If you are already the largest bank in Pakistan, do your financials really matter? Actually, yes. On February 24 of this year, the federal government-owned National Bank of Pakistan (NBP) reported massive earnings for the foregone year. The bank’s after-tax net income surged 84%, from Rs15.8 billion in 2019, to Rs30.5 billion in 2020. To put that in perspective, that is the highest net income that NBP reported in the last decade, by a long shot.

Here’s what the National Bank of Pakistan claims it is: it is the largest bank in Pakistan with Rs3.1 trillion in assets, it is the largest lender to agriculture with Rs225 billion disbursed to farmers, has the largest rural branch network with over 750 branches, and the bank was declared the best bank for agriculture in 2019. And to add to that, the bank has a customer portfolio of over 9 million customers.

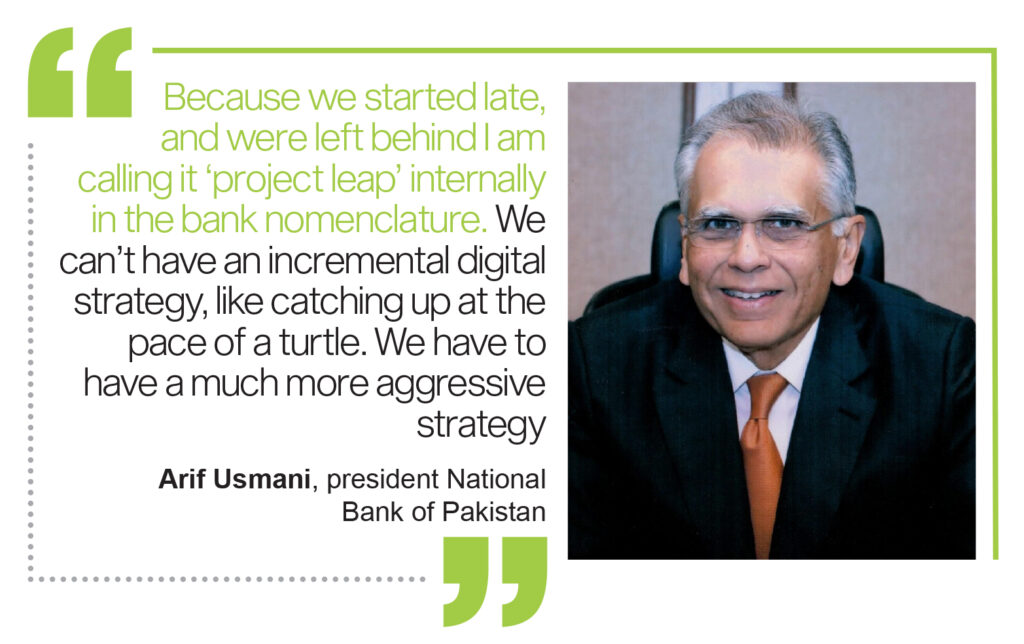

But despite all these distinctions, Arif Usmani believes that all’s not well at NBP. In a candid interview with Profit, he described a gargantuan bank suffering from severe disorganization, which was plodding along mostly though sheer luck.

And he is here to change that.

Who is Arif Usmani?

Before we talk about the bank’s strategy, let’s start with a little about the man himself and the bank he heads.

So first, the bank: the NBP was established in November 1949 under the National Bank of Pakistan Ordinance 1949, with an issued capital of Rs15 million. The government owned 25% of its issued share capital and the general public the remainder.

In 1974, NBP and all other banks in Pakistan were nationalised, in the general wave of nationalization that gripped the nation. Between 1995 and 2001, the assets, liabilities and operations of the former National Development Finance Corporation and Mehran Bank Limited were amalgamated with NBP, following a decision by the Government of Pakistan.

The bank was wholly owned by the Government of Pakistan until 2001, when the state sold a 10% stake to the general public through an IPO. Subsequently, the bank was listed on the Karachi Stock Exchange. In 2002, the government sold a further 10% stake in NBP to the general public. As of 2019, the Government of Pakistan retains a 75.6% stake in the bank. And in 2019, Usmani was appointed as the CEO of the bank.

Usmani belongs to the old guard of Pakistani bankers having started his career with Citi Pakistan in 1981 in the Corporate Banking Group, and since then held a number of positions with the company. With a career now spanning 40 years, the veteran banker served across several geographies and markets in various banking divisions, mostly in corporate banking.

