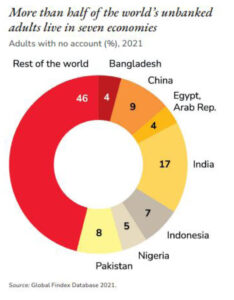

When it comes to financial inclusivity, Pakistan ranks close to the lowest rung of the ladder as a majority of its population has no access to formal financial services, savings, credit, insurance or even the knowledge required to be able to make intelligent pecuniary choices. The country is part of a seven-nation group that is home to more than 50% of the world’s unbanked population. In an agrarian economy, the bulk of the unbanked population is rural farmers.

As per, “The business case for the financial inclusion of rural women” a study by MDF, Kashf Foundation and Khushhali Microfinance Bank (KMBL) in 2020, “Access to finance remains very scarce in rural areas. Smallholder farmers are particularly poorly served: 29 percent are entirely excluded and most of the remainder have only limited access to formal finance. Instead, farmers rely on traders and moneylenders to meet their credit needs, often tied to sale of inputs and with repayments tied to future sales of farmers’ produce. Commercial banks are hesitant or unable to provide financial services to less lucrative rural markets.”

“Villages are too small to justify setting up branches, and State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) regulations prohibit banks from doing business outside a 50km radius of a branch. Some banks (e.g. Habib Bank, Al- Baraka, MCB) use vehicles to offer mobile banking services, but their products remain ill-suited to smallholder clientele due to high minimum loan values and stringent collateral requirements. Providers of microfinance services do target rural farmers, but their coverage remains low, due to high transaction costs and limited human resources.” The report further added.

“Villages are too small to justify setting up branches, and State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) regulations prohibit banks from doing business outside a 50km radius of a branch. Some banks (e.g. Habib Bank, Al- Baraka, MCB) use vehicles to offer mobile banking services, but their products remain ill-suited to smallholder clientele due to high minimum loan values and stringent collateral requirements. Providers of microfinance services do target rural farmers, but their coverage remains low, due to high transaction costs and limited human resources.” The report further added.

However, when one disseminates the data, another concerning trend is highlighted; the deplorable state of female financial inclusion in the country.

