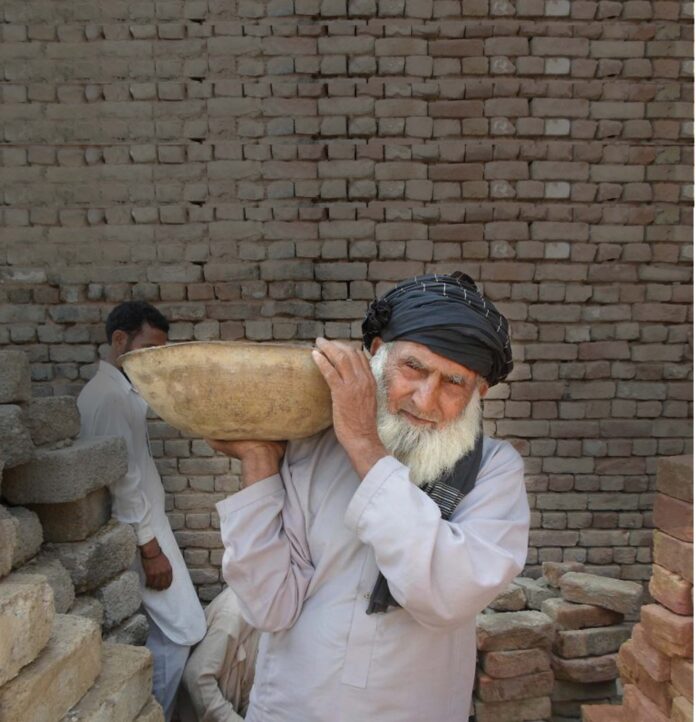

What does the life of a daily wage worker at a seth sahib’s factory look like in Pakistan? Let’s be blunt – if you’re privileged enough to be reading this magazine, you probably have no idea.

