It is a dream that the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) and the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP) have been dreaming for a long time: getting more credit flowing to small and medium-sized businesses, the backbone of any economy, including that of Pakistan. And with the rise of fintech platforms, the dream feels tantalizingly close to reality.

The problem is that while technology can and does supply solutions to at least some of the bottlenecks that constrict the flow of credit to small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs), there would still be one that would trump them all: the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR), or more specifically, the approach of the federal government to setting tax policy.

Getting credit policy for SMEs – whether it be for a financial institution or a regulatory body – in any country not named the United States is incredibly difficult. And the State Bank in particular has been trying to balance the need to encourage this important avenue of credit while at the same time trying to manage the level of risk it would introduce to the banks’ balance sheets.

So what does it take to make it work? And is fintech really the key to helping unlock credit to SMEs in Pakistan? Possibly, but before diving into all of that, let us take a look at where things stand now.

The state of play

According to the World Bank, SMEs constitute around 90% of businesses globally, generating 40% of GDP and providing 50% of employment opportunities. Pakistan’s figures mirror these global trends, with 90% of business enterprises falling under the SME category, mostly operating in the informal economy. As of 2020, the country’s informal economy was estimated to account for 35%-56% of the official GDP.

The Small and Medium Enterprises Development Authority (SMEDA), using proxies like electricity connections for industrial, commercial, and agricultural sectors, estimates that there are currently 5.2 million SMEs operating in Pakistan. These SMEs contribute approximately 40% of Pakistan’s GDP, 30% of its exports, and employ around 78% of the non-agricultural labor force.

Despite the global consensus on SMEs forming the majority of private sector businesses, there is no universal definition for SMEs. Each country defines the segment using its own parameters such as number of employees, net revenue, output, investment, and value of total assets. The absence of a standardized definition has created dissonance among various government factions in Pakistan, with each department following its own definition, undermining the efficacy of initiatives launched for SMEs.

While departments like SECP, SMEDA, and SBP have agreed on a single definition (a company with a revenue of up to Rs800 million), there are dissenting voices. The Federal Board of Revenue (FBR), as per the Finance Act 2021, defines SMEs as companies with revenue of up to Rs250 million. They argue that extending the revenue limit to include a broader category of companies for preferential tax treatment would deteriorate the tax base and incentivize companies to underreport sales.

SME financing has been a major bottleneck in Pakistan for decades. Traditional banks have historically been apprehensive of lending to the private sector, preferring to invest in government-issued treasury bills. This inclination is fueled by multiple factors, primarily the high-risk profile of the private sector, particularly SMEs, further exacerbated by the high interest rates that have dominated since the beginning of fiscal year 2020.

Loans to private businesses have grown at a mere 7% annually, while banks’ investments in government securities have ballooned by 17.6% per annum. Consequently, loans to private sector businesses stand at only Rs7.1 trillion, while banks’ portfolio of government securities has exceeded Rs. 35.8 trillion.