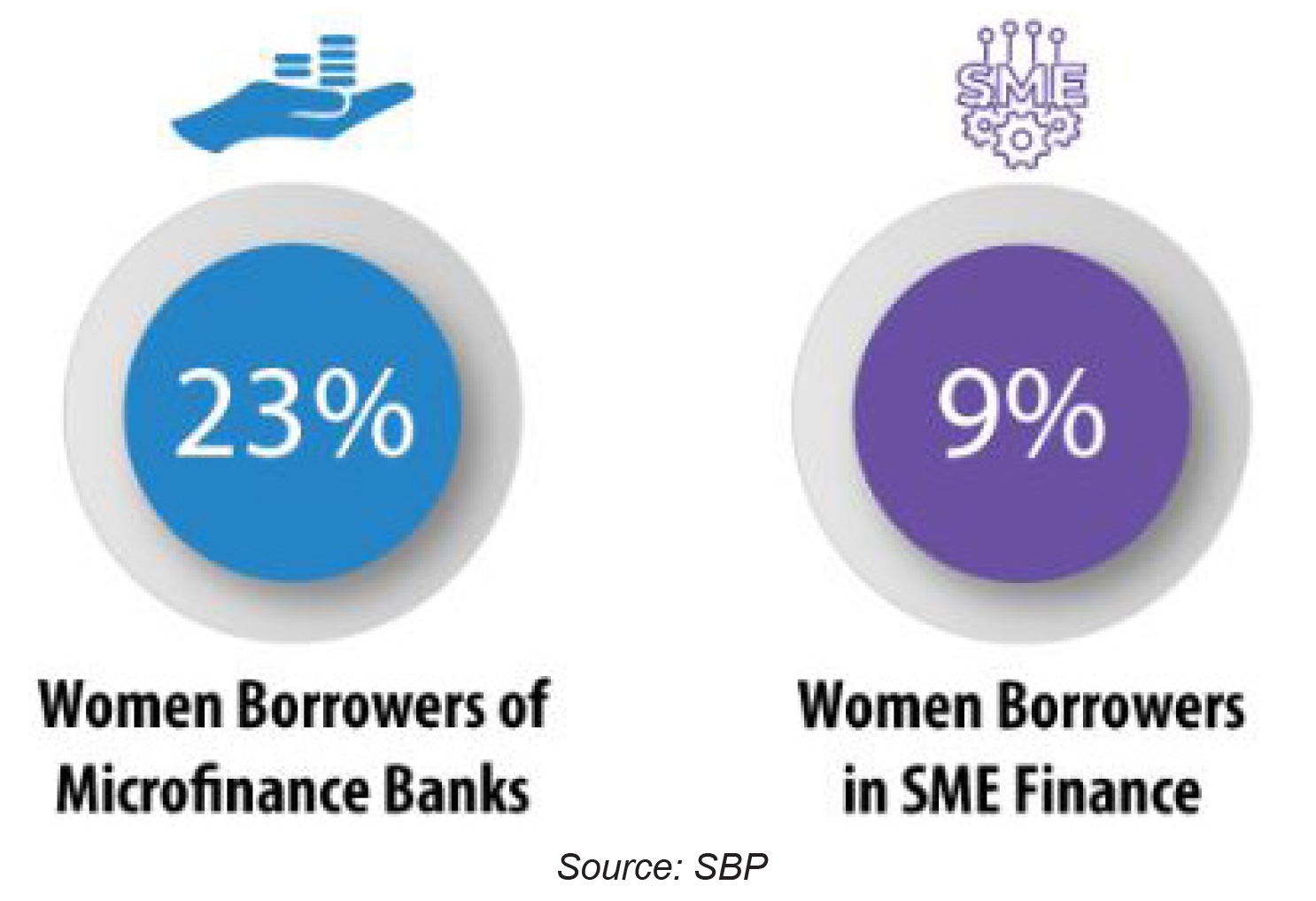

According to the study, “It is estimated that microfinance services currently only serve 11.5 percent of a potential market of 27 million people. Women in Pakistan have even greater barriers in accessing finance. Nationwide only seven percent of women hold a bank account. In 2019, only three percent of SME loans and nineteen percent of microfinance loans were distributed to women.”

