Imagine this: you are a policy maker who decides you want to draft a policy which supports and helps employment opportunities for disabled people in Punjab. It’s a great cause and you’re excited for the impact it will bring. But when you sit down to draft the policy you find out there’s no way to draft any policy for this group, let alone a policy targeting employment opportunities, because there is no accurate record of the total number of disabled people in Pakistan.

The truth is, if you’re actually a policy maker in Pakistan dealing with census data, you probably don’t have to stretch your imagination too hard for this scenario. And the worst part is, you also will not know what government organization to blame, or even how to gather the data yourself.

How can you run a country if you don’t have any data about it? That is the question underlying all of the research presented in the State Bank of Pakistan’s 23-page primer titled “Pakistan’s National Statistical System”, as part of its annual report for fiscal year 2023-2024. The word ‘primer’ is key here: as the authors themselves note, “Pakistan’s statistical system is an under-researched subject, hence this special chapter is entitled as a primer. It undertakes a broad assessment of the country’s statistical system, and is not intended to be exhaustive in nature.”

This lack of research is reflected in a myriad of ways: statistical reform is not a topic of consideration within economic discourse in the country, either in economic policy publications of the last decade in Pakistan, or in the charters of economy proposed by various policy research and advocacy organisations.

And yet, precisely because it is so under-researched, this is in fact, the most exhaustive document thus produced by a government institution on the state of Pakistan’s statistics. The consensus is sobering; on almost every indicator, Pakistan is lagging behind its peers in the region, and setting back its own development goals by decades.

Why are statistics important?

Before we dive into Pakistan’s current statistical system, and its problems, it’s important to understand why the SBP is flagging this issue to begin with. The truth is, raw quantitative data is a crucial indicator of a country’s developmental standards, but it can be further transformed into a tool for deep comparative analysis and impactful policy making.

The primer identifies three distinct ways that statistics are utilized for effective governance and development. First, as key building blocks for evidence-based policymaking; data is often used for mid-course corrections, policy calibrations, and impact assessment. Second, to disseminate market information and reduce asymmetries that leads to greater market efficiency and optimization, which is helpful for businesses in the country. And third, to catalyze competition at a sub-national level by providing means for regional comparisons by tracking performance against quantifiable targets, such as economic growth and unemployment. If you have better statistics, for instance, you can more accurately compare unemployment levels between different districts in Sindh, and thus create targeted policy improvement.

Remember that hypothetical struggling policy maker referred to in the introduction? Let’s bring them back and illustrate a real-life scenario of why statistics are important.

A 2014 British Council report revealed that in 2014 Pakistan lost almost 6.3% of its gross domestic product (GDP) owing to the exclusion of persons with disabilities. The loss was also quantified to be an economic cost of $33 million per day– almost Rs 9 billion under the current exchange rate. Just a few years later, in 2017, after a nine-year gap, the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) carried out the sixth population and housing census.

Yet despite the approximate cost of Rs 14 billion and the deployment of 200,000 army personnel, experts held the census to be inadequate due to the absence of vital data on indicators – including disabilities.

Pakistan is losing out on a vital contributor to the economy – all because of a lack of effort for pre-census preparatory operations.

What is Pakistan’s NSS?