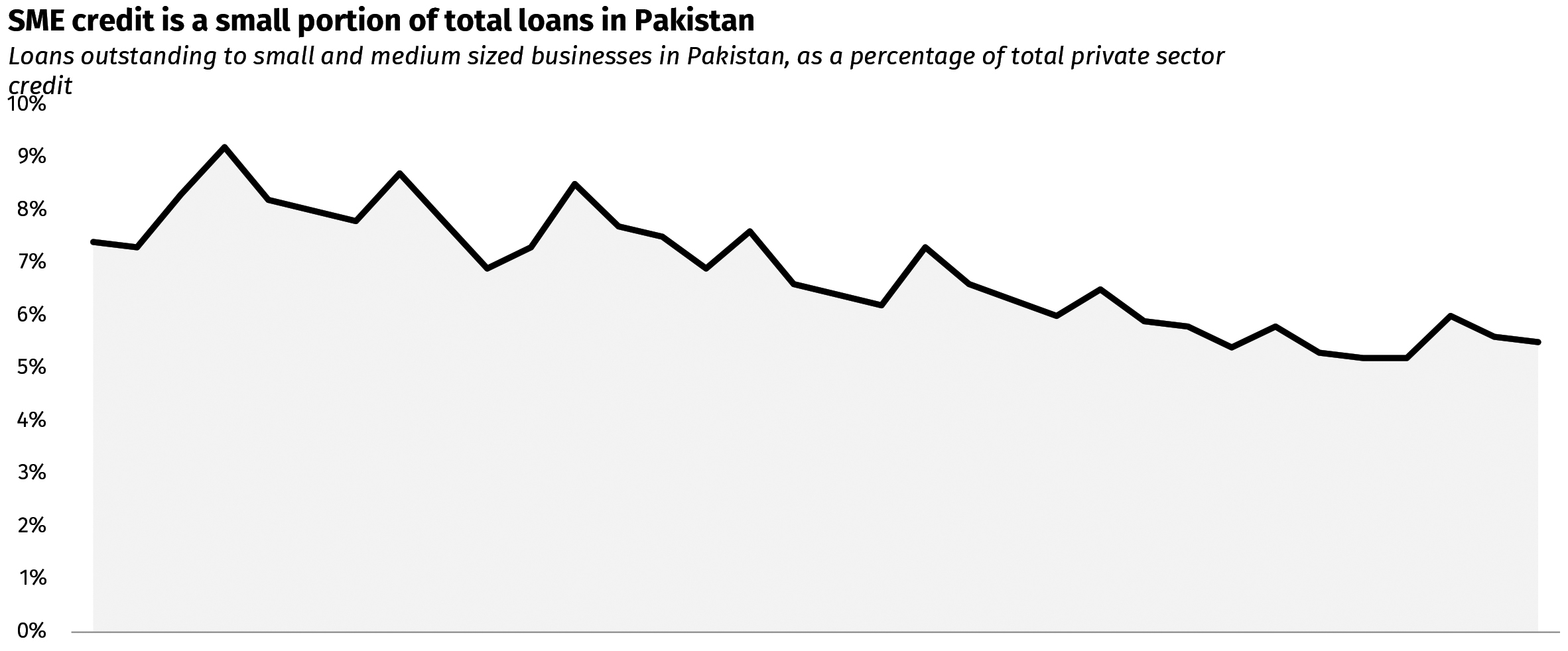

A closer look reveals an even more concerning picture: outstanding loans advanced by banks to SMEs stand at a paltry Rs572 billion, just 8.0% of total loans extended to private businesses, which itself is only 16.6% of the total credit. This means that SME lending constitutes only 1.3% of the total credit extended by banks in Pakistan.

