We can’t quite track down the first genius that planted this seed, but Pakistani policymakers have long been obsessed with the health of the Rupee. The result has been a consistent pattern in which different governments have tried (and failed) to control the rate of the rupee.

Some of the aversion to letting the rupee settle at its natural rate has to do with an aversion to the basic principles of economics. So rather than improving the balance of trade, governments have tended to force and bully the rupee to adhere to artificial rates that seem good on paper.

The latest saga of trying to wrangle the rupee began somewhere around 2018 when the Imran Khan administration came to power. At the time, the rate of the Rupee was Rs 121 to the dollar. In the six years since the rupee has gone to highs of Rs 310 on the interbank and is currently settled comfortably at just under Rs 280 to the dollar.

So what exactly happened to the rupee in these six years? To cut a very long story short, international pressures such as the Ukraine War and domestic concerns such as an overheating economy and inflation demanded that the rupee weaken. At the same time, a string of finance ministers unwilling to lose political capital for their respective parties demanded that the rupee stay stable one way or the other. At the same time, currency markets in the country practically imploded, and it took intervention of the entire state machinery to set things back in order.

Now, Pakistan might once again be at a similar crossroads. War is stirring in the Middle East, a contentious American election is to be held in a few months, global oil prices are on the rise, and there is a weak coalition government in Islamabad trying to control inflation. So what will it be this time? Will the rupee hold, and if it doesn’t, will there be someone trying to prop it up again?

A brief history of a terrible idea

This isn’t the first time Profit is covering how the exchange rate functions in Pakistan and all of its many implications. Back in 2018 when the Imran Khan government had come to power, this publication had prescribed that if the rupee was falling, it should be allowed to crash.

The history of why this might be a good idea goes back to the first time Pakistani policy makers decided the strength of the rupee was some kind of indicator that had to be kept inflated. And it started a long time ago thousands of miles away in a stuffy room in central London.

On September 18, 1949, the Bank of England made a monumental decision that set off a series of events that has permanently reshaped the Pakistani economy. On that day, the British government announced that it would be devaluing the pound sterling by 30%. In those days, while the US dollar had already taken over as the default currency of global commerce, most former British colonies still pegged their currencies to the British pound. As a result, when the British government decided to devalue the pound relative to the US dollar, the government of India decided to follow suit. Crucially, however, (and this, in hindsight, was a blunder of monumental proportions), Pakistan did not follow suit.

The government of Pakistan at the time felt that it did not want to devalue the rupee because it felt that Pakistan’s own macroeconomic indicators did not justify such a move. That decision, however, had a serious negative impact on the Pakistani economy.

For all the details: The rupee is falling. Let it crash.

To cut a long story short, when India devalued its currency and Pakistan did not, suddenly Pakistani goods became more expensive to produce relative to their Indian competitors, by a factor of 30%.By choosing to prioritise the absolute level of the exchange rate over the consequences for the rest of the economy, specifically the country’s nascent export industries, the government permanently altered Pakistan’s economic trajectory. Instead of integrated regional supply chains (which, by the way, survived the 1948 war just fine, suggesting that Pakistan and India can go to war and continue to trade at the same time), Pakistan is now mostly cut off from its regional markets and has set back the development of its export industries by decades. Here is where things get interesting: the government of Pakistan did ultimately have to devalue the Pakistani rupee. In August 1955, the rupee declined by 44.2% relative to the US dollar in just one day, more than it would have, had the government decided to retain its parity with the Indian rupee and maintain its exchange rates with its main trading partners.

Trying to plug the leak

It wasn’t that the problem couldn’t be solved once it happened. No. The problem has been consistently trying to do the same things to manage the problem. For the first couple of decades Pakistan maintained its fixed exchange rate regime.

The situation changed when the country had to seek the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) help to manage the balance of payments position in 1981. As per IMF advice under Article IV consultation, Pakistan was asked to adjust its exchange rate significantly and gave Pakistan two options: either to make a one-time adjustment or a daily gradual adjustment.