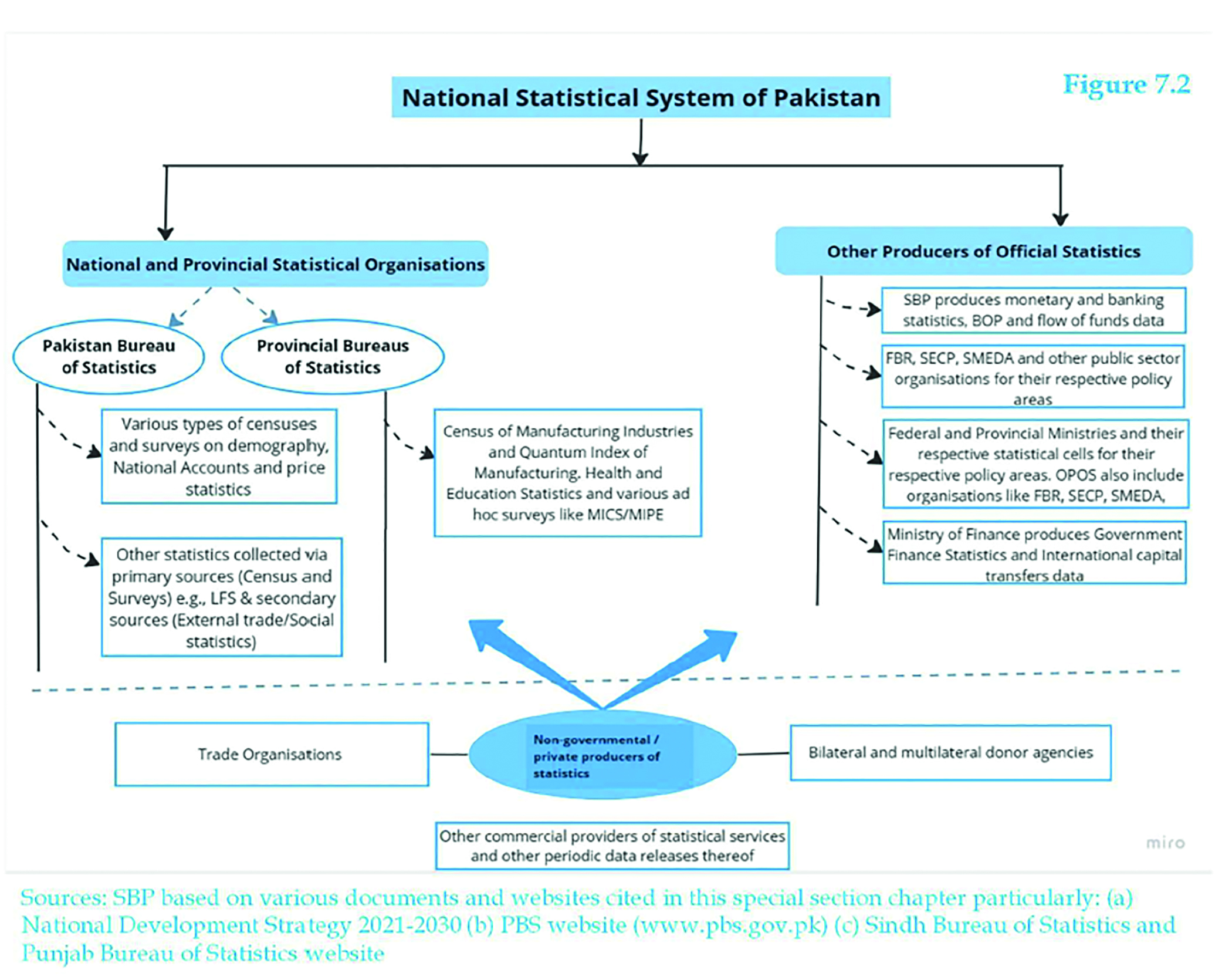

There is really no set definition of a National Statistical System nor a global consensus on its structure. That being said, an NSS is largely understood to be an ensemble of public sector organizations, ministries and departments of a country that jointly or separately collect, process, and disseminate official statistics. It can be highly centralized, such as in Canada or China, or decentralized, such as in the United States and Germany.