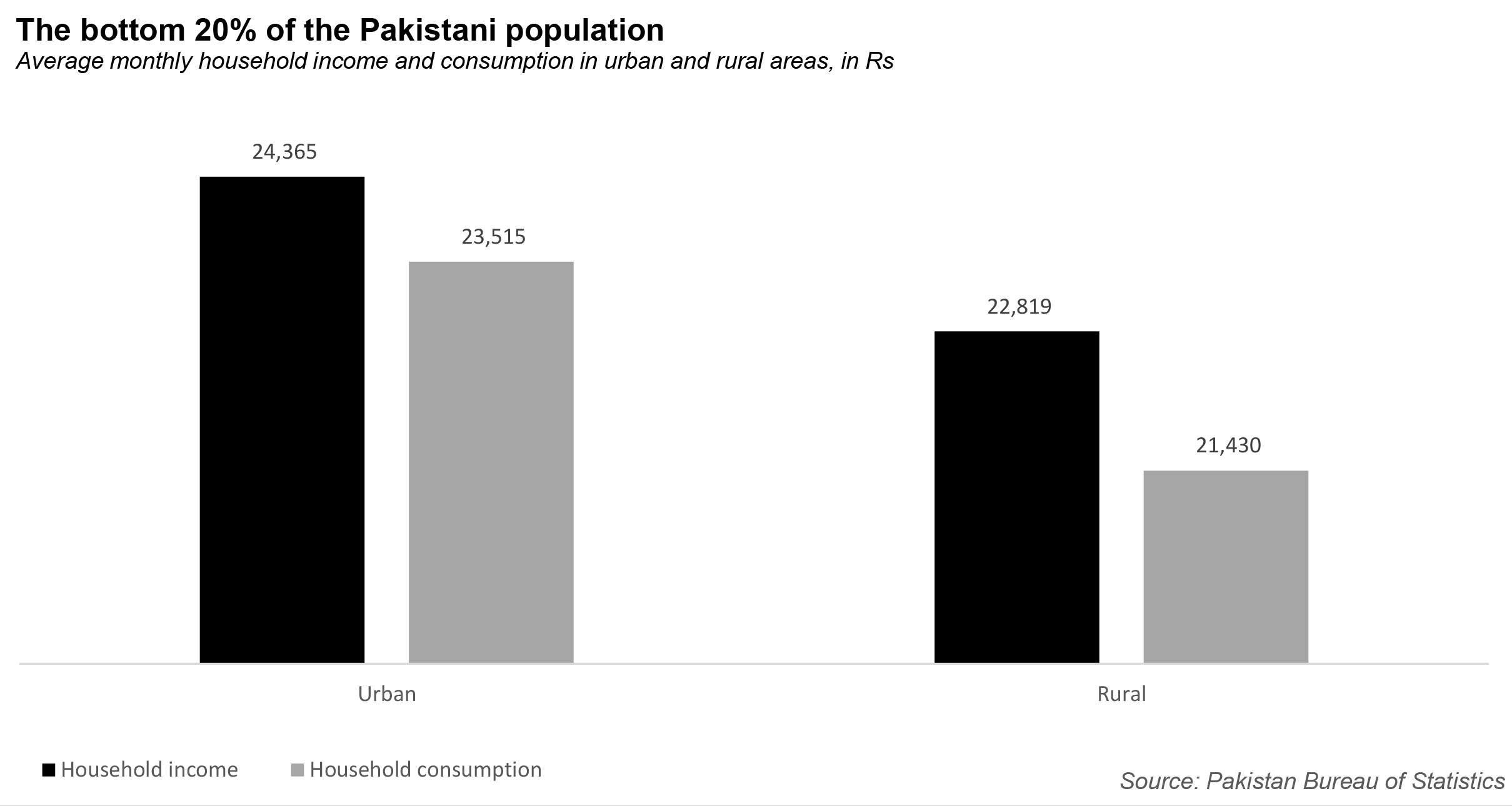

Thankfully, here’s where the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics comes in handy. According to Household Integrated Economic Survey 2018-19 data, the bottom 20% of the Pakistani population in urban centres earns Rs24,365 per household per month, and consumes Rs23,515. In rural areas, the average income per household drops to Rs22,819 per month, while monthly consumption is Rs21,430.

Most of that monthly ‘consumption’ is spent towards rent, food, and utilities. As you can imagine, this does not leave much money left over for miscellaneous items. And considering that inflation has averaged at 9% in the last 12 months, savings are a distant dream.

So, what happens if the daily wage worker has an important financial expense to make, say a child’s education, or a child’s marriage? Who will fit the bill?

Easy: either a previously set up committee, or (more likely) a local lender in the community who gives out loans for immediate use.

Now the conventional thinking is this: that these lenders are B-A-D. In the minds of policy makers and bankers, predatory lenders and loan sharks charge horrendous amounts of money to the financially vulnerable members of the society for financing their needs. Think, for instance, of the farmer who is exploited by the middlemen who buy his crop at their whims at arbitrary prices.

If only we had more financial inclusion, say the perfectly well-meaning policy-makers and bureaucrats. If only low-income households have access to the formal financial system, they are able to better finance their needs, without establishing exploitative relationships with players in the informal sector that eventually adds to their poverty. If only more low-income Pakistanis opened a bank account, and took loans from the formal sector, be that banks or mobile wallets.