From 1989 to 1994, while still part of the Citi Bank, he was on deputation from Citi with Saudi Arabia’s second largest bank SAMBA in Riyadh within the Corporate Banking business. 1994 onwards, Usmani relocated to the Asia Pacific region, where for five years he held a number of critical positions in different countries including Hong Kong and Singapore. Later, he moved as Citi Country Officer to Slovakia taking over as Country Head Citi Nigeria and Regional Head West Africa.

The latter role involved management of the Citi Franchises in Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon, Gabon, the Republic of Congo as well as Senegal.

Between November 2003 and August 2007, Usmani was the Chief Risk Officer of the Samba Financial Group in Saudi Arabia. Between January 2008 and March 2012, he served as the Managing Director of Citibank Pakistan. Then, between March 2012 and October 2013 he was the Global Head of Wholesale banking at Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank (ADIB). Between November 2017 and February 2019, he was the Chief Risk Officer at Mashreq Bank. Both ADIB and Mashreq Bank are based in the UAE.

Usmani dealt with his own minor controversy when he joined the bank: a Member of National Assembly (MNA) Ahsan Iqbal last year alleged that the NBP president, during his services in Nigeria, was involved in money laundering during his stint in Nigeria. The president categorically denied the claims, terming them ‘frivolous’, and even procured a letter from Citibank Nigeria, which said Usmani had not committed money laundering during his time as Managing Director.

But would it really be NBP if there was not some controversy or the other? As far as Usmani is concerned, the real scandal is the way the bank was being run.

A thorny inheritance

What’s the worst you can inherit at the bank?

“When I joined the bank, the issues were related fundamentally to the infrastructure of the bank, the core banking system and core banking application which had been acquired in 2005 and was implemented in 2013,” disclosed Usmani in an interview with Profit.

It was a view he had reiterated earlier last year, at the Digital Banking and Mobile Payments Summit 2020. Usmani had expressed frustration at the bank’s digital efforts:“We look at the digital piece where we are behind the curve. Private commercial banks have invested heavily to move the needle forward. National Bank has not. I see this as an opportunity to catch up and leapfrog the competition. We have a very wide reach of customers and we can significantly change their experience and journey with a few buzzwords at National Bank.”

He had further reiterated: “Today our customers have to deal with National Bank, and if we want to change from ‘have to deal with’ to ‘want to deal with’ National Bank, this technology transformation both internal in our infrastructure and external as we touch the customer has to change.”

“We have a long way to go and we have historically been a branch centric, physical infrastructure bank which is no longer relevant. And how we reach our customers by opening branches in rural areas etc may still be relevant but it is getting less relevant. People can access the branch remotely on the phone and all that is happening. We have obviously not gotten there yet. And the more we see happening in this space, the less National Bank feels comfortable with its preeminent position as the government’s payment bank. I think we could become irrelevant if we don’t fix our game in this space.”

Historical financials

So, how well has the bank done in the last decade? Let’s take a look.

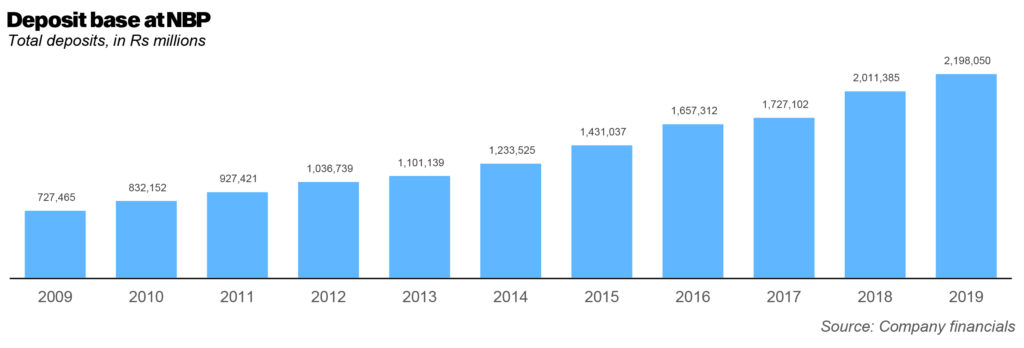

First up, the bank’s deposits have been steadily increasing since 2009, when deposits stood at Rs 727 billion. In particular, deposits grew 16% year-on-year in 2015, and at 16.5% year-on-year in 2018. Deposits crossed the Rs1,000 billion mark in 20123, and the Rs1,500 billion mark in 2015, and finally, crossed the Rs2,000 billion mark in 2018.