Pakistan opted for the latter and switched to managed float in January 1982. Under this regime, the the exchange rate was set on a day-to-day basis, keeping in view (i) the exchange rate movements of Pakistan’s fourteen major trading partners, (ii) the exchange rate movement of 32 major export destinations of Pakistan, and (iii) the exchange rate movement of export competing countries.

Since 1982, almost every single government (with only one exception) has tried to artificially control the price of the rupee as a means of keeping inflation lower than it naturally would be if the exchange rates were left alone. Every time, the cycle is exactly the same: the government raises foreign debt as a means of securing more dollars, which it slowly sells over time so that it can create an artificially high supply of dollars in the economy and artificially high buying of the Pakistani rupee. This is obviously unsustainable, largely because the government is using borrowed money not to finance investment into future income opportunities for the economy but present consumption. Eventually, foreign lenders want their money back and are not willing to refinance, and hence the government’s ability to prop up the rupee ends, causing the currency to suddenly crash.

Pakistan followed managed float till mid-2000. After the nuclear blasts in May 1998, Pakistan switched to a dual exchange rate regime for a short time. In July 2000, Pakistan switched to a free float exchange rate regime and is officially following this regime till now. In this regime, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) intervenes in the foreign exchange market from time to time to smooth unnecessary volatility and quell speculative attacks on the exchange rate.

Though the SBP officially follows a free float exchange rate and intervenes in the foreign exchange market only to curb disorderly market conditions, analysts have criticised that it is not pure free float but rather a ‘crawling peg’ – an exchange rate regime that allows currency depreciation or appreciation to happen gradually.

A history of Darnomics

Perhaps nothing is as synonymous with controlling and managing the exchange rate in a bid to stay away from inflation than the name of Ishaq Dar. The four time finance minister who is now the foreign minister (and somehow still obsessed with propping up the rupee at a historic time in international relations) has created his own brand of economics based around a strong rupee. He has been responsible for plenty of disasters under his watch to do with the rupee. However, Darnomics actually precedes Dar.

And while all governments have tried to do the same things, perhaps the most egregious attempt to control both the exchange rate and inflation was in the Musharraf Administration, which sought to maintain an exchange rate of approximately Rs60 to the US dollar for nearly the entirety of its term in office. Inflation during that time averaged a relatively tame 6.6% per year, though the rate had started coming down under the latter part of the second Nawaz Administration and started creeping up in the last year of the Musharraf Administration. The full extent of the pain caused by the Musharraf government, however, was not felt until the Pakistan Peoples Party, led by then-President Asif Ali Zardari came into office in 2008. In the very last month that President Musharraf was in office – August 2008 – inflation hit 25.3% on an annualised basis. The rupee lost a third of its value in one year.

However, this was still fixable. Perhaps the only government that made almost no attempt to control the rupee’s exchange rate was the Zardari administration, which let the rupee be a truly market-based free float. But international oil prices meant there was soaring inflation from 2008-2013 as well. Despite making no attempts to control the exchange rate, inflation remained higher than the historical average, and clocked in at an average of 13.2% per year.

Which is why when Nawaz Sharif came to power in 2013, he came with the promise to regain control of the exchange rate. He came in with Ishaq Dar as finance minister, and that meant the formal inauguration of Darnomics. Even though the Zardari administration had broken the habit of controlling the exchange rate, there was no stopping Senator Dar.

The third Nawaz Administration famously tried to peg the rupee at Rs100 to the US dollar, and mostly succeeded in doing so, though at the cost of rapidly increasing the foreign debt burden of the country. While inflation averaged just 4.9% during their tenure between June 2013 and July 2018, it is too early to tell just how much the damage will be in terms of currency depreciation and inflation, as a result of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and Finance Minister Ishaq Dar’s decisions.

Dar took the helm of the finance ministry in 2013 at a time of favourable external conditions when crude oil was especially cheap in the international market between 2014-2017 going below $50 a barrel. Besides, the PML-N was fortunate to get Generalised Scheme of Preferences Plus status in 2013 and managed to bring down the trade and current account deficits. These lower prices combined with a lower debt burden meant that Dar was able to loosen the government’s purse strings to catalyse growth and lower inflation in the short term.