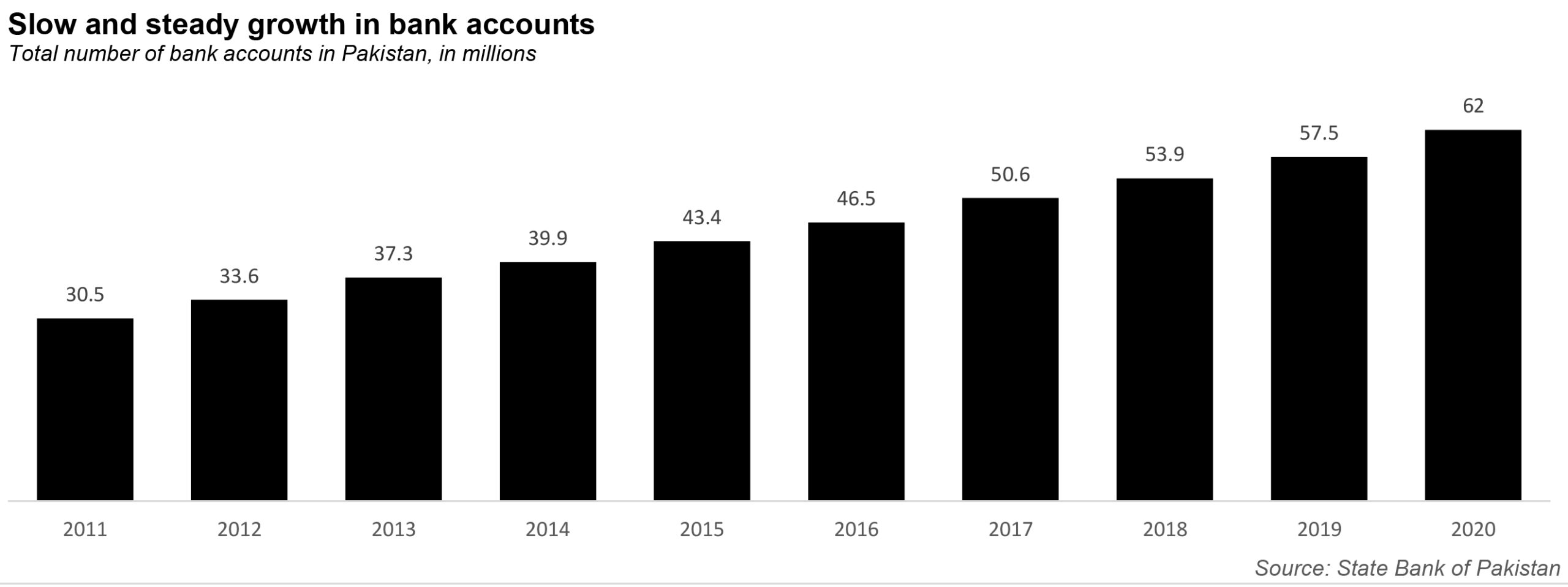

Now, to be clear, financial inclusion is a massive problem. According to the numbers from the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) for June 2019, the numbers of bank accounts were 57.7 million in a population of 220 million. That is a little over a quarter of the Pakistani population is banked. A new dataset from the SBP puts the number of unique bank accounts at 66 million for the year 2020. Encouraging? Yes! But the growth in bank accounts might simply be pandemic induced, fueled by need and is still only slightly above a quarter of the population. The same dataset puts the percentage of accounts that are active at 60%.

Another dataset from World Bank’s Findex Database puts the percentage of the adult population that is banked at 21% for 2017. That is already a dreadfully low number of bank accounts if you compare with regional peers. India, for instance, has 80% of its population that is banked.

When the central bank announced its National Financial Inclusion Strategy (NFIS), less than a quarter of the population was banked. Five years on, it’s still only a quarter or a little more that is banked. And According to SBP’s Access to Finance Survey 2015, only 7% of the adult women in Pakistan were banked.

So clearly, there’s a problem. And well-meaning policy makers are trying to change this. But why are low-income so resistant to opening a bank account, or taking a loan from a bank?

It helps if one steps and stops thinking about a government and its obligations to citizens. Instead, think of a company. Ultimately, companies flourish when they design the end-consumer in mind. They fail, when they keep thinking they know better, and stop asking what the hurdles are for the consumer, or what they even want.

And so it shows here. Let’s consider that so-called bad ‘loan shark’ that operates in the informal economy, which proponents of financial inclusion believe rip customers off. In an example shared with Profit, a farmer from a village in South Punjab took out a Rs48,000 loan for his marriage for six months, and paid back Rs62,000, translating to an interest of 25% paid for a six-month period. In another example, a lender from the same village charged 30% interest for the amount that he lends.

But here’s the kicker: in the same district where the village is located, the National Rural Support Bank (NRSP) Bank charges a whopping 39% on personal loans.

Which do you think the end-user is going to use? Do you think he cares about government year-end goals for financial inclusion, or will bother trying to set up a bank account, a process that will take weeks? No, he will go to the lender. In this narrative, it is the formal channels that are the predatory loan sharks.

Between the three, the mobile wallet, the bank and the private lender, a low-income person who does not have a formal bank account is likely going to take out a loan from a private lender other than banks or wallets because these loans are easy to get; no need of formal paperwork or processing times or the prerequisite usage of wallet or telco services. The interest rate is also less than what the banks charge.