If one looks at the deposits as a share of the total deposits in the banking industry, NBP has always commanded around roughly the same share. The bank’s highest market share in this period was in 2009, at 16.8%; this fell to 14% in 2017, the lowest it has been in this period. However, market share has climbed back to 15% in both 2018 and 2019.

And, if one one looks at the compounded annual growth rate for deposits for the five year period between 2014 and 2019, NB has done well: the rate is 12.25%, which is higher than the industry average for the same period, at 11.89%.

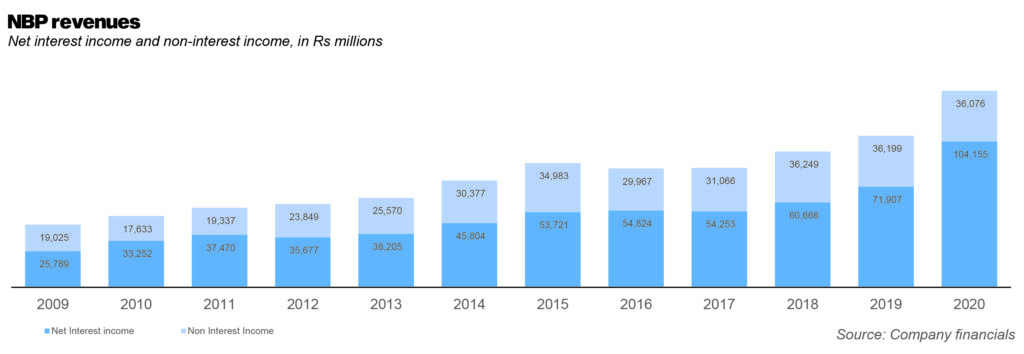

NBP’s revenue during this period has been on a steady upward trajectory, from Rs44.8 billion in 2009, to Rs140 billion in 2020. Most of this is driven by net interest income, which stayed in the Rs50-60 billion ballpark between 2015 and 2018, before drastically jumping to Rs72 billion in 2019, and then Rs104 billion the year after. Non interest income shot to Rs35 billion in 2015, fell somewhat in the years after, and then was maintained at Rs36 billion for the period 2018-2020.

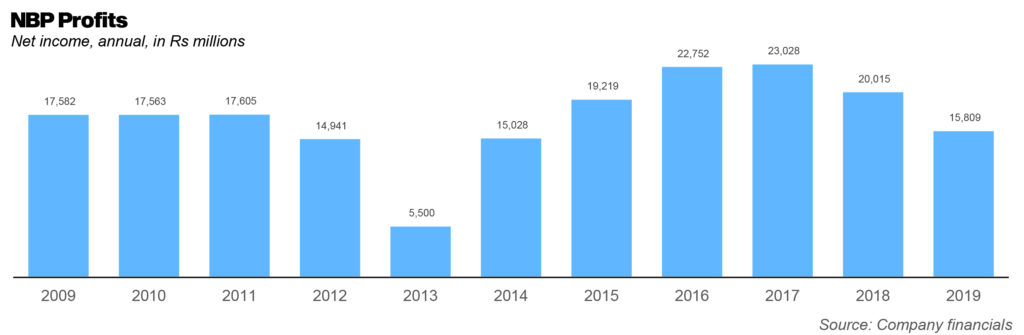

While revenue has been somewhat stable, the same cannot be said about net income trajectory. Between 2009 and 2011, net income hovered in the Rs17 billion range. It then drastically fell to Rs5 billion in 2013, a particularly poor year. It then crossed the Rs20 billion mark in 2016, where it hovered until falling to Rs15.8 billion in 2019 (a poor year), and then climbed to Rs30.5 billion in 2020 (its best year so far).