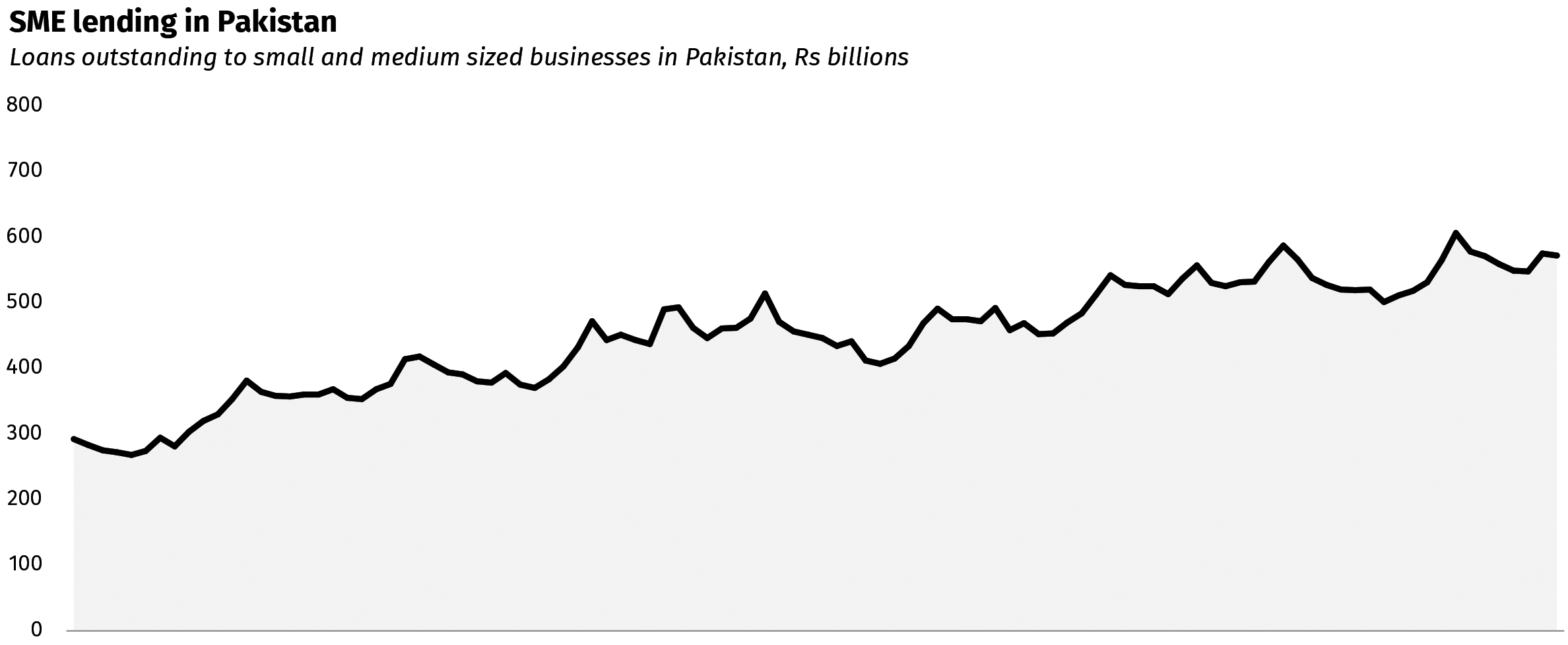

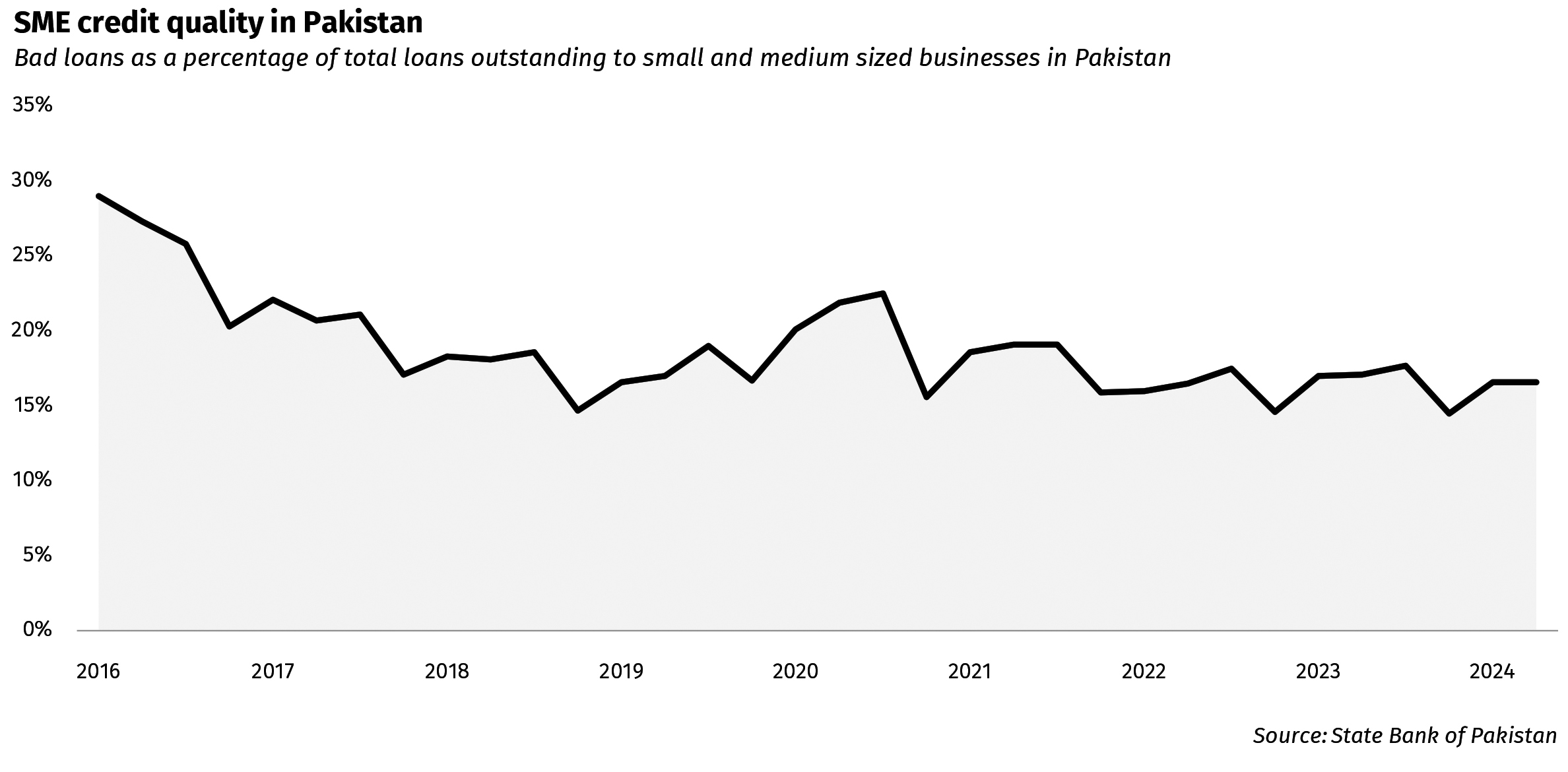

The growth in SME lending has been sluggish, with outstanding loans to SMEs increasing from Rs292 billion in December 2015 to Rs572 billion as of July 2024, representing an annual growth rate of just 8.1%. Moreover, the share of SME financing as a percentage of private credit has declined from 7.3% in June 2015 to 5.5% in June 2024, despite the Non-Performing Loans (NPL) ratio of the sector improving from 31.4% to 16.6% during the same period.