From the perspective of the low-income household, financial inclusion is overrated, because the services offered, and the hassle of engaging with the formal sector are simply too much. The government, and the banks in Pakistan have not figured out how to improve their systems. In this article, we will point out the two separate options available to a customer – mobile wallets and banks – and then look at how easy it is to set up an account.

Option 1: the mobile wallets

The story of how EasyPaisa started also reflects the need for a bank account for everybody in Pakistan. Back in 2008-9 when EasyPaisa was launched, people working in cities did not have any options to send money back home. If the hometown was close to the city, the earning member would visit family members frequently and give the money back home when he would visit. If the distance would be longer, he’d have it delivered back home by paying some bus driver to do it for him. Alternatively, he’d give the money to some acquaintance or some extended family member visiting the city and request them to deliver the money if they were also to travel back at the same time. All in all, it was a pretty shaky and not very safe system.

In the above arrangements, the transfer of money back home would only happen if the earning member himself or any of his friends or family members visited. The practice still goes on today. Low-income groups try to save expenses by requesting friends or acquaintances to carry money along with them if they are travelling back home at the same time. Alternatively, they could deliver money via buses, but this can be time-consuming, carries a charge and may still carry the risk of fraud.

In 2008, the State Bank of Pakistan introduced Branchless Banking regulations that would enable EasyPaisa and JazzCash to have a network of agents that would act as a bank, without the presence of a physical branch, to carry out financial transactions like transferring of money from one place to another. They would do the same thing that the bus driver or conductor does, except that this transaction would now be almost instant and less expensive. Be it bank accounts or wallets, the movement of money through these formal channels would help keep track of and document transactions. In turn, it would also helps curb the use of cash.

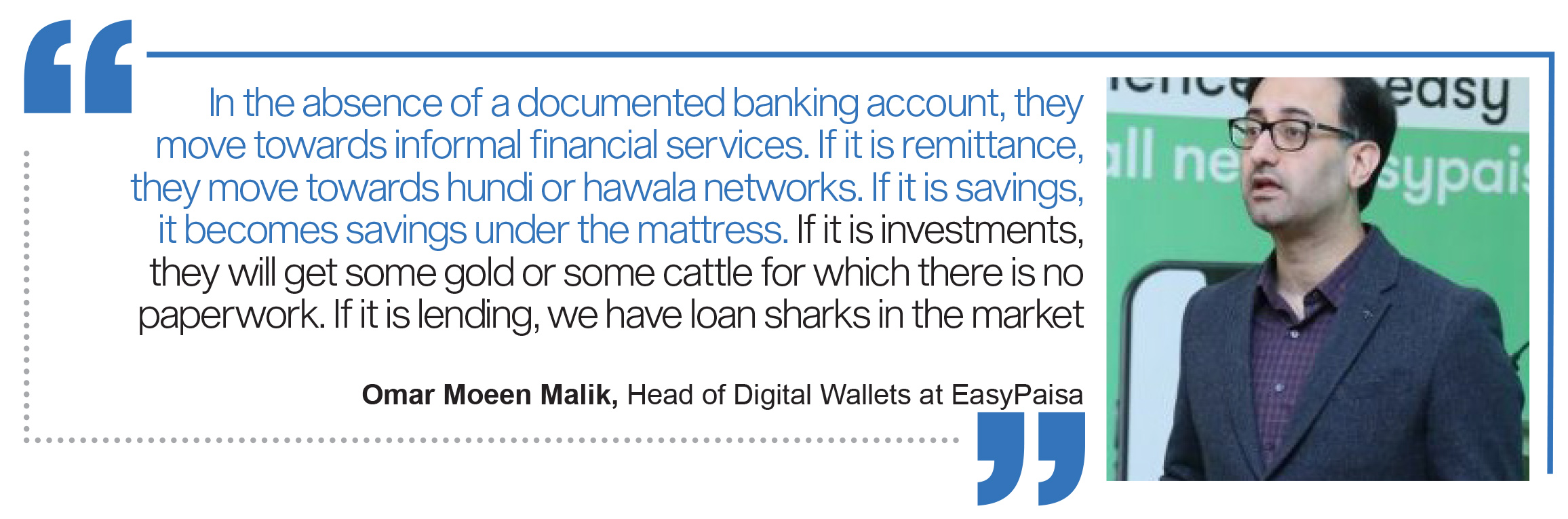

Easy Paisa clearly sees itself as a solution to the problem. As Omar Moeen Malik, Head of Digital Wallets at EasyPaisa said,“In the absence of a documented banking account, they move towards informal financial services. If it is remittance, they move towards hundi or hawala networks. If it is savings, it becomes savings under the mattress. If it is investments, they will get some gold or some cattle for which there is no paperwork. If it is lending, we have loan sharks in the market,” he adds.