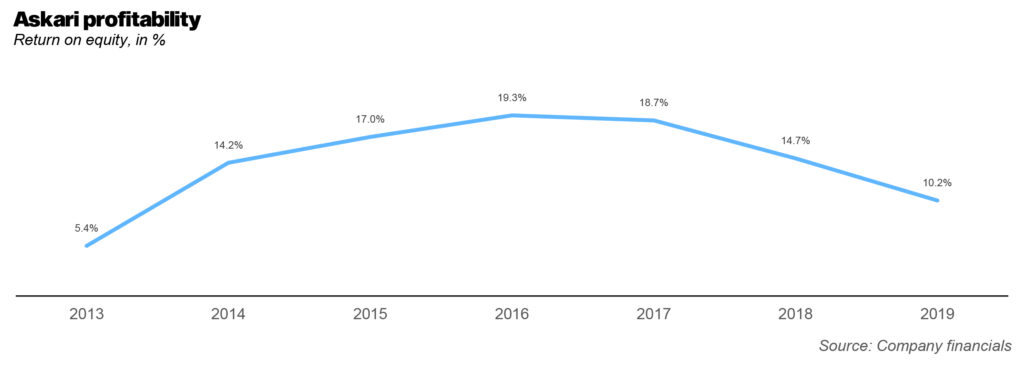

From the information available in some annual reports, NBP has had varying return on equity (ROE) which is an indication of financial health (basically, how effectively management is using a company’s assets to create profits). The bank’s ROE stood at 5.4% in 2013, jumped to 19.3% in 2016, before falling to 10.2% in 2019.

So what explains the meteoric comeback of this year? As mentioned before, the earnings of NBP surged 84% to Rs30.58 billion during the year ended December 31, 2020. Against a 28.95% growth in total income, the bank saw a 4.36% decline in total expenses, which further helped boost its earnings. The interest income increased by 7.64%, with decline in interest expense by 8.3%. Thus, the net interest income of NBP grew by 44.66%. However, the non-interest income didn’t show the same momentum as it fell by 1.06% on account of lower fee income, dividend income, forex income as well as non-core income.Still, the sheer size of the interest income more than made up for it. It is worth mentioning that NBP saw a 265% growth in securities. However, some setbacks were faced in the form of a 128% increase in provisioning costs, as well as a 28.12% rise in income tax expense.

Non-performing loans

If one were to just look at the historical numbers above, and the excellent year that was 2020, one would think that the bank has few concerns.

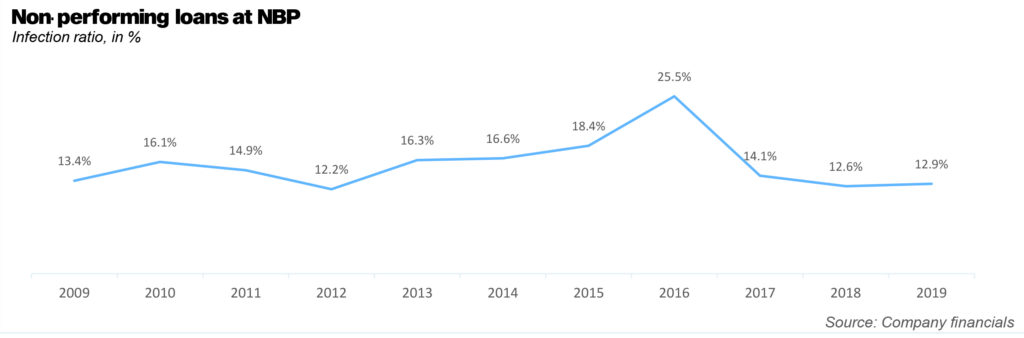

But perhaps the biggest problem area for the bank has been, and continues to be, the share of non-performing loans the bank has. In the last decade, there has been exactly one year where the bank’s infection raito was lower than the industry average – almost every other year the bank’s infection ratio has been higher. The greatest discrepancies have actually been seen in just the last few years: in 2015, the infection ratio was 18.4% compared to the industry’s 11.4%; in 2016, 25.5% compared to the industry’s 10.1%; in 2017, 14.1% compared to the industry’s 8.4%; and in 2018, 12.6% compared to the industries 8%.

This is deeply concerning, and Usmani is aware of it. In conversation with Profit, he admitted that the NBP of the past had been forced to give out political loans. But that has changed.

“I am very happy to report that I have had zero pressure from the government in the last two years to give any loans. So we don’t really have new loans of political pressure now, there are old ones. There is legacy but not flow, which is great for NBP.” he said.

He added: “And frauds are real, banks have to live through frauds because of the inherent nature of the business. Sometimes it happens at the branches, sometimes with fake signatures, sometimes errors and omissions. So operational risk is there, we have to minimise that.”