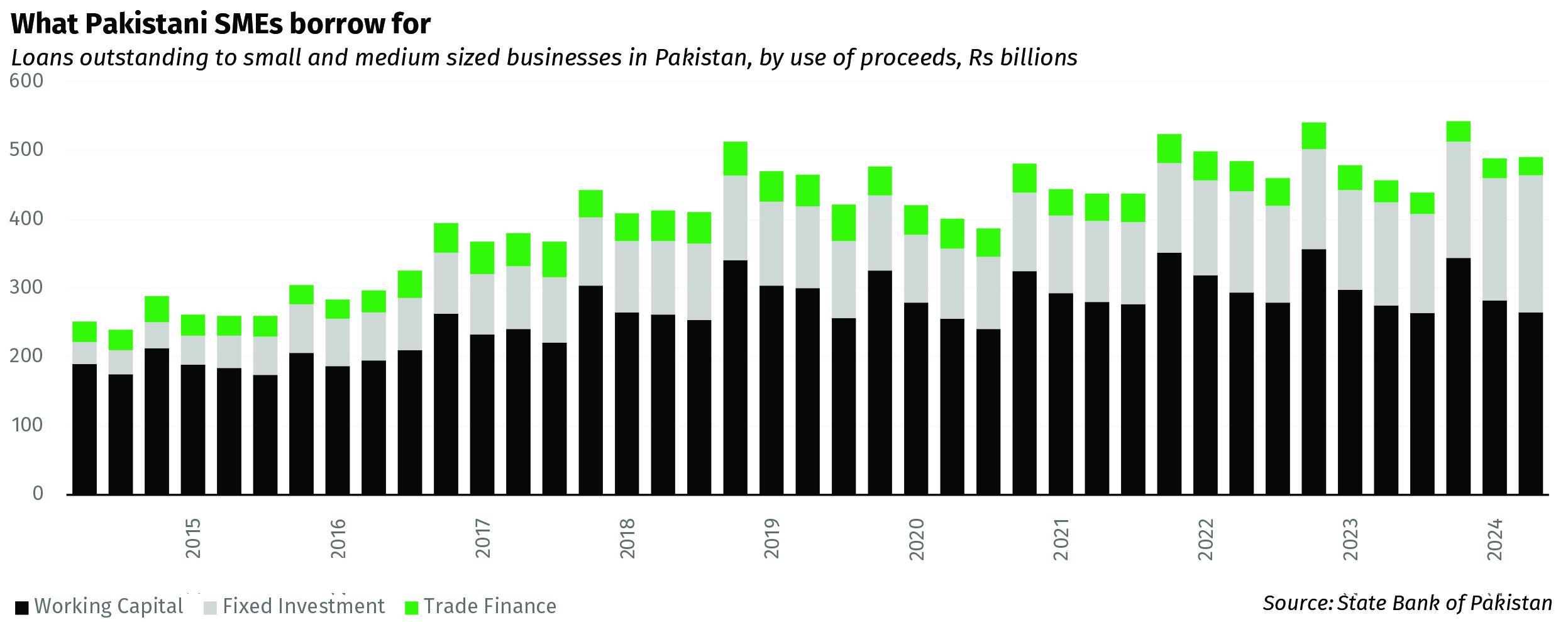

Analyzing the composition of credit extended to SMEs reveals that most of it (54.0%) is utilized for working capital requirements, while, 40.5% and 5.5% are used for trade finance and fixed investment, respectively, as of June 2024. These statistics underscore the significance of credit for working capital in the SME sector.

So why is the situation so bad? Because it is very, very hard to make SME lending work.

What it takes to make SME credit work

There are three main ingredients to helping make SME credit work:

- Low-cost deposits

- Low intermediation cost

- Visibility and predictability of SME cash flows

The low cost of deposits is necessary because it is very costly to deploy capital into small business lending, and so the cost of capital needs to be low in order to accommodate that high cost (both of disbursing the loan, and of the higher loan losses).

This point is worth explaining a bit: it costs a bank a lot more money to disburse smaller loans than it does to disburse a large loan. Consider the following, very simplified scenario.

Suppose Engro Corporation comes to Habib Bank and asks for a Rs10 billion loan. The bank’s average cost of deposits is around 10%, but it can lend to Engro at, for example, just 0.5% above the State Bank’s benchmark interest rate of 17.5% so it makes 18% interest on that loan. That represents an 8% per year net interest margin, or about Rs800 million per year.

To disburse the loan probably took about 20 highly paid corporate bankers and treasury staff the equivalent of perhaps one week of their time (averaged across all individuals), meaning even if one assumes an average salary of Rs1 million per employee per month, the operating cost of disbursing this loan to HBL, in terms of employee costs, was around Rs5 million (rounding a week to be one-quarter of a month). Let us be generous and add on another Rs5 million in overhead costs, and it still only cost about Rs10 million to disburse a loan that generates Rs800 million in net interest revenue.

Now let us add the the operating costs of the branches that HBL needs to maintain in order to even have that Rs10 billion to lend. In 2023, HBL spent about Rs29.6 million in operating costs on its branches per Rs1 billion in deposits, meaning the Rs10 billion in deposits came in at an operating cost of Rs296 million.

Let us add in all of these and you still get Just Rs306 million in costs for Rs800 million in revenue. The math is straightforward: relative to the size of the revenue from a large corporate loan, the cost of actual disbursement of that loan is not very high at all. And there is, of course, a near-certainty that Engro will pay that loan back.

Now consider the example of SME lending. What would it take to disburse Rs10 billion worth of loans to small businesses, assuming an average loan size of Rs10 million? Well, for one thing, that means giving out 1,000 loans. Let us assume you can charge significantly more interest – let’s say 25%. That would make the net interest margin on these loans about 15%, or Rs1.5 million per year.

Now subtract out the cost of the branch network, and you are left with Rs1.2 million in room to work with. Could you make a small business loan in that much? Maybe, but certainly not with the same caliber and compensation level of employees as the corporate bankers who made that loan to Engro.

So what would you need? You would need to essentially create an algorithm that decides who gets how much in loans so that even lower capacity employees are able to make decisions on whether or not to give the loan. But for that, you would have to assume that the financial statements being provided to you by the small businesses seeking the loans were reliable. And that they are likely to pay the loan back and that you will not have to spend yet more money chasing after them.