Services like Easy Paisa aim to correct this narrative. So, for instance, another reason why mobile wallets are attractive is because they offer credit on demand and guarantee almost instant access to loans of Rs 10,000.

However, this is not as smooth as it seems. To access these loans, first you must have a sim of Jazz or Telenor, the telcos behind EasyPaisa and JazzCash, and must already have a wallet with them. The company then decides how eligible you are for the loan depending on your usage of the telco services and wallet. Because of all these caveats, most people still prefer going to the much simpler but much more deadly loan sharks.

Where it gets more difficult is that the loan, that can be given out at a maximum limit of Rs10,000, has to be repaid in a month at a 5% of the total loan charged in fees each week for the credit service. So if you took out a Rs10,000 loan on EasyPaisa, you’d be paying back Rs12,000 at the end of the month, translating in a 20% rate for a month, or 240% for a year, if you were to take out the same amount of loan each month for a year. If the outstanding loan amount is not repaid within a month, the deadline is extended on a weekly basis for another four weeks. Failure to repay even after the extension of the deadline would result in the wallet blacklisting you and cancelling your eligibility for future loans.

Option 2: the bank

Would Rs10,000 be sufficient for someone, who, let’s say, has to take out a loan to get one of his children married? Who can they turn to? Well, the banks.

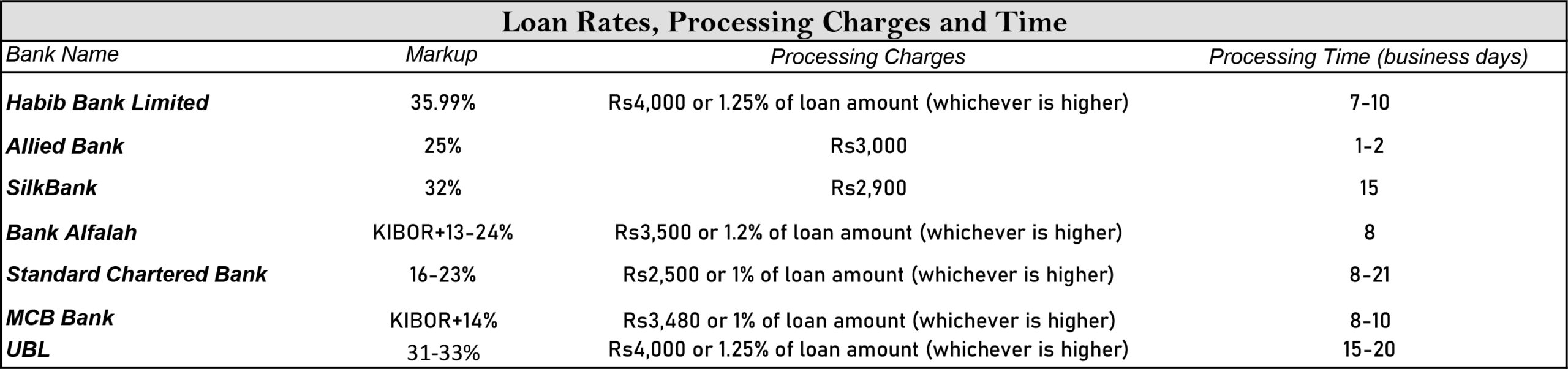

The loans from the banks are actually more costly. This reporter’s own bank that was called to learn about charges associated with taking out a personal loan told us that for a loan of Rs50,000, the minimum limit of a personal loan, can cost as much as KIBOR plus 24%. The 1-year KIBOR rate nowadays is almost 8% which means that the loan would be charged at 32% for a year. The bank further charges a few thousand rupees, Rs3,500 in the case of the reporter’s bank, as the processing fee for the loan and the loan takes a few days to process.