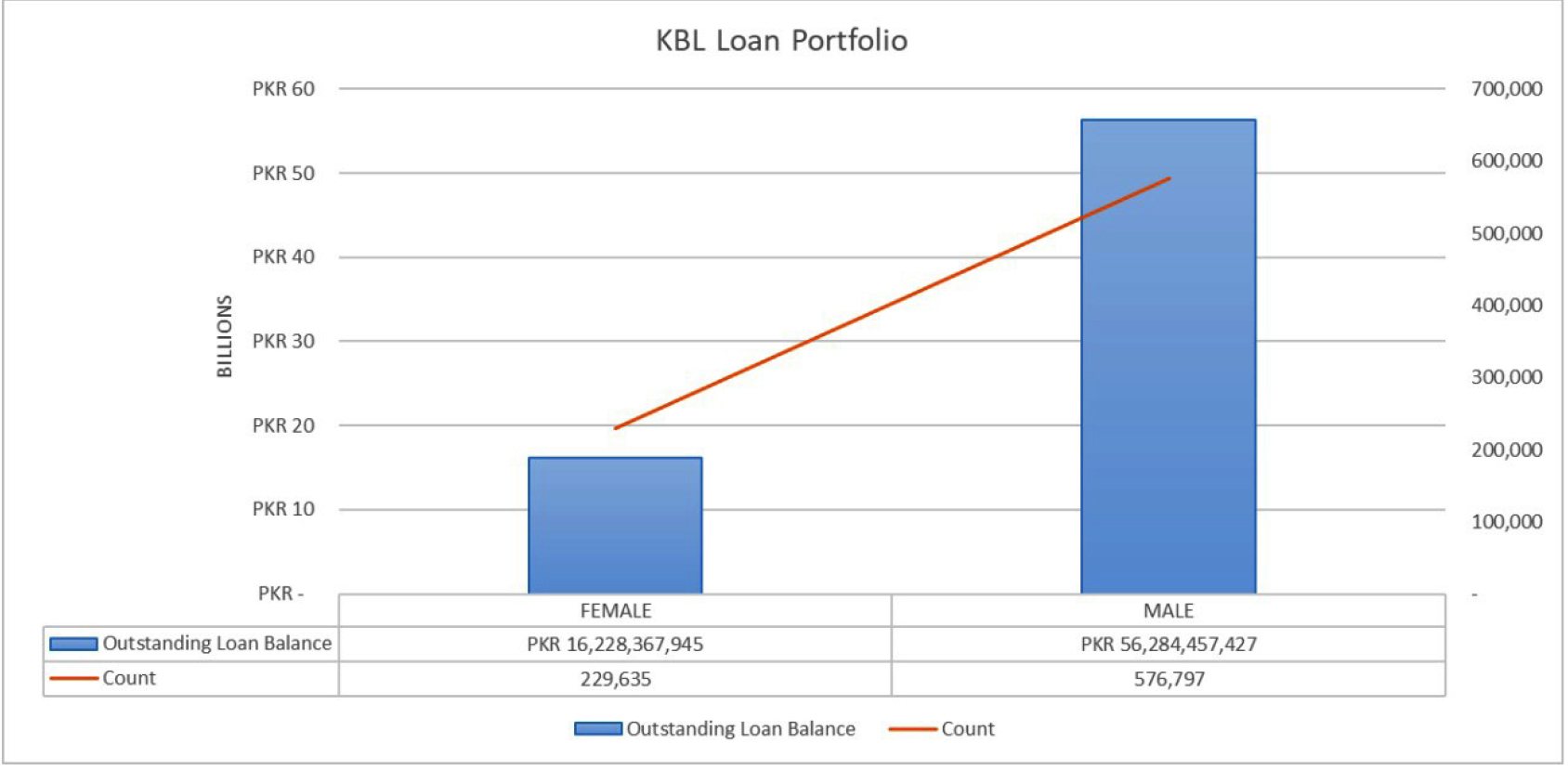

KMBL, the largest Microfinance Bank in the country, had a closing portfolio of around 72 billion in December 2021 out of which only 22% pertained to female lending. The figure is closer to 20-21% for Mobilink Bank, which claims to be the country’s largest digital bank. As per SBP, the industry average figure is around 23%.

Despite the fact that the situation in Pakistan is similar to other medium and low-income countries, it is actually amongst the worst performing when it comes to numbers.

“The majority of unbanked adults continue to be women even in economies that have successfully increased account ownership and have a small share of unbanked adults. In Türkiye, for example, about a quarter of adults are unbanked, and yet 71 percent of those unbanked adults are women. Brazil, China, Kenya, Russia, and Thailand also have relatively high rates of account ownership, compared with their developing economy peers, and yet a majority of those who are still unbanked are women. Things are not much different in economies in which less than half the population is banked. For example, in Egypt, Guinea, and Pakistan women make up more than half of the unbanked population,” says a Findex Report 2021.

Against this backdrop, the continued growth of the gender gap in Pakistan makes the situation unbearably hopeless. Yet another area that highlights this is that of mobile money. As per a GSMA report, State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money 2022, “In Pakistan for instance, 76 percent of men and 51 percent of women own a mobile phone, 77 percent of men and 70 percent of women have heard of at least one national brand of mobile money, but only 19 percent of men and six per cent of women have a mobile money account.”

The figures are representative of the overall gender disparity in Pakistan. As per the Global Gender Gap Report 2021 by the World Economic Forum, Pakistan ranks 153 out of 156 countries when benchmarked against the criteria of Economic Participation and Opportunity, Educational Attainment, Health and Survival, and Political Empowerment.

Underlying Factors

These figures routinely make one wonder about what lies behind the lack of inclusivity in finance for women. And the list of reasons is as long as it is frustrating. The ones doing the most damage include long-standing structural flaws, societal norms and an unwillingness on the institutional front to turn the tide.

As per the Findex report 2021, “Women are often excluded from formal banking services because they lack official forms of identification, do not own a mobile phone or other forms of technology, and have lower financial capability.”