Lessons in restructuring

There were a few things Usmani did when he joined the bank. Within the commercial and retail banking group, the SMEs, agriculture and commercial segments were all amalgamated. Usmani’s first task was to disentangle the segments, in what he described as a ‘major and painful surgery’ at NBP. One group was made into a pure retail and consumer bank, and the other was the SME, agriculture and commercial activity, which was then further subdivided into three.

The effect of this was to realize exactly how small the agriculture division is. Of course, one would not know this based on the figures available. NBP gave out Rs61 billion in agriculture loans in 2020; the bank has set a target for Rs66 billion for 2021. It serves over 260,00 small farmers, and even when the ‘Best Bank in Agriculture’ award recently.

Usmani was not impressed, however. “The reason we got the ‘Best Bank in Agriculture’ is that we have 260,000 farming clients. There are 9 million farmers. What is 260,000? We should be at a million.We are at 260,000 right now, which is not even 25% of what we should be doing.”

“In my room, I have a map that outlines Pakistan’s GDP and interactions of NBP in the various segments of the GDP. In that map, our interaction appears very small in agriculture. So when I disentangled SME and agri business, the purpose was to highlight how small we are in agriculture. And the purpose of carving out a group is so that we can become the biggest group.”

Usmani also created a separate division for the government of Pakistan and specialised agencies, which had also been subsumed into retail banking. Agencies like Pakistan Atomic Energy, and the Controller of Military Accounts, were now being treated as retail clients.

Usmani said, “I corporatised it, and now they see the difference. We call on them regularly, we solve their problems. We have corporate finance, investment banking people looking at railways, their financial needs. Their collection of cash, their trade finance, all of this we have professionalised. This is one of my lasting changes, I hope it lasts longer than I last at NBP. This is a fundamental change, everywhere I go in Islamabad, the government of Pakistan and the specialised agencies division, I get real pleasing remarks from our customers saying that now we see National Bank, as a proactive, full relationship management. Because a retail bank is an amorphous relationship with 8 million people. You can not run it as a corporate relationship bank as it is supposed to be run. And we were running all three businesses as a hotchpotch.”

This approach is not with its fair share of detractors: “The people, old ones in retail banking, said that Usmani Sb has brought it into corporate. The fact is that it comes in corporate. You were managing it wrong from the last 70 years.”

As an example, he brought up an anecdote: “ I had a dinner with the entire [Pakistan] railways team the day before yesterday, nobody has ever invited them to anywhere to talk to them, and discuss their trade finance requirements, their new railway line that is from Lando Kotal to Karachi is being laid with Chinese help, how is it going to be financed. National Bank was [previously] just a collection bank for them. They had accounts at 260 stations. Now that is a change at National Bank.”

The future

So what is next for the bank? First NBP will sort out its digital strategy. Usmani is in the process of selecting a digital financial officer, a position which has now been changed to directly report to the president. Usmani also realized that NBP’s technology infrastructure was weak, so created the technology and digitalisation department, designed to tackle hardware problems.

“Because we started late, and were left behind I am calling it ‘project leap’ internally in the bank nomenclature. We can’t have an incremental digital strategy, like catching up at the pace of a turtle. We have to have a much more aggressive strategy.”

Despite the recent corporatization and restructuring, Usmani is aware of the mandate of the bank: “NBP fundamentally is a rural bank. Our rural distribution is higher than other banks. Habib Bank has more branches,but we have more branches in unbanked and rural areas. If you read our vision statement, it is now around development and sustainable and inclusive development. We have tried to change this bank from just being a larger version of other commercial banks to a more focused on outreach and development and sustainability environment as a national bank should be.”

Usmani has laid the groundwork for a transformation. If the bank can get a handle on non-performing loans, and rework its digital infrastructure, perhaps the bank will go from ‘have to deal with’ to ‘want to deal with’ after all.

A seasoned banker who is an asset to Pakistan’s banking sector. Hopefully he will bring the changes he is aiming for before he is removed like other sincere individuals, who have tried to do some good to the country but were forced out by the corrupt.

Its unreal and kind of surreal at the same time, to read of NBP’s financial structure and gains… the iron curtain that draped its Operational and Financial make-up is being cautiously removed.. analysed and attended..

Kudos, Mr.Usmani.. but watch out for those tidal undercurrents; the cultural challange that you inherit, is more toxic, than it appears.

Albeit late, the Giant awakens.