None of those assumptions, of course, is true.’

And herein we arrive at the problem of small business lending. It is not the margins that are the problem. It is the information asymmetry: banks have no reliable way of knowing who is a reliable credit risk and has both the capacity and intention of paying them back. If that is not possible, then the margins simply do not matter.

Could technology help?

The SBP has launched numerous initiatives over the years to boost SME financing, but their impact has been minimal.

Most SMEs in Pakistan transact in cash and resist adopting modern technology to evade government scrutiny. A common practice is the maintenance of dual books, one for official purposes and another for under-the-table transactions. While this helps SMEs minimize their tax obligations, it also presents a misleading picture to banks, making it difficult for them to assess the true financial health of these businesses.

Commercial banks, aware of these dubious practices, often disregard the account receivables and cash flow projections of SMEs, treating them as mere formalities. Instead, they resort to collateral-based lending, providing financing in exchange for valuables. However, SMEs frequently fail to present noteworthy collaterals, leaving them underfinanced for working capital.

The transition to clean lending, where no collateral is required and credit risk is evaluated based on cash flows, could potentially ameliorate the bleak situation of SME financing in Pakistan. While microfinance banks have had some success with clean lending, it is typically capped at low amounts, with larger loans still requiring collateral.

Some success stories in the microfinance sector offer hope. For instance, Mobilink Microfinance Bank (MMBL) has partnered with B2B marketplace startups to gain valuable data on retail merchants, enhancing its credit assessment models. Moreover, MMBL leverages various sources, such as Jazz GSM data, JazzCash account data, customer electronic credit information bureau details, and recharge on Jazz sims to further augment its credit assessment models.

Similarly, Telenor Microfinance Bank has launched initiatives like Easypaisa Karobar in collaboration with e-commerce infrastructure providers. Shahzad Khan, Head of Channels and Corporate Business at Telenor Microfinance Bank states, “Easypaisa Karobar is an innovative platform designed to help SMEs and MSMEs streamline their business operations and unlock new growth opportunities. By offering flexible stock financing and digital payment solutions, it addresses key cash flow challenges faced by businesses.”

And then there is potentially the most important one of all: the partnership of Haball – the B2B payments fintech – with Meezan Bank to help enable Digital Supply Chain Finance (DSCF).

By establishing a holistic digital ecosystem involving ERP systems and banking portals, banks can track transactions and goods exchanged throughout supply chain networks. This would enable them to amass historical data, making verification of identity, assigning credit scores, and estimating cash flows of SMEs more straightforward.

A representative from Meezan Bank Ltd. explains, “Digital Supply Chain Finance improves SMEs’ access to finance by streamlining the submission of onboarding and transaction requests through their ERP systems or other digital platforms. This seamless integration facilitates faster approval and disbursement of funds. Consequently, it lowers the costs associated with borrowing and simplifies the customer onboarding process, making financing more accessible and efficient for SMEs.”

DSCF could allow banks to intervene instantaneously in supply chain transactions, paying upfront to companies while allowing distributors to pay the bank at a later date, or paying vendors immediately while companies repay the bank later. Initially, banks are likely to follow an anchor-driven strategy, using large established companies as anchors and extending credit to associated SMEs based on verifiable transaction data.

Think about what each of the above examples are trying to do: use some means other than self-declared financial statements by small business owners to determine the actual financial health of those businesses, most specifically the volume and timing of their cash flows.

Why supply chain financing is attractive

It is an intriguing idea, and certainly one that might help reduce the intermediation cost and reliability of creditworthiness assessments for small business borrowers. If everyone connects their revenue and expenses to software tracking systems and those systems are accessible to banks, then the banks can make determinations about who to lend to and how much to lend to them almost automatically, with very little cost involved.

Add in the supply chain component, and it becomes even more attractive. To understand why, consider the following example.

We established earlier that the banks already have much more trust in larger Pakistani companies than smaller ones. What supply chain financing does is allow that trust to be leveraged for a much larger loan book than just the bigger company itself.