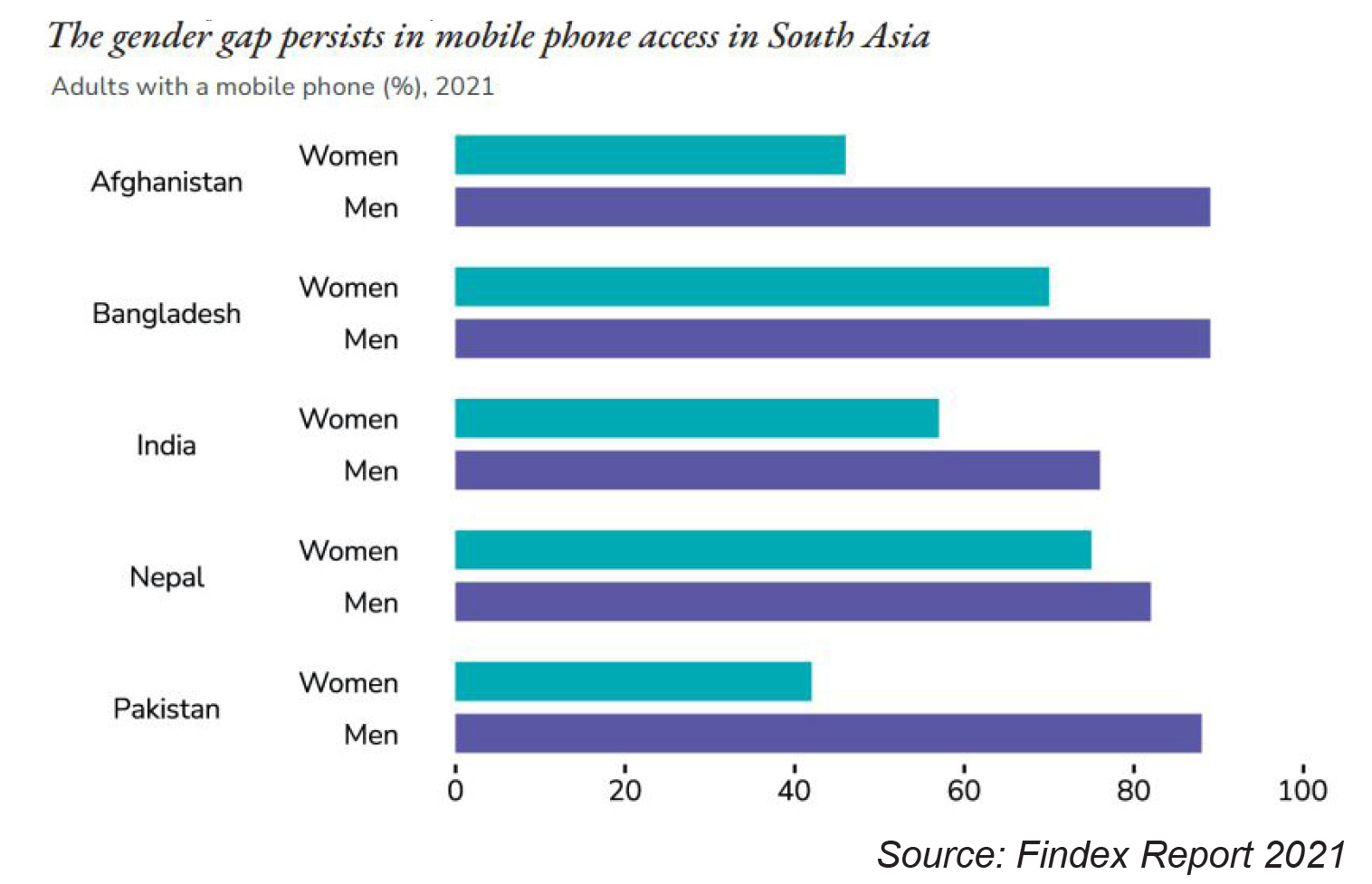

“In South Asia, for example, women are 22 percentage points less likely than men to have a mobile phone. India and Bangladesh are near the South Asian average, with gaps in mobile ownership of 19 and 20 percentage points, respectively. In Pakistan, women are half as likely as men to have a mobile phone.” The report further added.

Furthermore, the loan disbursement figures to the female population might be exaggerated due to the fact that these women might just be the face of the borrowing process and not the ultimate beneficiary.

“Some evidence suggests that women are often not the final users of loans, but rather are conduits to male household members. The report documents findings that suggest that the practice of passing on loans to male household members is potentially quite widespread; women may be bearing all the transaction costs and risks of accessing loans, but are not the final beneficiaries,” finds a report titled, Are Pakistan’s Women Entrepreneurs Being Served by the Microfinance Sector? A World Bank study.

But perhaps, the most determining role in sustaining and perpetuating gender inequity decade after decade is played by social structures. Deeply-rooted human bias and the inability to fight social and familial hierarchy especially prevalent in the rural areas do not allow female participation in the financial system.

As per, Financial Inclusion in Pakistan, the business case for the financial inclusion of rural women, a study by MDF in 2020, “Women depend on their parents and husbands for income and lack avenues for savings, except for dowries for their daughters. In agricultural households, even though women often care for livestock, they are not involved in transactions — the purchase or sale of inputs, animals or milk, or engagement with extension officers. In the rare instances where women obtain credit they have insufficient knowledge to manage it.”

At the service provider level, there is a bias when lending to the female segment as they are asked to bring in a male guarantor or the loan staff, primarily men, are more comfortable dealing with male borrowers. However, there is not just human bias.

“A study from Pakistan of 5,500 digital loan applications compared outcomes of submissions randomly assigned for review by loan officers or by a machine learning algorithm. The study found that the algorithm achieved a 21 percent reduction in loan defaults while serving a similar share of female and ethnic minority group borrowers. However, when the gender of the applicants was revealed in the data, loan officers exhibited a positive bias, approving 22 percent more applications from women than those based on an anonymised review, without leading to an increase in defaults. When the algorithm was exposed to gender information, it was better able to predict defaults than loan officers, but it approved 16 – 21 percent fewer applications from women than when it was fed anonymized data.” Finance for Equitable Recovery, A World Bank report published in 2022.

