130 Billion USD | 26.6 Trillion PKR | 1 USD: 205 PKR |

| 2023 | 125 Billion USD | 35.6 Trillion PKR | 1 USD: 285 PKR |

Figure 2

The difference in Pakistan’s external debt expressed in USD and PKR for 2022-2023 in Figure 2 clearly presents the problem at play. It depicts that external borrowing under PDM’s government from 2022 to 2023, actually decreased by $5 Billion USD, however since the multiplier amount (exchange rate) increased by almost 23%, when the same figure is converted and presented in PKR terms, the external debt is seen to have increased by Rs. 9 trillion.

Figure 2 also helps us assess the devaluation impact on total public debt calculations, which amounts to approximately Rs. 11 Trillion as is shown in Figure 3. The mathematical working provided below shows that the increase in Pakistan’s total public debt is Rs. 7.6 Trillion when devaluation is accounted for. What this means is that if Pakistan’s external debt in 2022 was calculated under 2023’s exchange rate, then the difference between the total debt in both years would be Rs. 7 trillion less than if the depreciating rupee is accounted for.

| Total Public Debt in Rupee Terms (2022 Exchange Rate) | ||||

| Exchange Rate | External Debt | Internal Debt | Total | |

| 2022 | Exchange Rate 2022 (1 USD: 205 PKR) | 26.6 | 18.4 | 45 Trillion |

| 2023 | Exchange Rate 2023 (1 USD: 285 PKR) | 35.6 | 27.4 | 63 Trillion |

| Difference | 18 Trillion | |||

| Total Public Debt in Rupee Terms (2023 Exchange Rate) | ||||

| Exchange Rate | External Debt | Internal Debt | Total | |

| 2022 | Exchange Rate 2023 (1 USD: 285 PKR) | 37 | 18.4 | 55.4 Trillion |

| 2023 | Exchange Rate 2023 (1 USD: 285 PKR) | 35.6 | 27.4 | 63 Trillion |

| Difference | 7.6 Trillion | |||

Figure 3

Another way to interpret this difference is through the starkly different debt to GDP ratio it provides. Let’s assume Pakistan’s GDP size in 2023 is $380 Billion USD. At current 2023 exchange rates, Pakistan’s total debt to GDP ratio in USD terms [ (External Debt in USD + Internal Debt in USD*285)/(GDP in USD)] is $221 Billion/ $380 Billion = 58%, however, under 2022 exchange rates (1 USD: 205 PKR), the ratio is $126 Billion/ $380 Billion = 33.2%. This means that there is a high probability that the concerning difference in 2022 and 2023 debt figures are simply a result of the volatility of Pakistan’s currency, and do not reflect the actual patterns of borrowing occurred in the last 15 months.

Why is this a problem?

The consequences of misrepresenting the total debt incurred by a government extend beyond mere political point scoring. Not accounting for changes in exchange rates has the potential of contributing further to Pakistan’s endemic problem of artificially overvaluing the Rupee. As explained above, the Rs. 18 trillion difference in 2022 and 2023 public debt is very likely a result of Pakistan’s depreciating exchange rate. However, if the PDM government continues to be criticised for this figure, it might signal to other governments that currency pegging or fixing the PKR to USD value will improve their performance metrics.

In reality, this is perhaps one of the reasons that has led Pakistan’s economy to being where it currently is. Shaping our economy to be import dependent and consumption based has meant that Pakistan’s economic growth has thrived when dollar denominated goods have become cheaper. This has caused a consistent stream of Finance Ministers aiming to keep the dollar cheap against the rupee, despite the serious trade deficits that we have had to incur in the process. Ultimately, this has resulted in exchange rate explosions, in the form of drastic rupee devaluations in the internal market. The focus, therefore, should be on encouraging governments to allow the currency to adjust according to free market forces, as opposed to forcing them to fall back to old, politically beneficial, short-term policy patterns.

Comments are closed.