Most of the growth was led by government spending on development projects, which raised problems of long-term sustainability. Pakistani exports dropped from $25 billion in 2013 to $22 billion in 2017, according to central bank data, stretching Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves and putting further stress on the country’s current account deficit.

By the time Nawaz Sharif was ousted by a judicial order in 2017, inflation was rising and the government needed to borrow more money to pay back its debt. From July to October of 2017 alone, the federal government obtained $2.3 billion in foreign loans, including $1.02 billion in commercial loans. The country’s official foreign currency reserves, which peaked at $19 billion, slid on the back of foreign borrowings to $13.5 billion as of November 17, barely enough to finance two-and-a-half months of imports.

A big reason for this was Dar’s insistence on pumping the market with dollars to keep the value of the rupee high. This of course caused the economy to start becoming a bubble. Because the rupee was overvalued, people went crazy on importing and the consumption-led growth continued leading to a classic case of overheating. The only recourse was going to be a sudden correction, a decrease in imports, a slowdown in economic activity and eventually an implosion.

Then Dar made a comeback to the finance ministry in 2022. He became finance minister in September 2022 and served until August 2023. Immediately after he took office, he declared the Pakistani rupee as undervalued and vowed to reduce interest rates, fight inflation, and strengthen the exchange rate. Dar was confident who during a television interview said “he knew how to deal with the IMF” since he had been doing it for decades, decided to artificially keep the price of the rupee high.

However, a few months down the lane, the reality set in as the promise of bringing down the dollar to below the 200-mark fell by the wayside.

Soon, the country began facing a shortage of forex reserves that led to a curb of imports and skyrocketing inflation. In January 2023, Dar had to surrender to secure the last tranche of the of $1.1 billion of the $6.5 bailout package approved in 2019 and the rupee depreciated and reached an all-time low of Rs 262.6 per US dollar in the interbank market as the country abandoned controls on its exchange rate. The nosedive continued in February, as the rupee experienced a sharp decline, plunging to a rate of Rs 275.5 per dollar and causing significant disruption in the market. During this time foreign exchange reserves dropped from $8 billion to a dangerously low of less than $3 billion.

Stand By Agreement (SBA)

The country was teetering towards a default. Pakistan avoided a default by securing a last-minute staff-level agreement from the IMF for a SBA on June 30, 2023. At the time, the country’s forex reserves plummeted to approximately $ 4.5 billion, covering not even a month’s worth of imports.

However, the currency market had other plans, as even after the disbursement of the much-needed funds, speculators ran rampant and the rupee lost significant value, breaching the Rs 300 mark. This trend was curbed in September 2023, as a nationwide crackdown on speculators led to a sharp correction in the market.

This action was also necessitated by the fact that the IMF SBA required Pakistan to maintain the gap between the interbank and open market rates at a maximum of 1.25%. The idea behind this condition is simple: the IMF suspected that the SBP in the past had been coercing the banks into keeping the dollar rate artificially low in the interbank market. The IMF was apprehensive about this intervention, as it encouraged imports and discouraged exports, worsening the dollar reserve situation.

Therefore, post corrective measures, the rupee gained value significantly and the exchange rate outlook remained positive in the short run. The exporters also became cognisant of the trend and ran to the forward market to hedge their risk.

The exchange rate has been largely stable in the last few months. However, recently there were some speculations of the Pakistani rupee appreciating and strengthening to Rs 220-230 against the greenback. Historically, that has been the case whenever PML-N comes into power: the Pakistani rupee has strengthened due to questionable economic practices like Dar-peg, as mentioned earlier.

However, these speculations are making rounds amidst a time when the rupee has been declining against the dollar. The domestic currency has been depreciating marginally against the greenback for consecutive three days against the greenback between April 15 – April 17 2024 in the interbank market. (more on that later)

New IMF program

Pakistan is currently headed towards the next International Monetary Fund (IMF) Program which is crucial for the economic stability of the country. The country is stuck in a low growth and high inflation cycle. Finance Minister Aurangzeb is in Washington where he will be attending the IMF-World Bank spring meeting, and also start negotiations for Pakistan’s 24th long-term IMF bailout.

The next IMF Program is crucial for the economic stability of the country. Pakistan faces around $25 billion in external financing needs in the next fiscal year commencing from July, which is around three times the country’s current foreign exchange reserves.