“In the case of productive lending, lack of documents and awareness is the primary impediment. On the digital front, we experienced that women could not open accounts as the vetting process failed because they were using SIMs that were not registered in their own name.” Sardar Abubakr, the Chief Finance and Digital officer of Mobilink Bank, told Profit.

Breaking the Bias

The situation calls for remedial action to be taken immediately and the starting point has to be at the policy framework level. For the longest time, there was no dedicated framework for financial inclusion of women. However, recently, the SBP launched the Banking on Equality policy that provides the roadmap for the aforementioned.

The policy targets, “Increase women’s ratio in the financial sector to 20%, Increase ratio of women, branchless banking agents, to 10%, Increase outreach of women-centric products & services, access and usage of accounts, and financing to women entrepreneurs to reach 20 million unique active digital accounts for women by 2023, Place Women Champions at 75% of all bank touch points and Impart gender sensitivity training to all staff members to improve elimination of implicit gender biases.”

Compulsory gender sensitivity training for the customer-facing staff of financial institutions seems like the need of the hour but outreach cannot be extended without employing more women in the sales staff. At the product level, dedicated tailored solutions for female clientele are necessary and a requirement under SBPs new policy.

“We need to understand the customer persona so products and partnerships can be developed accordingly. For instance, MMBL has recently entered into a partnership with Foodpanda

to provide bridge financing to thousands of home chefs (around 60% women). The advantage of such collaboration is the data sharing that allows us to complete our due diligence without bothering the consumer,” says Abubakr.

Investing in female financial inclusion can yield great dividends and the Grameen Bank model of Bangladesh vouches for it. The bank initiated the disbursement of microcredit to rural women and led to a surge in female entrepreneurship which had a multiplier effect on the country’s economy. Pakistan can learn from its former territory and take a step towards the right direction.

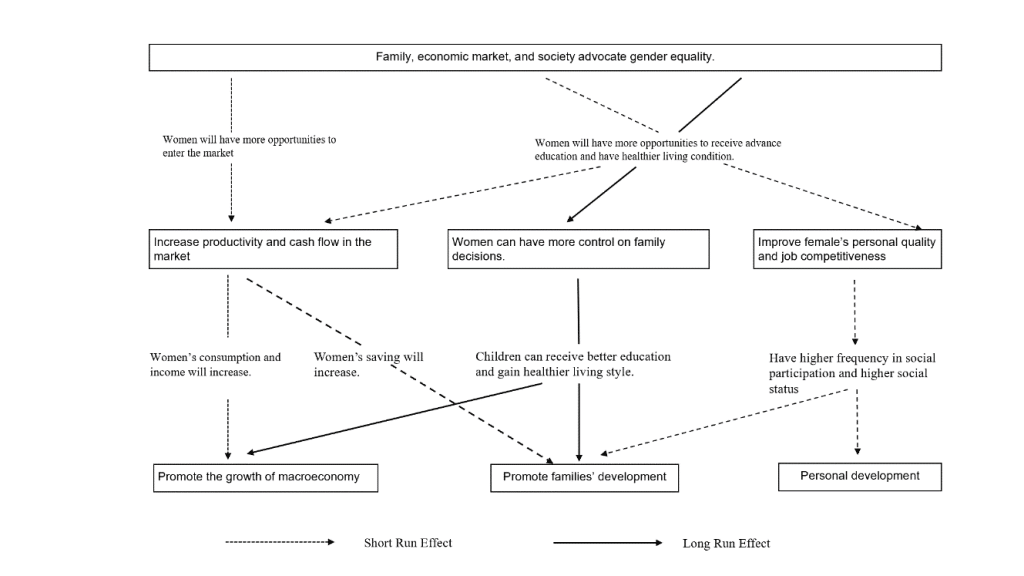

Gender Dividend Framework (Source: Shi & Zhang, 2020)

Reward yourself with our appealing Bath towel Sets in Pakistan. Our Hand Towel in Pakistan are manufactured to the highest standard from start to finish. Shop Online!

Our Driver Gloves are a great addition to your outfit, so the next time you take your automobile out for a spin, don’t forget to wear them.

AUA is one of the best Caribbean Medical University to study medicine with its accredited programs.

We are the Best Family Lawyer in Karachi. Contact us Today for all your Child Custody, Adoption & Divorce related matters in Pakistan

I’m truly impressed with your blog article, such extraordinary and valuable data you referenced here.

사설 카지노

j9korea.com