Consider, for example, a company like Atlas Honda, the motorcycle manufacturer. Atlas Honda is easily regarded as a low credit risk company by most banks. Now, imagine Atlas Honda wants to finance Rs10 billion worth of its cost of goods sold. It will borrow that money, and buy Rs10 billion worth of goods from its first level of suppliers. But that group of suppliers, in turn, has other suppliers that they rely on, and so on.

For simplicity’s sake, let us assume that there are four layers of suppliers, and that each layer operates on an identical 20% gross profit margin, meaning that their cost of goods sold is equal to 80% of their sales. Let us also assume that a bank – let’s say Bank Alfalah – lends not just to Atlas Honda, but all four layers of suppliers in that supply chain.

They lend Rs10 billion to Atlas Honda, Rs8 billion to the first layer of suppliers, Rs6.4 billion to the second layer, and Rs5.1 billion to the third layer. That is nearly Rs30 billion worth of loans. Atlas Honda’s loan paid off the first layer of suppliers’ loans, which then paid off the second layer, which then paid off the third layer. All Rs30 billion of loans got paid off a chain of the same sales made by Atlas Honda.

Even assuming a constant net interest margin (in reality, it would be different for each layer of suppliers) of approximately 8%, that means that the bank would earn Rs2.4 billion in revenue for a loan that functionally relied on Rs10 billion being paid back.

You can see why the banks and the SBP are excited about this prospect. This does not even require the suppliers to have formal accounts or even incorporation. All it needs to work is for them to agree to use a Bank Alfalah portal to track payments and a Bank Alfalah account to receive their payments so that the bank can deduct the loan amount from their revenues directly without having to rely on them to pay the bank back. One would have used technology to reduce the informational asymmetry without in any way changing the level of governance of the small business in question.

The problem, of course, is that this works great on paper but is much harder to implement in practice. Because in reality, each layer of suppliers gets divided up into progressively more and more companies, each of which has less and less formal documentation available to them at each stage, and not all of whom will even want to participate, even if the requirement for formal documentation is removed.

Why? Because small businesses in Pakistan are absolutely paranoid about becoming visible to the FBR.

The taxman problem

In other words, it is not enough to understand how to reduce the cost and reliability of information about the creditworthiness of small businesses. You have to go one level deeper and understand why the information is unreliable to begin with. And that reason is the FBR.

Nobody likes paying taxes, and Pakistanis are no more and no less inclined to pay them than any other country. What is true, however, is that taxation in Pakistan is unusually coercive in its nature, and it has to do with the incentive structure given to FBR officials.

The State Bank and the SECP have mandates for policy that go beyond governance. They are required to police bad behaviour, yes, but they are also required to promote growth in the industries that they regulate, which means that one can make the case for a policy by arguing that it will enable the industry to grow and that argument then at least gets taken seriously by both the SBP and the SECP. That does not work with the FBR.

The FBR is given only one goal: maximise revenue this year. Not even maximise revenue in general. Very specifically this year. If you are the chairman of the FBR, that is the only question the Finance Minister will ever put to you. He will accept any answer, even one that involves less revenue next year. Because next year is next year’s problem, and the politicians who run the country are concerned about surviving on a day-to-day basis.

And so the way the FBR goes about their job is trying to find out if the taxpayers about whom they already have a lot of information can be made to pay more. This means that registering a business with the FBR and being honest about how much money you make means attracting their attention when they get desperate about meeting their revenue goal.

This not just about inconvenience. The FBR’s policies sometimes amount to outright theft: they will collect “advance” taxes that are supposedly adjustable and refundable if you pay extra, but the refunds are never paid, so once you lose the money, it is gone forever, even if you were not legally obligated to pay that much in taxes.

Even if one company wants to become compliant with tax law and document everything, they will operate in a market where all, or nearly all, of their competitors are not doing so, and so this will put them at a massive competitive disadvantage.

So no small business ever wants to document itself and would rather accept the slower growth that comes from not having access to capital than to have their earnings stolen from them by the FBR and then lose their competitive advantage to rivals who continue to evade taxes. It would, quite simply, be irrational for them to start documenting themselves.

So the State Bank and SECP and all the fintechs can continue to develop all sorts of nifty products and regulations they want. None of it will matter until the FBR problem is dealt with.