“The interest rates at banks and even microfinance banks are high. In the case of microfinance banks, they try to justify high interest rates by saying that they have high operational expenses. While they are borrowing these loans from commercial banks at roughly 10% interest,” says Ali Sarfaraz, CEO of Karandaaz Pakistan, an online data portal with aggregated data on financial services and selected socioeconomic indicators for the country. It is a non-profit organisation that aims to bank the unbanked population and provide access to finance to small and medium sized businesses.

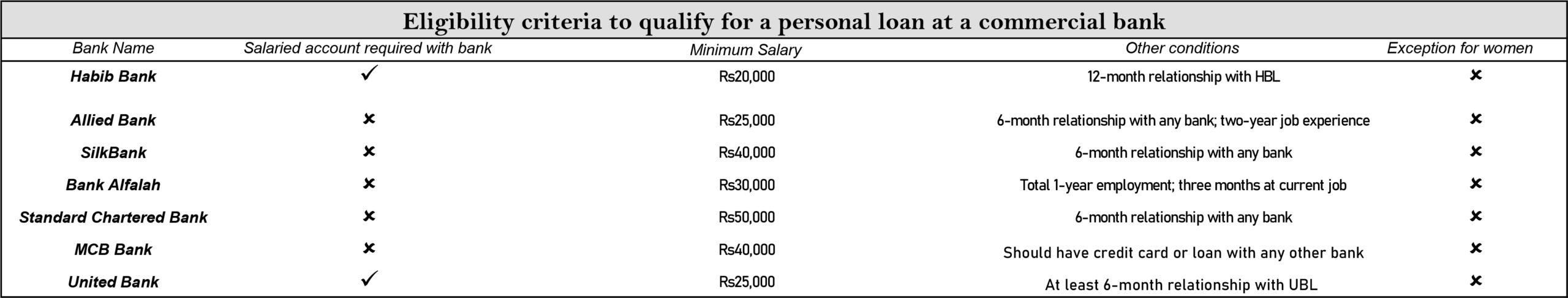

It is startling that Pakistan’s top bank, Habib Bank Limited (HBL), does not offer personal loans at all, unless you are working with a company that has an account with HBL and your salary is deposited directly into the account that your company opened for you with Habib Bank (Editor’s Note: That might soon change, if HBL ends up acquiring the consumer lending portfolio of Silkbank). This is despite having a designated chief financial inclusion officer in HBL’s management.

Profit reached out to HBL for comments about the role of the chief financial inclusion officer at the bank and measures taken by him to promote financial inclusion. No response was received till the filing of this report.

Of the remaining banks surveyed by Profit, it looked enormously difficult to get a loan for the unbanked, unless, ironically, one was part of the formal sector already. Most banks require a prior relationship of a few months to a year with any bank to be eligible for a personal loan. Most of them also further required to furnish bank statements if one had an account with any other bank, and salary slips.

The question here is this: can a daily wage labourer or a driver working at someone’s house in urban Lahore provide salary slips or bank statements to apply for a loan at a bank? “No!” is the most likely answer. Some banks even have minimum salary requirements of Rs50,000 for someone to be eligible to get a bank loan.

Financial inclusion proponents point out that private lenders have no uniform charges; but there is also no uniformity of charges when it comes to commercial banks. All the banks have their own set of offerings, with arbitrary rates. In-principle, both are the same: predatory.

How does one open a bank account, anyway?

High-charges that discourage customers from seeking loans are sometimes the least of a customer’s problem. Just opening and maintaining a bank account has remained an expensive task for low-income earner with the requirements of large deposits and minimum balance requirements that run in thousands of rupees. Therefore, the thinking with the policymakers at the SBP has been that if banks could be easily opened, financial inclusion would increase. Therefore, the policy has remained at the ease of opening bank accounts.

The SBP has introduced low-tier accounts. For such users all the costs are absorbed by the banks. Take, for example, the Aasan Account.

Remember that access to a bank account is what should open up avenues for other financial services like personal loans. That is the whole concept of financial inclusion. But even the opening of accounts has remained lacklustre despite the fact that the SBP has mandated accounts that do not even cost much to open and maintain.