Failure to secure a fresh IMF program could also result in a repetition of the country nearing default as it did last year in June 2023. This would likely negatively impact investor confidence in the country’s macroeconomic outlook.

Historically, massive currency devaluations have accompanied some of Pakistan’s previous IMF loans and are often a condition of the lender’s programs around the world. This is because usually the rupee was artificially appreciated through government and central bank intervention.

However, as per a report by Bloomberg, Finance Minister Muhammad Aurangzeb, does not anticipate any significant currency devaluation as part of its negotiations with the Fund. He cited strong foreign exchange reserves and the stability of the exchange rate as contributing factors to this assessment.

As of April 18, the State Bank of Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves stood at $8 billion despite $1 billion repayment of international bonds.

While Aurangzeb added that there is no reason for the rupee to depreciate by more than 6% to 8% seen in a typical year, he, however, cautioned that the only wild card would be the oil price.

Why has the currency depreciated?

The Pakistani rupee, along with most Asian currencies depreciated following Iran’s retaliatory attack on Israel over the weekend, causing tension in the region of escalation of war.

The conflict-ridden situation in the Middle East has begun to impact the domestic currency, as oil prices continue to escalate. As an oil-importing country, Pakistan can be impacted by the rise in oil prices, particularly in light of the precarious balance of payments.

However, there is a silver lining amidst the uncertainty. Oil prices witnessed a decline after Iran signaled that it no longer deemed retaliation against Israel necessary. Nevertheless, it’s important to acknowledge the significant global uptrend in oil prices over recent months. For instance, as per a news publication, Arab Light Crude is presently trading around $92 a barrel, reflecting the ongoing volatility in the oil market.

Global foreign exchange market

Internationally, the greenbacks have been strengthening while emerging markets currencies have plunged this year driven by the soaring US dollar following the US Federal Reserve’s decision to raise the interest rates to a historical high.

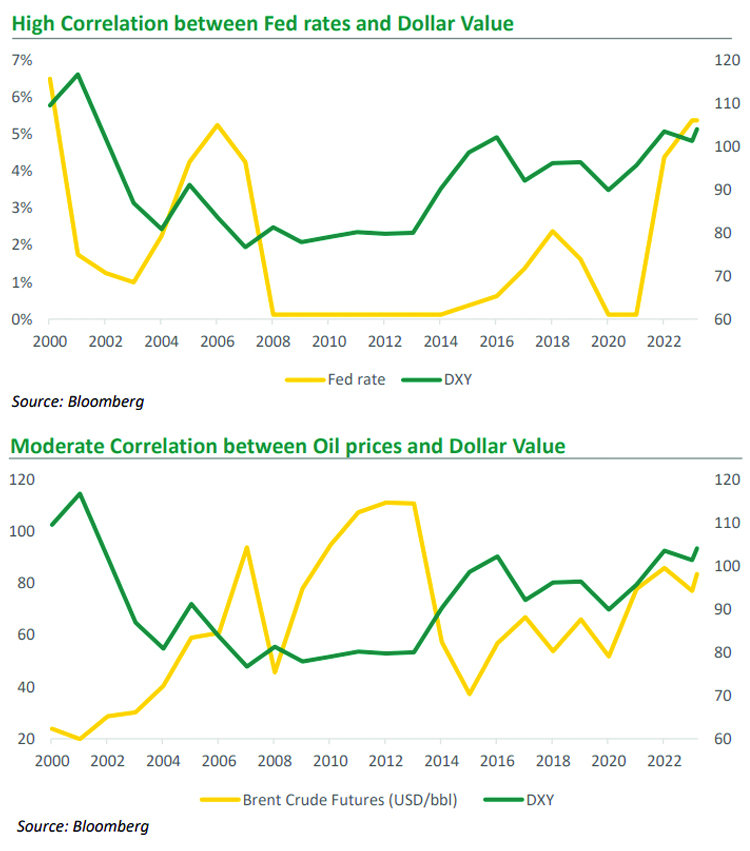

When interest rates in the US are high, investors tend to gravitate towards US assets like government bonds, stocks, and corporate bonds which leads to an inflow of foreign capital into the US financial markets, resulting in the US dollar appreciation.