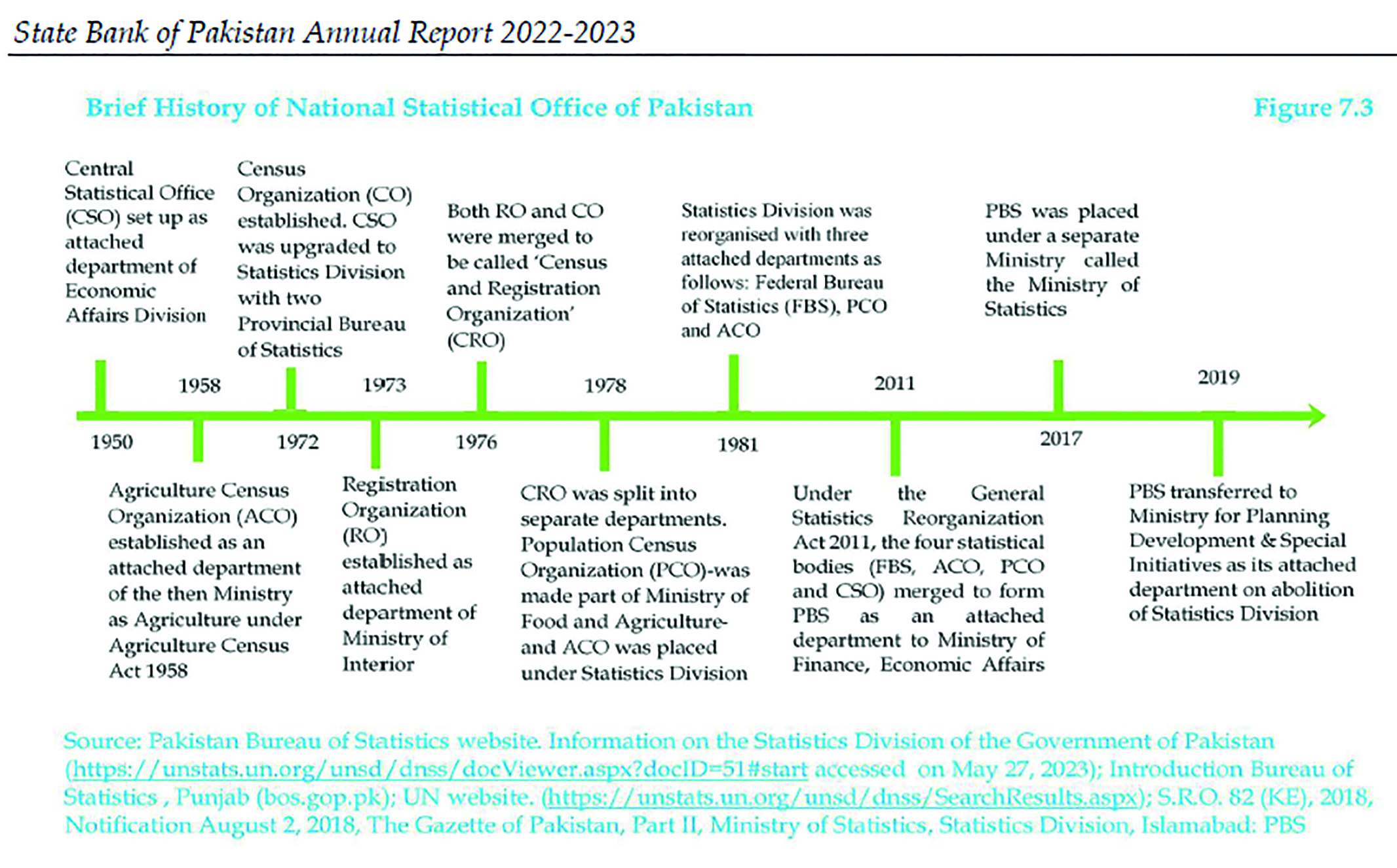

In Pakistan, the NSS takes an intermediate position divided between a centralized and decentralized statistical system. The PBS, headquartered in Islamabad, serves as the central agency of the country’s NSS, and is primarily mandated both to collect data and statistics, as well as to coordinate statistical activities at the national level. The PBS covers things like the population and housing census, livestock census, and the Pakistan demographic survey.

The NSS also includes four Provincial Bureau of Statistics (PBoS), one in each province, and two statistical cells at Gilgit Baltistan and AJ&K that do not have full-fledged bureaus.

Then, there is also the ‘Other Producers of Official Statistics’, some of which you will already be familiar with. These include the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR), the Security Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP), the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), and registries like the National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA) and the Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP),

The primer tests the effectiveness of the PNSS on three distinct fronts: independence, coordination within the statistical ecosystem, and the availability of administrative data. Unfortunately, the PNSS ranks lowly across all three metrics.