The Asaan Account is a type of current account that is targeted at common people and is open to all low-income unbanked and under-banked masses who face difficulties in account opening due to normal account opening requirements or lesser means. But as it turns out, opening an Asaan Account remains arduous.

Profit surveyed four banks and one thing was abundantly clear: not enough is told to prospective customers about the benefits that come with a bank account that they pitch. Neither do they tell customers what they will not get with the account that they are pitching to the customer. What is certainly there is the complicated set of documents like judicial stamp papers from the employer that a person has to submit to prove that he has a job.

What is more ironic, however, is that with an Asaan Account, people do not get access to financial services that the central bank apparently wants them to get access to. Take personal loans again. The bank representatives at three banks categorically said that no personal loans or credit cards are offered to Asaan Account customers because of their low-income profile. The fourth bank was not offering personal loans at all. All they get is a debit card and a thin cheque book, all paid for by customers.

And this does not end here. Bank charges for services like fund transfers to other accounts are high that can possibly create deterrence for consumers to use bank services. Take Interbank fund transfers, for example. Interbank fund transfers from a branch can cost you as much as Rs500 for a single transfer regardless of the amount that is sent. It would be the same for sending Rs2,000 or Rs20,000. In case of interbank fund transfer using internet or mobile banking features of a particular bank can also be costly, with a single transfer costing Rs150.

What is appalling, however, is that interbank fund transfers are enabled by 1Link that acts as a switch to make IBFTs possible. However, for IBFTs, 1Link only charges 1 rupee to banks for each transfer. Whatever the banks earn on top are discretionary and predatory charges, as in the case of debit cards. Another example are credit cards. Part of the reason why credit cards have been unable to take-off in Pakistan are high interest rates charged by banks on credit cards.

“Direct charges by the banks are very high and they deter customers from using banks’ services,” explains Sayem Ali, a banker and an expert in finance. “Banking is expensive globally and it is expensive in Pakistan. Banks think that the charges are justified against the services they provide to customers,” he adds.

Wallets, on the other hand, have been able to do well. They have actually been a hit among the low-income segments of the population but their usage has been limited mostly to the transfer of money through branchless banking agents. So what does someone who earns a small amount of money get by opening a bank account? One can argue that safety and security of money is what a bank account brings. Not really!

Scams at banks are real and people have been defrauded of their money by scammers. The low-income category of population, that is mostly illiterate, is more prone to such scams. Skimming frauds are also not uncommon and thefts at ATMs are also a normal occurrence. All these instances mean that money in the bank is not as safe and secure as it is considered. So why should a low-income person pay for a bank’s services when he can still be defrauded and still can not access services like personal loans etc.? And because of low literacy rates, among the unbanked, knowledge of how to make transactions through ATMs or even writing cheques is challenging.

The case of unused accounts

Even for the population that is banked, it has been reported that there is little usage on these accounts. Something similar is also faced by India. While the country has 80% of the population that is unbanked, 48% of these bank accounts saw no transaction, reported an Indian publication. In another instance, the government of India paid from its exchequer to encourage people to open bank accounts. Rs5,000 overdraft was made instantly available for persons opening new accounts. People in India rushed to open a bank account and after redeeming overdraft facilities, these bank accounts were never used.

At least in Pakistan, part of the reason there are inactive bank accounts can be rationalised by the prevalence of high charges by banks for using their services that keeps customers from using these services. Part of it can also be blamed on the morbid fascination of Pakistanis with cash that won’t go away. And part of the reason for the fascination is the fear that people have that comes with the pains associated with becoming accountable to authorities after getting documented. Together, this makes cash a better alternative to holding a bank account.

“People would be willing to visit a bank branch and exchange their soiled notes to get newer ones, but they won’t go in to open a bank account. It shows that the society still prefers to use cash,” says Omar Moeen Malik.

But it can’t all be blamed on cash. While the policies have been focused on ease of access, not enough has been done to create use-cases for the low-income groups to prioritise using banking services over payments in cash. That is to say where can the payments be made using a wallet or a bank account. The typical use-cases that are available on mobile apps of banks and wallets are mobile top ups and utilities payments. While these are important use cases, these are not the only ones. For low-income groups, they make frequent and small mostly grocery purchases. But there are no such use-cases that have been enabled on these platforms yet. It is therefore no surprise that people who do not make much in a month, even if they have a bank account, withdraw their entire salary in one or two ATM transactions and use cash for all transactions.