This has been proven by history. As per KTrade Economic Insight Report titled “Assessing the Future Trend of the US Dollar & Global Currency Flows”, following the Tech bubble burst in 2000, the Fed cut interest rates sharply, reducing the average Fed rates from 6.5% in 2000 to 1% in 2003. Consequently, the US dollar depreciated significantly, dropping from 110 in 2000 to 87 in 2003.

Conversely, during the US economic resurgence post-COVID-19, the Fed raised interest rates from 0.125% in 2021 to 5.375% in 2023 to manage inflation. This resulted in the dollar index climbing from 96 in 2021 to 101 in 2023. According to the Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index, which tracks the US currency against 12 of its major peers, it has surged by more than 4% this year.

Moreover, as the US economy outperformed global growth, investors scaled back expectations of Federal Reserve rate cuts. This has helped boost gains in the greenback.

According to a Bloomberg report, the upper limit of the Fed’s benchmark stands at 5.5%, offering investors lucrative returns without the need to bear the exchange-rate risk associated with investing in emerging markets, resulting in increased demand for dollars.

Moreover, the expectation of sustained high US rates has dissuaded Asian central banks from reducing their benchmarks, driven by concerns over potential currency depreciation.

Source: KTrade

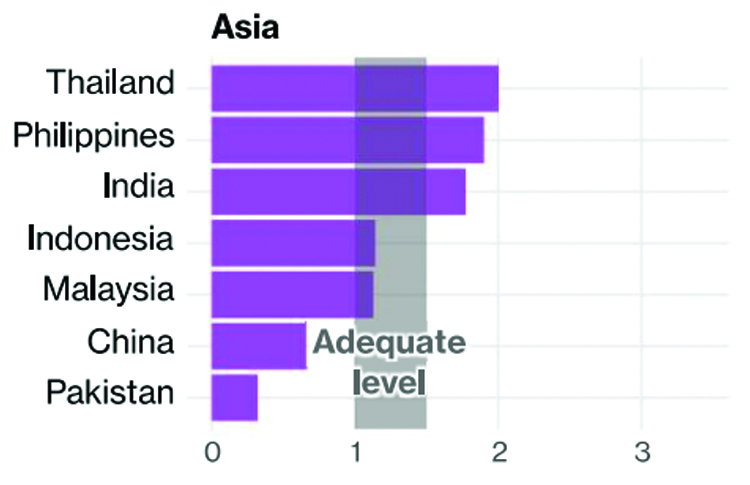

Depreciation of currency has implications for central banks and governments of emerging economies that have to service debts issued in dollars. Around $54 billion in emerging-market hard-currency notes are due in 2024, according to Bloomberg data. However, the silver lining is that many of them have adequate reserves to weather the situation.

Unfortunately, that is not the case with Pakistan. As per Bloomberg, the IMF’s standard of “adequate” buffers is when the countries hold enough reserves to cover three months of imports. However, Pakistan forex reserves as of April 12, cover only 1.88 months of imports.

Inflation, money supply and Rupee

Pakistan’s central bank jacked up the policy rate cumulatively by 15% between September 2021 to June 2023. The final increase came in June 2023 when the State Bank increased the policy rate to the highest level of 22%. The aggressive monetary stance of the SBP was influenced, at least in part, by the conditions set by the IMF. These conditions require the implementation of an appropriately tight monetary policy, aimed at curbing the price riding levels.

In March 2024, inflation was recorded at a two-year low level of 20.7%, from a peak of 38% in May 2023. For the first time after a gap of 37 months, the real interest rates, – the current interest rate minus the inflation reading – turned positive by 1.3%, falling below the interest rate that stood at 22%. However, high inflation rate in the last two years has led to demand destruction.

Moreover, while inflation has come down, the same cannot be said for the money supply. Over the past few years, the government has consistently resorted to printing more money to bridge the fiscal deficit, which is the gap between its revenues and expenditures. This has increased the net domestic assets while foreign exchange reserves which are a part of Pakistan’s net foreign assets have not increased at a similar pace. Thus, increasing the pressure on rupee to dollar exchange parity.