With regards to its independence, the PBS continues to be an attached department of the Ministry of Planning Development and Special Initiatives. Similarly, the PBoS are also working as attached departments of the respective provincial planning and development departments.

With regards to its coordination, the primer states, “coordination mechanism among and within the statistical organizations is weak. While there is some level of coordination within the NSS, such as for large census, surveys and key indicators, these interactions are on adhoc basis. There are no permanent institutional and legally mandated platforms for coordination.”

And finally, with regards to administrative data, Pakistan also falls short with very limited access to and collection of admin data.

What is wrong with Pakistan’s statistics?

So a constrained, disorganized NSS, with the PBS and ‘Other Producers’ not coordinating efficiently with each other: what could possibly go wrong? Quite a fair bit.

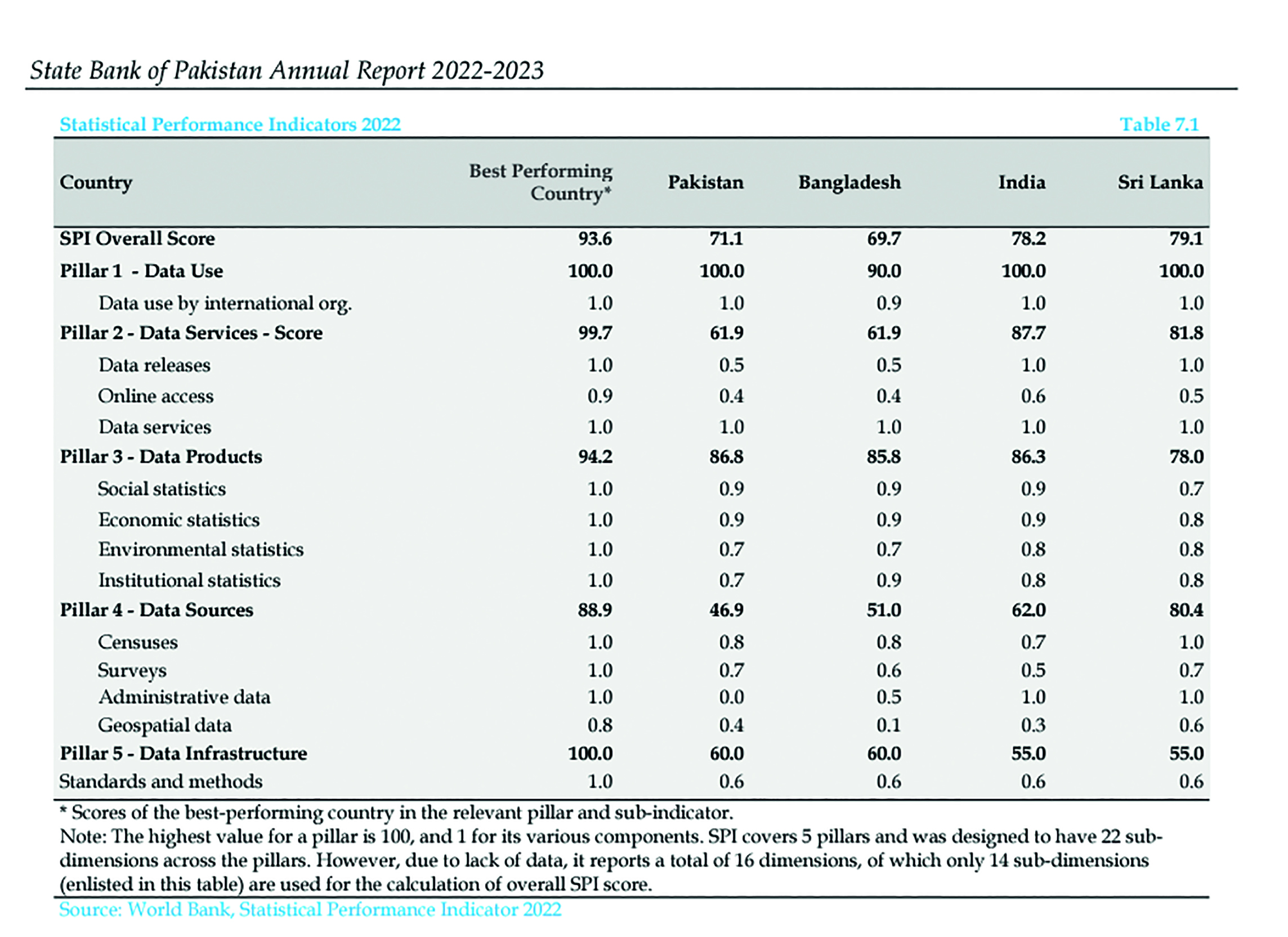

While there is no global consensus on what an NSS can look like, there is a globally agreed standard for data dissemination, against which Pakistan’s official data is measured against. Specifically, one can look against the World Bank’s Statistical Performance Indicator (SPI), which is an indicator used to assess the maturity of a country’s statistical system on an overarching framework across five pillars: data use, data services, data products, data sources, and data infrastructure.

Of the 186 countries ranked on the SPI, Pakistan is ranked 87th. The three pillars of SPI in which Pakistan performs well are data usage, data products and data infrastructure.

Its lowest score, however, is for data sources which is attributed to the weaknesses in its utilization of geospatial and administrative data. Pakistan’s SPI score for data sources is 46.9– for comparison, the highest performing country has a score of 88.9 for the same measure.

The primer then hones in specific issues in data collection. It is not that the country does not collect data: it is that it is so haphazard, that each sector of the economy has massive statistical gaps that need to be addressed. We will walk through each one in this section.

Take for example the GDP. In a 2022 survey of 170 countries, Pakistan was one of the 26 nations that did not produce quarterly estimates of GDP. Meanwhile, according to the primer, sub-national or provincial GDP figures are also not reported, despite the 18th Constitutional Amendment that devolved several policy areas to provinces.

Pakistan’s small and medium enterprises (SMEs) contribute nearly 40% to the GDP and 25% to texports. Yet all data about SMEs comes from the Census of Economic Establishments of 2005, after which no census was conducted.