While there are these use-cases that are not available on such applications, there are not enough smartphone users eithers that can use these applications. Majority of the users use feature phones that do not have wallets or banking applications.

An effort was made by the SBP to introduce mobile money accounts called Aasan Mobile Account (AMA) that could be opened with any bank using a feature phone via USSD channels. The leadership of the fintech company that was mandated to start AMA, Virtual Remittance Gateway (VRG), in an earlier interview with Profit, had aspired to make use cases such as micro purchases with a vegetable vendor available for masses on their phones. “In absence of such use-cases, cash becomes priority and then financial inclusion becomes difficult,” says Ali Sarfaraz. “The scope of financial inclusion is massive and it has worked in other countries. But we have a long way to go.”

Why banks are not invested in financial inclusion

“It is true that traditional brick-and-mortar banks have very little seriousness towards financial inclusion,” says Ali. “In Pakistan, the majority of our banks are private banks whereas in India, most of the banks are public entities. We privatised our entire banking sector. Then we said that we should have a few big banks and they should serve all sorts of customers. These banks should be giving money to the government, they should give money to the SMEs, to corporates and they should do personal financing as well,” he adds.

“The idea was that if a bank was large and if it had a large capital base, it would be able to introduce and manage different products that would include some products that would be risky, as well as some products that would be less risky. But banks would be diversifying. Now in theory, it was not a bad idea. And we created big banks. The top few banks have 80% industry assets whereas the remaining have 20% assets,” explains Ali.

“But like everywhere else in the society, we have this elite capture in the banking sector as well [that is hindering financial inclusion,” he says.

And the government is complicit. Most of the deposits of commercial banks go as loans to the government that needs to finance its deficit, leaving only little to be offered to low-income people looking to finance their needs.

“After the government, their priority is to finance entities like PIA and OGDCL, entities that have sovereign guarantees from the government of Pakistan,” explains Ali.

“Banks would finance power plants that also receive payments from the government so it is also a low-risk investment. So really, personal finance takes a back seat when the government becomes the biggest borrower. Right now, if the government deficit reduces, the banks would then find people to lend money to. Then they will give mortgages and personal loans and financial inclusion will increase,” he adds.

And the government is not helping its case either

Here’s where it truly gets absurd: the government has a number of schemes designed to help low-income earners. The only problem is, you need to have an active bank account to qualify for them. These schemes are quite literally designed to alleviate poverty, and haven’t understood the basic underlying problem of financial inclusion.

“If there is a government scheme, like housing schemes like Naya Pakistan Housing Scheme being launched by the government right now and G2P payments like Ehsaas Programme, to participate in that, you need an account. So in many cases, you will not be able to participate because you do not have an account,” says Sakib Sherani, a prominent economist and CEO of Macro Economic Insights, a research house on economics. But all that is yet to bear any fruits for the segments of society that are supposed to be helped by this financial inclusion slogan.

What does the ‘financially included’ get? If that financially included is moneyed, there’s a range of financial services available that are costly (high-interest rates charged by banks on personal loans and credit cards for example). Therefore, only the moneyed would get those services. For the ones that are not that well-off, the incentives for them to actively open and use bank accounts is simply not there. There are only costs of maintaining bank accounts that, being low on income, the underbanked would want to avoid.

Simply opening a bank account gets you nowhere, when there are no incentives to open these bank accounts. Ali also concurs, and as is evident, that as things are structured right now, there is no melody in the financial inclusion ballad for the many that are unbanked.

While there are policies and regulations focused on ease of access, what the policymakers choose to forget is that the majority of the population is not literate generally and for a population that is not literate, financial literacy is understandably low. So no matter how much you boast about policies that improve financial inclusion, if people’s incentives are not aligned or they don’t know about the benefits of having a bank account, how to operate a bank account or a wallet, the whole concept becomes overrated.

The main problem with these electronic money transfer institutions is there source of earning. Currently they are only relying on commission based earning but interest and investment income are two critical components of any financial institutions which to date are missing.