As per data from SBP, outstanding open market operations (OMOs) at the end of February 29, 2024, stood at Rs 9.1 trillion, which is equivalent to around 28% of the total money supply.

OMOs are a key monetary policy tool that allows the central bank to control the liquidity in the banking system by either adding or removing funds through the purchase or sale of eligible securities, depending on the demand and supply of money. In simple terms, when the SBP injects money, it lends money to banks against some collateral. The banks then use this money to buy government securities. The SBP earns interest on the money it lends, while the banks make a profit by charging a higher interest rate to the government. For instance, if the SBP lends money to banks at 21%, the banks can lend this money to the government at 21.5% or 22%, earning a spread of 0.5% or 1%.

Injection of such large amounts of liquidity is one of the primary contributors to runaway inflation and has undermined SBP’s monetary policy efforts to control the price levels.

Read: Monetary Mayhem: Consequences of flushing the economy with money supply

“However, despite demand destruction at a household level, the government’s insatiable appetite for plugging its fiscal deficits through more debt continues to fuel more inflation. An elevated fiscal deficit eventually translates into higher inflation, as more money is printed to buy fewer goods available in the economy”, writes economist Ammar Khan in his article.

Khan argues that the country is still not out of the woods due to upsurge in global commodity prices with the price of crude oil and palm oil increasing by 12% and 8% respectively over the last one month. As Pakistan is an oil importer, this increase in commodity price could lead to pressure on the foreign exchange reserves.

So what will become of the rupee?

Analysts hold contrasting views on the future trajectory of the currency. “The rupee is expected to remain stable in the near term and could continue if Pakistan’s economy remains resilient. However, external factors such as fluctuations in oil prices or geopolitical tensions could influence the currency’s trajectory. Central bank interventions and monetary policies will also be critical in maintaining exchange rate stability. Therefore, the Pakistani rupee’s current stability is a positive sign,” says Saad Hanif, deputy head of research at Ismail Iqbal Securities speaking to Profit.

Conversely, any significant appreciation in the Pakistani rupee does not bode well for Pakistani exports, particularly those in the IT and textile sectors, which are important sources of dollar inflows for Pakistan.

Pakistan’s current account recorded a surplus of $128 million in February. Overall balance stands at a deficit of $1 billion during eight months of fiscal year 2024 against $3.85 billion in the same period of fiscal year 2023. As per Hanif, the current account deficit (CAD) position is being upheld by sluggish economic activity, leading to reduced imports.

However, analysts caution against a further deterioration in the current account position. Saad bin Naseer, director of Mettis Global, foresees a less optimistic outlook, projecting a deficit of less than $5-7 billion for the upcoming fiscal year. Similarly, Hanif warns of potential worsening of current account position if oil prices continue to rise in the near term.

Since Pakistan is an oil-importing country, an increase in oil price would result in higher import costs and hence put pressure on the rupee. “This can widen the current account deficit and reduce foreign exchange reserves. Consequently, this could lead to depreciation pressure on the rupee”, laments Hanif.

However, effective policies like stringent checks and reduced arbitrage between the open and interbank markets encourage robust remittance flows, offering a potential counterbalance to the CAD challenges

On a positive note, as per Hanif, the market has incorporated optimism regarding the new IMF program, alongside the country’s improving economic and political stability which will bode well for the foreign exchange market.

So what happens?

Amidst escalating inflation risks driven by surging commodity prices, energy price adjustments and a growing money supply, all economic signals converge on one outcome: an impending depreciation of the Pakistani rupee against the greenback. There is no appreciation in sight for the rupee. Unlike previous times, the central bank cannot risk depleting its already scarce foreign exchange reserves to maintain the exchange rate. The currency’s stability is contingent on the central bank using appropriate interventions and monetary policies to maintain exchange rate stability.

As mentioned earlier, globally central banks are being prudent. Hence, it is safe to say that SBP may also exercise caution in the upcoming monetary policy meeting. Finally, the last tranche of the existing $3 billion SBA, and the ability to enter a new IMF program might provide a much-needed breather to the reserves situation of the country and help strengthen the Pakistani rupee.