This kind of lack of data leads to spillover effects, such as inadequate tax collection. The primer noted that in 2019, a lack of consensus between the tax authorities and the textile association over the domestic market size of textile products – a basic market statistics – led to resistance in the reversal of zero rating of general sales tax (GST) on the industry.

Pakistan also does not collect data on high-frequency economic indicators (HFEI). These are often short term indicators that spot turning points in business cycles. Examples of non compiled data include federal taxes withheld, hotel occupancy, retail sales, comparable-store sales, highways tolls, building permits, domestic air passenger and cargo traffic, and indexes tracking online job market placements.

The absence of such data hampers industries trying to enter new markets. According to the primer, “soft information suggests that prospective Chinese investors eyeing investment opportunities in various sectors under the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) also face similar challenges.”

On labour and employment data, Pakistan has conducted only 36 annual Labour Force Surveys and eight quarterly surveys since 1963. Compare that to India and Sri Lanka, where those surveys have been conducted quarterly since 2018 and 1990 respectively. So, imagine this: Pakistan’s policy makers are confronted with the mammoth task of drafting a basic unemployment benefit policy simply because there is a complete absence of key labour statistics, such as of total unemployment and average wage for each population quintile group.

Although Pakistan does measure and release the Consumer Price Index (CPI) on a monthly basis, it does not do so on a quarterly basis nor does it report the Producer Price Index (PPI). The PPI can serve as an early indicator of inflation. Countries like Sri Lanka and Bangladesh regularly publish the PPI.

Additionally, Pakistan’s ranking in the category of crime and justice data is poor due to the unavailability of indicators on homicide rates, prison populations, and limited coverage of crime rate data.

Interestingly, across all major data categories, the overarching problem seems to be a considerable time gap in data collection. As stated in the primer, “the last agriculture census in Pakistan was held in 2010, a notable time gap of more than 10 years, whereas frequent floods, climate change and changing market dynamics warrant more frequency of such surveys.” Similarly, estimates of livestock, which contribute 14% of national GDP, are based on surveys conducted between 1996 and 2006.

But perhaps the biggest indictment of the national statistical system is this: that we do not accurately know how many people in the country are born, or when they die. Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) is the process of collecting information on vital events such as births, marriages, migrations, deaths, and causes of death. But this is limited in Pakistan. According to the primer, it is estimated that approximately 42% of children under five years old are officially registered, and only 36% possess a birth certificate. Similarly, less than 5% of deaths in the country are registered.

It’s not all doom and gloom (yet)

The primer’s authors offer some consolation. First, there has been some consideration by the PBS itself, which recently prepared the National Strategy for the Development of Statistics (NSDS) 2021-2030 The NSDS 2021-2030 lays out a road map for the development of official statistics in the country including areas of coordination, capacity building of statistical practitioners in the NSS, and improvements in data collection.

Still, the document does not spell out detailed assessments of the challenge of coordination, or state of provincial bureaus of statistics. Besides, assessing and proposing reforms is not the main job of the PBS; its main job is to actually conduct census and surveys.

So the primer points to examples in two countries. When India embarked on statistical reforms in 2000, it formed a National Statistical Commission with representation of key stakeholders across the country. This was the body that prepared reports on specific data deficiencies, and ended up covering nine broad categories of statistics including corporate sector statistics, national accounts, and infrastructure statistics.

Similarly when the US undertook an assessment of its administrative data in 2016, it passed a law to form a Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking. The commission had fifteen members, three each to be appointed by the president, speaker and minority leader of house of representatives, and majority and minority leader of senate.

Perhaps Pakistan could form a body or commission that could then work and improve upon NSDS 2021-2030?

The other option available to Pakistan is to heavily ramp up its collection of administrative data. Traditional statistical sources include surveys and the census; but administrative is the kind of data that is derived from digitalization of government records, and increased computer usage generally in the government and public sector organizations. This could then provide the much needed shortcut to quality data.

Administrative data is useful for three reasons: first it offers near-actual information rather than only estimates, on businesses, markets and individuals at the micro level; second, it is high frequency, ranging from quarterly and monthly to even weekly numbers; and third, it helps authorities to address informality via triangulation and corroboration of data.

Pakistan already has rich sources of administrative data. These include NADRA (civil registry), BISP (social registry), SECP (company’s registry), education records at the Higher Education Commission and various education Boards, FBR (tax data), records of tax bodies that levy provincial GST on services, vehicle registration records, and automated land records in Sindh and Punjab.

That is a minefield of data just waiting to be integrated into the NSS. As a helpful example, the primer suggests coordination between the PBS and tax authorities, particularly after the 7th Housing and Population census, which had been conducted digitally for the first time in the country’s history.

“The tax authorities, the FBR and provincial tax bodies for GST on services, along with the SECP and district offices that hold records of Association of Persons and partnership firms can jointly maintain a business register. To this end, the PBS can provide guidance on data quality, industry classification, harmonization and standardization, while tax authorities, the SECP and district offices can provide their respective data.” the primer reads.

According to the primer’s authors, this would help PBS with preparing its quarterly national accounts, and would help the FBR broaden their tax base.

Still, it is only one example. Justifiably, the primer has not spared pointing fingers at Pakistan’s NSS, which it states falls behind in comparison to both best practices and peer economies in the region. Data on crucial subjects, such as GDP and unemployment, is either absent or insufficient in frequency. And the timely measurement and availability of these statistics is even more integral for a developing country like Pakistan, where these indicators are viable to change and often require immediate actions and solutions. Pakistan desperately needs to get its act together – and start counting some numbers. Our policymakers rely on it.

There is the reason behind our poverty.

No reliable statistics , no poverty , all good

It’s disheartening to confront the reality that as policymakers, we often find ourselves in a paradoxical situation where our intentions to enact positive change are hindered by the lack of foundational data. The scenario presented, wherein drafting a policy to support employment opportunities for disabled individuals in Punjab becomes an insurmountable challenge due to the absence of accurate census data, epitomizes the pressing issue of data deficiency in Pakistan’s statistical landscape.